Erickson, Paul R. Passports to Paradise: the Stru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOOD SUNDAYS CAN CHANGE YOUR ETERNITY This Week I Was

GOOD SUNDAYS CAN CHANGE YOUR ETERNITY This week I was at a conference and heard a Pastor named Mark Hughes from Church on the Rock in Winnipeg tell this story. He and his wife love Kayaking. This past summer they decided to go to Lake of the Woods and Kayak around the Sable Islands in the south of the lake. For Kayakers, that is paradise. The problem is that there are no roads that get you close to them. He saw a road on Google Earth that he figured would be the best route. They set off, kayaks on the roof of their car dressed in beach clothes. After driving down endless gravel roads he came to a gate. There were a number of men standing around drinking coffee and smoking. He waved to them and no one said anything so he kept going. The road was in bad shape so they had to drive slow. After a long time the road ended at the bottom of a gravel pit. He managed to turn the car around and go back the way they came. Eventually they arrived back at the gate. He rolled down the window and asked one of the workmen how to get to the Sable Islands. The workman said “you have to go back to the main road and then head 4 kms west and then take that road to the end. This road only goes to the gravel pit.” What a great description of so many in this world today. They are looking for paradise but wind up in the pit. -

Happy New Year January 2013/Volume 20 Issue 1 Contributors EDITORS Message from Your Editors

CAT - TALES SM HAPPY NEW YEAR January 2013/Volume 20 Issue 1 CONTRIBUTORS EDITORS Message from your editors: Barbara Voss It’s a new year and another 12 issues of Cat- Jim Alleborn Tales to look forward to. Bill and I weren’t St. Bill Voss James residents when Cat-Tales was started Jim Carey [email protected] so many years ago, but we’ve heard it was a Vicki Caruso page or two on mimeographed paper. Thank PUBLISHED BY you to those folks who started something we Gordon Corlew can all be proud of. This is OUR magazine Melody Bellamy and we should all be proud of it. The articles Mary Ann Derks Coastal Printing & Graphics about neighbors giving their time and money Kathy Fitzgerald to benefit others, sharing life and travel ASSOCIATE EDITORS experiences, and giving us tips for our safety Don Hill and well-being (wine is very important for Bill Allen that!) are things we enjoy each month. Tricia Hill Susan Edwards We wish you health and happiness for the new Carol Kidd Betty Lewis year and are hoping to hear from you with any ideas you may have to make this publication Mike Kirsche Paul Maguire even better. Sue Maguire Barbara Lemos Wendy Taylor Nate Lipsen IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS Phillip Midgett POA Fire, Rescue or Medical Emergency 911 COMMUNICATIONS (Direct Number for 911 Dispatch) 910-253-7490 John Muuss CHAIR St. James Security-Main Gate 910-253-7177 St. James Security-Main Gate 910-253-7178 Kevin O’Connor Lisa Williamson St. James Town Office 910-253-4730 St. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

La Canción De La Semana (13 Al 17 De Noviembre De 2017)

La canción de la semana (13 al 17 de noviembre de 2017) "Deja que te bese” Autor: Alejandro Sanz Alejandro Sánchez Pizarro, más conocido por su nombre artístico Alejandro Sanz (Madrid, 18 de diciembre de 1968), es un cantautor, guitarrista, compositor y músico español. Ha vendido más de 25 millones de copias de sus discos en todo el mundo y ha ganado 20 Grammys Latinos y 3 Grammys americanos. Asimismo, ha realizado colaboraciones con diversos artistas nacionales e internacionales convirtiéndole en uno de los artistas más importantes de la historia de España. Iniciando su impresionante carrera en 1989 con el álbum Los chulos son pa' cuidarlos con el nombre artístico de Alejandro Magno. En 1991 lanzó su segundo álbum —y primero oficialmente como Alejando Sanz— titulado Viviendo deprisa. Alejandro Sanz ha experimentado, buscado y acomodado diferentes estilos. En Si tú me miras y 3, Sanz mostraba su madurez compositiva, pero no fue hasta 1997 con la publicación de Más que incluía singles como Y, ¿si fuera ella?, Corazón partío o Amiga mía cuando Alejandro Sanz se convirtió en leyenda de la música en español, siendo este disco el más vendido en la historia de España y uno de los imprescindibles en lengua hispana. Siendo ya una figura consolidada dio el paso definitivo hacia el mercado americano, El alma al aire dejaba entrever ese cambio de sonidos flamencos, latinos y rockeros confirmados en No es lo mismo y El tren de los momentos . En 2009 salió a la venta Paraíso Express, que incluía el exitoso dueto con la artista norteamericana Alicia Keys llamado Looking for Paradise . -

Xerox University Microfilms 900 North Zaab Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 49100 Ll I!

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good (mage of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 01/10/2019 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 01/10/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Crazy - Patsy Cline Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Let It Go - Idina Menzel Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Perfect - Ed Sheeran Santeria - Sublime Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Girl Crush - Little Big Town Wannabe - Spice Girls Don't Stop Believing - Journey Tequila - The Champs Your Man - Josh Turner Truth Hurts - Lizzo EXPLICIT Dancing Queen - ABBA Turn The Page - Bob Seger Old Town Road (remix) - Lil Nas X EXPLICIT My Girl - The Temptations Always Remember Us This Way - A Star is Born Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Old Town Road - Lil Nas X Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Zombie - The Cranberries House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Creep - Radiohead EXPLICIT Beautiful Crazy - Luke Combs Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Dreams - Fleetwood Mac All Of Me - John Legend My Way - Frank Sinatra Black Velvet - Alannah Myles These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Jackson - Johnny Cash Your Song - Elton John Señorita - Shawn Mendes Baby Shark - Pinkfong Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Valerie - Amy Winehouse Jolene - Dolly Parton EXPLICIT -

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In Love Beyonce BoomBoom Pow Black Eyed Peas Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Old Time Rock n Roll Bob Seger Forever Chris Brown All I do is win DJ Keo Im shipping up to Boston Dropkick Murphy Now that we found love Heavy D and the Boyz Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande and Nicki Manaj Let's get loud J Lo Celebration Kool and the gang Turn Down For What Lil Jon I'm Sexy & I Know It LMFAO Party rock anthem LMFAO Sugar Maroon 5 Animals Martin Garrix Stolen Dance Micky Chance Say Hey (I Love You) Michael Franti and Spearhead Lean On Major Lazer & DJ Snake This will be (an everlasting love) Natalie Cole OMI Cheerleader (Felix Jaehn Remix) Usher OMG Good Life One Republic Tonight is the night OUTASIGHT Don't Stop The Party Pitbull & TJR Time of Our Lives Pitbull and Ne-Yo Get The Party Started Pink Never Gonna give you up Rick Astley Watch Me Silento We Are Family Sister Sledge Bring Em Out T.I. I gotta feeling The Black Eyed Peas Glad you Came The Wanted Beautiful day U2 Viva la vida Coldplay Friends in low places Garth Brooks One more time Daft Punk We found Love Rihanna Where have you been Rihanna Let's go Calvin Harris ft Ne-yo Shut Up And Dance Walk The Moon Blame Calvin Harris Feat John Newman Rather Be Clean Bandit Feat Jess Glynne All About That Bass Megan Trainor Dear Future Husband Megan Trainor Happy Pharrel Williams Can't Feel My Face The Weeknd Work Rihanna My House Flo-Rida Adventure Of A Lifetime Coldplay Cake By The Ocean DNCE Real Love Clean Bandit & Jess Glynne Be Right There Diplo & Sleepy Tom Where Are You Now Justin Bieber & Jack Ü Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun Renegades X Ambassadors Hotline Bling Drake Summer Calvin Harris Feel So Close Calvin Harris Love Never Felt So Good Michael Jackson & Justin Timberlake Counting Stars One Republic Can’t Hold Us Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Ft. -

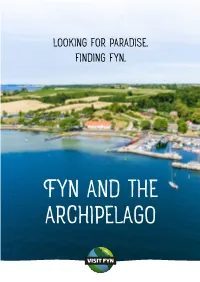

Looking for Paradise. Finding Fyn

LOOKING FOR PARADISE. FINDING FYN. FYN AND THE ARCHIPELAGO The Little Belt YOUR ROUTE Bridge MIDDELFART E2 0 TO FYN HI GH WAY Find further information on the island Fyn and the surrounding islands of the archipelago on visitfyn.com ASSENS FACTS ABOUT FYN AND Like us on Facebook. THE ARCHIPELAGO /visitfyn Number of inhabitants: 488.384 Overall area: 3.489 km2 Number of islands: Over 90 islands, 25 that are inhabited Coastal route: 1.130 km Signposted bike routes: 1.000 km Fishing spots: 117 (seatrout.dk) Harbours: 37 Castles and mansions: 123 Biggest town: Odense – 197.513 inhabitants Geographic position: 96 km away from Legoland Billund, about 1 h drive DENMARK 138 km distance to Copenhagen, about 1:15 h drive 298 km distance to Hamburg, about 3 h drive Travel time: Attractive for families as well as for couples during all seasons. Annually about 1 million visitors FYN FLENSBURG BOGENSE KERTEMINDE E2 0 H ODENSE IGH WAY FYN NYBORG The Great Belt Bridge ASSENS H I G H W A Y LOCAL TOURIST INFORMATION FAABORG VisitAssens Visit Faaborg visitassensinfo.com visitfaaborg.com VisitKerteminde Langeland Tourist Office SVENDBORG visitkerteminde.com my-langeland.com Ferry Als - Bøjden VisitLillebaelt VisitNordfyn visitlillebaelt.com visitnordfyn.com VisitNyborg VisitSvendborg visitnyborg.com visitsvendborg.com RUDKØBING VisitOdense Ærø Tourist Office ÆRØ visitodense.com visitaeroe.com ÆRØSKØBING LANGELAND LIKE A DREAM COME TRUE - THE ISLAND FYN Endless beaches and a semingly limitless number of cultural or jump aboard a ferryboat to take a trip to the many islands experiences: on Fyn, tranquility and relaxation goes hand in around Fyn. -

Songs by Artist

TOTALLY TWISTED KARAOKE Songs by Artist 37 SONGS ADDED IN SEP 2021 Title Title (HED) PLANET EARTH 2 CHAINZ, DRAKE & QUAVO (DUET) BARTENDER BIGGER THAN YOU (EXPLICIT) 10 YEARS 2 CHAINZ, KENDRICK LAMAR, A$AP, ROCKY & BEAUTIFUL DRAKE THROUGH THE IRIS FUCKIN PROBLEMS (EXPLICIT) WASTELAND 2 EVISA 10,000 MANIACS OH LA LA LA BECAUSE THE NIGHT 2 LIVE CREW CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS ME SO HORNY LIKE THE WEATHER WE WANT SOME PUSSY MORE THAN THIS 2 PAC THESE ARE THE DAYS CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) TROUBLE ME CHANGES 10CC DEAR MAMA DREADLOCK HOLIDAY HOW DO U WANT IT I'M NOT IN LOVE I GET AROUND RUBBER BULLETS SO MANY TEARS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE UNTIL THE END OF TIME (RADIO VERSION) WALL STREET SHUFFLE 2 PAC & ELTON JOHN 112 GHETTO GOSPEL DANCE WITH ME (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & EMINEM PEACHES AND CREAM ONE DAY AT A TIME PEACHES AND CREAM (RADIO VERSION) 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS (DUET) 112 & LUDACRIS DO FOR LOVE HOT & WET 2 PAC, DR DRE & ROGER TROUTMAN (DUET) 12 GAUGE CALIFORNIA LOVE DUNKIE BUTT CALIFORNIA LOVE (REMIX) 12 STONES 2 PISTOLS & RAY J CRASH YOU KNOW ME FAR AWAY 2 UNLIMITED WAY I FEEL NO LIMITS WE ARE ONE 20 FINGERS 1910 FRUITGUM CO SHORT 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 21 SAVAGE, OFFSET, METRO BOOMIN & TRAVIS SIMON SAYS SCOTT (DUET) 1975, THE GHOSTFACE KILLERS (EXPLICIT) SOUND, THE 21ST CENTURY GIRLS TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 21ST CENTURY GIRLS 1999 MAN UNITED SQUAD 220 KID X BILLEN TED REMIX LIFT IT HIGH (ALL ABOUT BELIEF) WELLERMAN (SEA SHANTY) 2 24KGOLDN & IANN DIOR (DUET) WHERE MY GIRLS AT MOOD (EXPLICIT) 2 BROTHERS ON 4TH 2AM CLUB COME TAKE MY HAND -

Black Iiistdbym

, -' i' <' - ~ . The"ShadeDts' Voice for Over 50 Yean ~ VoI.54 No.9 Baruch College, CUNY February 17, 1917 16,017 DRUN:K' REGISTER STUDENT FOR 'SPRING '87 INJURED By JACQUEUNE MULHERN By NEERAJ VOHRA A total of 16,017 students An intoxicated male student registered for Spong 1987 classes, received minor injuries outside the ~~lanl1"OOre3~e-or-moreLhaIl6O(tfrom- nt Center.rafter attending a Spring 1986, according to Thomas club party on the evening of Dec. McCarthy the registrar. However, 12, 1986, according to Robert T. only 8,291 of these students enroll- Georgia, acting dean of students. ed in January; the other 7,726 took Georgia did not identify the stu advantage of early registration in dent and said, "I would not want to December, the most since the pro- -violate anyone's privacy." Georgia TIle ......... 01 tile Sa' '11 I. e.ter IIfIer..,....TnI.........eo.puy gram began. declined to go much further into tnIdE "Qed.oI o.to It. detail and said that his office was Seniors and Baruch Scholars "looking into the matter to identify New Deans received first priority in registering the individual involved and the and, therefore, were most likely to nature and cause of the incident." Sought TRUCK SPRAYS OIL receive their first choices for classes. According to Georgia, the'dean Juniors, sophomores and, fmally, of students'office wa~ also attemp- SEARCH ON.~_WALL OF freshmen were then proc~_. ,_ ting to determine whether the col- ' McCarthy Said, "One of the big- lege's alcohol policy guidelines were' COMMITTEES STUDENT CENTER gest problems is not with the violated, and whether "additional FORMED • seniors, but sophomores and preventive measures need to be in juniors and the problems they have troduced to avoid such occurrences By LINDA ZUECB By JOHN GRECO aad \ t:iDdi~ _Ule basic. -

University of California Santa Cruz the Production Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE PRODUCTION OF PLACE, URBAN DEVELOPMENT, AND PUBLIC SPACES IN AN EMERGING TOURIST ECONOMY IN NORTHEASTERN BRAZIL A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ANTHROPOLOGY with an emphasis in LATIN AMERICAN AND LATINO STUDIES by Christian T. Palmer December 2014 The Dissertation of Christian T. Palmer is approved: _____________________________________ Mark Anderson, Chair _____________________________________ Andrew Mathews _____________________________________ Megan Moodie ___________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Christian T. Palmer 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures v Abstract vi Acknowledgments viii Chapters 1. Introduction 1 Theorizing tourism, identity, and place 6 Local histories and relationships to place 16 Brazilian regionalism and Northeastern Brazil 18 Brazilian Nationalism and Landscape 22 Cosmopolitan tropicalism, the Brazilian Hawaii 24 Ethnographic process 28 Overview of chapters 31 Interlude: Fishing in Itacaré 36 2. Surfers “discover” Itacaré: performance, place, and 46 identity in the tropics Counter culture, the global sixties, and the development of 50 surfing in Brazil Surfers arrive in Itacaré 56 Surfers' habitus and the embodied performance of place 61 Surfers transform the city 69 Environmentalism and surfing 76 The Brazilian Hawaii 81 3. State sponsored tourism and conservation 93 The paving of BR001 and PRODETUR 97 Terra devolutas as public land and -

A Multimodal Novel

Interfaces Image Texte Language 38 | 2017 Crossing Borders: Appropriations and Collaborations Strategies of Engagement in Using Life: A Multimodal Novel Marie Thérèse Abdelmessih Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/314 DOI: 10.4000/interfaces.314 ISSN: 2647-6754 Publisher: Université de Bourgogne, Université de Paris, College of the Holy Cross Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2017 Number of pages: 105-126 ISSN: 1164-6225 Electronic reference Marie Thérèse Abdelmessih, “Strategies of Engagement in Using Life: A Multimodal Novel”, Interfaces [Online], 38 | 2017, Online since 13 June 2018, connection on 07 January 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/interfaces/314 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.314 Les contenus de la revue Interfaces sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 105 “STRATEGIES OF ENGAGEMENT IN USING LIFE: A MULTIMODAL NOVEL” Marie Thérèse Abdelmessih Multimodality is not new to Egyptian culture whose ancient sign system was the hieroglyph (Lambeens & Pint 240); correspondingly, ancient Egyptian two dimensional mural art was at times sequential, illustrated by hieroglyphic inscriptions. Moreover, a bas-relief dating to the Old Kingdom circa 2,000 BCE at Cairo Museum may be considered as the earliest pictorial cartoon, according to Afaf L. Margot. It bears political insinuations by depicting a conflicting relationship between the keeper and the sacred baboons in his charge (Margot 3). Later, Coptic and medieval Arabic manuscripts combined text and image (Coptic Museum). In modern times, Egyptian cartoons evolved in the second half of the nineteenth century with the founding of newspapers in 1870.