Cochran, Lee W. TITLE Visual Iiteracy--The Last Word

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent Vs. Sign to a Label: Artist's Point of View

Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent vs. Sign to a Label: Artist’s Point of View Sampo Winberg Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in International Business 2018 Abstract Date 22.5.2018 Author(s) Sampo Winberg Degree programme International Business Report/thesis title Number of pages Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent vs. Sign to and appendix pages a Label: Artist’s Point of View 58 + 6 The mark of an artist making it in music industry, throughout its relatively short history, has always been a record deal. It is a ticket to fame and seen as the only way to make a living with your music. Most artist would accept a record deal without hesitating. Being an artist myself I fall into the same category, at least before conducting this research. As we know record labels tend to take a decent chunk of artists’ revenues. Goal of this the- sis is to find out ways how a modern-day artist makes money, and can it be done so that it would be better to remain as an independent artist. What is the difference in volume that artist needs without a label vs. with a label? Can you get enough exposure and make enough money that you can manage without a record label? Technology has been and still is the single most important thing when it comes to the evo- lution of the music industry. New innovations are made possible by constant technological development and they’ve revolutionized the industry many times. First it was vinyl, then CD, MTV, Napster, iTunes, Spotify etc. -

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

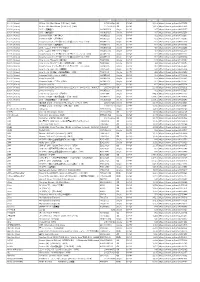

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Alumnews09-10

College of Letters & Science University D EPARTMENT of of California Berkeley MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter December 2010 NOTE FROM THE CHAIR “Smart people and lots of hair—just what I expected of Berkeley,” was Rufus 1–3 Events, Celebrations, Wainwright’s summation at the end of his visit to our department. In town for the San 1 Francisco Symphony’s performance of his song cycle, Wainwright engaged in a lively Visitors exchange with a cross-section of Music students in the Albert Elkus Room. Wainwright is just one of the many guests who have contributed to the vibrant intellectual community 1, 9, 14–15 Heavy Lifters of the Department of Music over the past few years. Visiting from Italy, Israel, and the UK, Pedro Memelsdorf, Edwin Seroussi, and Peter Franklin have taught courses and delivered public 4–5 Faculty Update • Pianos lectures during their semester-long residencies and a series of shorter visits by leading composers from North 4 America, Europe, and Japan is currently underway. Our students and faculty have many accomplishments to be proud of—concerts and compositions, papers and publications—as you will see throughout this 6–8, 10 Alumni News newsletter, in which we also mourn the recent loss of several dear members of our community. The 6 Department of Music has endured the toughest financial crisis in the university’s history undiminished. 6–7 In Memoriam Although the end of that crisis is not yet in sight, we continue to strive to improve in our many areas of activity. Please enjoy this newsletter and turn to our redesigned website, which debuted last fall, for the latest 8–9 Fundraising Update, news of the Department of Music. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Change Is Not a Dirty Word • Station Collaborations

THE MAGAZINE OF THE CBAA COLLA BORA GOVERNANCEI FORO COMMUNITY RADIO BOARDSN T CHANGE IS NOT A DIRTY WORD • STATION COLLABORATIONS AUGUST 2016 “Loved the networking and meeting “Very informative, entertaining, “This conference was friendly, up old friends, making new friends insightful and inspiring weekend... engaging and informative and learning about other stations.” Bloody fantastic...” ...loved it.” Nancy Jo Falcone, Phil Ruck, Gerry ‘G-Man’ Lyons, 99.9 Bay FM 3MDR Mountain District Radio CAAMA Radio LEARN MEET SHARE from sector your fellow your knowledge and industry leaders passionate community and stories broadcasters 8 20 10 AUGUST 2016 14 4 President's Column ......................................................................................2 CONTENTS CBAA Update .................................................................................................3 Australian Community Radio swings on International Jazz Day .............................................................4 Behind the Mic: Ella Scott ...........................................................................7 Let’s get together: Nambucca Valley Radio and Braidwood Community Radio ................8 Change is not a dirty word Holly Ransom Interview ............................................................................ 10 7 Keys Areas for Governance of Community Broadcasting Boards .......................................................12 Amrap Q&A ................................................................................................. -

Trung Tâm Điều Trị Suy Giãn Tĩnh Mạch

Thuong Mai Week-End CUOÁI TUAÀN 1877 February 15, 2020 10515 Harwin Dr., Suite 100-120, Houston, TX 77036 (goùc Harwin Dr. @ Corporate Dr.) Tel: 713-777-4900 * 713-777-8438 * 713-777-VIET * 713-777-2012 * Fax.: 713-777-4848 Website: thevietnampost.com * E-mail: [email protected] Chuùng toâi chuyeân ñaûm traùch TRUNG TÂM ĐIỀU TRỊ SUY GIÃN TĨNH MẠCH moïi dòch vuï BAÛO HIEÅM: XE HÔI - NHAØ CÖÛA - NHAÂN THOÏ TRIEÄU CHÖÙNG & CAÙCH ÑIEÀU TRÒ GIAÕN TÓNH MAÏCH Ñieàu Trò Suy Giaõn Tónh Maïch THÖÔNG MAÏI - IRA - MUTUAL FUNDS CAÙC GIÃN TĨNH MẠCH SƯNG PHÙ DA SẠM MÀU LỞ LOÉT Ñieàu Trò Thoaùt Vò TRIEÄU SHAWN XUAÂN NGUYEÃN, LUTCF CHÖÙNG Phaãu Thuaät Tuùi Maät 10039 Bissonnet, Suite 226 GIAÕN Houston, TX 77036 (713)988-0752 TÓNH Phaãu Thuaät Daï Daøy, Tröïc Traøng HARRY DAO MAÏCH Phaãu Thuaät Tuyeán Giaùp INSURANCE Nếu bạn có cảm giác chân nóng, ngứa, nổi gân xanh, dễ mệt mỏi, BAÛO HIEÅM TOÁT, GIAÙ CAÛ NHEÏ NHAØNG áp lực, co thắt, thay đổi màu da, sưng, khô, loét, v.v ... ÑIEÀU TRÒ BAÈNG PHÖÔNG PHAÙP NOÄI SOI OÅ BUÏNG Đừng chờ đợi, hãy đến gặp chúng tôi ngay! XE - NHAØ - THÖÔNG MAÏI Laøm giaûm ñau vaø ruùt ngaén thôøi gian hoài phuïc NHAÂN THOÏ - SÖÙC KHOÛE NHÖÕNG LÔÏI ÍCH CUÛA ÑIEÀU TRÒ SUY GIAÕN TÓNH MAÏCH Laøm seïo ít hôn sau phaãu thuaät INCOME TAX, GIAÁY TÔØ XE, GIAÛI TICKET, DI TRUÙ, HOÄ CHIEÁU Gaây meâ cuïc boä ngay taïi vaên phoøng ÑOÄC THAÂN COÂNG HAØM Ñi laïi ngay sau khi ñieàu trò ÑIEÀU TRÒ SUY GIAÕN TÓNH MAÏCH HAÀU HEÁT BILL OF SALE Khoâng ñeå laïi seïo hay söng phuø ÑEÀU ÑÖÔÏC CAÙC COÂNG TY BAÛO HIEÅM HOÃ TRÔÏ 281-933-8300 8300 W. -

Being Chiefly Reports on New Music and Opera (1987-88)

A CRITICAL PORTFOLIO: REPORTS ON NEW MUSIC AND OPERA A CRITICAL PORTFOLIO: BEING CHIEFLY REPORTS ON NEW MUSIC AND OPERA (1987-88) BY A CRITIC LIVING IN HAMILTON, ONTARIO By ALAN RICHARD GASSER, B. M., M. M. EssayAccompanying a Collection of Musical Criticisms Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University Copyright (§) 1988 by Alan Richard Gasser MASTER OF ARTS (1988) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Music Criticism) Hamilton, Ontario TITI..E: A Critical Portfolio: Being Chiefly Reports on New Music and Opera (1987-88) by a Critic Living in Hamilton, Ontarj[o AUTHOR: Alan Richard Gasser, B.M. (College of Wooster) M.M. (University of Minnesota) SUPERVISOR: Mr. William Littler (external) Professor Paul Rapoport (internal) NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 151 Ii ABSTRACT The critical portfolio here collected was written under the guidance of Mr. William Littler, music critic of the Toronto Star. ][t is primarily an idiosyncratic account of the new music concerts and opera productions in the Toronto and Hamilton area between June, 1987 and June, 1988. Canadian composers, performers and performings organizations are mentioned prominently, though significant concerts and operas from elsewhere lend breadth and depth to the coverage. In an introductory essay, the thorny matter of using words to write about music is dealt with obliquely, through a discussion of the organization of the separate reports into a portfolio. The overall form of the portfolio is a literary one which alludes to traditional symphonic forms. A short statement of the author's critical predilections serves as the critical creed in which these separate reports have a common origin. -

Dutroux Demande À Êtrelibérédeprison

! auté e… mmun omment EN Co articipe,c MOI change,p fluence,é Réagis, in Dutroux demande à N°2765 JEUDI être libéré de prison 17 OCTOBRE 2019 Luxembourg 6-7 Marc Dutroux peut-il se réinsérer dans la emprisonné depuis 23 ans. Son avocat dé- société? La justice belge rouvre aujourd'hui peint l'audience du jour comme «une étape Mathilde et Stéphanie à la rencontre des petits ce dossier criminel ultra sensible pour exa- obligée dans le parcours» vers cette libéra- miner une demande d'expertise psychiatri- tion conditionnelle qu'il espère décrocher à que déposée par les avocats du pédophile l'horizon 2021. PAGE 2 Quand les séries dictent la mode Tendances 23 Europa-Park s'amuse à faire peur pour Halloween Sports 33 Des cadres dynamiques boxent sur une péniche Météo 36 Costume trois pièces et casquette gavroche, il faudra au moins ça pour ressembler aux gangsters de la série «Peaky Blinders». MATIN APRÈS-MIDI LONDRES Plus encore que les manne- de la mode. Au point de devenir succès se traduit par une hausse quins, les acteurs ou les influen- des modèles de vie et de style. En des ventes de vêtements ou acces- 12° 15° ceurs, les personnages des séries Grande-Bretagne, l'apparition soires portés par leurs populaires sont devenus de véritables icônes d'une nouvelle saison de séries à personnages. PAGE 14 PUB MANTEL 15% CITABEL LEUDELANGE IS OPEN 20 OCTOBER WEEK-END on Clothing 19-20 october >> 14h -18h 2 Actu JEUDI 17 OCTOBRE 2019 / LESSENTIEL.LU Le laboratoire de l'horreur Vite lu HAMBOURG Dernière en date parmi les vidéos- LPT, l'un des plus grands laboratoires d'expéri- chocs prouvant des cas de cruauté envers les mentations pharmaceutiques et toxicologiques animaux, une séquence tournée en Allemagne d'Allemagne, près de Hambourg. -

Reality Check Ar, Vr and Sr Meet the Music Industry Introduction

REALITY CHECK AR, VR AND SR MEET THE MUSIC INDUSTRY INTRODUCTION Thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic, the real world has been an unsettling place for much of 2020. That partly explains the renewed appeal of technologies like augmented and virtual reality, which let people escape into worlds of colourful Pokémon; use a comical camera filter to cheer themselves up; get indoor exercise by slashing blocks with a pair of imaginary sabers; or even have a bittersweet memory of real-world concerts by watching one from the moshpit in VR. These technologies are more than just an escape, however: they are DEFINITIONS tools that artists and labels can use to create fun, engaging and Augmented Reality sometimes even jaw-dropping new experiences for fans. Not just for Superimposes digital the sake of the technology itself either, but in service of the music, and content and information on helping those artists to grow their audiences. our view of the real world, be it through a smartphone This report, which follows the BPI / Music Ally insight session that was screen or AR glasses. held online on 3 December 2020, explores what’s being done now with Virtual Reality augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) by labels and artists, but Fully immerses us in virtual also looks forward to what might come next, and what it will mean for spaces, using our gaze our industry. There is also a third reality to think about: synthetic reality and our hand gestures to interact with while wearing (SR), and the emerging space of avatar music stars, whether based on a virtual reality headset. -

Raymonde Reveals His Bella-Vision

CoverV4_cover template 04/09/2012 17:44 Page 1 3 6 9 776669 776136 THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC www.musicweek.com 07.09.12 £5.15 NEWS ANALYSIS FEATURE 03 14 17 Peers, associates and Music Week takes an in-depth look into How the PR sector is coping fans remember the the UK’s most-streamed tracks from the with doing more with great Hal David first half of the calendar year less resource than ever BMG TELLS BRUSSELS: LET US COMPETE WITH WARNER, SONY AND UNIVERSAL Raymonde reveals his Major ambitions Bella-vision LABELS want to create a genuinely new I BY TIM INGHAM competitive environment?” He claimed potential earnings MG is ready to take on of artists switching to BMG's the mantle of the masters model could be three Brecorded music industry’s times that of a conventional deal. fourth major if it can successfully Masuch said that “if assets purchase juicy assets related to which fall out of the Universal- Universal’s buyout of EMI. EMI deal end up with the two The rights management other majors, the best you can company is understood to be hope for is more of the same”. keen to acquire divested record He explained: “If you look at catalogues such as Virgin Records the history of the industry over or Parlophone. A final behind- the past 30 years, every integration Bella Union founder Simon closed-doors decision from EC of an independent label into a Raymonde is sick of his artists regulators on Universal’s £1.2bn major resulted in a new combined not getting opportunities on UK bid is expected this week. -

2015-16 Season It's About Tim E!

16 SE 5- AS 1 O 0 N 2 I T ! ’ S E A I M B O U T T - 1 6 S E 5 A S TThehe 2012015/165/16 season exexploresplores mumusicsic as a 1 O ““timetime art”, memormemoryy and nostanostalgia,lgia, the lelegacygacy ooff 0 N MaudMaud Powell, and the ElElgingin WaWatchtch FactoryFactory Band, c. 18921892.. 2 MONUMENTMONUMENTAL FEAFEATURINGTURING VIOLINISTVIOLINIST RACHELRACHEL BARTONBARTON PINE AT 7:30PM7:30PM SundaySunday, November 8, 2015, 2:00, 4:30, and 7:307:30 ppmm ECC Arts CCenterenter,, BlizzardBlizzard Theatre ELGIN YOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CMICMI CONCERTSCONCERTS Randal Swiggum, Artistic Director Sunday, November 22, 2015 OPEN HOUSE EVENTS Sunday, Feb 28, 2016 Sunday, April 17, 2016 TIMEPIECES WITH GUEST CONDUCTOR DANIEL BOICO CITY OF TIME Sunday, March 13, 2016, 2:00, 4:30, and 7:30 pm A 40TH ANNIVERSARY GALA CELEBRATION ECC Arts Center, Blizzard Theatre MAY 15, 2016 RESONANCE WITH GRAMMY-WINNING EIGHTH BLACKBIRD HEMMENS CULTURAL CENTER, ELGIN, ILLINOIS Saturday, April 16, 2016, 7:00 pm ECC Arts Center, Blizzard Theatre I CMI CONCERTS T ! Sunday, April 24, 2016 ’ E S M CITY OF TIME A I A 40TH ANNIVERSARY REUNION & GALA CELEBRATION B T Sunday, May 15, 2016, 3:00 and 7:00 pm O U T The Hemmens Cultural Center, Elgin AUDITIONS AUDITIONS FOR THE 2016-17 SEASON EYSO.ORG June 2-5, 2016 Connect tickets:847.622.0300 or http://tickets.elgin.edu THE ELGIN YOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA IS AN IN-RESIDENCEIN-RESIDENCE ENSEMBLENSEMBLEEA ATTT THEHE ECCECCA ARRTTSS CENTCENTERER 2008 2000, 2007 2005, 2015 2001 CONDUCTOR YOUTH ORCHESTRA PROGRAMMING ELGIN IMAGE OF THE YEAR OF THE YEAR OF THE YEAR AWARD EYELGIN YOUTH SYMPHONYSO ORCHESTRA Dear Friends, The Elgin Youth Symphony Orchestra’s 40th anniversary season is drawing to a close. -

LOIZEAUX SLATE WINS Mostult-NOMINATIQNS

THE WEATHER Try Fair today and tomorrow THE HILLSIDE TIMES ‘ \ F or Your Next Order Of PRINTING VOL. x n . NO. 581 PRICE FIVE CENTS Don’t Mention 2n d N u r s e Victorious Here It F o r C h i l d LOIZEAUX SLATE WINS lignite cnf.^nai over the .political situation. Tuesday rJght. He rushed Into th® office cet ‘ fdwBIBSV Howard J. 8ioy, ob H y g i e n e MOSTUlt-NOMINATIQNS. tained primary 'flection" returns rbr County ConHHittee Makeup In- ■ several' districts and telephoned ’R e Hale and Schnabel Have Little publican headquarters.” He read off Board of Health Approves Project Doubt, Although IndicatiotLS Difficulty F or Township Com- 1—the- distr-iet- returns—and . then asked Arranged by State Depart- Are For Loizeaux Local Men Nominated jrhittee; Fort Wins Here to talk to John J. Molson, head o£ the m enf of Health Loizeaux organization, with which LufL- SEVERAL EXPECTEDTO— EASCjQE r u n s s e c o n d •TB’gn is affiliated.- He learneff only-then PRE-SCHOOL CHILDREN ASPIRE TO CHAIRMAN ON ASSEMBLY TICKET -t'.mr. l-.a had given' the -rival daap.-flw TOO NUMEROUS FOR ONE results, it aepefldinm whiclrtslda—of- Tuesday’s \ primary ' erection - -the lence yoirare when you say ’'Re Aeeebtanao—ef- a pvdast » « » » .< the change o f pan of the ir.sinber^hl’y Btesy-virtorite^tor Township teemen Benjamin Hale and Harry al publican headquarters.” through th e. State .Department cf of the .Republican county committee of ■the township but apparently left tho "Srlmabel over—the—thli’d' Republlean liseglth to add smother nurse to; the ■candidate, PYank J.