Crowds at Outdoor Music Festivals: an Examination of Crowd Psychology and Its Implications for the Environmental Health Practitioner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. Dennis Thomas. Concert and Live Music Photography. Pro Tips From

CONCERT AND LIVE MUSIC PHOTOGRAPHY Pro Tips from the Pit J. DENNIS THOMAS Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK © 2012 Elsevier Inc. Images copyright J. Dennis Thomas. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein. -

Prbis Brainscan

VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 MAY/JUNE 2011 PRBIS BRAINSCAN LIFE BEYOND ACQUIRED BRAIN INJURY POWELL RIVER BRAIN INJURY SOCIETY Brain Injury 101 – a Marathon for Awareness Date: Saturday June 11, 2011 Location: Pacific Coastal Highway Our new marathon goal - the Pacific Coastal Highway, which includes Highway 101 Brain Injury 101 – a Marathon for Aware- ness For the purpose of: •promoting public awareness of Acquired Brain Injury •raising money to allow us to continue helping our clients and their caregivers. PRBIS BRAINSCAN Page 2 Walk For Awareness of Acquired Brain Injury In 2009 we walked the length of our section of Highway 101. This part of the Pacific Coastal Highway is 56 kilometers in length, start- ing in Lund, passing through Powell River and ending in Saltery Bay, where the ferry connects to the next part of Highway 101. This first walk was completed over 3 days. Participants were clients, professionals and ordinary citizens who wanted to take part in this public awareness project. Money was raised with pledges of sup- port to the walkers as well as business sponsors for each kilometer. For the second year, we offered more options on distance to com- plete – 1, 2, 5 or 10 kilometers, or for the truly fit, the entire 56 kilo- meters. Those who participated did so by walking, running or bicy- cling. We invited not only clients, family and ordinary citizens, but also contacted athletes, young athletes and sports associations to join our cause and complete the 56 kilometers ultra-marathon. _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 Page 3 PRBIS BRAINSCAN Page 4 The Too Much Sugar Easter Celebration Linda Boutilier, our resident chocolatier and cake decorator, once again graced our lovely little office with yummy goodness. -

Public Health Management at Outdoor Music Festivals"

PUBLIC HEALTH MANAGEMENT AT OUTDOOR MUSIC FESTIVALS CAMERON EARL Ass Dip Health Surveying; Masters in Community and Environmental Health Graduate Certificate in Health Science Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Health Science, School of Public Health Faculty of Health Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane January 2006 2 Thesis Abstract Background Information: Outdoor music festivals (OMFs) are complex events to organise with many exceeding the population of a small city. Minimising public health impacts at these events is important with improved event planning and management seen as the best method to achieve this. Key players in improving public health outcomes include the environmental health practitioners (EHPs) working within local government authorities (LGAs) that regulate OMFs and volunteer organisations with an investment in volunteer staff working at events. In order to have a positive impact there is a need for more evidence and to date there has been limited research undertaken in this area. The research aim: The aim of this research program was to enhance event planning and management at OMFs and add to the body of knowledge on volunteers, crowd safety and quality event planning for OMFs. This aim was formulated by the following objectives. 1. To investigate the capacity of volunteers working at OMFs to successfully contribute to public health and emergency management; 2. To identify the key factors that can be used to improve public health management at OMFs; and 3. To identify priority concerns and influential factors that are most likely to have an impact on crowd behaviour and safety for patrons attending OMFs. -

University of Southern Queensland Behavioural Risk At

University of Southern Queensland Behavioural risk at outdoor music festivals Aldo Salvatore Raineri Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Professional Studies at the University of Southern Queensland Volume I April 2015 Supervisor: Prof Glen Postle ii Certification of Dissertation I certify that the ideas, experimental work, results, analyses and conclusions reported in this dissertation are entirely my own effort, except where otherwise acknowledged. I also certify that the work is original and has not been previously submitted for any other award, except where otherwise acknowledged. …………………………………………………. ………………….. Signature of candidate Date Endorsement ………………………………………………….. …………………… Signature of Supervisor Date iii Acknowledgements “One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of seeing things.” Henry Miller (1891 – 1980) An outcome such as this dissertation is never the sole result of individual endeavour, but is rather accomplished through the cumulative influences of many experiences and colleagues, acquaintances and individuals who pass through our lives. While these are too numerous to list (or even remember for that matter) in this instance, I would nonetheless like to acknowledge and thank everyone who has traversed my life path over the years, for without them I would not be who I am today. There are, however, a number of people who deserve singling out for special mention. Firstly I would like to thank Dr Malcolm Cathcart. It was Malcolm who suggested I embark on doctoral study and introduced me to the Professional Studies Program at the University of Southern Queensland. It was also Malcolm’s encouragement that “sold” me on my ability to undertake doctoral work. -

Punk Rock and the Socio-Politics of Place Dissertation Presented

Building a Better Tomorrow: Punk Rock and the Socio-Politics of Place Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jeffrey Samuel Debies-Carl Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Townsand Price-Spratlen, Advisor J. Craig Jenkins Amy Shuman Jared Gardner Copyright by Jeffrey S. Debies-Carl 2009 Abstract Every social group must establish a unique place or set of places with which to facilitate and perpetuate its way of life and social organization. However, not all groups have an equal ability to do so. Rather, much of the physical environment is designed to facilitate the needs of the economy—the needs of exchange and capital accumulation— and is not as well suited to meet the needs of people who must live in it, nor for those whose needs are otherwise at odds with this dominant spatial order. Using punk subculture as a case study, this dissertation investigates how an unconventional and marginalized group strives to manage ‘place’ in order to maintain its survival and to facilitate its way of life despite being positioned in a relatively incompatible social and physical environment. To understand the importance of ‘place’—a physical location that is also attributed with meaning—the dissertation first explores the characteristics and concerns of punk subculture. Contrary to much previous research that focuses on music, style, and self-indulgence, what emerged from the data was that punk is most adequately described in terms of a general set of concerns and collective interests: individualism, community, egalitarianism, antiauthoritarianism, and a do-it-yourself ethic. -

Safe and Healthy Mass Gatherings AUSTRALIAN DISASTER RESILIENCE HANDBOOK COLLECTION Safe and Healthy Mass Gatherings Manual 12

Australian Disaster Resilience Handbook Collection MANUAL 12 Safe and Healthy Mass Gatherings AUSTRALIAN DISASTER RESILIENCE HANDBOOK COLLECTION Safe and Healthy Mass Gatherings Manual 12 Attorney-General’s Department Emergency Management Australia © Commonwealth of Australia 1999 Attribution Edited and published by the Australian Institute Where material from this publication is used for any for Disaster Resilience, on behalf of the Australian purpose, it is to be attributed as follows: Government Attorney-General’s Department. Edited, typeset and published by Emergency Source: Australian Disaster Resilience Manual 12: Safe Management Australia and Healthy Mass Gatherings, 1999, Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience CC BY-NC Printed in Australia by Better Printing Service Using the Commonwealth Coat of Arms Copyright The terms of use for the Coat of Arms are available from The Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience the It’s an Honour website (http://www.dpmc.gov.au/ encourages the dissemination and exchange of government/its-honour). information provided in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia owns the copyright in all Contact material contained in this publication unless otherwise noted. Enquiries regarding the content, licence and any use of this document are welcome at: Where this publication includes material whose copyright The Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience is owned by third parties, the Australian Institute for 370 Albert St Disaster Resilience has made all reasonable efforts to: East Melbourne Vic 3002 • clearly label material where the copyright is owned by Telephone +61 (0) 3 9419 2388 a third party www.aidr.org.au • ensure that the copyright owner has consented to this material being presented in this publication. -

SPRING 2015 NUMBER 1 Page Ii 03-24.Docx (Do Not Delete) 3/24/2015 5:57 PM

SJA 2-1 toc 03-24.docx (Do Not Delete) 3/24/2015 5:47 PM THE LEGAL APPRENTICE FOREWORD ....................................................................................... v Dean Jeffrey P. Grossmann WELCOME NOTE ............................................................................ vii Honorable John F. Blawie ARTICLES WHAT HAPPENED TO THE 9/11 CROSS ............................................. 1 Andres Santamaria DIAMONDS ARE A GIRL’S BEST FRIEND ........................................... 7 Gabriella Labita HAIR TODAY, GONE FROM THE TEAM ........................................... 13 Brian Stevens STAGE DIVING ............................................................................... 19 Jenane Jeanty LAW STUDENTS AND UNDERGRADUATES LEARNING TOGETHER AT THE SECURITIES ARBITRATION CLINIC ............................. 23 Professor Christine Lazaro VOLUME 2 SPRING 2015 NUMBER 1 Page ii 03-24.docx (Do Not Delete) 3/24/2015 5:57 PM ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF PROFESSIONAL STUDIES OFFICES OF ADMINISTRATION AND FACULTY 2014 – 2015 JEFFREY GROSSMANN, J.D. DEAN ELLEN TUFANO, PH.D. ASSOCIATE DEAN * * * ANTOINETTE COLLARINI-SCHLOSSBERG, J.D. CHAIRPERSON CRIMINAL JUSTICE, LEGAL STUDIES, HOMELAND SECURITY BERNARD HELLDORFER, J.D. DIRECTOR LEGAL STUDIES MARY NOE, J.D. ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR EDITOR JAMES CROFT, J.D. ASSISTANT PROFESSOR ASSISTANT EDITOR pg iii-iv.docx (Do Not Delete) 3/13/2015 12:19 PM THE LEGAL APPRENTICE FACULTY ADVISORY BOARD JAMES CROFT, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR B.A., J. D. ALBANY UNIVERSITY; ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY, SCHOOL -

Guidelines for Concerts, Events and Organised Gatherings

Guidelines for concerts, events and organised gatherings and organised concerts,Guidelines for events Guidelines for concerts, events and organised gatherings December 2009 Produced by Environmental Health Directorate DEC’09 23824 HP11275 © Department of Health 2009 Acknowledgements The Department of Health would like to thanks the Drug and Alcohol Office for their input and assistance in the production of this resource. The Department of Health also extends its thanks to all of the other key industry groups, government agencies and colleagues that provided valuable input. Guidelines for concerts, events and organised gatherings Contents Part A – background and administrative considerations Section 1 – background 1.1 Introduction 5 1.2 About this resource 6 1.3 How to use this resource 7 1.4 Approvals/Applications 8 Section 2 – roles and responsibilities 2.1 Roles and responsibilities 11 Section 3 – Administrative considerations 3.1 General administrative considerations 21 3.2 Insurance requirements 22 Part b – guidelines Section 4 – creating an accessible event and a risk management plan Guideline 1: Venue suitability 24 Guideline 2: Creating an accessible event 24 Guideline 3: Preliminary event rating 25 Guideline 4: Risk management 26 Guideline 5: Emergency management 30 Guideline 6: Medical first aid and public health considerations 33 Section 5 – public building approvals Guideline 7: Public building approvals 42 Guideline 8: Public building design 44 Guideline 9: Temporary structures 45 Guideline 10: Spectator stands 48 Guideline -

Hilltopics: Volume 5, Issue 2 Hilltopics Staff

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Hilltopics University Honors Program 9-22-2008 Hilltopics: Volume 5, Issue 2 Hilltopics Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hilltopics Recommended Citation Hilltopics Staff, "Hilltopics: Volume 5, Issue 2" (2008). Hilltopics. 83. https://scholar.smu.edu/hilltopics/83 This document is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hilltopics by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. always 100% smu-written volume five, issue two www.smu.edu/univhonors/hilltopics week of september 22, 2008 Is DISD making the grade? New policies say otherwise Beth Anderson Back in August, Dallas ISD implemented some controver- it will bring up a studentʼs average to do so. This is especially sial grading policy changes. These new policies are widely interesting because it brings up a lot of questions about what unpopular among teachers and parents, who claim that the education really means. If you can prove yourself on the policies are test, should too lenient you have to and that do home- they en- work? Iʼm courage la- sure we all ziness. In knew that my opinion, one bril- the policies liant un- do more derachiev- than that - er kid in they cause school who harm. never had F i r s t to do his of all, the homework c h a n g e s because he practically just caught make get- on quicker ting a real than every- grade easier one else. -

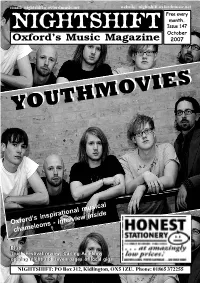

Issue 147.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 147 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 YOUTHMOVIESYOUTHMOVIES s inspirational musical Oxford’ interview inside chameleons - PlusPlus TruckTruck FestivalFestival review;review; CarlingCarling AcademyAcademy openingopening nightnight andand sevenseven pagespages ofof locallocal gigsgigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 TRUCK RECORDS launches THE BULLINGDON hosts a new two new regular live music club weekly live bands club night every NEWNEWSS nights this autumn. Starting from Thursday from 4th October. this month, on Thursday 11th, is Project:disco is run by the same Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Champions Of The World at the team who currently run Coo Coo Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Gladiator Social Club on Iffley Club at the Jericho Tavern. Bands Road. As well as a live set from and DJs interested in playing recent Magic Numbers support should contact Autumn at through; he’s a tough cookie”. act Danny Champion Of The [email protected], Surgeons have operated to repair World, there’ll be bingo, a cheese including MySpace links where two broken vertebrae and are auction and a disco. Meanwhile, possible. treating a smashed heel. Mickey is after being forced to move much of expected to make a full recovery, this year’s Truck Festival bill up THE THIEVES have split up. The although this may take several to Brookes University Union at band formed by Oxfordshire months. Commenting on the the last minute following the bothers Hal and Sam Stokes have cancellation of the show, Alan Day, floods, Truck have decided to go been resident in Los Angeles for the promoter for TCT Music, added, back with a once-a-term gig and past few years, constantly touring “We were really looking forward to club night. -

Hitting Rock Bottom: Staying Safe at Concerts, Music Festivals and Other

Hitting Rock Bottom: Staying Safe at Concerts, Music Festivals and Other Shows and Events www.eglaw.com 1-888-NYLAW12 Staying Safe at Concerts and Events When you are attending a concert, the last thing you want to worry about is that show’s organizers have not provided a safe place for you and your friends and family to enjoy yourselves. The nature of concerts has changed drastically over the years, leading to more injuries and accidents. There is more equipment and technology as productions have increased to include light shows, moving platforms, pyrotechnics and other special effects. Harder styles of music have encouraged some unsafe spectator activities, including moshing, thrashing, crowd surfing and the wall of death, where moshers split into two groups on either side of a pit and run into each other. In addition, multi-act festivals have become very popular, providing a range of popular and up- andcoming musical acts over the course of a day, evening, or weekend. Unfortunately, these concerts have been plagued with excessive drug use, with the most popular being MDMA, or Molly. It’s no surprise, then, that these all-day events have had issues with drug overdoses, dehydration and overheating, overcrowding and security issues. What Concert Organizers Need to Do to Keep You Safe There are many factors that go into creating a safe concert environment. In one of the deadliest concert accidents, sixteen people watching an outdoor pop concert in South Korea fell approximately six stories to their deaths when a ventilation grate they were standing on collapsed. To prevent such tragedies, it is important for concert venues to ensure that buildings and structures are well maintained, adhere to all regulations and are not above the limit in how many people they can safely hold. -

“Something About the Way You Look Tonight” Geneva Jackson Advised

“Something About the Way You Look Tonight” Popular Music Festivals as Rites of Passage in the Contemporary United States Geneva Jackson Advised by Judith Schachter Carnegie Mellon University Dietrich College Honors Fellowship Program Spring 2016 Acknowledgements This project was made possible by the love and support of many people, to whom I will be forever indebted. First, I would like to thank the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences, for the creation of the Honors Fellowship Program, through which I received additional support to begin work on my thesis over the summer of 2015. I am thankful for the opportunity to explore my nonacademic interests in an academic setting. Weekly meetings with the other fellows, Eleanor Haglund, Kaylyn Kim, Kaytie Nielsen, Sayre Olson, Lucy Pei, Chloe Thompson, and Laurnie Wilson, as well as our mentors Dr. Joseph Devine, Dr. Jennifer Keating-Miller, and Dr. Brian Junker, were invaluable in the formation of my topic focus. Thank you for the laughter and advice. I’d also like to express endless gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr. Judith Schachter, for her limitless encouragement, critical eye, and keen ability to parse out exactly I was trying to say when my phrasing became cumbersome. I would like also to acknowledge Dr. Scott Sandage for agreeing to consult with me over the summer and to thank him for telling the freshman-engineering-major version of me to consider a history degree. Special thanks must be given to my music festival partners, Catherine Kildunne, Emily Clark, Ian Einhorn, Sam Ho, and Anthony Comport, without whom field research would have been a woefully solitary task.