AB29 1-4 Fertig.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GREECE in Gures

GREECE in gures July - September 2015 ΤΑΤΙΣ Σ Τ Ι Η Κ Κ Η Ι Ν Α Ρ Η Χ Λ Η Λ Ε • www.statistics.gr HELLENIC STATISTICAL AUTHORITY 1 Foreword FOREWORD The Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) through the new quarterly publication Greece in figures, published in both the Greek and English languages, presents statistical data providing an updated demographic, social and economic picture of Greece in a clear and comprehensive manner. The publication Greece in figures is intended for users of sta - tistics who seek to have a comprehensive view of Greece, on the basis of the most recent statistical data. The statistical time series included in this publication are, mostly, compiled by ELSTAT. Furthermore, for comparability reasons, the pub - lication also presents, by theme, selected tables with statisti - cal data of EU Member States. The publication will be updated with the most recent data on a quarterly basis and will be posted on the portal of ELSTAT on the first Wednesday of January, April, July and Octo - ber . For more information on the data and statistics provided in Greece in figures , please contact the Division of Statistical In - formation and Publications of ELSTAT (tel: +30 213 1352021, +30 213 1352301, e-mail: [email protected]). We welcome any suggestions and recommendations on the content of the publication. Andreas V. Georgiou President of ELSTAT 2 3 Contents CONTENTS Foreword 3 Land and climate 1. Surface area of Greece 11 2. Principal mountains of Greece 11 3. Principal lakes of Greece 11 4. Principal rivers of Greece 12 5. -

Land Routes in Aetolia (Greece)

Yvette Bommeljé The long and winding road: land routes in Aetolia Peter Doorn (Greece) since Byzantine times In one or two years from now, the last village of the was born, is the northern part of the research area of the southern Pindos mountains will be accessible by road. Aetolian Studies Project. In 1960 Bakogiánnis had Until some decades ago, most settlements in this backward described how his native village of Khelidón was only region were only connected by footpaths and mule tracks. connected to the outside world by what are called karélia In the literature it is generally assumed that the mountain (Bakogiánnis 1960: 71). A karéli consists of a cable population of Central Greece lived in isolation. In fact, a spanning a river from which hangs a case or a rack with a dense network of tracks and paths connected all settlements pulley. The traveller either pulls himself and his goods with each other, and a number of main routes linked the to the other side or is pulled by a helper. When we area with the outside world. visited the village in 1988, it could still only be reached The main arteries were well constructed: they were on foot. The nearest road was an hour’s walk away. paved with cobbles and buttressed by sustaining walls. Although the village was without electricity, a shuttle At many river crossings elegant stone bridges witness the service by donkey supplied the local kafeneíon with beer importance of the routes. Traditional country inns indicate and cola. the places where the traveller could rest and feed himself Since then, the bulldozer has moved on and connected and his animals. -

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: a Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: A Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944 ARGYRIOS MAMARELIS Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy The European Institute London School of Economics and Political Science 2003 i UMI Number: U613346 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613346 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 9995 / 0/ -hoZ2 d X Abstract This thesis addresses a neglected dimension of Greece under German and Italian occupation and on the eve of civil war. Its contribution to the historiography of the period stems from the fact that it constitutes the first academic study of the third largest resistance organisation in Greece, the 5/42 regiment of evzones. The study of this national resistance organisation can thus extend our knowledge of the Greek resistance effort, the political relations between the main resistance groups, the conditions that led to the civil war and the domestic relevance of British policies. -

A Checklist of Greek Reptiles. II. the Snakes 3-36 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft Für Herpetologie E.V., Wien, Austria, Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 1989 Band/Volume: 2_1_2 Autor(en)/Author(s): Chondropoulos Basil P. Artikel/Article: A checklist of Greek reptiles. II. The snakes 3-36 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at HERPETOZOA 2 (1/2): 3-36 Wien, 30. November 1989 A checklist of Greek reptiles. II. The snakes Liste der Reptilien Griechenlands. II. Schlangen BASIL P. CHONDROPOULOS ABSTRACT: The systematic status and the geographical distribution of the 30 snake taxa occurring in Greece are presented. Compared to lizards, the Greek snakes show a rather reduced tendency to form subspecies; from the total of 21 species listed, only 5 are represented by more than one subspecies. No endemic species has been recorded, though at the subspecific level 8 endemisms are known in the Aegean area. Many new locality records are provided. KURZFASSUNG: Der systematische Status und die geographische Verbreitung der 30 in Griechenland vorkommenden Schlangentaxa wird behandelt. Verglichen mit den Eidechsen zeigen die Schlangen in Griechenland eher eine geringe Tendenz zur Ausbildung von Unterarten; von ins- gesamt 21 aufgeführten Arten sind nur 5 durch mehr als eine Unterart repräsentiert. Keine endemi- sche Art wurde bisher beschrieben, obwohl auf subspezifischem Niveau 8 Endemismen im Raum der Ägäis bekannt sind. Zahlreiche neue Fundorte werden angegeben. KEYWORDS: Ophidia, Checklist, Greece INTRODUCTION The Greek snake fauna consists of 21 species belonging to 4 families: Typh- lopidae (1 species), Boidae (1 species), Colubridae (14 species) and Viperidae (5 species). Sixteen species are either monotypic or each one is represented in Greece by only one subspecies while the remaining rest is divided into a sum of 14 subspecies. -

Cryptoperla Dui, Sp

Kovács, T., G. Vinçon, D. Murányi, & I. Sivec. 2012. A new Perlodes species and its subspecies from the Balkan Peninsula (Plecoptera: Perlodidae). Illiesia, 8(20):182-192. Available online: http://www2.pms-lj.si/illiesia/Illiesia08-20.pdf urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:71EF3B40-E042-4D86-987E-6E7B609AE5B1 A NEW PERLODES SPECIES AND ITS SUBSPECIES FROM THE BALKAN PENINSULA (PLECOPTERA: PERLODIDAE) Tibor Kovács1, Gilles Vinçon2, Dávid Murányi3, & Ignac Sivec4 1 Mátra Museum, Kossuth Lajos u. 40, H-3200 Gyöngyös, Hungary E-mail: [email protected] 2 55 Bd Joseph Vallier, F 38100 Grenoble, France E-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum, H-1088 Baross u. 13, Budapest, Hungary E-mail : [email protected] 4 Slovenian Museum of Natural History, Prešernova 20, P.O. Box 290, SLO-1001 Ljubljana, Slovenia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Perlodes floridus sp. n. is described on the basis of female, male, egg and larva from the Balkan Peninsula (Montenegro, Albania, Greece). Due to differences in egg structure and male paraprocts, populations from the Greek Peloponnes are described as Perlodes floridus peloponnesiacus ssp. n. Notes on some additional species of the genus are also given. Keywords: Plecoptera, Perlodidae, taxonomy, Perlodes, new species, new subspecies INTRODUCTION Montenegro, Albania and the western Greek During 2009 and 2010, the first author carried out mainland (Fig. 25). investigations on the aquatic insect fauna in the The genus Perlodes has a disjunct Palaeartic Cijevna River of Montenegro, recommended as a distribution area. There are five species in the West notable habitat by Vladimir Pešić and Miladin Jakić. -

Aquatic Dance Flies (Diptera, Empididae, Clinocerinae and Hemerodromiinae) of Greece: Species Richness, Distribution and Description of Five New Species

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 724: Aquatic53–100 (2017) dance flies( Diptera, Empididae, Clinocerinae and Hemerodromiinae)... 53 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.724.21415 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Aquatic dance flies (Diptera, Empididae, Clinocerinae and Hemerodromiinae) of Greece: species richness, distribution and description of five new species Marija Ivković1, Josipa Ćevid2, Bogdan Horvat†, Bradley J. Sinclair3 1 Division of Zoology, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Rooseveltov trg 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 2 Zagrebačka 21, 22320 Drniš, Croatia 3 Canadian National Collection of Insects & Cana- dian Food Inspection Agency, Ottawa Plant Laboratory – Entomology, Ottawa, Canada † Deceased, formerly with Slovenian Museum of Natural History Corresponding author: Bradley J. Sinclair ([email protected]) Academic editor: D. Whitmore | Received 3 October 2017 | Accepted 6 December 2017 | Published 21 December 2017 http://zoobank.org/BCDF3F20-7E27-4CCF-A474-67DA61308A78 Citation: Ivković M, Ćevid J, Horvat B, Sinclair BJ (2017) Aquatic dance flies (Diptera, Empididae, Clinocerinae and Hemerodromiinae) of Greece: species richness, distribution and description of five new species. ZooKeys 724: 53–100. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.724.21415 Abstract All records of aquatic dance flies (37 species in subfamily Clinocerinae and 10 species in subfamily Hemerodromiinae) from the territory of Greece are summarized, including previously unpublished data and data on five newly described species Chelifera( horvati Ivković & Sinclair, sp. n., Wiedemannia iphigeniae Ivković & Sinclair, sp. n., W. ljerkae Ivković & Sinclair, sp. n., W. nebulosa Ivković & Sinclair, sp. n. and W. pseudoberthelemyi Ivković & Sinclair, sp. n.). The new species are described and illustrated, the male terminalia of Clinocera megalatlantica (Vaillant) are illustrated and the distributions of all species within Greece are listed. -

Settlement Analysis of the Mornos Earth Dam (Greece): Evidence from Numerical Modeling and Geodetic Monitoring

Engineering Structures 30 (2008) 3074–3081 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Engineering Structures journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/engstruct Settlement analysis of the Mornos earth dam (Greece): Evidence from numerical modeling and geodetic monitoring Vassilis Gikas a,∗, Michael Sakellariou b a Laboratory of General Geodesy, School of Rural and Surveying Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, GR 15780, Greece b Laboratory of Structural Mechanics and Technical Works, School of Rural and Surveying Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, GR 15780, Greece article info a b s t r a c t Article history: This paper studies the long-term (>30 years) settlement behavior of the Mornos dam on the basis of Received 28 December 2007 finite element analysis and vertical displacement data. It compares actually measured deformations Received in revised form resulting from a continuous geodetic monitoring record of the dam behavior with a numerical back 28 March 2008 analysis. Our aim is to explain the actual deformation history on the basis of the mechanical behavior Accepted 31 March 2008 of the dam. The deformation monitoring record consists of precise leveling data of a large number of Available online 27 May 2008 control stations established along the crest and the inspection gallery of the dam, as well as settlements derived by magnetic extensometers placed inside the dam body. Overall, the available data cover the Keywords: Dam settlement phases of construction, first filling of the reservoir and most of the operational time of the dam. The Finite element analysis numerical modeling assumes 2D plane-strain conditions to obtain the displacement and the stress–strain Precise leveling characteristics of the abutments and the dam at eleven equally-spaced cross sections. -

Ljubljana. December 2009

LJUBLJANA. DECEMBER 2009 FIRST RECORD OF NEVRORTHIDAE FROM SLOVENIA Joshua R. JONESl and Dusan DEVETAK2 ITexas A&M University, College Station, TX, 77843-2475, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biology, FNM, University of Maribor, Koroska c. 160, 2000 Maribor, Slovenia Abstract - Nevrorthus apatelios H. Aspock, U. Aspock et Holzel, 1977 is recorded for the first time from Slovenia. The finding on the southwest slopes of the eastern Julian Alps represents the northernmost record for the family in Europe. A list of known localities for N. apatelios is provided in an appendix. KEY WORDS: Neuroptera, Nevrorthus apatelios, new record, Slovenia Izvlecek - PRVA NAJDBA DRUZINE NEVRORTHIDAE V SLOVENIJI Prvic je v Sloveniji zabelezena najdba vrste Nevrorthus apatelios H. Aspock, U. Aspock et Holzel, 1977. Najdba najugozahodnih pobocjih vzhodnih Julijskih Alp je najsevernejsa najdba druzine v Evropi. Spisek znanih najdisc vrste N. apatelios je sestavljen v dodatku. KLJUCNE BESEDE: Neuroptera, Nevrorthus apatelios, nova najdba, Slovenija Recently, Letardi et ale (2005) reported the occurrence of Nevrorthus apatelios H. Aspock, U. Aspock et Holzel (1977) in the Friuli region of northern Italy_ This dis covery significantly expanded the known geographic distribution of this primarily Balkan species, increasing its documented range by 3° latituqe to the north and 4° longitude to the west. This unexpected discovery has suggested that nevrorthids, which are rarely collected and appear to be very locally distributed, may have a greater distribution in southeastern Europe than previously realized. On 22 June 2008, the first author collected two adult male specimens of N. apate lios in the Goriska region of western Slovenia. -

Entipo-Toutist.Pdf

Εύηνος… «Το ποτάμι λεωφόρος των βουνών» Evinos… the river “avenue” of the mountains Φαράγγι Βουραϊκού… Mαγεμένοι από το τοπίο, συνεπαρμένοι από την ιστορία. Vouraikos Gorge …enchanted by the landscape, overwhelmed by the history Αλφειός... O ερωτευμένος ποταμός! Alfios…the river in love! Αχελώος… Το Κέρας της Αμάλθειας είναι ο ίδιος ο ποταμός, που θα σας μαγέψει .... Acheloos…the river is the Horn of Plenty itself, it will enchant you…. Εύηνος… «Το ποτάμι λεωφόρος των βουνών» Evinos… the river “avenue” of the mountains Φαράγγι Βουραϊκού… Mαγεμένοι από το τοπίο, συνεπαρμένοι από την ιστορία. Vouraikos Gorge …enchanted by the landscape, overwhelmed by the history Αλφειός... O ερωτευμένος ποταμός! Alfios…the river in love! Αχελώος… Το Κέρας της Αμάλθειας είναι ο ίδιος ο ποταμός, που θα σας μαγέψει .... Acheloos…the river is the Horn of Plenty itself, it will enchant you…. EvinosΕύηνος Στο ρου του Ευήνου The flow of Evinos Ο Εύηνος είναι το ποτάμι της Ναυπακτίας που διατρέχει διαγώνια τη γη Evinos is the river of Nafpaktia, which crosses its land diagonally, with της με κατεύθυνση από τα ΒΑ προς τα ΝΔ. Οι πηγές του εντοπίζονται στα a direction from NE to SW. Its spring is found on Vardousia, Sarantena όρη Βαρδούσια, Σαράνταινα και Κοκκινιάς και διανύει 113 χλμ. ως την and Kokkinia Mts and it runs 113 kilometers before flowing into Patraikos εκβολή του στον Πατραϊκό κόλπο. Ο Εύηνος συνδέεται με πολλούς αρχαι- Gulf. Evinos is related to many ancient Greek myths, to Ancient Aetolia, as οελληνικούς μύθους, την Αρχαία Αιτωλία, την κοινωνική και οικονομική well as to the social and economic life of the area. -

Print Sheet Remote1

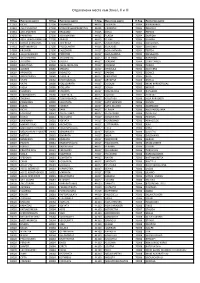

Отдалечени места към Зона I, II и III П.Код Населено място П.Код Населено място П.Код Населено място П.Код Населено място 11361 KICELI 27100 KERAMIDIA 44015 LAGKADA 70004 KSEROKABOS 12351 AGIA VARVARA 27100 MONI FRAGKOPIDIMATOS 44015 LIKORRAXI 70004 PERVOLA 13561 AGII ANARGIRI 27100 TRAGANO 44015 OKSIA 70004 PEFKOS 13672 PARNITHA 27200 AGIA MARINA 44015 PLAGIA 70004 SKAFIDIA 13679 AGIA TRIADA PARNITHAS 27200 ANALICI 44015 PLIKATI 70004 STAFRIA 13679 KSENIA PARNITHAS 27200 ASTEREIKA 44015 PIRSOGIANNI 70004 SIKOLOGOS 14451 METAMORFOSI 27200 PALEOLANTHI 44015 XIONADES 70004 SINDONIA 14568 KRIONERI 27200 PALEOXORI 44017 AGIA VARVARA 70004 TERTSA 15342 AGIA PARASKEFI 27200 PERISTERI 44017 AGIA MARINA 70004 FAFLAGKOS 18010 AGIA MARINA 27300 AGIA MAFRA 44017 VEDERIKOS 70004 XONDROS 18010 AGKISTRI 27300 KALIVIA 44017 VERENIKI 70004 CARI FORADA 18010 EGINITISSA 28080 AGIOS NIKOLAOS 44017 VROSINA 70005 AVDOU 18010 ALONES 28080 GRIZATA 44017 VRISOULA 70005 ANO KERA 18010 APONISOS 28080 DIGALETO 44017 GARDIKI 70005 GONIES 18010 APOSPORIDES 28080 ZERVATA 44017 GKRIBOVO 70005 KERA 18010 VATHI 28080 KARAVOMILOS 44017 GRANITSA 70005 KRASIO 18010 VATHI 28080 KOULOURATA 44017 DIXOUNI 70005 MONI KARDIOTISSAS 18010 VIGLA 28080 POULATA 44017 DOVLA 70005 MOXOS 18010 VLAXIDES 28080 STAVERIS 44017 DOMOLESSA 70005 POTAMIES 18010 GIANNAKIDES 28080 TZANEKATA 44017 ZALOGO 70005 SFENDILI 18010 THERMA 28080 TSAKARISIANOS 44017 KALLITHEA 70006 AGIA PARASKEFI 18010 KANAKIDES 28080 XALIOTATA 44017 KATO VERENIKI 70006 AGNOS 18010 KLIMA 28080 XARAKTI 44017 KATO ZALOGO -

Late Quaternary and Holocene Faults of the Northern Gulf of Corinth Rift, Central Greece

Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, τόμος L, σελ. 164-172 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, vol. L, p. 164-172 Πρακτικά 14ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Θεσσαλονίκη, Μάιος 2016 Proceedings of the 14th International Congress, Thessaloniki, May 2016 LATE QUATERNARY AND HOLOCENE FAULTS OF THE NORTHERN GULF OF CORINTH RIFT, CENTRAL GREECE Valkaniotis S.1 and Pavlides S.1 1Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Geology, 54124, Thessaloniki, Greece, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract New results for the recent tectonic activity in the northern part of the Gulf of Corinth rift are presented. Geological mapping and morphotectonic study re-populate the area of study with numerous active and possible active faults. The area is dominated by individual and segmented normal faults along with major structures like Marathias and Delphi-Arachova faults. The results are in accordance with recent studies that reveal a more complex and wider structure of Corinth Rift to the north. Keywords: Active Tectonics, Seismic Hazard, Normal Faults, Extension, Delphi Fault. Περίληψη Νέα δεδομένα για την πρόσφατη τεκτονική δραστηριότητα στο βόρειο τμήμα του βυθίσματος του Κορινθιακού Κόλπου παρουσιάζονται. Με βάση γεωλογική χαρτογράφηση και λεπτομερή μορφοτεκτονική μελέτη, η περιοχή μελέτης εμπλουτίζεται με πολυάριθμα ενεργά και πιθανά ενεργά ρήγματα. Στην περιοχή επικρατούν μεμονωμένα και συνενωμένα κανονικά ρήγματα, καθώς και μεγάλες κύριες τεκτονικές δομές όπως τα ρήγματα Μαραθιά και Δελφών-Αράχωβας. Ta αποτελέσματα έρχονται σε συμφωνία με πρόσφατες μελέτες που αποκαλύπτουν μια περίπλοκη και πιο ευρεία δομή της τάφρου του Κορινθιακού στα βόρεια. Λέξεις κλειδιά: Ενεργός τεκτονική, Σεισμική Επικινδυνότητα, Κανονικά Ρήγματα, Εφελκυσμός, Ρήγμα Δελφών. 1. Introduction The Gulf of Corinth Rift is a rapidly expanding intra-continental extensional rift in a W-E setting, across the Alpine formations of the External Hellenides Geotectonic units of Pindos, Vardoussia, Parnassos and Beotia (Celet, 1962; Doutsos et al., 1988; Ori, 1989; Armijo et al., 1996). -

Table of Contents

Table of contents Notes ...................................................................................................................................................8 Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................9 Foreword...........................................................................................................................................10 Greece - A Paradise of Flow ers.................................................................................................. 12 A few explanations as to why there is sometimes a question mark after some of the scientific species names, or the genus name only is g iven .....................................14 A Few Remarks on the Assortment of Orchids to be found on the Greek Mainland.. 17 Not only orchids can be found in Greece.................................................................................50 Mountain Flowers of Northern G reece.....................................................................................51 1. Falakron.................................................................................................................................51 2. Mount Pangeon.................................................................................................................. 53 3. The Voras Mountains (Kajmakcalan) - an easily accessible mountain with richly diverse flo ra ......................................................................................................................56