Religious Networks and Royal Influence In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Srirangam – Heaven on Earth

Srirangam – Heaven on Earth A Guide to Heaven – The past and present of Srirangam Pradeep Chakravarthy 3/1/2010 For the Tag Heritage Lecture Series 1 ARCHIVAL PICTURES IN THE PRESENTATION © COLLEGE OF ARTS, OTHER IMAGES © THE AUTHOR 2 Narada! How can I speak of the greatness of Srirangam? Fourteen divine years are not enough for me to say and for you to listen Yama’s predicament is worse than mine! He has no kingdom to rule over! All mortals go to Srirangam and have their sins expiated And the devas? They too go to Srirangam to be born as mortals! Shiva to Narada in the Sriranga Mahatmaya Introduction Great civilizations have been created and sustained around river systems across the world. India is no exception and in the Tamil country amongst the most famous rivers, Kaveri (among the seven sacred rivers of India) has been the source of wealth for several dynasties that rose and fell along her banks. Affectionately called Ponni, alluding to Pon being gold, the Kaveri river flows in Tamil Nadu for approx. 445 Kilometers out of its 765 Kilometers. Ancient poets have extolled her beauty and compared her to a woman who wears many fine jewels. If these jewels are the prosperous settlements on her banks, the island of Srirangam 500 acres and 13 kilometers long and 7 kilometers at its widest must be her crest jewel. Everything about Srirangam is massive – it is at 156 acres (perimeter of 10,710 feet) the largest Hindu temple complex in worship after Angkor which is now a Buddhist temple. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

23. Ranganatha Mahimai V1

Our Sincere Thanks to the following for their contributions to this ebook: Images contribution: ♦ Sriman Murali Bhattar Swami, www.srirangapankajam.com ♦ Sri B.Senthil Kumar, www.thiruvilliputtur.blogspot.com ♦ Ramanuja Dasargal, www.pbase.com/svami Source Document Compilation: Sri Anil, Smt.Krishnapriya sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Sanskrit & Tamil Paasurams text: Mannargudi Sri. Srinivasan Narayanan eBook assembly: Smt.Gayathri Sridhar, Smt.Jayashree Muralidharan C O N T E N T S Section 1 Sri Ranganatha Mahimai and History 1 Section 2 Revathi - Namperumaan’s thirunakshathiram 37 Section 3 Sri Ranganatha Goda ThirukkalyaNam 45 Section 4 Naama Kusumas of Sri Rnaganatha 87 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org PraNavAkAra Vimanam - Sri Rangam 1 sadagopan.org NamperumAL 2 . ïI>. INTRODUCTION DHYAANA SLOKAM OF SRI RANGANATHA muoe mNdhas< noe cNÔÉas< kre caé c³< suresaipvN*< , Éuj¼e zyn< Éje r¼nawm! hrerNydEv< n mNye n mNye. MukhE mandahAsam nakhE chandrabhAsam karE chAru chakram surEsApivandyam | bhujangE SayAnam bhajE RanganAtham Hareranyadaivam na manyE na manyE || sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org AZHWAR ARULICCHEYALGAL adiyEn will focus here on the 245 paasurams on Sri RanganAthA by the eleven AzhwArs. The individual AzhwAr’s paasurams are as follows: Poygai Mudal ThiruvandhAthi 1 BhUtham Second ThiruvandhAthi 4 PEy Third ThiruvandhAthi 1 Thirumazhisai Naanmukan ThiruvandhAthi 4 Thirucchanda Viruttham 10 NammAzhwAr Thiruviruttham 1 3 Thiruvaimozhi 11 PeriyAzhwAr Periya Thirumozhi 35 ANdAL NaacchiyAr Thirumozhi 10 ThiruppANar AmalanAdhi pirAn 10 Kulasekarar PerumAL Thirumozhi 31 Tondardipodi ThirumAlai 45 ThirupaLLIyezucchi 10 Thirumangai Periya Thirumozhi 58 ThirunedumthAndakam 8 ThirukkurumthAndakam 4 Siriya Thirumadal 1 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Periya Thirumadal 1 Thirumangai leads in the count of Pasurams with 72 to his credit followed by the Ranganatha Pathivrathai (Thondaradipodi) with 55 paasurams. -

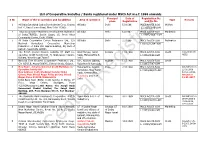

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks Registered Under MSCS Act W.E.F. 1986 Onwards Principal Date of Registration No

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks registered under MSCS Act w.e.f. 1986 onwards Principal Date of Registration No. S No Name of the Cooperative and its address Area of operation Type Remarks place Registration and file No. 1 All India Scheduled Castes Development Coop. Society All India Delhi 5.9.1986 MSCS Act/CR-1/86 Welfare Ltd.11, Race Course Road, New Delhi 110003 L.11015/3/86-L&M 2 Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development federation All India Delhi 6.8.1987 MSCS Act/CR-2/87 Marketing of India(TRIFED), Savitri Sadan, 15, Preet Vihar L.11015/10/87-L&M Community Center, Delhi 110092 3 All India Cooperative Cotton Federation Ltd., C/o All India Delhi 3.3.1988 MSCS Act/CR-3/88 Federation National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing L11015/11/84-L&M Federation of India Ltd. Sapna Building, 54, East of Kailash, New Delhi 110065 4 The British Council Division Calcutta L/E Staff Co- West Bengal, Tamil Kolkata 11.4.1988 MSCS Act/CR-4/88 Credit Converted into operative Credit Society Ltd , 5, Shakespeare Sarani, Nadu, Maharashtra & L.11016/8/88-L&M MSCS Kolkata, West Bengal 700017 Delhi 5 National Tree Growers Cooperative Federation Ltd., A.P., Gujarat, Odisha, Gujarat 13.5.1988 MSCS Act/CR-5/88 Credit C/o N.D.D.B, Anand-388001, District Kheda, Gujarat. Rajasthan & Karnataka L 11015/7/87-L&M 6 New Name : Ideal Commercial Credit Multistate Co- Maharashtra, Gujarat, Pune 22.6.1988 MSCS Act/CR-6/88 Amendment on Operative Society Ltd Karnataka, Goa, Tamil L 11016/49/87-L&M 23-02-2008 New Address: 1143, Khodayar Society, Model Nadu, Seemandhra, & 18-11-2014, Colony, Near Shivaji Nagar Police ground, Shivaji Telangana and New Amend on Nagar, Pune, 411016, Maharashtra 12-01-2017 Delhi. -

PILGRIM CENTRES of INDIA (This Is the Edited Reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the Same Theme Published in February 1974)

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA A DISTINCTIVE CULTURAL MAGAZINE OF INDIA (A Half-Yearly Publication) Vol.38 No.2, 76th Issue Founder-Editor : MANANEEYA EKNATHJI RANADE Editor : P.PARAMESWARAN PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA (This is the edited reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the same theme published in February 1974) EDITORIAL OFFICE : Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan Trust, 5, Singarachari Street, Triplicane, Chennai - 600 005. The Vivekananda Kendra Patrika is a half- Phone : (044) 28440042 E-mail : [email protected] yearly cultural magazine of Vivekananda Web : www.vkendra.org Kendra Prakashan Trust. It is an official organ SUBSCRIPTION RATES : of Vivekananda Kendra, an all-India service mission with “service to humanity” as its sole Single Copy : Rs.125/- motto. This publication is based on the same Annual : Rs.250/- non-profit spirit, and proceeds from its sales For 3 Years : Rs.600/- are wholly used towards the Kendra’s Life (10 Years) : Rs.2000/- charitable objectives. (Plus Rs.50/- for Outstation Cheques) FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTION: Annual : $60 US DOLLAR Life (10 Years) : $600 US DOLLAR VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements 1 2. Editorial 3 3. The Temple on the Rock at the Land’s End 6 4. Shore Temple at the Land’s Tip 8 5. Suchindram 11 6. Rameswaram 13 7. The Hill of the Holy Beacon 16 8. Chidambaram Compiled by B.Radhakrishna Rao 19 9. Brihadishwara Temple at Tanjore B.Radhakrishna Rao 21 10. The Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Pondicherry Prof. Manoj Das 24 11. Kaveri 30 12. Madurai-The Temple that Houses the Mother 32 13. -

Rural Fi Bank Mitra List -Tamilnadu State

RURAL FI BANK MITRA LIST -TAMILNADU STATE NAME OF THE NAME OF THE NAME OF THE NAME OF THE BRANCH BRANCH NAME OF THE VILLAGE GENDER S.NO NAME OF THE BRANCH BANK MITRA NAME MOBILE NUMBER STATE DISTRICT TALUK DIVISION CODE CATEGORY POINT (F/M) 1 TAMILNADU TIRUVANNAMALAI ARNI VILLUPURAM ARNI 1108 SEMI URBAN PUDUPATTU USHA M 7708309603 THIMMARASANAICKAN 2 TAMILNADU THENI AUNDIPATTY MADURAI AUNDIPATTY 1110 SEMI URBAN MURUGASEN V M 9600272581 UR/ 3 TAMILNADU THENI AUNDIPATTY MADURAI AUNDIPATTY 1110 SEMI URBAN POMMINAYAKANPATTI BALANAKENDRAN C M 9092183546 4 TAMILNADU DINDIGUL NEELAKOTTAI KARUR BATLAGUNDU 1112 SEMI URBAN OLD BATLAGUNDU ARUN KUMAR D M 9489832341 5 TAMILNADU ERODE BHAVANI KARUR BHAVANI 1114 SEMI URBAN ANDIKULAM RAJU T M 8973317830 6 TAMILNADU ERODE CHENNIMALAI KARUR CHENNIMALAI 1641 SEMI URBAN ELLAIGRAMAM KULANDAVEL R G M 9976118370 7 TAMILNADU ERODE CHENNIMALAI KARUR CHENNIMALAI 1641 SEMI URBAN KUPPUCHIPALAYAM SENTHIL M 8344136321 8 TAMILNADU CUDDALORE CHIDAMBARAM VILLUPURAM CHIDAMBRAM 1116 SEMI URBAN C.THANDESWARANALLURTHILAGAVATHI C F 9629502918 9 TAMILNADU DINDIGUL CHINNALAPATTI MADURAI CHINNALAPATTI 1117 SEMI URBAN MUNNILAKOTTAI NAGANIMMI F 8883505650 10 TAMILNADU THENI UTHAMAPALAYAM MADURAI CHINNAMANUR 1118 SEMI URBAN PULIKUTHI ESWARAN M 9942158538 11 TAMILNADU THENI CHINNAMANUR MADURAI CHINNAMANUR 1118 SEMI URBAN MARKEYANKOTTAI BHARATHI V F 9940763670 12 TAMILNADU TIRUPPUR DHARAPURAM KARUR DHARAPURAM 1126 SEMI URBAN MADATHUPALAYAM GANDHIMATHI A F 9843912225 13 TAMILNADU TIRUPPUR DHARAPURAM KARUR DHARAPURAM 1126 SEMI URBAN -

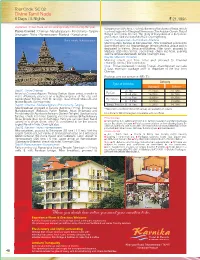

Car Package New Size 1

Tour Code: SC 02 Divine Tamil Nadu 6 Days / 5 Nights ` 21,199/- Departure :These tours can be arranged any time during the year. Kanyakumari (325 kms / 7.5 hrs), the end of land area of India, which Places Covered : Chennai - Mahabalipuram - Pondicherry - Tanjore - is a meeting point of the great three seas (The Arabian Ocean, Bay of Srirangam - Trichy - Rameswaram - Madurai - Kanyakumari. Bengal and Indian Ocean). The glory of Kanyakumari is its Sunrise and Sunset. Visit Vivekananda Rock. Overnight stay. Shore Temple, Mahabalipuram Day 05 : Kanyakumari - Suchindram - Madurai Morning enjoy Sunrise at Kanyakumari. After breakfast, proceed to Suchindram and visit Thanumalayan Temple which is unique as it is dedicated to Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma. After lunch, proceed to Madurai. (250 kms / 6 hrs). Upon arrival, check into hotel. Evening visit the famous Meenakshi Temple. Overnight stay. Day 06 : Madurai - Chennai Morning check out from hotel and proceed to Chennai ( 460 kms. / 8 hrs.) Tour concludes. Note : Those interested in visiting Tirupati - Kanchipuram can take 2 days extension package prior to departure of the tour from Chennai. Package cost per person in INR ( ` ) Category Type of Vehicles Standard Deluxe Day 01 : Arrive Chennai 2 Pax 21,199/- 23,799/- By Car Arrival at Chennai Airport / Railway Station. Upon arrival, transfer to 3 - 4 Pax 16,299/- 18,799/- Hotel. Afternoon, proceed on a sightseeing tour of the city, visit 4 - 5 Pax Kapaleshwar Temple, Fort St. George, Government Museum and By Innova 16,699/- 19,299/- Marina Beach. Overnight stay. 6 - 7 Pax 12,299/- 14,899/- Day 02 : Chennai - Mahabalipuram - Pondicherry - Tanjore Tempo Traveller 8 - 9 Pax 11,299/- 14,199/- After breakfast, proceed to Tanjore (340 kms / 7 hrs), Enroute visit * Fares from 21st December to 5th January are available on request. -

Dance Imagery in South Indian Temples : Study of the 108-Karana Sculptures

DANCE IMAGERY IN SOUTH INDIAN TEMPLES : STUDY OF THE 108-KARANA SCULPTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bindu S. Shankar, M.A., M. Phil. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Susan L. Huntington, Adviser Professor John C. Huntington Professor Howard Crane ----------------------------------------- Adviser History of Art Graduate Program Copyright by Bindu S. Shankar 2004 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the theme of dance imagery in south Indian temples by focusing on one aspect of dance expression, namely, the 108-karana sculptures. The immense popularity of dance to the south Indian temple is attested by the profusion of dance sculptures, erection of dance pavilions (nrtta mandapas), and employment of dancers (devaradiyar). However, dance sculptures are considered merely decorative addtitions to a temple. This work investigates and interprets the function and meaning of dance imagery to the Tamil temple. Five temples display prominently the collective 108-karana program from the eleventh to around the 17th century. The Rajaraja Temple at Thanjavur (985- 1015 C.E.) displays the 108-karana reliefs in the central shrine. From their central location in the Rajaraja Temple, the 108 karana move to the external precincts, namely the outermost gopura. In the Sarangapani Temple (12-13th century) at Kumbakonam, the 108 karana are located in the external façade of the outer east gopura. The subsequent instances of the 108 karana, the Nataraja Temple at Cidambaram (12th-16th C.E.), the Arunachalesvara Temple at Tiruvannamalai (16th C.E.), and the Vriddhagirisvara Temple at Vriddhachalam (16th-17th C.E.), ii also use this relocation. -

SIEMENS LIMITED List of Outstanding Warrants As on 18Th March, 2020 (Payment Date:- 14Th February, 2020) Sr No

SIEMENS LIMITED List of outstanding warrants as on 18th March, 2020 (Payment date:- 14th February, 2020) Sr No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A P RAJALAKSHMY A-6 VARUN I RAHEJA TOWNSHIP MALAD EAST MUMBAI 400097 A0004682 49.00 2 A RAJENDRAN B-4, KUMARAGURU FLATS 12, SIVAKAMIPURAM 4TH STREET, TIRUVANMIYUR CHENNAI 600041 1203690000017100 56.00 3 A G MANJULA 619 J II BLOCK RAJAJINAGAR BANGALORE 560010 A6000651 70.00 4 A GEORGE NO.35, SNEHA, 2ND CROSS, 2ND MAIN, CAMBRIDGE LAYOUT EXTENSION, ULSOOR, BANGALORE 560008 IN30023912036499 70.00 5 A GEORGE NO.263 MURPHY TOWN ULSOOR BANGALORE 560008 A6000604 70.00 6 A JAGADEESWARAN 37A TATABAD STREET NO 7 COIMBATORE COIMBATORE 641012 IN30108022118859 70.00 7 A PADMAJA G44 MADHURA NAGAR COLONY YOUSUFGUDA HYDERABAD 500037 A0005290 70.00 8 A RAJAGOPAL 260/4 10TH K M HOSUR ROAD BOMMANAHALLI BANGALORE 560068 A6000603 70.00 9 A G HARIKRISHNAN 'GOKULUM' 62 STJOHNS ROAD BANGALORE 560042 A6000410 140.00 10 A NARAYANASWAMY NO: 60 3RD CROSS CUBBON PET BANGALORE 560002 A6000582 140.00 11 A RAMESH KUMAR 10 VELLALAR STREET VALAYALKARA STREET KARUR 639001 IN30039413174239 140.00 12 A SUDHEENDHRA NO.68 5TH CROSS N.R.COLONY. BANGALORE 560019 A6000451 140.00 13 A THILAKACHAR NO.6275TH CROSS 1ST STAGE 2ND BLOCK BANASANKARI BANGALORE 560050 A6000418 140.00 14 A YUVARAJ # 18 5TH CROSS V G S LAYOUT EJIPURA BANGALORE 560047 A6000426 140.00 15 A KRISHNA MURTHY # 411 AMRUTH NAGAR ANDHRA MUNIAPPA LAYOUT CHELEKERE KALYAN NAGAR POST BANGALORE 560043 A6000358 210.00 16 A MANI NO 12 ANANDHI NILAYAM -

Activity Report: 2017 - 2018 #10/23, Sharada, Thiruvengadam Street, R

A unit of Sringeri Sri Sharada Peetham Charitable Trust Activity Report: 2017 - 2018 #10/23, Sharada, Thiruvengadam Street, R. A. Puram, Chennai - 600 028 V-Excel Educational Trust Activity Report: 2017-18 Table of Contents Significant Events ....................................................................................................................................... 2 International Paper Presentation .......................................................................................................... 2 The Lion King .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Awards and Recognition ........................................................................................................................ 3 Blue Sky Choir ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Tarang .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Wipro Marathon .................................................................................................................................... 4 Media Interactions ................................................................................................................................. 4 Resource Development ............................................................................................................................. -

Infrastructure Development Investment Program for Tourism, Tamil Nadu (IDIPT-TN), Project 2

Infrastructure Development Investment Program for Tourism, Tamil Nadu (IDIPT-TN), Project 2 PROCUREMENT PLAN Basic Data Project Name: Infrastructure Development Investment Program for Tourism– Project 2 Country: India Executing Agency: Department of Tourism & Culture, Government of Tamil Nadu Loan Amount: US$ 20.56 million (Tranche-1) Loan Number: 2833-IND Date of First Procurement Plan: 31 August 2011 Date of this Revised Procurement Plan: December 09, 2013 A. Process Thresholds, Review and Procurement Plan 1. Project Procurement Thresholds 2. Except as Asian Development Bank (ADB) may otherwise agree, the following process thresholds shall apply to procurement of goods and works. Procurement of Goods and Works Method Threshold International Competitive Bidding (ICB) for Works1 $ 40,000,000 and above International Competitive Bidding for Goods1 $1,000,000 and above National Competitive Bidding (NCB) for Works1 Below $ 40,000,000 National Competitive Bidding for Goods1 Below $1,000,000 Shopping for Works Below $100,000 Shopping for Goods Below $100,000 1 3. ADB Prior or Post Review 4. Except as ADB may otherwise agree, the following prior or post review requirements apply to the various procurement and consultant recruitment methods used for the project. Procurement Method Prior or Post Comments Procurement of Goods and Works ICB Works Prior ICB Goods Prior NCB Works Prior Only for the first two bid documents and bid evaluation reports from PMU and each PIU would be reviewed by ADB. NCB Goods Prior Only for the first two bid documents and bid evaluation reports from PMU and each PIU would be reviewed by ADB. Shopping for Works Post Shopping for Goods Post Recruitment of Consulting Firms Quality- and Cost-Based Selection (QCBS) Prior Quality-Based Selection (QBS) Prior Other selection methods: Consultants Qualifications (CQS), Least-Cost Prior Selection (LCS), Fixed Budget (FBS), and Single Source (SSS) Recruitment of Individual Consultants Individual Consultants Prior ICB = international competitive bidding, NCB = national competitive bidding 2 5. -

Kumbakonam: the Ritual Topography of a Whole of India

ARCHAEOLO the case of the Mahamakam tank, to the Kumbakonam: the ritual topography of a whole of India. sacred and royal city of South India Legendary origins ofKumbakonam Our knowledge of the earliest history of Vivek Nanda Kumbakonam comes from texts and very South India is renowned worldwide fo r the architectural splen little archaeological work has been con dour of its temples and the elaborate sculpture that adorns ducted so far. The city was referred to as Kudandai in the corpus ofTamil literature them, but their symbolism, still ritually enacted today, is less known as the Sangam, which dates to the well understood outside India. Complex interrelationships of first three centuries AD. However, in early art, architecture and ritual are expressed in the evolution, religious works dedicated to the god Shiva through the past thousand years, of the topography of one of the (the Shaiva corpus) it was called Kuda most important of the temple cities. mukku (literally, the mouth or spout of the pot), probably the antecedent of its present name Kumbakonam which first appears in or over a millennium Kumba city's present commercial prosperity. a fourteenth-century inscription. The pot konam has been a sacred centre Throughout its historical evolution, it has motif, evidently significant in the histori of Hindu pilgrimage. It differs also been a seat of scholarship - the bril cal evolution of the place name, may sim Ffrom other temple cities of south liance and fame of its scholars being ply refer to the town's wedge shape and ern India in the diversity of the widely recognized through to the early location at the point where the Kaveri religious traditions manifested in its archi twentieth century, when it was known as bifurcates in its delta from the Arasalar tecture and celebrated in elaborate cycles the "Cambridge of South India".