Aylsham Local History Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norfolk Through a Lens

NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service 2 NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service History and Background The systematic collecting of photographs of Norfolk really began in 1913 when the Norfolk Photographic Survey was formed, although there are many images in the collection which date from shortly after the invention of photography (during the 1840s) and a great deal which are late Victorian. In less than one year over a thousand photographs were deposited in Norwich Library and by the mid- 1990s the collection had expanded to 30,000 prints and a similar number of negatives. The devastating Norwich library fire of 1994 destroyed around 15,000 Norwich prints, some of which were early images. Fortunately, many of the most important images were copied before the fire and those copies have since been purchased and returned to the library holdings. In 1999 a very successful public appeal was launched to replace parts of the lost archive and expand the collection. Today the collection (which was based upon the survey) contains a huge variety of material from amateur and informal work to commercial pictures. This includes newspaper reportage, portraiture, building and landscape surveys, tourism and advertising. There is work by the pioneers of photography in the region; there are collections by talented and dedicated amateurs as well as professional art photographers and early female practitioners such as Olive Edis, Viola Grimes and Edith Flowerdew. More recent images of Norfolk life are now beginning to filter in, such as a village survey of Ashwellthorpe by Richard Tilbrook from 1977, groups of Norwich punks and Norfolk fairs from the 1980s by Paul Harley and re-development images post 1990s. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

The Settlement of East and West Flegg in Norfolk from the 5Th to 11Th Centuries

TITLE OF THESIS The settlement of East and West Flegg in Norfolk from the 5th to 11th centuries By [Simon Wilson] Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted For the Degree of Masters of Philosophy Year 2018 ABSTRACT The thesis explores the –by and English place names on Flegg and considers four key themes. The first examines the potential ethnicity of the –bys and concludes the names carried a distinct Norse linguistic origin. Moreover, it is acknowledged that they emerged within an environment where a significant Scandinavian population was present. It is also proposed that the cluster of –by names, which incorporated personal name specifics, most likely emerged following a planned colonisation of the area, which resulted in the takeover of existing English settlements. The second theme explores the origins of the –by and English settlements and concludes that they derived from the operations of a Middle Saxon productive site of Caister. The complex tenurial patterns found between the various settlements suggest that the area was a self sufficient economic entity. Moreover, it is argued that royal and ecclesiastical centres most likely played a limited role in the establishment of these settlements. The third element of the thesis considers the archaeological evidence at the –by and English settlements and concludes that a degree of cultural assimilation occurred. However, the presence of specific Scandinavian metal work finds suggests that a distinct Scandinavian culture may have survived on Flegg. The final theme considers the economic information recorded within the folios of Little Domesday Book. It is argued that both the –by and English communities enjoyed equal economic status on the island and operated a diverse economy. -

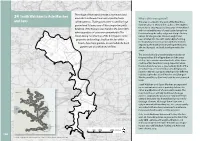

24 South Walsham to Acle Marshes and Fens

South Walsham to Acle Marshes The village of Acle stands beside a vast marshland 24 area which in Roman times was a great estuary Why is this area special? and Fens called Gariensis. Trading ports were located on high This area is located to the west of the River Bure ground and Acle was one of those important ports. from Moulton St Mary in the south to Fleet Dyke in Evidence of the Romans was found in the late 1980's the north. It encompasses a large area of marshland with considerable areas of peat located away from when quantities of coins were unearthed in The the river along the valley edge and along tributary Street during construction of the A47 bypass. Some valleys. At a larger scale, this area might have properties in the village, built on the line of the been divided into two with Upton Dyke forming beach, have front gardens of sand while the back the boundary between an area with few modern impacts to the north and a more fragmented area gardens are on a thick bed of flints. affected by roads and built development to the south. The area is basically a transitional zone between the peat valley of the Upper Bure and the areas of silty clay estuarine marshland soils of the lower reaches of the Bure these being deposited when the marshland area was a great estuary. Both of the areas have nature conservation area designations based on the two soil types which provide different habitats. Upton Broad and Marshes and Damgate Marshes and Decoy Carr have both been designated SSSIs. -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Regulation 25 Consultation

Regulation 25 Consultation Technical & Public Consultation Summary August 2009 Greater Norwich Development Partnership Regulation 25 Consultation 233902 BNI NOR 1 A PIMS 233902BN01/Report 14 August 2009 Technical & Public Consultation Summary August 2009 Greater Norwich Development Partnership Regulation 25 Consultation Issue and revision record Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description A 03.08.09 Needee Myers Draft Report B 15.08.09 Needee Myers Emma Taylor Eddie Tyrer Final Report This document has been prepared for the titled project or Mott MacDonald accepts no responsibility or liability for this named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used document to any party other than the person by whom it was for any other project without an independent check being commissioned. carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Mott MacDonald being obtained. Mott MacDonald accepts no To the extent that this report is based on information supplied responsibility or liability for the consequence of this document by other parties, Mott MacDonald accepts no liability for any being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it loss or damage suffered by the client, whether contractual or was commissioned. Any person using or relying on the tortious, stemming from any conclusions based on data document for such other purpose agrees, and will by such supplied by parties other than Mott MacDonald and used by use or reliance be taken to confirm his agreement to indemnify Mott MacDonald in preparing this report. Mott MacDonald for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Regulation 25 Consultation Content Chapter Title Page 1. -

Transactions 1948

PRESENTED 2 1 MAR 1952 TRANSACTIONS OF THE JtiiU'folli anil ilu fluid) NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY For the Year 1948 VOL. XVI Part v. Edited by Major A. Buxton NORWICH Printed by The Soman-Wherry Press Ltd., Norwich. February, 1949 Price 10 /- PAST PRESIDENTS REV. JOSEPH CROMPTON, M.A. ... 1869—70 ... ... ... 1870—71 "! HENRY STEVENSON, KL.S. !!! 1871—72 MICHAEL BEVERLEY, M.D ... 1872—73 FREDERIC KITTON, Hon. F.R.M.S. ... ... 1873—74 H. D. GELDART 1874—75 JOHN B. BRIDGMAN 1875—76 T. G. BAYFIELD ... 1876—77 F. W. HARMER, F.G.S. ... ... ... 1877—78 ... 1878—79 THOMAS SOUTHWELL, F.Z.S. 1879—80 OCTAVIUS CORDER ... 1880—81 ... 1881—82 J. H. GURNEY, Jun., F.Z.S H. D. GELDART 1882—83 H. M. UPCHER, F.Z.S 1883—84 FRANCIS SUTTON, F.C.S ... 1884—85 MAJOR H. W. FIELDEN, C.B., F.G.S., C.M z.s. ... 1885—86 SIR PETER EADE, M.D., F.R.C.P. ... 1886—87 SIR EDWARD NEWTON, K.C.M.G., F.L.S. C.M.Z.S. ... 1887—88 1888—89 J. H. GURNEY, F.L.S., F.Z.S SHEPHARD T. TAYLOR, M.B. 1889—90 HENRY SEEBOHM, F.L.S., F.Z.S. ... ... 1890—91 F. D. WHEELER, M.A., LL.D 1891—92 HORACE B. WOODWARD, F.G.S. ... ... 1892—93 THOMAS SOUTHWELL, F.Z.S. 1893—94 C. B. PLOWRIGHT, M.D ... 1894—95 H. D. GELDART ... 1895—96 SIR F. C. M. BOILEAU, Bart., F.Z.S., F.S !.. 1896—97 E. W. PRESTON, F.R.Met.Soc. -

The Norfolk & Norwich

BRITISH MUSEUM (NATURAL HISTORY) TRANSACTIONS 2 7 JUN 1984 exchanged OF GENfcriAL LIBRARY THE NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY Edited by: P. W. Lambley Vol. 26 Part 5 MAY 1984 TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK AND NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY Volume 26 Part 5 (May 1984) Editor P. W. Lambley ISSN 0375 7226 U: ' A M «SEUV OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY 1984-85 j> URAL isSTORY) 2? JUH1984 President: Dr. R. E. Baker Vice-Presidents: P. R. Banham, A. Bull, K. B. Clarke, E. T. Daniels, K. C. Durrant, E. A. Ellis, R. Jones, M. J. Seago, J. A. Steers, E. L. Swann, F. J. Taylor-Page Chairman: Dr. G. D. Watts, Barn Meadow, Frost’s Lane, Gt. Moulton. Secretary: Dr. R. E. Baker, 25 Southern Reach, Mulbarton, NR 14 8BU. Tel. Mulbarton 70609 Assistant Secretary: R. N. Flowers, Heatherlands, The Street, Brundall. Treasurer: D. A. Dorling, St. Edmundsbury, 6 New Road, Heathersett. Tel. Norwich 810318 Assistant Treasurer: M. Wolner Membership Committee: R. Hancy, Tel. Norwich 860042 Miss J. Wakefield, Post Office Lane, Saxthorpe, NR1 1 7BL. Programme Committee: A. Bull, Tel. Norwich 880278 Mrs. J. Robinson, Tel. Mulbarton 70576 Publications Committee: R. Jones. P. W. Lambley & M. J. Seago (Editors) Research Committee: Dr. A. Davy, School of Biology, U.E.A., Mrs. A. Brewster Hon. Auditor. J. E. Timbers, The Nook, Barford Council: Retiring 1985; D. Fagg, J. Goldsmith, Miss F. Musters, R. Smith. Retiring 1986 Miss R. Carpenter, C. Dack, Mrs. J. Geeson, R. Robinson. Retiring 1987 N. S. Carmichael, R. Evans, Mrs.L. Evans, C. Neale Co-opted members: Dr. -

Cabinet 07 October 2019

Cabinet Date: Monday 7 October 2019 Time: 10am Venue: Edwards Room, County Hall, Norwich Persons attending the meeting are requested to turn off mobile phones. Membership: Cllr Andrew Proctor Chairman. Leader and Cabinet Member for Strategy & Governance. Cllr Graham Plant Vice-Chairman. Deputy Leader and Cabinet Member for Growing the Economy. Cllr Bill Borrett Cabinet Member for Adult Social Care, Public Health & Prevention Cllr Margaret Dewsbury Cabinet Member for Communities & Partnerships Cllr John Fisher Cabinet Member for Children’s Services Cllr Tom FitzPatrick Cabinet Member for Innovation, Transformation & Performance Cllr Andy Grant Cabinet Member for Environment & Waste Cllr Andrew Jamieson Cabinet Member for Finance Cllr Greg Peck Cabinet Member for Commercial Services & Asset Management Cllr Martin Wilby Cabinet Member for Highways, Infrastructure & Transport WEBCASTING This meeting will be filmed and streamed live via YouTube on the NCC Democrat Services channel. The whole of the meeting will be filmed, except where there are confidential or exempt items and the footage will be available to view via the Norfolk County Council CMIS website. A copy of it will also be retained in accordance with the Council’s data retention policy. Members of the public may also film or record this meeting. If you do not wish to have your image captured, you should sit in the public gallery area. If you have any queries regarding webcasting of meetings, please contact the committee Team on 01603 228913 or email [email protected] 1 Cabinet 7 October 2019 A g e n d a 1 To receive any apologies. 2 Minutes Page 5 To confirm the minutes from the Cabinet Meeting held on Monday 2 September 2019. -

North Norfolk Landscape Character Assessment Contents

LCA cover 09:Layout 1 14/7/09 15:31 Page 1 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT NORTH NORFOLK Local Development Framework Landscape Character Assessment Supplementary Planning Document www.northnorfolk.org June 2009 North Norfolk District Council Planning Policy Team Telephone: 01263 516318 E-Mail: [email protected] Write to: Planning Policy Manager, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, NR27 9EN www.northnorfolk.org/ldf All of the LDF Documents can be made available in Braille, audio, large print or in other languages. Please contact 01263 516318 to discuss your requirements. Cover Photo: Skelding Hill, Sheringham. Image courtesy of Alan Howard Professional Photography © North Norfolk Landscape Character Assessment Contents 1 Landscape Character Assessment 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 What is Landscape Character Assessment? 5 2 North Norfolk Landscape Character Assessment 9 2.1 Methodology 9 2.2 Outputs from the Characterisation Stage 12 2.3 Outputs from the Making Judgements Stage 14 3 How to use the Landscape Character Assessment 19 3.1 User Guide 19 3.2 Landscape Character Assessment Map 21 Landscape Character Types 4 Rolling Open Farmland 23 4.1 Egmere, Barsham, Tatterford Area (ROF1) 33 4.2 Wells-next-the-Sea Area (ROF2) 34 4.3 Fakenham Area (ROF3) 35 4.4 Raynham Area (ROF4) 36 4.5 Sculthorpe Airfield Area (ROF5) 36 5 Tributary Farmland 39 5.1 Morston and Hindringham (TF1) 49 5.2 Snoring, Stibbard and Hindolveston (TF2) 50 5.3 Hempstead, Bodham, Aylmerton and Wickmere Area (TF3) 51 5.4 Roughton, Southrepps, Trunch -

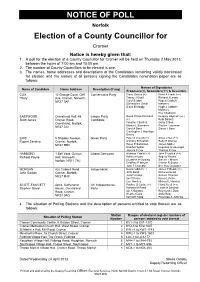

Notice of Poll

NOTICE OF POLL Norfolk Election of a County Councillor for Cromer Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Cromer will be held on Thursday 2 May 2013, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors COX 12 Grange Court, Cliff Conservative Party Claire Davies (+) Peter A Frank (++) Hilary Ave, Cromer, Norwich, Tracey J Khalil Richard J Leeds NR27 0AF Carol Selwyn Rupert Cabbell- Gwendoline Smith Manners Diana B Meggy Hugh J Cabbell- Manners Roy Chadwick EASTWOOD Overstrand Hall, 48 Labour Party David Phillip-Pritchard Gregory Hayman (++) Scott James Cromer Road, Candidate (+) Ruth Bartlett Overstrand, Norfolk, Timothy J Bartlett Garry S Bone NR27 0JJ Marion L Saunders Pauline Tuynman Carol A Bone Simon J Bone Christopher J Hamilton- Emery ERIS 5 Shipden Avenue, Green Party Peter A Crouch (+) Alicia J Hull (++) Rupert Sandino Cromer, Norfolk, Anthony R Bushell Ruby B Warner NR27 9BD Helen E Swanston James Spiller Heather Spiller Huguette A Gazengel Jessica F Cox Thomas P Cox HARBORD 1 Bell Yard, Gunton Liberal Democrat Andreas Yiasimi (+) John Frosdick (++) Richard Payne Hall, Hanworth, Kathleen Lane Angela Yiasimi Norfolk, NR11 7HJ Elizabeth A Golding -

Autumn 2009 NUMBER EIGHTEEN Norfolk Historic Buildings Group Non-Members: £1.00

HBG ewsletter NAutumn 2009 NUMBER EIGHTEEN Norfolk Historic Buildings Group Non-Members: £1.00 www.nhbg.org.uk NHBG preparing to invade Barningham Hall approaching by the west facade. The early seventeenth century house has unusual double dormers. The oriel window protruding from the south face was an introduction by the Reptons in the early nineteenth century. Contents Chair ..................................................................................................................2 Vernacular Architecture Group .............................................14 Tacolneston Project: NHBG Journal No 4 ........................................2 Tacolneston Project ....................................................................15 Pastures New: Tydd St Giles and Wisbech .....................................3 Norfolk Rural Schools Survey.................................................16 Fifteenth-century piety in the Glaven valley .................................4 New NHBG Website. www.NHBG.org.uk ........................16 Possible Columbarium at St Nicholas, Blakeney...........................5 A Digest of Buildings Visited Since March 2009 ............17 The Beccles Day Saturday ......................................................................6 Annual General Meeting ...........................................................17 Leman House, Beccles ..............................................................................7 Gressenhall History Day May2009.......................................18 Castle Acre: Castle and