Otaku and the Numinous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protoculture Addicts #40

Sample file Sample file Sample file CONTENTS 5 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ STAFF Publisher EDITORIAL Claude J. Pelletier Borders Of The Mind .......................................................................................... 6 Editor-in-chief Martin Ouellette WHAT'S GOING ON? Contributors ECHOES FROM THE NET AND OTHER NEWS ........................................................... 7 Ghislain Barbe, Normand Bilodeau ANIME ............................................................................................................... 8 Miyako Graham, Josée Hardy MANGA .......................................................................................................... 10 James Standen Taylor ANIME PRODUCTS ............................................................................................. 12 Layout NEW RELEASES ................................................................................................. 13 The Safe House Group Cover Ghislain Barbe REVIEWS CD: Robotech Perfect Soundtrack Album ............................................................ 18 Illustrations BOOK: Bringing Home The Sushi ....................................................................... 27 Ghislain Barbe MODELS: Shogun Warriors & Gundam Master Grade ........................................... 37 Proofreading MANGA: Adolf ................................................................................................. 42 Dominique Durocher ANIME: PA'S PICK ............................................................................................. -

Pre-1970 1971-1975

Suggested Series for Analysis SP.270 Spring 2004 This document lists a sample of the well-known or significant anime series (with few exceptions, 26+ episodes) released between 1963 and 1998. If you know very little about anime before 1998, consider one of the series listed below. All series are ordered by the original year broadcast (TV) or released (OVA). In addition, to locate the series for viewing, you can check availability from the sources listed. This list draws from the instructor’s personal knowledge, The Anime Encyclopedia, credit rolls, box information, and various websites on the Internet. You are no means constrained to this list. There are orders of magnitude more animation that you may select for your series analysis; this list is only a small sample. All errors are, of course, the instructor’s; if you discover an error, please notify him. Format: DVD (D), VHS (V), Digital Fansub (F). Unless listed otherwise, VHS tapes and Digital Fansubs are Japanese language dialogue with English subtitles. DVDs are Region 1 with Japanese and English dialogues, and English subtitles. Instructor (F): Available from the instructor’s collection, and placed in the Film Office in advance for student use. These titles will remain in the Film Office through Spring Break. Please return these titles to the Film Office as soon as possible. MIT Anime: Available from the MIT Anime distro library. All titles are on VHS. Instructor: Available from the instructor’s collection. Students who choose these series should contact the instructor promptly, who will deposit the materials in the Film Office. -

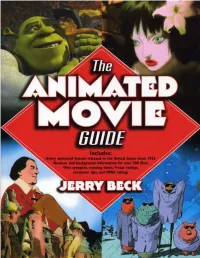

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

Logan County Master Gardener Training Course

August 2018 P: 405-282-2489 CHECK OUT THE F: 405-282-0192 COMMUNITY CALENDAR WWW.CITYOFGUTHRIE.COM AT WWW.GUTHRIECHAMBER.COM Logan County Master Gardener training course Do you have what it takes to become a Master Gardener? Master Gardeners are individuals who take an active interest in their lawns, trees, shrubs, flowers and gardens. They are enthusiastic, willing to learn and to help others, and want to share their knowledge and interest with others. The Logan County Master Gardener training course is scheduled to begin September 19th and will continue for 13 weeks through grad- uation on December 11th. The registration for the course is $100 which includes: weekly lecture from experts in the field, a notebook composed of OSU fact sheets ranging from topics on soils to Oklahoma Proven plants, fertilizers and pesticides, and much more. Along with completing the 13-week certification course, Master Gardeners must also complete 20 hours of volunteer service and 20 hours of continuing education each year to maintain their Master Gardener volunteer status. Master Gardener program will be taught at the Logan County Extension Office, located at 215 Fairgrounds Road, Guthrie, OK. Sessions will be held from 1-4:30 pm on a weekly basis. If you are interested in joining a Master Gardener class, please contact the Logan Coun- ty OSU Extension Office at 405-282-3331 for more information 2018 LOGAN COUNTY MASTER GARDENER CLASS SCHEDULE Week 1 - September 19th, Intro to Master Gar- Week 5 - October 17th, Plant Disease, Jen Olson Week 10 - November -

Tarot and the Eye of Escaflowne

Tarot and the Eye of Escaflowne Written by Monica Ho The Vision of Escaflowne, a 26 episode anime series created by Shoji Kawamori, is a complex struggle between the visible and the invisible, between Will and Fate. Sure, we may all be sick of this overused and cliched theme, but The Vision of Escaflowne takes it to a deeper, more existential level -- do certain events happen by twist of fate or does the past influence future events? Furthermore, how much of the future is determined by past and present actions? These questions cannot be easily answered upon initial inspection. Although The Vision of Escaflowne doesn't explicitly answer the questions that it poses, it does present a thought continuum using an ancient game: the tarot. Although the origins of modern tarocchi are still widely debated, its esoteric designs were created to answer the questions of past, present and future. The tarot has never been a stranger to the fantastic world of Japanimation: In Jo Jo's Bizarre Adventure, each Stand user's unique power is X, High Priestessrepresented by a tarot card. Unfortunately, I couldn't establish any resemblance between the characteristic of the card and the power of the cardholder. And in X/1999, a popular manga by CLAMP, each serialized volume is graced with a tarot card in a meaningful sequence based on a certain character of the manga. The idea is not original, but who dares to complain about CLAMP art? In The Vision of Escaflowne, though, the tarot is no longer a plot ornament. Rather, we get a much more intimate picture of the tarot, because the main protagonist, Hitomi, is herself a tarot reader, and her readings have a disturbing influence on the development of the story.. -

Guia De Animes Storage

GUIA DE ANIMES STORAGE # 009‐1 07 Ghost 3x3 Eyes A A Chuva, a Menina e Minha Carta Accel World Agatha Cristie no Matantei Poirot to Marple Ah! Megami Sama – Coletânea Ah! Megami Sama (TV) Ah! Megami Sama Sorezore no Tsubasa (TV2) Ah! Megami Sama OVAs Ah! Megami Sama Movie Ah! Mini Goddnes Akira Amnesia Angel Beats Angel Sanctuary Ano Natsu de Matteru Anne no Nikki (Anne Frank Diary) AnoHana Another Ao no Exorcist Ao no Exorcist Movie Appleseed Old Appleseed 2004 Appleseed Ex‐Machina Aru Tabibito no Nikki Arve Rezzle Asura Avatar (Livro I, II e III) (dublado) Azumanga Daioh Azumanga Daion Movie B Basilisk Bastard Batman Gotham Knight Bayonetta‐Bloody Fate Beelzebub Berserk Berserk Movies Black Rock Shooter (TV) Black Rock Shooter OVA Bleach Coletânea Bleach TV Bleach Movie 1 Bleach Movie 2 Bleach Movie 3 Bleach OVAs Blood: The Last Vampire Blood Plus Blood‐C Blood‐C: The Last Dark Blood Lad Brave Story Btooom! Bucky (dublado) C Captain Tsubasa J (dublado) Captain Tsubasa Road to 2002 (dublado) Cencoroll Chobits Clannad Clannad Movie Clannad After Story Claymore Code Geass Code Geass R2 Code Geass Boukoku no Akito Colorful Coppelion Cowboy Bebop Cowboy Bebop Movie D Dantalian no Shoka Date a Live Deadman Wonderland Death Billiards Death Note (dual audio) Death Note Rewrite Devil May Cry D‐Gray Man Dog Days Dog Days 2 Dragon Ball ‐ Coletânea Dragon Ball (dublado) Dragon Ball Movies (dublado) Dragon Ball Z (dublado) Dragon Ball Z Movies (dublado) Dragon Ball Z Especiais Dragon Ball GT (dublado) Dragon Ball Especial 10 Anos Dragon Ball A Batalha -

ANIME OP/ED (TV-Versio) Japahari Net - Retsu No Matataki Maximum the Hormone - ROLLING 1000 Toon

Air Master ANIME OP/ED (TV-versio) Japahari Net - Retsu no matataki Maximum the Hormone - ROLLING 1000 tOON 07 Ghost Ajin Yuki Suzuki - Aka no Kakera flumpool - Yoru wa Nemureru kai? Mamoru Miyano - How Close You Are 91 Days Angela x Fripside - Boku wa Boku de atte ELISA - Rain or Shine TK from Ling Tosite Sigure - Signal Amanchu Maaya Sakamoto - Million Clouds 11eyes Asriel - Sequentia Ange Vierge Ayane - Arrival of Tears Konomi Suzuki - Love is MY RAIL 3-gatsu no Lion Angel Beats BUMP OF CHICKEN - Answer Aoi Tada - Brave Song .dot-Hack Lisa - My Soul Your Beats See-Saw - Yasashii Yoake Girls Dead Monster - My Song Bump of chicken - Fighter Angelic Layer .hack//g.u Atsuko Enomoto - Be my Angel Ali Project - God Diva HAL - The Starry sky .hack//Liminality Anime-gataris See-Saw - Tasogare no Umi GARNiDELiA - Aikotoba .hack//Roots Akagami no Shirayuki hime Boukoku Kakusei Catharsis Saori Hayami - Yasashii Kibou eyelis - Kizuna ni nosete Abenobashi Mahou Shoutengai Megumi Hayashibara - Anata no kokoro ni Akagami no Shirayuki hime 2nd season Saori Hayami - Sono Koe ga Chizu ni Naru Absolute Duo eyelis - Page ~Kimi to Tsuzuru Monogatari~ Nozomi Yamamoto & Haruka Yamazaki - Apple Tea no Aji Akagi Maximum the Hormone - Akagi Accel World May'n - Chase the World Akame ga Kill Sachika Misawa - Unite. Miku Sawai - Konna Sekai, Shiritakunakatta Altima - Burst the gravity Rika Mayama - Liar Mask Kotoko - →unfinished→ Sora Amamiya - Skyreach Active Raid Akatsuki no Yona AKINO with bless4 - Golden Life Shikata Akiko - Akatsuki Cyntia - Akatsuki no hana -

Jumpchain List

1 1984 Crux 2 007 3 7th Tower SB 4 80’s Action Movies Marvel Anon 5 8bit Theater 6 A Brother’s Price Bean_Counter/Brother_Anon 7 A Certain Magical Index 8 A Certain Scientific Railgun Reploid 9 A Collection of Strange Tales by Junji Ito (伊藤潤二怪談録 ) dirge_/Cadenza Alstrea 10 A Geek’s Guide: Corporation of Occult Research and Extermination (C.O.R.E. Quest) SB Disposable_Face 11 A Song of Ice and Fire Cool cats don’t trip 12 A Spartan's War SB WIP Bluesnowman 13 A Super Mario... Thing Cataquack Warrior 14 Aberrant 15 Ace Attorney 16 Ace Combat Red 17 Achron Abhorsen_Anon? 18 ACTRAISER eagerDigger 19 Actual Cannibal Shia LaBeouf SB Joke? 20 Addams Family SB WIP doctor geary 21 Advance Wars 22 Adventure Time Cool cats don’t trip 23 Afterlife SB Bluesnowman 24 Against The Gods SB blackshadow111 25 Age of Empires III WIP 26 Age of Mythology stupid_dog 27 Age of Wonders 28 Ah! My Goddess 29 Aion Aionon 30 Ajin: Demi-Human WIP 31 Akagi 32 Akame Ga Kill 33 AKB49 - Renai Kinshi Jourei (The Rules Against Love) FreyrAnon 34 Aladdin SB blackshadow111 35 Alan Wake Obfuscation 36 Aldnoah.Zero Valeria; Alice 37 Alice – Adventures in the Wonderland Mad_Hatter 38 Alice – Through the Looking Glass Mad_Hatter 39 Alien 40 Alien Vs Predator myrmidont 41 Alpha Centauri 42 Alpha Protocol 43 Alterworld D. Rus Aionon 44 Amazing Island Gauntlet Gene 45 American Horror Story WIP 46 American McGee’s Alice 47 Anarchy Reigns 48 Angel Notes Valeria 49 Anima: Beyond Fantasy Anon Heart/Shadlith 50 Animal Crossing YJ_Anon 51 Animorphs 52 Anita Blake, Vampire Hunter Reddit -

UBC Anime Club Catalogue Please Click on the Picture for More Detail

UBC Anime Club Catalogue Please click on the picture for more detail Picture English Kanji/Japanese Romaji Type Disks Episodes Note to end User Due to word problem, the hyperlink can’t be created, please visit .hack//SIGN - - Series 6 26 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/.hack//Sign for more detail. Ai Yori Aoshi 藍より青し - Series 5 24 Akira - - Movie 1 Alien Nine - - OVA 1 4 星方天使エンジェルリンク Angel Links Seiho Tenshi Enjeru Rinkusu Series 4 13 ス Angelic Layer - - Series 5 26 アニメ制作進行くろみちゃ Anime Seisaku Shinko Animation Runner Kuromi OVA 1 ん Kuromi-chan This is the bonus disk of Appleseed the Appleseed - - Bonus 2 Motion Picture, please do not ask me where the movie disk is, I wish I know…… Arcadia of my Youth わが青春のアルカディア Waga Seishun no Arukadia Movie 1 Arjuna 地球少女アルジュナ Chikyu Shojo Arujuna Series 3 10 Incomplete: missing disk 1 and 4 There has been multiple Astroboy TV Astro Boy 鉄腕アトム Tetsuwan Atomu Series 8 51 series, this is the 1980 release. Incomplete: missing after disk 5 (after Aura Battler Dunbine 聖戦士ダンバイン Seisenshi Dambain Series 5 21 episode 21) Avenger - - Series 3 13 Azumanga Daioh あずまんが大王 - Series 5 26 Baccano! - - Series 3 16 Banner Of The Stars 星界の戦旗 Seikai no Senki Series 3 13 Banner Of The Stars II 星界の戦旗 II Seikai no Senki II Series 3 10 Basutado!! Ankoku no Bastard!! BASTARD!! 暗黒の破壊神 OVA 1 6 Hakaishin Beck: Mongolian Chop Squad - - Series 4 Berserk - - Series 6 25 Betterman - - Series 6 26 Black Lagoon - - Series 3 12 Black Lagoon: The Second - - Series 3 24 Barrage Blue Gender - - Series 8 26 Blue Gender: the Warrior - - Movie 1 -

Awnmag5.12.Pdf

Table of Contents MARCH 2001 VOL.5 NO.12 4 Editor’s Notebook What good is technology? 5 Letters: [email protected] TECHNOLOGY 6 The Technology Circle Over the past five years the changes in special effects technology for film and television have been monumental, causing large shifts and new issues for production companies and the soft- ware/hardware companies that service them. Bruce Manning outlines the issues and then sits down with Richard Taylor to discuss. Visit us online to see enlarged images and additional infor- mation on Richard’s work. 12 Low-Cost Solutions, High-End Results With today’s new software packages becoming more and more efficient for less and less money, one can definitely do more with less. John Edgar Park discusses the different software and hard- ware combos that can get you on the fast track to great looking CGI work. Go online to see detailed specs on Strata 3D and Hash Animation:Master online at: http://www.awn.com/mag/issue5.12/5.12pages/parkblurring.php3. 16 Making It To The Web Exporting your animation to Flash so that it plays smoothly and soundly over the Internet is get- ting more complicated with every new product crowing about its “Flash-export capability.” Mark Winstanley is here to make sense of it all for you. 2001 ADDITIONAL FEATURES 20 There Once Was A Man Called Pjotr Sapegin From Russia to his new home of Norway, Pjotr Sapegin is bringing his own twisted sense of humor to his re-worked fairy tales. Who is this man behind a salt controlling troll, a genital lov- ing cat and a rat seeking romance? Chris Robinson investigates. -

Thesis Adviser Recommendation Letter

THESIS ADVISER RECOMMENDATION LETTER This thesis entitled “THE APPLICATION OF JAPANESE‟S SOFT POWER IN THE U.S.A: THE CASE STUDY OF ANIME AND MANGA (2000-2007)” prepared and submitted by Muhammad Aji Barli in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor‟s degree in the School of Humanities has been reviewed and found to have satisfied the requirements for a thesis fit to be examined. I therefore recommend this thesis for Oral Defense. Cikarang, Indonesia, April, 2015 Teuku Rezasyah, Ph.D i DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this thesis, entitled “The Application Of Japanese‟s Soft Power In The U.S.A: The Case Study Of Anime And Manga (2000- 2007)” is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, an original piece of work that has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, to another university to obtain a degree. Cikarang, Indonesia, April, 2015 Muhammad Aji Barli ii PANEL OF EXAMINER APPROVAL SHEET The Panel of Examiners declare that the thesis entitled “THE APPLICATION OF JAPANESE‟S SOFT POWER IN THE U.S.A: THE CASE STUDY OF ANIME AND MANGA (2000-2007)” that was submitted by Muhammad Aji Barli majoring in International Relations from the Faculty of International Relations, Communication and Law was assessed and approved to have passed the Oral Examinations on 15 April, 2015. Hendra Manurung, MA. Chair Panel Examiner Eric Hendra, Ph.D Examiner II Teuku Rezasyah, Ph.D Adviser iii ABSTRACT Title: The Application Of Japanese‟s Soft Power In The U.S.A: The Case Study Of Anime And Manga (2000-2007) This research attempts to describe about the application of the Japanese cultural diplomacy in the U.S in order to promote understanding of Japan that leads to better image from 2000 until 2010. -

Anime Fusion 2017 11 11 Anime Fusion 2017 Gaming Rooms Video Gaming Summer Room

1 Anime Fusion 2017 DRAFT Posting about Anime Fusion? Use #AnimeFusion2017 to join our online conversation! Welcome General Information ................................................................................ 3 Costume Contest ......................................................................................... 5 Room Parties ................................................................................................... 7 Guests of Honor .......................................................................................... 8 Autograph Sessions .................................................................................... 9 Gaming Rooms ............................................................................................. 12 Full Schedule ............................................................................................... 14 Panels & Events ............................................................................................ 21 Video Rooms .................................................................................................. 27 Credits .............................................................................................................. 32 A Note from the Chair Welcome all to Anime Fusion: Racing Through Time. This is year six. Quad Cities Anime is proud to present to you the fruits of many staffers’ labor. A big thanks goes to you, the attendees, for whom we put hours of effort into planning this gathering. Another thanks goes to the Hilton DoubleTree Park Place. If