1 Audioguide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spore Strips, Crushable S

303-987-8000 or 800-992-6372 [email protected] Regulatory officials and sterilization experts have voiced concerns regarding the appropriateness of using a Biological Indicator (BI) Ampoule interchangeably with spore strips or other approved self-contained Biological Indicators (BIs). They argued spores in a sealed glass ampoule do not have direct contact with the steam, and this lack of direct contact with the sterilant caused the Ampoule to behave differently than other types of BIs. There was no scientific data to support this argument, only the belief that since the spores do not have direct contact with the steam, the Ampoule should not be used in porous load cycles because a “poor quality steam environment” might not be detected by the Ampoule. This argument disregards the fact that the Ampoule BIs are tested for population, Dvalue and Zvalue by the same standardized methods and equipment that are used to test other BIs. The following report will describe various tests and data collected to determine if the Ampoule BI behaves equivalently to spore strips and other self-contained BIs. Background: Biological Indicators (BIs) are used to determine whether a sterilizer has delivered a lethal cycle. Evaluation of resistant, spore-forming microorganisms processed through steam cycles gives the operator a direct measurement of the lethality delivered by the sterilizer during that particular cycle. The organisms used are of known quantity (population) and resistance (Dvalue). The organisms are packaged in such a way as to allow the sterilant access to the spores, and allow for either enumeration or recovery of surviving organisms. -

Simultaneous Determination of Arsenic, Manganese and Selenium in Human Serum by Neutron Activation Analysis

View metadata,Downloaded citation and from similar orbit.dtu.dk papers on:at core.ac.uk Dec 20, 2017 brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research Database In Technology Simultaneous determination of arsenic, manganese and selenium in human serum by neutron activation analysis Damsgaard, E.; Heydorn, Kaj; Larsen, N.A.; Nielsen, B. Publication date: 1973 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Damsgaard, E., Heydorn, K., Larsen, N. A., & Nielsen, B. (1973). Simultaneous determination of arsenic, manganese and selenium in human serum by neutron activation analysis. (Denmark. Forskningscenter Risoe. Risoe-R; No. 271). General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Risø Report No. 271 O Z 8o* Danish Atomic Energy Commission Bh Research Establishment Risø Simultaneous Determination of Arsenic, Manganese and Selenium in Human Serum by Neutron Activation Analysis by E. -

0M Mm EC Vc WM W

APII'I'l 25, 1972 P. w. MCCONNAUGHEY 3,658,719 SMOKE GENE-RATING TUBE Filed Oct. 9, 1969 \\\\\\\\\\~\ NJmyj \\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\~\\\\\\\\\\\~Y \ R v.a la W. WMVc EC mm 0m (like), 1/17/; // - 1/ 1 .. 3,658,719 United States Patent 0 1C€ Patented Apr. 25, 1972 1 2 a perforated envelope 6 of polyethylene tubing heat 3,658,719 sealed at one end 8 and folded over at the other end 10. SMOKE GENERATING TUBE Paul W. McConnaughey, Wilkinsburg, Pa., assignor to As best seen in FIG. 2, the envelope has a plurality of Mine Safety Appliances Company, Pittsburgh, Pa. perforations 12 made as by cutting slits in the tubing Filed Oct. 9, 1969, Ser. No. 865,039 Wall. The perforations provide only small dimension Int. Cl. B01d; B01f; B01j 13/00 openings so that transfer of the volatile acid portion of US. Cl. 252—-359 A 2 Claims the reagent is substantially by diffusion; that is, there is no signi?cant convection ?ow of gases through the en velope. A great variety of methods of making suitable ABSTRACT OF THE DISCLOSURE 10 perforations are well known, such as, for example, slit ting or puncturing with needles or electrical sparks. Base A solid acid reagent and a solid base reagent are sepa reagent 14 is likewise contained in a breakable ampoule rately contained in a breakable ampoule that is enclosed 16 enclosed in perforated envelope 20. Both envelopes in a perforated envelope, which is in turn contained in are contained in a pliable tube 22 with suitable porous a pliable tube. -

Submission of Evidence Guidelines-101508-Print

GUIDELINES FOR THE COLLECTION AND SUBMISSION OF FORENSIC EVIDENCE Delaware Department of Health and Social Services Office of the Chief Medical Examiner Forensic Sciences Laboratory 200 South Adams St., Wilmington, DE 19801 (302)-577-3420 © Copyright 2008 Richard T. Callery, M.D., F.C.A.P. , Chief Medical Examiner and Director of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner Forensic Sciences Laboratory Mission Statement The OCME evidentiary guidelines are dedicated to all past, present, and future public servants who dedicate their careers to providing the state of Delaware with the highest degree of law enforcement, forensic science, and medical-legal death investigation services while maintaining the traditions of fairness, professionalism, and integrity. Delaware OCME - Forensic Sciences Laboratory Evidence Submission Guidelines 2008 Rev (0).pub — Page 3 — TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction············································································································ 7 Using the Laboratory in the Judicial Process···························································· 8 Crime Scene Processing························································································· 9 General Submission Instructions ·······································································11-15 General Information·························································································· 11 Choosing Containers ························································································ -

WSU SURCA Poster Event Leads to 51 Awards to 57 Undergraduate Researchers

March 27, 2017 SURCA.WSU.EDU SURCA is hosted by the Office of Undergraduate Research part of WSU Undergraduate Education. TABLE OF CONTENTS Schedule of Events .................................................................... 2 SURCA 2017 Committee .......................................................... 3 Judges (alphabetical listing) ...................................................... 4 Judges (external organizations) ................................................ 5 Judging Rubric .......................................................................... 6 Sponsors .................................................................................... 7 Award Winners (news article) ................................................... 8 Entries (presenters in alphabetical order) ............................... 12 Abstracts (numerically by presentation number) .................. 34 1 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Monday, March 27, 2017 Posters: M.G. Carey Senior Ballroom, Compton Union Building (CUB) Awards: CUB Auditorium (Room 177) Noon – 2 p.m. Student presenters hang their own posters 2:00 - 2:45 p.m. Informal judging (no students present) 2:45 – 3:45 p.m. Formal judging (only judges and presenters in room until 3:30 p.m.) 3:30 – 5:00 p.m. Public viewing 5:00 – 5:45 p.m. SURCA Awards Ceremony (all welcome to attend) 5:45 p.m. Presenters remove posters and pick up judges’ feedback sheets 2 COMMITTEE Talea Anderson WSU Libraries Lydia Gerber College of Arts and Sciences Samantha Gizerian College of Veterinary Medicine Kaitlin Hennessy Global -

VSMOW Triple Point of Water Cells: Borosilicate Versus Fused-Quartz

VSMOW Triple Point of Water Cells: Borosilicate versus Fused- Quartz M. Zhao1,3 and G. F. Strouse 2 1 Fluke Corporation, Hart Scientific Division, American Fork, Utah 84003, U.S.A. 2 National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899, U.S.A. 3 To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT To investigate an ideal container material for the triple point of water (TPW) cell, and reduce the influence to the triple-point temperature due to the deviation of the isotopic composition of the water, we developed and tested both borosilicate and fused-quartz glass shelled TPW cells with isotopic composition substantially matching that of Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW). Through a specially designed manufacturing system, the isotopic composition, δD and δ18O, of the water in the TPW cell could be controlled within ±10‰ (per mil) and ±1.5‰ respectively, resulting in control of the isotopic temperature correction to better than ±8 µK. Through an ampoule attached to the cell, the isotopic composition of the water in the cell could be analyzed individually. After manufacture, the initial triple-point temperature of the two types of cell were measured and compared to assess the quality of the cells and manufacturing process. Cells fabricated with the new system agree to within 50 µK. Two innovatively-designed borosilicate and fused-quartz TPW cells were made, each with six attached ampoules. We removed one ampoule every six months to track any changes in purity of the water over time. KEY WORDS: isotopic composition; ITS-90, TPW cell; Vienna standard mean ocean water; VSMOW; water impurities; water triple point. -

Accessories for Differential Scanning Calorimeters and Thermobalances

Analyzing & Testing Accessories for Differential Scanning Calorimeters and Thermobalances Crucibles, Sensors, Sample Carriers, Calibration Kits for DSC, TGA and STA Systems Introduction – Table of Contents Accessories for Thermal Analysis – DSC/DTA, TGA and STA Thermal analysis is a powerful, well and instrument parts must be prevented meshes and baskets are available proven tool for obtaining reliable data while ensuring that the test results to accommodate specific sample on the caloric and thermophysical remain reliable and accurate. For these dimensions and densities. properties of a great variety of materials. reasons, one of our primary areas of focus is crucibles and sensors for DTA/ Lately, the demand for special crucibles To attain proper results, proficient DSC, TGA and STA instruments. has been increasing. Of course, state-of-the-art instruments are measurements can only be carried out required, featuring optimum technical This catalogue provides an overview of when the right sensor or sample carrier attributes such as high sensitivity and all such crucibles and sensors for DTA, for these special crucibles is available. resolution in the required temperature DSC, TGA and STA measurements. We have therefore listed these special range. In recent years, a rise in the You will find many different crucible cases here, often providing application development of new materials for materials listed, and a variety of types examples to demonstrate their emerging applications has been and special shapes. From among these, characteristic advantages. presenting an ongoing challenge for we can help you find the right crucible the thermal analysis industry in keeping size and material for any application, Our accessories can open up a world pace with rapidly evolving market be it standard or special. -

Production Line and Machines Automatic Tablet Press Production

Production Line and Machines Automatic Tablet Press Production Line Auto Coater Machines and Manuel Coating Machine Automatic Packaging Machines Full Automatic Filling Hard Capsule Production Line Full Automatic Filling Soft Gelatin Capsule Production Line Full Automatic Ampule Production Line Full Automatic Liqued Vial Production Line Full Automatic Powder Vial Production Line Full Automatic Liquid Syrup Production Line Full Automatic Dry Syrup Production Line Full Automatic Ointment Production Line Full Automatic Nasal Spray Filling Machine Full Automatic suppository Production Line Full Automatic I.V. Solution System Full Automatic Non-PVC Soft Bag IV Solution Production Line Full Automatic PP bottle IV solution production line Air Flow Drier AL-Plastic-AL Automatic Blister Packing Machine Aluminum Foil Ampoule Cleaning Machine Ampoule Compact Line Ampoule Filler Ampoule Filling and Sealing Machine Ampoule Filling Sealing Machine Ampoule Labeling Machine Ampoule Production Line Ampoule Sealing Machine Ampoule Sesler Ampoule Washer Ampoule Washing Machine Ampoule Washing, Drying and Filling Production Line Antibiotic Vial Washing Machine Aseptic Liquid Filling Machine Atuomatic Blister Packing Machine Atuomatic Liquid Vial Filling Machine Auto-Checking Forming Blister Packing Machine Automatic Air Jet Cleaning Machine Automatic Airjet & Vacuum Cleaning Machine Automatic Ampoule Filling & Sealing Machines Automatic Ampoule Inspection Machine Automatic Ampoule Screen Printing Machine Automatic Ampoule Sticker Labeling Machine Automatic -

Analytical Methods and Procedures in the Small Winery Laboratory

Appendix A Analytical Methods and Procedures in the Small Winery Laboratory 1. Acetaldehyde Determination 2. Agar Slant Preparation 3. Alcohol Determination by Distillation 4. Alcohol Determination by Salleron-DuJardin Ebulliometer 5. Balling Determination 6. Brix Determination by Hydrometer '7. Brix Determination by Refractometer 8. Carbon Dioxide Determination by Piercing Device 9. Copper and Iron Determination by Spectrophotometry 10. Differential Stain Procedure 11. Extract Determination by Hydrometer 12. Extract Determination by Nomograph-Dessert Wines 13. Extract Determination by Nomograph-Table Wines 14. Gram Stain Procedure 15. Light Transmission (Color Intensity) by Spectrophotometry 16. Malo-Lactic Fermentation Determination by Paper Chromatography 17. Microscopy 18. Organoleptic Analysis 19. Oxygen Determination 20. pH Determination 21. Plating Procedure 22. Sulfur Dioxide-Free 23. Sulfur Dioxide-Total 24. Total Acidity Determination by Titration 25. Total Acidity Determination by Titration-pH Meter 26. Viable Microorganisms in Bottled Wines-Millipore Method 27. Viable Yeasts in Bottled Wines-Rapid Method of Detection 28. Volatile Acidity Determination by Cash Volatile Acid Apparatus Courtesy of Champagne News and Information Bureau 311 312 COMMERCIAL WINEMAKING 1. ACETALDEHYDE DETERMINATION When analyzing wines for total acetaldehyde content, a small percentage (3-4% in wines containing 20% ethanol and less than 1% in table wine containing 12% ethanol) is bound as acetal. This is not recovered in the usual procedures. The procedure given below is that of Jaulmes and Ham elle as tested by Guymon and Wright and is an official method of the AOAC. Modifications to consider the acetal concentration can be made. The air oxidative changes taking place during the alkaline titration step are pre vented by addition of a chelating agent (EDTA) to bind copper present. -

Polymer Chemistry

Polymer Chemistry View Article Online PAPER View Journal | View Issue Mono- and dimeric zinc(II) complexes for PLA production and degradation into methyl lactate – Cite this: Polym. Chem., 2020, 11, 2381 a chemical recycling method† Jack Payne,a Paul McKeown,a Mary F. Mahon,b Emma A. C. Emanuelssona,c and Matthew D. Jones *a,b A series of well-defined mono- and dimeric Zn(II)-complexes were prepared and fully characterised by X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. Their application to the ROP of rac-LA to produce biocom- patible atactic PLA was demonstrated in both solution and under industrially preferred melt conditions at 180 °C with a [rac-LA] : [Init] : [BnOH] of 3000 : 1 : 10. Exceptional activity was observed in all instances, albeit with generally poor molecular weight control (Mn) and broad dispersities (Đ), with dimers outper- forming their monomeric counterparts. The propensity of all Zn(II)-complexes to facilitate PLA degra- Received 5th February 2020, dation into methyl lactate (Me-LA) under mild conditions is also demonstrated. Zn(2–3)2 were identified Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. Accepted 25th February 2020 as the outstanding candidates, achieving full conversion to Me-LA within 8 h at 80 °C in THF. Further DOI: 10.1039/d0py00192a −1 degradation kinetic analysis revealed Zn(2–3)2 to have kapp values of 0.63 ± 0.051 and 0.44 ± 0.029 h rsc.li/polymers for the rate of consumption of PLA respectively. Introduction ing alternative to traditional polymers since they can be pro- duced from biomass, which remains a relatively untapped, Petroleum-based polymers (plastics) dominate modern-day abundant resource.3 Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), a sustainable and This article is licensed under a society, with annual global production exceeding 300 biocompatible aliphatic polyester, has emerged as one of the Mtonnes, of which ca. -

Package Codes

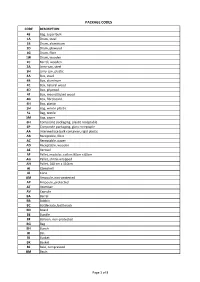

PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION 43 Bag, super bulk 1A Drum, steel 1B Drum, aluminium 1D Drum, plywood 1G Drum, fibre 1W Drum, wooden 2C Barrel, wooden 3A Jerry-can, steel 3H Jerry-can, plastic 4A Box, steel 4B Box, aluminum 4C Box, natural wood 4D Box, plywood 4F Box, reconstituted wood 4G Box, fibreboard 4H Box, plastic 5H Bag, woven plastic 5L Bag, textile 5M Bag, paper 6H ComposIte packaging, plastic receptable 6P Composite packaging, glass receptaple AA Intermediate bulk container, rigid plastic AB Receptable, fibre AC Receptable, paper AD Receptable, wooden AE Aerosol AF Pallet, modular, collars 80cm x 60cm AG Pallet, shrink-wrapped AH Pallet, 100 cm x 110cm AI Clamshell AJ Cone AM Ampoule, non-protected AP Ampoule, protected AT Atomiser AV Capsule BA Barrel BB Bobbin BC Bottlecrate, bottlerack BD Board BE Bundle BF Balloon, non-protected BG Bag BH Bunch BI Bin BJ Bucket BK Basket BL Bale, compressed BM Basin Page 1 of 8 PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION BN Bale, non-compressed BO Bottle, non-protected, cylindrical BP Balloon, protected BQ Bottle, protected cylindrical BR Bar BS Bottle, non-protected, bulbous BT Bolt BU Butt BV Bottle, protected bulbous BW Box, for liquids BX Box BY Board, in bundle/bunch/truss, BZ Bars, in bundle/bunch/truss CA Can, rectangular CB Beer crate CC Churn CD Can, with handle and spout CE Creel CF Coffer CG Cage CH Chest CI Canister CJ Coffin CK Cask CL Coil CM Collis CN Container not otherwise specified as transport equipment CO Carboy, non-protected CP Carboy, protected CQ Cartdidge CR Crate CS Case CT -

Units of Measure Used in International Trade Page 1/57 Annex II (Informative) Units of Measure: Code Elements Listed by Name

Annex II (Informative) Units of Measure: Code elements listed by name The table column titled “Level/Category” identifies the normative or informative relevance of the unit: level 1 – normative = SI normative units, standard and commonly used multiples level 2 – normative equivalent = SI normative equivalent units (UK, US, etc.) and commonly used multiples level 3 – informative = Units of count and other units of measure (invariably with no comprehensive conversion factor to SI) The code elements for units of packaging are specified in UN/ECE Recommendation No. 21 (Codes for types of cargo, packages and packaging materials). See note at the end of this Annex). ST Name Level/ Representation symbol Conversion factor to SI Common Description Category Code D 15 °C calorie 2 cal₁₅ 4,185 5 J A1 + 8-part cloud cover 3.9 A59 A unit of count defining the number of eighth-parts as a measure of the celestial dome cloud coverage. | access line 3.5 AL A unit of count defining the number of telephone access lines. acre 2 acre 4 046,856 m² ACR + active unit 3.9 E25 A unit of count defining the number of active units within a substance. + activity 3.2 ACT A unit of count defining the number of activities (activity: a unit of work or action). X actual ton 3.1 26 | additional minute 3.5 AH A unit of time defining the number of minutes in addition to the referenced minutes. | air dry metric ton 3.1 MD A unit of count defining the number of metric tons of a product, disregarding the water content of the product.