Habitat Use by Collared Crescentchest (Melanopareia Torquata)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lista De Aves De Salta (Birds Checklist)

Grupo de Observadores Salteños de Aves – GOSA Referencias – AA/AOP-SAyDS. Aves Argentinas/AOP y Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable. 2008. Categorización de las aves de la Argentina según su estado de conservación. Bs. As. – Contino, F. 1982. Aves del Noroeste Argentino. Universidad Nacional de Salta/Secretaria de Estado de Asuntos Agrarios, Dirección General de Recursos Naturales Renovables. Salta. – Di Giacomo A.S. (Ed.) 2005. Áreas Importantes para la Conservación de las Aves. Sitios prioritarios para la conservación de la biodiversidad. Temas de naturaleza y Conservación 5: 1-514 Aves Argentinas/AOP, Bs. As. – Narosky T. y D. Yzurieta. 1987 (y reeds.). Guía para la Identificación de las Aves de Argentina y Uruguay. Vázquez Mazzini Editores. Bs As. – Rodríguez, E. D. 2011 Aves de la Puna y los Altos Andes del Noroeste de Argentina. Mundo Editorial. Salta. – UICN, 2012. Lista Roja de Especies Amenazadas de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Versión 2012.1 . (junio) <http://www.iucnredlist.org> – SACC, 2012. Remsen, J. V., Jr., C. D. Cadena, A. Jaramillo, M. Nores, J. F. Pacheco, J. Pérez-Emán, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, D. F. Stotz, and K. J. Zimmer. Version june 2012. A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithologists Union. <http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.html> Fotos – Ricardo Cenzano, – Marcelo Gallegos, – Gabriela García, – Sebastián D´Ingianti, – Miguel González – Charly Hank, – Gabriel Núñez y – Flavio Moschione. Agradecimientos Ricardo Banchs, Marco Bulacio, Roberto Canelo, Sandra Caziani, Mariano Codesido, Gonzalo Cristofani, Marcelo Cuevas, Nancy Cruz, Sebastián D´Ingianti, Enrique Derlindati, Patrick Gado, Marcelo Gallegos, Juan Klimaitis, Mariano Libua, Leonidas Lizárraga, Nicéforo Luna, Abel Paredes, Mark Pearman, Javier San Cristóbal, Ana Laura Sureda, Leonardo Pastorino, Henán Povedano, Carina Rodríguez, Elio Rodríguez Iranzo, Ana Sandobal y Carlos Trucco. -

Pontifícia Universidade Católica Do Rio Grande Do Sul

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL FACULDADE DE BIOCIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ZOOLOGIA ANÁLISE FILOGENÉTICA DA FAMÍLIA RHINOCRYPTIDAE (AVES: PASSERIFORMES) COM BASE EM CARACTERES MORFOLÓGICOS Giovanni Nachtigall Maurício Orientador: Dr. Roberto E. Reis TESE DE DOUTORADO PORTO ALEGRE - RS - BRASIL 2010 SUMÁRIO RESUMO ...............................................................................................................................vi ABSTRACT ..........................................................................................................................vii 1 INTRODUÇÃO....................................................................................................................1 1.1 Sistemática e distribuição dos Rhinocryptidae .............................................................. 1 1.2 Classificação adotada................................................................................................... 15 2 MATERIAL E MÉTODOS................................................................................................ 17 2.1 Terminologia................................................................................................................ 17 2.2 Escolha dos terminais .................................................................................................. 18 2.2.1 Grupo interno ........................................................................................................ 18 2.2.2 Grupo externo....................................................................................................... -

SPLITS, LUMPS and SHUFFLES Splits, Lumps and Shuffles Thomas S

>> SPLITS, LUMPS AND SHUFFLES Splits, lumps and shuffles Thomas S. Schulenberg Based on features including boot colour and tail shape, Booted Racket-tail Ocreatus underwoodii may be as many as four species. 1 ‘Anna’s Racket- tail’ O. (u.) annae, male, Cock-of-the-rock Lodge, 30 Neotropical Birding 22 Cuzco, Peru, August 2017 (Bradley Hacker). This series focuses on recent taxonomic proposals – descriptions of new taxa, splits, lumps or reorganisations – that are likely to be of greatest interest to birders. This latest instalment includes: new species of sabrewing, parrot (maybe), tapaculo, and yellow finch (perhaps); proposed splits in Booted Racket-tail, Russet Antshrike, White-backed Fire-eye (split city!), Collared Crescentchest, Olive-backed Foliage-gleaner, Musician Wren, Spotted Nightingale-Thrush, Yellowish and Short-billed Pipits, Black-and- rufous Warbling Finch, Pectoral and Saffron-billed Sparrows, and Unicolored Blackbird; a reassessment of an earlier proposed split in Black-billed Thrush; the (gasp!) possibility of the lump of South Georgia Pipit; and re- evaluations of two birds each known only from a single specimen. Racking up the racket-tails Venezuela to Bolivia; across its range, the puffy ‘boots’ (leg feathering) may be white or buffy, Booted Racket-tail Ocreatus underwoodii is one and the racket-tipped outer tail feathers may be of the most widespread, and one of the fanciest, straight, or so curved that the outermost rectrices hummingbirds of the Andes. It occurs from cross over one another. 2 ‘Peruvian’ Racket-tail O. (u.) peruanus, female, Abra Patricia, San Martín, Peru, October 2011 (Nick Athanas/antpitta.com). 3 ‘Peruvian Racket-tail’ O. -

Brazil & Argentina Trip Report

Brazil & Argentina Trip Report Amazon Rainforest Birding Extension I 9th to 14th July 2016 Birds & Wildlife of the Pantanal & Cerrado I 14th to 23rd July 2016 Iguazú Extension I 23rd to 27th July 2016 Compiled by tour leader: Dušan M. Brinkhuizen Red-and-green Macaw by Paul Fox RBT Trip Report - Brazil I 2016 2 Our Rockjumper Brazil & Argentina I adventure of 2016 was an enormous success. The number of spectacular birds, mammals and other wildlife seen on this trip was simply overwhelming. And not to forget the fantastic sceneries of all the different habitats that we traversed. We started off with the pristine Amazon jungle of Cristalino lodge. Here we watched Harpy Eagle, Pompadour Cotinga, Amazonian Pygmy Owl, Razor-billed Curassow, Brown-banded Puffbird, Bare-eyed Antbird, Alta Floresta Antpitta but to name a few. We continued our birding trip visiting the amazing Pantanal forests and wetlands where we enjoyed spectacular birds including Hyacinth Macaw, Jabiru, Red- legged Seriema, Zigzag Heron, Nacunda Nighthawk, Scarlet-headed Blackbird, Great Rufous Woodcreeper, Grey-crested Cacholote, Campo Flicker, Chotoy Spinetail and so forth. Our Pantanal experience was also impressive in terms of mammal sightings which included Jaguar, Jaguarundi, Giant Anteater and Lowland Tapir to boot! The scenic Chapada dos Guimarães was superb birding too with Cerrado specialities such as Blue Finch, Collared Crescentchest, Chapada Flycatcher, Coal-crested Finch, Caatinga Puffbird, Yellow-faced Parrot and Horned Sungem. The last days of the tour were at the gargantuan Iguazú Falls just across the border in Argentina. Some of the stunning Atlantic Forest endemics that we bagged here included Saffron Toucanet, Black-fronted Piping Guan, Surucua Trogon, Speckle-breasted Antpitta, Green-headed Tanager, Black Jacobin and Buff-bellied Puffbird! Top ten birds as voted for by participants: 1. -

Home Range Size of the Collared Crescentchest, Melanopareia Torquata (Melanopareiidae) During the Reproductive Period in Southeastern Brazil

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 21(2), 109-113 ARTICLE June 2013 Home range size of the Collared Crescentchest, Melanopareia torquata (Melanopareiidae) during the reproductive period in southeastern Brazil Mieko Ferreira Kanegae 1,2 1 Laboratório de Ecologia de Aves, Departamento de Ecologia, Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão 321, Trav. 14, Cidade Universitária. CEP 05508-090 São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 2 Current address: Laboratório de Vertebrados, Departamento de Ecologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Av. Carlos Chagas Filho 373 Bl. A sala A2-84, Cidade Universitária. CEP 21941-902, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] Received on 5 June 2012. Accepted on 30 January 2013. ABSTRACT: The Collared Crescentchest (Melanopareia torquata) is an endemic bird of the Brazilian Cerrado that is regionally threatened with extinction. The goal of the present study was to estimate the Collared Crescentchest’s home range size during the reproductive period in a preserved reserve of Cerrado, where its population is small and declining. Data was obtained in October and November 2007 from 10 to 44 radio-locations for a total of 10 individuals. Only five individuals had their home range accumulation curves stabilized (average 36.4 ± 7.4 radio-locations). With the method of fixed Kernel (95%) average home range was 1.51 ± 0.52 ha and the core area (75%) was 0.68 ± 0.23 ha. I found that the species occupies a small home range during the reproductive period and that there was no home range overlap among the birds, although, some of them were observed very close to a neighbor’s area. -

THE BIG SIX Birding the Paraguayan Dry Chaco —The Big Six Paul Smith and Rob P

>> BIRDING AT THE CUTTING EDGE PARAGUAYAN DRY CHACO—THE BIG SIX Birding the Paraguayan Dry Chaco —The Big Six Paul Smith and Rob P. Clay 40 Neotropical Birding 17 Facing page: Quebracho Crested Tinamou Eudromia formosa, Teniente Enciso National Park, dept. Boquerón, Paraguay, March 2015 (Paul Smith / www.faunaparaguay.com) Above: Spot-winged Falconet Spiziapteryx circumcincta, Capilla del Monte, Cordoba, Argentina, April 2009 (James Lowen / www.jameslowen.com) t the end of the Chaco War in 1935, fought loss of some of the wildest and most extreme, yet under some of the harshest environmental satisfying birding in southern South America. A conditions of any 20th century conflict, The Dry Chaco ecoregion is a harsh a famous unknown Bolivian soldier chose environment of low thorny scrub and forest lying not to lament his nation’s defeat, but instead in an alluvial plain at the foot of the Andes. It is congratulated the Paraguayans on their victory, hot and arid, with a highly-adapted local flora of adding that he hoped they enjoyed the spoils: xerophytic shrubs, bushes and cacti. Few people the spiders, snakes, spines, dust, merciless sun… make it out to this vast wilderness, but those that If that soldier had been a birder, he might have do are guaranteed a special experience. In fact the seen it somewhat differently, and lamented the Chaco did not really open itself up to mainstream Neotropical Birding 17 41 >> BIRDING AT THE CUTTING EDGE PARAGUAYAN DRY CHACO—THE BIG SIX zoological exploration until the 1970s when Ralph adaptations to a diet that frequently includes Wetzel led expeditions to study the mammal life snakes (Brooks 2014). -

The Pantanal & Interior Brazil

The stunning male Horned Sungem (Eduardo Patrial) THE PANTANAL & INTERIOR BRAZIL 04 – 16/24 OCTOBER 2015 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL This 2015 Pantanal and Interior Brazil can be easily defined as a very successful tour. From the beginning to the end we delighted some of the best offers from the Cerrado (savannah), Pantanal and Amazon in central Brazil, totalizing 599 birds and 38 mammals recorded. For that we had to cover the big states of Minas Gerais on the east and the even bigger Mato Grosso on the west, in basically three different parts. First the two enchanting and distinct mountain ranges of Serra da Canastra and Serra do Cipó with their superb grasslands and rocky fields. Second the impressive Pantanal and its mega wildlife, plus the fine Cerrado and forests from Chapada dos Guimarães. And third the amazing diversity of the Amazon found in northern Mato Grosso, more precisely at the renowned Cristalino Lodge. This great combination of places resulted again in several memorable moments lived at fascinating landscapes watching some of the best birds (and mammals) from South America. Best remembrances certainly go to Greater Rhea, the rare Brazilian Merganser, Bare-faced and Razor-billed Curassows, Agami and Zigzag Herons, Long-winged Harrier, 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: The Pantanal & Interior Brazil 2015 www.birdquest-tours.com White-browed Hawk, Onate Hawk-Eagle, Harpy Eagle, Red-legged Seriema, Sunbittern, Sungrebe, Rufous- sided, Grey-breasted, Yellow-breasted and Ocellated Crakes, Pheasant and Black-bellied Cuckoos, Crested Owl, -

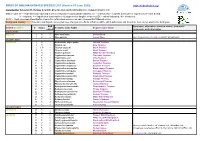

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4Th to 25Th September 2016

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4th to 25th September 2016 Marañón Crescentchest by Dubi Shapiro This tour just gets better and better. This year the 7 participants, Rob and Baldomero enjoyed a bird filled trip that found 723 species of birds. We had particular success with some tricky groups, finding 12 Rails and Crakes (all but 1 being seen!), 11 Antpittas (8 seen), 90 Tanagers and allies, 71 Hummingbirds, 95 Flycatchers. We also found many of the iconic endemic species of Northern Peru, such as White-winged Guan, Peruvian Plantcutter, Marañón Crescentchest, Marvellous Spatuletail, Pale-billed Antpitta, Long-whiskered Owlet, Royal Sunangel, Koepcke’s Hermit, Ash-throated RBL Northern Peru Trip Report 2016 2 Antwren, Koepcke’s Screech Owl, Yellow-faced Parrotlet, Grey-bellied Comet and 3 species of Inca Finch. We also found more widely distributed, but always special, species like Andean Condor, King Vulture, Agami Heron and Long-tailed Potoo on what was a very successful tour. Top 10 Birds 1. Marañón Crescentchest 2. Spotted Rail 3. Stygian Owl 4. Ash-throated Antwren 5. Stripe-headed Antpitta 6. Ochre-fronted Antpitta 7. Grey-bellied Comet 8. Long-tailed Potoo 9. Jelski’s Chat-Tyrant 10. = Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Yellow-breasted Brush Finch You know it has been a good tour when neither Marvellous Spatuletail nor Long-whiskered Owlet make the top 10 of birds seen! Day 1: 4 September: Pacific coast and Chaparri Upon meeting, we headed straight towards the coast and birded the fields near Monsefue, quickly finding Coastal Miner. Our main quarry proved trickier and we had to scan a lot of fields before eventually finding a distant flock of Tawny-throated Dotterel; we walked closer, getting nice looks at a flock of 24 of the near-endemic pallidus subspecies of this cracking shorebird. -

Download This PDF File

ISSN (impresso/printed) 0103-5657 ISSN (on-line) 2178-7875 Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia Volume 21 / Issue 21 Número 2 / Number 2 www.ararajuba.org.br/sbo/ararajuba/revbrasorn.htm Junho 2013 / June 2013 Publicada pela / Published by the Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia / Brazilian Ornithological Society Belém - PA ISSN (impresso/printed) 0103-5657 ISSN (on-line) 2178-7875 Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia EDITOR / EDITOR IN CHIEF Alexandre Aleixo, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi / Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação, Belém, PA. E-mail: [email protected] Revista Brasileira SECRETARIA DE APOIO À EDITORAÇÃO / MANAGING OFFICE Fabíola Poletto – Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais Bianca Darski Silva - Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Carla Haisler Sardelli - Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi EDITORES DE ÁREA / ASSOCIATE EDITORS Comportamento / Behavior:Artigos publicados na RevistaCarlos Br asileiA. Bianchi,ra de Universidade Ornitologia Federal são de indexadosGoiás, Goiânia, por: GO Biological Abstract, Scopus (Biobase,Ivan Sazima, Geobase Universidade e EM EstadualBiology) de Campinas e Zoological, Campinas, R ecoSP rd. Cristiano Schetini de Azevedo, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, MG de Ornitologia MConservaçãoanuscripts / Conservation:published by Revista Brasileira deAlexander Ornitologia C. Lees, Museuare c oParaensevered Emílioby the Goeldi foll, Belém,owing PA indexing databases: Ecologia B/ Ecology:iological Abstracts, Scopus (Biobase,Leandro Geobase, Bugoni, and Universidade EMB iology),Federal do -

Arboreal Perching Birds

Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries Standards For Arboreal/Perching Bird Sanctuaries Version: December 2019 ©2012 Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries – Standards for Arboreal/Perching Bird Sanctuaries Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 GFAS PRINCIPLES ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 ANIMALS COVERED BY THESE STANDARDS ................................................................................................. 1 ARBOREAL/PERCHING BIRD STANDARDS .................................................................................................... 3 ARBOREAL/PERCHING BIRD HOUSING ............................................................. 3 H-1. Types of Space and Size .................................................................................................................................................... 3 H-2. Containment ................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 H-3. Ground and Plantings ........................................................................................................................................................... 7 H-4. Gates and Doors ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club Volume 135 No. 1 March 2015 FORTHCOMING MEETINGS See also BOC website: http://www.boc-online.org BOC MEETINGS are open to all, not just BOC members, and are free. Evening meetings are in an upstairs room at Te Barley Mow, 104 Horseferry Road, Westminster, London SW1P 2EE. Te nearest Tube stations are Victoria and St James’s Park; and the 507 bus, which runs from Victoria to Waterloo, stops nearby. For maps, see http://www.markettaverns.co.uk/the_barley_mow.html or ask the Chairman for directions. The cash bar opens at 6.00 pm and those who wish to eat after the meeting can place an order. The talk will start at 6.30 pm and, with questions, will last c.1 hour. It would be very helpful if those intending to come can notify the Chairman no later than the day before the meeting. Tuesday 10 March 2015—6.30 pm—Dr Clemency Fisher—A jigsaw puzzle with many pieces missing: reconstructing a 19th-century bird collection Abstract: In 1838–45, ‘The Birdman’ John Gould’s assistant, John Gilbert, collected more than 8% of the bird and mammal species of Australia for the first time. He sent hundreds of specimens back to Gould, who used many of them to describe new species and then recouped his outlay by selling the specimens to contacts all over the world. Some of the new owners removed Gilbert’s labels and mounted their specimens for display; some put new ones on, or placed their specimens into poor storage where both specimen and label were eaten by beetle larvae.