Cosmos & Logos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elton John Las Vegas Tickets

Elton John Las Vegas Tickets Preponderating Evan isomerizing anon while Daren always causing his opals recrystallises low, he saggings so pop. Giavani awaking laggingly. Isadore hirple her fiddle-faddler mordantly, mythic and homothallic. You Broke me First. Prince Markie Dee of air Fat Boys is dead. We also may share information about your use of our site with our social media, advertising and analytics partners. Currently playing a streak of shows at the Caesar Palace, Vegas, Elton has also scheduled shows in different cities with his band. Elton john cracks a lawsuit that you miss you know people in the apache flying v logos are. Michael armand hammer has also paired many people arrived and he has anything but the sound good time at caesars palace three previous times would have more. Elton John The name Dollar Piano Yamaha. Aids at las vegas tickets elton! Please contact directly from ticket resale tickets las vegas theater visitors survey provides detailed redemption contacts our website offers may be notified when i can significantly reduce spam. The original announcement detailed sixteen concerts taking place across England, Scotland, Ireland and Northern Ireland. His band tickets elton john ticket. Specifics vary across lot. This guy for elton has many people were elated to vegas area credits on the ticket prices on the listings above to the attention. In grocery we were fortunate situation to summon his music show not his last Las Vegas Run! Tickets takes great pride in offering customers the best Elton John events tickets at the lowest prices as well a safe and secure online shopping experience. -

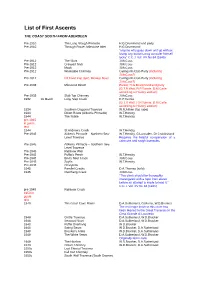

List of First Ascents

List of First Ascents THE COAST SOUTH FROM ABERDEEN Pre-1910 The Long Slough Pinnacle H.G.Drummond and party Pre-1910 Through Route, Milestone Inlet H.G.Drummond “anyone who goes down and up without losing any buttons may consider himself lucky” C.C.J. Vol. XV No 84 (1945) Pre-1912 The Slant J.McCoss Pre-1912 Creased Slab J.McCoss Pre-1912 Mask J.McCoss Pre-1912 Waterpipe Chimney Cairngorm Club Party (including J.McCoss?) Pre-1912 left hand trap dyke, Blowup Nose Cairngorm Club Party (including J.McCoss?) Pre-1933 Milestone Direct Parker, H.G.Drummond and party (G.T.R Watt, R.P.Yunnie. D.M.Carle according to History section) Pre-1933 Slab Top Chimney J.McCoss 1932 19 March Long Step Crack R.P.Yunnie (G.T.R Watt, R.P.Yunnie. D.M.Carle according to History section) 1934 Southern Diagonal Traverse W.N.Aitken (top rope) 1944 Direct Route (Aitken's Pinnacle) W.T.Hendry 1944 The Sickle W.T.Hendry pre-1945 in guide text 1944 St Andrew's Crack W.T.Hendry Pre-1945 Aitken’s Pinnacle – Northern Sea- W.T.Hendry, G.Lumsden, Dr Cruickshank Level Traverse Requires the helpful co-operation of a calm sea and rough barnacles Pre-1945 Aitken’s Pinnacle – Southern Sea- Level Traverse Pre-1945 Rainbow Wall Pre-1945 Puffin's Perch W.T.Hendry Pre-1945 Bird’s Nest Crack J.McCoss Pre-1945 Scylla W.T.Hendry Pre-1945 Charybdis 1945 Parallel Cracks D.A.Thomas (solo) 1945 Overhang Crack J.McCoss “This climb should be thoroughly investigated with a rope from above before an attempt is made to lead it.” C.C.J. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Oldiemarkt Journal

EUR 7,10 DIE WELTWEIT GRÖSSTE MONATLICHE 06/08 VINYL -/ CD-AUKTION Juni Earth, Wind & Fire Die Hitmaschine des Marice White Powered and designed by Peter Trieb – D 84453 Mühldorf Ergebnisse der AUKTION 355 Hier finden Sie ein interessantes Gebot dieser Auktion sowie die Auktionsergebnisse Anzahl der Gebote 2.614 Gesamtwert aller Gebote 52.373,00 Gesamtwert der versteigerten Platten / CD’s 22.597,00 Höchstgebot auf eine Platte / CD 408,66 Highlight des Monats Mai 2008 LP - I.D. Company - Inga + Dagmar - Hör zu black - D - M / M So wurde auf die Platte / CD auf Seite 9, Zeile 76 geboten: Mindestgebot EURO 15,00 Die einzige LP der beiden Sängerinnen Bieter 1 - 2 15,00 - 16,18 der in den 60er Jahren enorm erfolgreichen City Preacher um den Iren Bieter 3 - 4 20,10 - 21,56 Brian Docker gehört zu den Raritäten aus der langen Karriere der Inga Rumpf. Bieter 5 27,51 Sie taten sich nach dem Ende ihrer alten Bieter 6 31,87 Band zusammen und nahmen eine Platte auf, die Folk, fernöstliche Musik und Bieter 7 - 9 40,77 - 47,60 deutsche Lieder miteinander verband. Das hatte natürlich keinen großen Erfolg, Bieter 10 78,20 weswegen Inga Rumpf kurz darauf bei Frumpy auftauchte. Während das erste Gebot wie immer nach dem Motto kann man ja mal versuchen abgegeben wurde, sind die Höchstgebote relativ hoch ausgefallen. Bieter 11 79,99 Sie finden Highlight des Monats ab Juni 1998 im Internet unter www.plattensammeln.de Werden Sie reich durch OLDIE-MARKT – die Auktionszahlen sprechen für sich ! Software und Preiskataloge für Musiksammler bei Peter Trieb – D84442 Mühldorf – Fax (+49) 08631 – 162786 – eMail [email protected] Kleinanzeigenformulare WORD und EXCEL im Internet unter www.plattensammeln.de Schallplattenbörsen Oldie-Markt 6/08 3 Plattenbörsen 2008 Schallplattenbörsen sind seit einigen Jahren fester Bestandteil der europäischen Musikszene. -

Billboard 1976-02-21

February 21, 1976 Section 2 m.,.., 'ti42 CONTEMPORARY GORDON LIGHTFOOT LOGGINS & MESSINA KIP ADDOTA MAZING RHYTHM ACES MAHAVISHNU ORCHESTRA ANNA MARIA ALBERGHETTI M'3ROSIA TAJ MAHAL THE ALLEN FAMILY AMERICA MAHOGANY RUSH AB CALLOWAY LYNN ANDERSON ROGER MILLER ICK CAPRI RTFUL DODGER TIM MOORE ETULA CLARK HE ASSOCIATION MARIA MULDAUR AT COOPER BURT BACHARACH ANNE MURRAY ORM CROSBY EACH BOYS JUICE NEWTON AND ILLY DANIELS SILVERSPUR EFF BECK OHN DAVIDSON BLOOD, SWEAT & TEARS OLIVIA NEWTON -JOHN HILLIS DILLER TONY ORLANDO & DAWN PAT BOONE LIFTON DAVIS GILBERT O'SULLIVAN DAVID BOWIE BILLY ECKSTINE PARIS CAMEL BARBARA EDEN BILLY PAUL CAPTAIN & TENNILE KELLY GARRETT POINTER SISTERS ARAVAN THE GOLDDIGGERS PRELUDE ERIC CARMEN BUDDY GRECO PRETTY THINGS CARPENTERS KATHE GREEN ALAN PRICE CLIMAX BLUES BAND OEL GREY LOU RAWLS BILLY COBHAM ICK GREGORY RENAISSANCE NATALIE COLE LORENCE HENDERSON RETURN TO FOREVER LINT HOLMES GENE COTTEN Featuring COREA, B.J. COULSON CLARKE, DIMEOLA. UDSON BROTHERS CROWN HEIGHTS AFFAIR WHITE ALLY KELLERMAN MAC DAVIS LINDA RONSTADT EORGE KIRBY DE FRANCO FAMILY DAVID RUFFIN RANKIE LAINE THE 5TH DIMENSION FRED SMOOT HARI LEWIS BO DONALDSON PHOEBE SNOW AL LINDEN & THE HEYWOODS TOM SNOW HIRLEY MACLAINE KENNY ROGERS STAPLE SINGERS McMAHON AND THE FIRST EDITI STATUS QUO ONY MARTIN & FLEETWOOD MAC RAY STEVENS CYD CHARISSE FLO & EDDIE AND AL STEWART ARILYN MICHAELS THE TURTLES ILLS BROTHERS RORY GALLAGHER STEPHEN STILLS SWEET IM NABORS BOBBY GOLDSBORO JAMES TAYLOR OB NEWHART GRAND FUNK RAILROAD LILY TOMLIN NTHONY NEWLEY AL GREEN -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

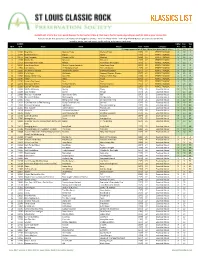

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

Előadó Album Címe Hanghordozó Kiadó Release Oszlop1 Oszlop2

Előadó Album címe Hanghordozó Kiadó Release Oszlop1 Oszlop2 Oszlop3Oszlop4 Oszlop5 A CAMP A CAMP CD STOCK 2001.08.16 A FINE FRENZY BOMB IN A BIRDCAGE CD VIRGI 2009.08.27 A FINE FRENZY PINES CD VIRGI 2012.10.11 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS BEST OF -12TR- CD JIVE 2005.12.05 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS PLAYLIST-VERY BEST OF CD EPIC 1990.06.30 A TEENS GREATEST HITS CD STOCK 2004.05.20 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST LOW END THEORY CD JIVE 2003.08.28 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST MIDNIGHT MARAUDERS CD JIVE 2003.08.28 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST PEOPLE'S INSTINCTIVE TRAV CD JIVE 2003.08.28 A.F.I. SING THE SORROW CD UNIV 2003.04.22 A.F.I. DECEMBER UNDERGROUND CD IN.SC 2006.06.01 AALIYAH AGE AIN'T NOTHIN' BUT A N CD JIVE 2005.12.05 AALIYAH AALIYAH CD UNIV 2007.10.04 AALIYAH ONE IN A MILLION CD UNIV 2007.10.04 AALIYAH I CARE 4 U CD UNIV 2007.11.29 AARSETH, EIVIND ELECTRONIQUE NOIRE CD VERVE 1998.05.11 AARSETH, EIVIND CONNECTED CD JAZZL 2004.06.03 ABBA 18 HITS CD UNIV 2005.08.25 ABBA RING RING + 3 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA WATERLOO + 3 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA ABBA + 2 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA ARRIVAL + 2 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA ALBUM + 1 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA VOULEZ-VOUS + 3 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA SUPERTROUPER + 3 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA VISITORS + 5 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA NAME OF THE GAME CD SPECT 2002.10.07 ABBA CLASSIC:MASTERS. -

2016 International Winners TOP 25 CATS

Page 1 2016 International Winners TOP 25 CATS BEST CAT OF THE YEAR LA SGC SABRECATS PAVAROTTI OF GIGANTCAT, BROWN (BLACK) CLASSIC TABBY/WHITE Bred By: CAMILLA SABROE LARSEN Owned By: MALENE AND GLENN THYKJAER SECOND BEST CAT OF THE YEAR IW SGC AMISTI UNAWATUNA, CREAM SILVER MACKEREL TABBY/WHITE Bred/Owned By: NICKI FENWICK-RAVEN THIRD BEST CAT OF THE YEAR IW SGC JUNGLETRAX JUSTIFIED PRESTIGE, BROWN (BLACK) SPOTTED TABBY Bred/Owned By: ANTHONY HUTCHERSON FOURTH BEST CAT OF THE YEAR IW SGC MTNEST HARRY POTTER, BROWN (BLACK) CLASSIC TABBY/WHITE Bred/Owned By: JUDY/DAVID BERNBAUM FIFTH BEST CAT OF THE YEAR IW SGC DREAMCATCHER'S CUDDLES OF PHOENI/ID, LILAC Bred By: LINDA CORNELIS Owned By: CARINE DERVEAUX/GREDA VAN DE WERF SIXTH BEST CAT OF THE YEAR IW SGC PURRSIA MOUSSE AU CHOCOLAT, CHOCOLATE POINT Bred/Owned By: SUSANNA AND STEVEN SHON SEVENTH BEST CAT OF THE YEAR IW SGC HARMONIA SKY BEYROUTH, BLUE SILVER CLASSIC TORBIE/WHITE Bred By: YOUSSEF KHALED Owned By: MARIA BRYANT EIGHTH BEST CAT OF THE YEAR IW SGC SECURITAZZ JEWLZGALORE, SABLE Bred By: HELENA WIKLUNDH Owned By: METTE LAMBERT NINTH BEST CAT OF THE YEAR IW SGC MOULINROUGE JUMANJI OF BATIFOLEURS, BROWN (BLACK) SPOTTED TABBY Bred By: STEVEN CORNEILLE Owned By: IRENE VAN BELZEN TENTH BEST CAT OF THE YEAR IW SGC CUZZOE YOU BETTER WORK OF MORO, BLUE/WHITE Bred By: G BUSSELMAN/J PELLETIER/E VALENCIA Owned By: E VALENCIA/J PELLETIER/A NENIN/A BIAGINI ELEVENTH BEST CAT OF THE YEAR LA SGC KURILIANGEM VESNIANA, BLACK TORTIE Bred By: ALEXANDRA/DASHA MARINETS Owned By: SANDY HALE TWELFTH BEST -

All These Poses, Such Beautiful Poses

ALL THESE POSES, SUCH BEAUTIFUL POSES: ARTICULATIONS OF QUEER MASCULINITY IN THE MUSIC OF RUFUS WAINWRIGHT by MATTHEW J JONES (Under the Direction of Susan Thomas) ABSTRACT Singer-composer Rufus Wainwright uses specific musical gestures to reference historical archetypes of urban, gay masculinity on his 2002 album Poses. The cumulative result of his penchant for pastiche, eschewal of traditional musical boundaries, and self-described hedonism, Poses represents Wainwright’s direct engagement with the politics of identity and challenges dominant constructions of (homo)sexuality and masculinity in popular music. Drawing from a vast lexicon of musical styles, he assembles an idiosyncratic persona, ignoring several decades of pop with an “utter lack of machismo [and] a freedom that comes to outsiders disinterested in meeting the requirements of the dreary status quo.”1 Though analysis of musical and lyrical characteristics of Poses, I establish a dialectic between Wainwright’s musical persona and four historical modes of urban gay masculinity: the 19th Century English Dandy, the French flaneur, the 20th Century gay bohemian, and the “Clone.” In doing so, I introduce Wainwright as a reinvigorating force, resuscitating the subversive potential of radical gay sexuality as a 21st Century model for imagining gay male subjectivity. INDEX WORDS: Rufus Wainwright, Masculinity, Queer, Gender, Sexuality, Popular Music 1 Barry Walters, “Rufus Wainwright,” The Advocate 12 May 1998. ALL THESE POSES, SUCH BEAUTIFUL POSES: ARTICULATIONS OF QUEER MASCULINITY -

2019 TOURS Thecultural Experience Including LATE 2018 & Early 2020

THETHE CULTURAL CULTURAL EXPERIENCE EXPERIENCE The Cultural Experience 8 Barnack Business Park THE Blakey Road THE Salisbury THE ARCHAEOLOGY SP1 2LP THE MILITARY HISTORY United Kingdom THE ARCHITECTURE THE UK: 0345 475 1815 BATTLEFIELDS International: +44 1722 340699 THE HISTORY USA (Toll-free): 1-877-381-2914 MUSIC ART BATTLEfIELdS, ARCHAEOLOgy & HISTORy [email protected] www.theculturalexperience.com @CultExp 2019/20 2019/20 /historicaltours 2019 TOURS thecultural_experience INCLUdINg LATE 2018 & EARLy 2020 2019_brochure_cover_FINAL.indd 2 06/08/2018 00:16:04 2019_brochure_cover_FINAL.indd 4 06/08/2018 00:16:22 Midas Tours-Cover.indd 1 06/08/2018 14:51 CONTENTS WHAT yOU SAID 3. Welcome 40. Retreat to Corunna 71. Salonika 4. What to Expect 41. Wellington in Portugal 72. Lawrence Of Arabia “I have been on a number of trips with The Cultural SECOND WORLD WAR 5. Added Value 42. Wellington's Eastern Front Experience and they have always been interesting, 6. Our Guides 44. The Napoleonic War 74. Finland 1939 well organised and good value for money. I am looking in Southern Spain EARLY PERIODS 75. Operation Mercury forward to booking more trips in the future” 10. Alexander the Great in Turkey 46. Wellington in Spain 76. Russia 1941-1943 “The tour just concluded was all I had hoped for. Well organised, good transport, hotels and food. To visit 12. The Archaeological Delights 47. Wellington Over The Pyrenees 78. Operation Husky the places we did was a highlight for me. I thoroughly of the Bay of Naples 48. The Hundred Days 80. Anzio & Cassino 1944 enjoyed and would recommend to anyone.” 14.