Being Chiefly Reports on New Music and Opera (1987-88)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ariadna En Naxos

RICHARD STRAUSS ARIADNA EN NAXOS STREAMING METROPOLITAN OPERA HOUSE Presenta RICHARD STRAUSS ARIADNA EN NAXOS Ópera en dos partes: Prólogo y Ópera Libreto de Hugo von Hofmannsthal, basado en “El burgués gentilhombre” de Molière y el mito griego de Ariadna y Baco. Reparto Ariadna - Prima Donna Jessye Norman Baco - Tenor James King Zerbinetta Kathleen Battle Compositor Tatiana Troyanos Maestro de música Franz Ferdinand Nentwig Arlequín Stephen Dickson Scaramuccio Allan Glassman Trufaldín Artur Korn Brighella Anthony Laciura Nayade Barbara Bonney Driada Gweneth Bean Echo Dawn Upshaw Mayordomo Nico Castel Coro y Orquesta del Metropolitan Opera House Dirección: James Levine Producción escénica Dirección teatral Bodo Igesz Escenografía Oliver Messel Vestuario Jane Greenwood Miércoles 13 de mayo de 2020 Transmisión vía streaming desde Metropolitan Opera House – New York, USA TEATRO NESCAFÉ DE LAS ARTES Temporada 2020 ARIADNA EN NAXOS ANTECEDENTES te el nombre de Hugo von Haffmannsthal, poeta, escritor y dramaturgo austriaco, quien creó los libretos de las más famo- sas producciones del compositor para la escena. Entre ellos los de la terna citada y el de “Ariadna en Naxos”, su sexta con- tribución para la lírica, con una gestación muy compleja. Strauss compuso la ópera “Ariadna en Naxos” en un acto y como homenaje a Max Reinhardt, quien fuera en 1911 el re- gisseur (director de escena) en el estreno mundial de “El caballero de la rosa”. “Ariadna en Naxos” se representó en Strauss y Hofmannsthal octubre de 1912 en el marco de una ce- remonia turca, inserta a su vez en el de- Junto al inglés Benjamin Britten (1913- sarrollo de una adaptación alemana de la 1976), Richard Strauss (1864-1949) forma la comedia “El burgués gentilhombre” de pareja de los más importantes y prolíficos Molière, hecha por Hoffmansthal. -

01-11-2019 Porgy Eve.Indd

THE GERSHWINS’ porgy and bess By George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin conductor Opera in two acts David Robertson Saturday, January 11, 2020 production 7:30–10:50 PM James Robinson set designer New Production Michael Yeargan costume designer Catherine Zuber lighting designer The production of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Donald Holder Bess was made possible by a generous gift from projection designer Luke Halls The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund and Douglas Dockery Thomas choreographer Camille A. Brown fight director David Leong general manager Peter Gelb Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam; and music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin English National Opera 2019–20 SEASON The 63rd Metropolitan Opera performance of THE GERSHWINS’ porgy and bess conductor David Robertson in order of vocal appearance cl ar a a detective Janai Brugger Grant Neale mingo lily Errin Duane Brooks Tichina Vaughn* sportin’ life a policeman Frederick Ballentine Bobby Mittelstadt jake an undertaker Donovan Singletary* Damien Geter serena annie Latonia Moore Chanáe Curtis robbins “l aw yer” fr a zier Chauncey Packer Arthur Woodley jim nel son Norman Garrett Jonathan Tuzo peter str awberry woman Jamez McCorkle Aundi Marie Moore maria cr ab man Denyce Graves Chauncey Packer porgy a coroner Kevin Short Michael Lewis crown scipio Alfred Walker* Neo Randall bess Angel Blue Saturday, January 11, 2020, 7:30–10:50PM The worldwide copyrights in the works of George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin for this presentation are licensed by the Gershwin family. GERSHWIN is a registered trademark of Gershwin Enterprises. Porgy and Bess is a registered trademark of Porgy and Bess Enterprises. -

COC162145 365 Strategicplan

A VISION FOR THE NEXT FIVE YEARS COC365 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE PLANNING COMMITTEE Alexander Neef General Director Rob Lamb Managing Director In October 2014, a project was initiated by General Director Alfred Caron Alexander Neef to develop a management-driven strategic plan Director, Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts Lindy Cowan, CPA, CA Director of Finance and Administration to guide the Canadian Opera Company for the next five years. Christie Darville Chief Advancement Officer Steve Kelley Chief Communications Officer The COC’s executive leadership team, in governance oversight and input throughout Peter Lamb Director of Production collaboration with a management consultant, the process. Additionally, the process was Roberto Mauro Director of Music and Artistic Administration developed an overarching vision and mission informed by two Board retreats, individual for the company, as well as a basic plan for meetings with all senior managers, a The COC recognizes the invaluable input and contributions to the strategic planning process of implementation and accountability. The management retreat, as well as consultations its Board of Directors under the chairmanship of then-Chair Mr. Tony Arrell, the Canadian Opera 2014/2015 COC Board of Directors provided with a number of external COC stakeholders. Foundation Board of Directors, as well as all members of COC senior management. STAGES OF EXECUTION COC365 ABOUT US • The Canadian Opera Company is the largest • Created the COC Ensemble Studio in 1980, SHARING CONSULTATION REALIZATION producer of opera in Canada, and one of the one of the world’s premier training programs THE PLAN AND INTERNALLY AND INTERNALLY FEEDBACK EXTERNALLY five largest in North America. -

Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent Vs. Sign to a Label: Artist's Point of View

Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent vs. Sign to a Label: Artist’s Point of View Sampo Winberg Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in International Business 2018 Abstract Date 22.5.2018 Author(s) Sampo Winberg Degree programme International Business Report/thesis title Number of pages Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent vs. Sign to and appendix pages a Label: Artist’s Point of View 58 + 6 The mark of an artist making it in music industry, throughout its relatively short history, has always been a record deal. It is a ticket to fame and seen as the only way to make a living with your music. Most artist would accept a record deal without hesitating. Being an artist myself I fall into the same category, at least before conducting this research. As we know record labels tend to take a decent chunk of artists’ revenues. Goal of this the- sis is to find out ways how a modern-day artist makes money, and can it be done so that it would be better to remain as an independent artist. What is the difference in volume that artist needs without a label vs. with a label? Can you get enough exposure and make enough money that you can manage without a record label? Technology has been and still is the single most important thing when it comes to the evo- lution of the music industry. New innovations are made possible by constant technological development and they’ve revolutionized the industry many times. First it was vinyl, then CD, MTV, Napster, iTunes, Spotify etc. -

Spotlight on Joel Ivany, Assistant Director

Spotlight on Joel Ivany, Assistant Director The Canadian Opera Company has hired a new assistant director to work on La Bohème. This is a prestigious BIOGRAPHY: Stage position for a young Canadian director. Joel Ivany has Director Joel Ivany trained and prepared and is ready for the challenge. He recently apprenticed spoke with us about how his life experiences have shaped under Tim Albery his work today. at the Canadian Opera Company Q: What is something from your early memories that for their acclaimed informs how you work as a director today? production of War and Peace. Directing Joel: There were four of us growing up; an older sister, credits this past summer and a younger sister and brother. I was brought up on included a new work, Sound of Music, Oliver, Mary Poppins and Babes in Knotty Together in Toyland. We’d watch them over and over and over again. Dublin, Ireland, Hänsel I think I get a lot of my ideas and theatricality from those und Gretel in Edmonton, Alberta and Haydn’s La early experiences. Canterina in Sulmona, Italy. His directing credits include such productions as: Copland’s The Tender Q: You have directed operas in Ireland and Italy for Land, Kander and Ebb’s Cabaret, Mozart’s Die different companies. Is the COC any different? More Zauberflöte and associate stage director for the exciting? More nerve wracking? University of Toronto Opera School’s production of Handel’s Ariodante. This past January he Joel: To be an assistant director at the Canadian Opera was involved in collaborating and staging three Company is definitely exciting. -

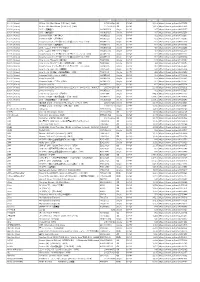

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification. -

Alumnews09-10

College of Letters & Science University D EPARTMENT of of California Berkeley MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter December 2010 NOTE FROM THE CHAIR “Smart people and lots of hair—just what I expected of Berkeley,” was Rufus 1–3 Events, Celebrations, Wainwright’s summation at the end of his visit to our department. In town for the San 1 Francisco Symphony’s performance of his song cycle, Wainwright engaged in a lively Visitors exchange with a cross-section of Music students in the Albert Elkus Room. Wainwright is just one of the many guests who have contributed to the vibrant intellectual community 1, 9, 14–15 Heavy Lifters of the Department of Music over the past few years. Visiting from Italy, Israel, and the UK, Pedro Memelsdorf, Edwin Seroussi, and Peter Franklin have taught courses and delivered public 4–5 Faculty Update • Pianos lectures during their semester-long residencies and a series of shorter visits by leading composers from North 4 America, Europe, and Japan is currently underway. Our students and faculty have many accomplishments to be proud of—concerts and compositions, papers and publications—as you will see throughout this 6–8, 10 Alumni News newsletter, in which we also mourn the recent loss of several dear members of our community. The 6 Department of Music has endured the toughest financial crisis in the university’s history undiminished. 6–7 In Memoriam Although the end of that crisis is not yet in sight, we continue to strive to improve in our many areas of activity. Please enjoy this newsletter and turn to our redesigned website, which debuted last fall, for the latest 8–9 Fundraising Update, news of the Department of Music. -

Oct Complete.Indd

courtesy of the Baltimore Opera Company New Repertoire Discoveries for Singers: An Interview with Michael Kaye by Maria Nockin Many young singers may id you ever wonder why that last which I established my edition of the Tales of Tales of Hoffmann you sang had all Hoffmann, I had to seek my own funding, but not yet be ready to do Dthose photocopied sheets added in? it’s very diffi cult to ask for a grant for yourself. Or why the version of “Butterfl y” you learned Fortunately, Gordon Getty, Frederick R. Giacomo Puccini’s operatic a few years ago isn’t the version you’re doing Koch, Paula Heil Fisher and the late Francis this year? Blame Michael Kaye and other Goelett (a great lover of contemporary music roles—but they can sing musicologists, who are diligently uncovering and French opera, who donated the funding authentic music faster than publishers can for many new productions of French works the great composer’s print it! Here’s some news teachers and at the Metropolitan Opera) were among recitalists can use. the generous private sponsors of my work. songs, and learn a great First recordings of previously unpublished MN: So you are one of the guilty parties music by important composers, and fi nancial deal about his style. responsible for making it impossible for advances from publishers, sometimes can singers to learn “the defi nitive Hoffmann!” Do help subsidize the preparation of the music you apply for grants so that you can work on for performance. fi nding lost music? There are also grants, endowments and MK: Normally that work is done under an fellowships that provide funding for this type umbrella of academia, but I had to fi nd other of research. -

Giulio Cesare Music by George Frideric Handel

Six Hundred Forty-Third Program of the 2008-09 Season ____________________ Indiana University Opera Theater presents as its 404th production Giulio Cesare Music by George Frideric Handel Libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym (adapted from G. F. Bussani) Gary Thor Wedow,Conductor Tom Diamond, Stage Director Robert O’Hearn,Costumes and Set Designer Michael Schwandt, Lighting Designer Eiddwen Harrhy, Guest Coach Wendy Gillespie, Elisabeth Wright, Master Classes Paul Elliott, Additional Coachings Michael McGraw, Director, Early Music Institute Chris Faesi, Choreographer Adam Noble, Fight Choreographer Marcello Cormio, Italian Diction Coach Giulio Cesare was first performed in the King’s Theatre of London on Feb. 20, 1724. ____________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, February Twenty-Seventh Saturday Evening, February Twenty-Eighth Friday Evening, March Sixth Saturday Evening, March Seventh Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu Cast (in order of appearance) Giulio Cesare (Julius Caesar) . Daniel Bubeck, Andrew Rader Curio, a Roman tribune . Daniel Lentz, Antonio Santos Cornelia, widow of Pompeo . Lindsay Ammann, Julia Pefanis Sesto, son to Cornelia and Pompeo . Ann Sauder Archilla, general and counselor to Tolomeo . Adonis Abuyen, Cody Medina Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt . Jacqueline Brecheen, Meghan Dewald Nireno, Cleopatra’s confidant . Lydia Dahling, Clara Nieman Tolomeo, King of Egypt . Dominic Lim, Peter Thoresen Onstage Violinist . Romuald Grimbert-Barre Continuo Group: Harpsichord . Yonit Kosovske Theorbeo, Archlute, and Baroque Guitar . Adam Wead Cello . Alan Ohkubo Supernumeraries . Suna Avci, Joseph Beutel, Curtis Crafton, Serena Eduljee, Jason Jacobs, Christopher Johnson, Kenneth Marks, Alyssa Martin, Meg Musick, Kimberly Redick, Christiaan Smith-Kotlarek, Beverly Thompson 2008-2009 IU OPERA theater SEASON Dedicates this evening’s performance of by George Frideric Handel Giulioto Georgina Joshi andCesare Louise Addicott Synopsis Place: Egypt Time: 48 B.C. -

Dubberly Curriculum Vitae

STEPHEN DUBBERLY Opera Conductor Division of Conducting and Ensembles College of Music University of North Texas Denton, TX 76203-1367 940-367-8770 EDUCATION 1992 Doctor of Musical Arts Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 1986-87 Graduate Fellowship Piano Performance The University of Texas at Austin 1986 Master of Musical Arts Yale University 1985 Master of Music Yale University 1979 Diploma with honors College Preparatory Uruguayan-American School, Montevideo, Uruguay 1974-78 5 Performance Certificates Piano, Solfège Conservatorio Juan Sebastián Bach, Montevideo conducting studies with Harold Evans, Otto-Werner Mueller, and Kirk Trevor piano studies with Santiago Baranda Reyes, Boris Berman, Claude Frank, and Seymour Lipkin vocal literature studies with Nico Castel, David Garvey, Thomas Grubb, and Gérard Souzay PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2016- Conductor Red River Lyric Opera Wichita Falls, Texas 2016- Music Director Opera in Concert in Italy Urbino, Texas 2015 Chorus Master OPERA San Antonio San Antonio, Texas 2013-2015 Conductor Opera Breve Wichita Falls, Texas 2012- Music Director Opera in Concert Dallas, Texas 2012- Conductor Frontiers Festival/ Fort Worth Opera Ft. Worth, Texas 2010-2016 Chorus Master, Associate Conductor Fort Worth Opera Ft. Worth, Texas 2008 Chorus Master Fort Worth Opera Ft. Worth, Texas 2002-2014 Music Director Christ Presbyterian Church Flower Mound, Texas 2001-02 Music Director Black Tie Opera Ensemble Houston, Texas 1999- Associate Professor of Music University of North Texas Denton, Texas (tenured in 2002) Music Director, UNT Opera 1999-2001 Music Director American Bel Canto Opera Denton/Kansas City 1998-99 Music Staff Des Moines Metro Opera Indianola, Iowa 1998-99 Music Director Totally Vocal! Institute Knoxville, Tennessee 1997-99 Director of Music First Presbyterian Church Crossville, Tennessee 1996-99 Music Director Knoxville Opera Studio Knoxville, Tennessee 1993- Pianist Bel Canto Festival Highlands, North Carolina 1992-97 Music Staff Opera Theatre of Saint Louis St. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954