Framing of the Nuclear Discourse in South Africa: an Institutional Economics Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keep Nuclear Power out of the Cdm (Clean Development Mechanism)

KEEP NUCLEAR POWER OUT OF THE CDM (CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM) Nuclear Power Contradicts Clean Development: Too Little, Too Late, Too Expensive Too Dangerous The Following NGOs Have Joined the Call to Remove "Nuclear Activities" as an Option in the CDM as of 10 December 2008 Women in Europe for a Common Future International Forum on Globalization Greenpeace World Information Service on Energy (WISE) Ecodefense Russia Friends of the Earth International Nuclear Information and Resource Service (NIRS) 8th Day Center for Justice Illinois,USA ACDN (Action des Citoyens pour le Désarmement Nucléaire France AERO—Alternative Energy Resources Organization Montana, USA AGAT Kyrgyzstan Alianza por la Justicia Climatica Chile Alliance for Affordable Energy Louisiana,USA Alliance for Sustainable Communities-Lehigh Valley, Inc. Pennsylvania, USA ALMA-RO Association Romania Alternativa Verda ONG (Green Alternative) Spain/Catalunya Amigos da Terra - Amazônia Brasileira Brazil Amigos de la Tierra/FOE Spain Spain Amis de la Terre - Belgique Belgium Anti Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia Australia Anti Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia (ANAWA) Australia APROMAC - Environment Protection Association Brazil APROMAC - Environment Protection Association Brazil Arab Climate Alliance Lebanon Arizona Safe Energy Coalition Arizona, USA Artists for a Clean Future Asociación Contra Contaminación Ambiental de E.Echeverría Argentina Atomstopp Austria Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) Australia Banktrack Netherlands Bellefonte Efficiency and Sustainaibity -

Building on The

wmm mmmsm BUILDING ON THE Towards a post-apartheid constitution IN THIS ISSUE Metal wage talks Militarisation • Apartheid death squads Editorial here is a sense in which government's closure of one newspaper, Tand threatened banning of a number of other publications, is justi fied. This is not because those publications are necessarily guilty of biased or inaccurate journalism, or even because they are in contravention of the over 100 statutes which limit what may be published. Rather, it is because any government which has as much to hide as South Africa's rulers must fear all but the most tame sections of the media. Nearly half of all the editions of Work In Progress produced over ten years were banned under the Publications Act. Yet not once was it suggested that inaccuracy or false information was the reason for banning. In warning Work In Progress that action against the magazine was being contemplated, Stoffel Botha claims to have looked at 24 articles contained in two editions of the magazine. Yet in not one case does he claim that information in an article was false. The conclusion is clear: publications like Work In Progress face closure or pre-publication censorship because of the accuracy of their reporting and analysis. • When an attorney-general declines to prosecute soldiers who kidnap, assault and threaten with death a political activist because the soldiers were acting in terms of emergency regulations; • when a head of state stops the trial of soldiers accused of murdering a Swapo member at a political meeting because -

Registration 6.30 Pm

• Laurie Nathan, National Organiser, End 2pm - 6pm : Registration Conscription Campaign. "ECC : where we come from, what we stand for and why we call for peace." • Jennifer Fergusson : Music and poetry. Registration for the festival costs R40.00 for • Stan James : Music. salaried individuals and R30.00 for others. These amounts are requested to help defray some of the festival expenses. If you are intending to come for only one day, or a part of one day, you are requested 9.30 pm : Concert to pay a R5,00 registration fee for that day. Stop the Call-up! Subsidy forms are available on request but subsidies cannot be guaranteed. • Facts • Rapula • The Softies • Nude Red 6.30 pm : Public meeting • Mapansula World in conflict — the need for peace C h a ir: Benita Pavlecevic, Chairperson, End Conscription Committee, Johannesburg. • Cardinal Arns, Archbishop of Sao Paulo, Brazil, internationally recognised as the leading critic of the excesses of Brazil's mil itary rulers. "The Latin American people's pursuit of justice". • Bishop Desmond Tutu, Nobel Peace Laureate. "Conflict in Southern Africa : the South African Defence Force as aggressor and agent of destabilization" • Dr Beyers Naude, General Secretary, South African Council of Churches. "Civil war in South Africa : the need for justice, the requirements for peace". • Sir Richard Luyt, Civil Rights League. Local and international messages of sup port. his morning is taken up by options. The first set begins a t 9.00 am and the Tsecond at 11.00 am. Each set contains four options. You can choose to go to one in each set. -

the "Vaz Diaries" Are Captured Clearly Revealing That the SADF Was

- The "Vaz diaries" are captured clearly revealing that the SADF was continuing to support the MNR in Mozambique, despite the Nkomati Accord.Shortly afterwards the Head of the Defence Force, General Constand Viljoen, resigns. The ECC establishes branches in six centres with three more being in the process of formation. - In January 1885 7589 conscripts (including 6 000 students who were automatically deferred) fail to turn up for their national service. - Approximately 25 percent of people fail to turn up for their SADF camps. - An estimated 7 000 objectors are living overseas. - Between July 1984 and December 1985 758 people apply to the Board for Religious Objection. 421 are granted full objector status and 11 are refused. - In November 1985 ECC member Harald Winkler is refused by the Board for Religious Objection because they find he is not a "universal religious pacifist". - In August 1985 Alan Dodson, a Pietermaritzburg law graduate, is fined R600 for refusing to enter a township while on an SADF camp. - 26 895 people emigrate from South Africa between January and November 1985.- an increase of over 40% from 1984. - New powers of arbitary detention given to SADF members. - By the end of 1985 an estimated 1 000 Deople have died in the township conflict - moat through the actions of the security forces. - The ANC increases its attacks by 309 percent during 1985. 1986: The blokade of Lesotho leads to the downfall of the Maseru government in a military coup. - Philip Wilkenson, a Port Elizabeth butcher, becomes the 12th objector to be refused by the Board for Religious Objection and announces his intention of objecting on political grounds. -

The Social Shaping of Nuclear Energy Technology in South Africa

WIDER Working Paper 2016/19 The social shaping of nuclear energy technology in South Africa Britta Rennkamp1 and Radhika Bhuyan2 April 2016 In partnership with Abstract: This paper analyses the question why the South African government intends to procure nuclear energy technology, despite affordable and accessible fossil and renewable energy alternatives. We analyse the social shaping of nuclear energy technology based on the statements of political actors in the public media. We combine a discourse network analysis with qualitative analysis to establish the coalitions in support and opposition of the programme. The central arguments in the debate are cost, safety, job creation, the appropriateness of nuclear energy, emissions reductions, transparency, risks for corruption, and geopolitical influences. The analysis concludes that the nuclear programme is not primarily about generating electricity, as it creates tangible benefits for the coalition of supporters. Keywords: nuclear energy, energy policy, science and technology policy, discourse network analysis, South Africa JEL classification: O14, Q48, O33, O55 Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank all colleagues, unknown reviewers, and interviewees who supported our work on this paper. Thanks to the interviewees for the trust of sharing your insights. Thanks to the reviewers and colleagues for the helpful comments on previous versions of this paper and constructive comments during two seminars at the Universities of the Witwatersrand and Cape Town. Thanks to UNU-WIDER and the Volkswagen Foundation, Compagnia di San Paolo, as well as Riksbankens Jubileumsfond under the project, ‘Climate Change Mitigation and Poverty Reduction’ for support. 1 Energy Research Centre and African Climate and Development Initiative, University of Cape Town, South Africa, corresponding author: [email protected]; 2 Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection, Johannesburg, South Africa. -

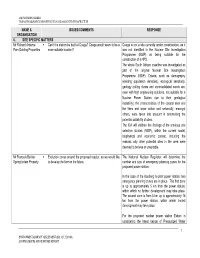

Issues and Response Report – June 2007

ESKOM HOLDINGS LIMITED PROPOSED ESKOM NUCLEAR POWER STATION AND ASSOCIATED INFRASTRUCTURE NAME & ISSUES/COMMENTS RESPONSE ORGANISATION 6. SITE SPECIFIC MATTERS Mr Richard Arderne Can’t the station be built at Coega? Coega would seem to be a Coega is not a site currently under consideration, as it Pam Golding Properties more suitable location? was not identified in the Nuclear Site Investigation Programme (NSIP) as being suitable for the construction of a NPS. The whole South African coastline was investigated as part of the original Nuclear Site Investigation Programme (NSIP). Criteria, such as demography (existing population densities), ecological sensitivity, geology (rolling dunes and unconsolidated sands are, even with high engineering solutions, not suitable for a Nuclear Power Station due to their geological instability), the characteristics of the coastal area and the tides and wave action and seismicity, amongst others, were taken into account in determining the potential suitability of sites. The EIA will validate the findings of the previous site selection studies (NSIP), within the current social, biophysical and economic context, including the reasons why other potential sites in the area were deemed to be less or unsuitable. Mr Francois Bekker Exclusion zones around the proposed reactor, as we would like The National Nuclear Regulator will determine the Springfontein Property to develop the farm in the future. number and size of emergency planning zones for the proposed power station. In the case of the Koeberg nuclear power station, two emergency planning zones are in place. The first zone is up to approximately 5 km from the power station, within which no further development may take place. -

Southscan Subscription Dept, at Its Heart Lies a of Security Structures Police

E EPISCOPAL CHUR.CHPEOPLE for a ~REE SOUTHERN AFRICA C 339 Lafayette Street, New York, N.Y. 10012·2725 S (212) 4n -e066 FAX: (212) 979 -1013 A #101 1 August 1990 SOUTH AFRICA - EMERGENCE AND REPRESSION SOUTHSA Bulletin of Southern AfricanCANAffairs f-.&l Vol. 5 No. 28 ~. 20 July 1990 -----cYJ---------.:.-- Strtkes and squatter protests spread throughout countIy CAPE TOWNI As the The UDF vice. Uri. week thousands The bulldozer dro~e government and the ofclothing workers took .traicht at them and president in the We.t tben eraehed into ANC gear up for the ern Cape, Dullah part in a demonstration 10 .upport of union.' their houaee. next round of talks Omar, said that the aimedatpreparingfor demanil for workera' Pa-inc pollee can UDF was concerned rights to be guaranteed were lItoned before negotiations, ma.s that the land was not MCUrity foreee rU'ed based organi.ations being ul8d and saw no in a new constitution. tearp.into the are taking militant More than 60,000 ancr:r crowd. reason why people workersjoined hands to action, wrUu a corre desperate for homes Ancry youth then spondent here. should not OCICupy the form a human chain moved into the A spate of strikes area. along main road. in adJolninc euburb of and squatter prote.ts Cape Town on newho~and has rocked South Af District Six haal Wedneaday. Similar attempted to torch imense emotional si - demon.trations took the hom..of Dobeon rica this month and niCicance for blac\ ville councUlorw. more seem likely to Capetonians as a sym- part in other major After their ..ttlement follow. -

Contemporary South African Environmental Response: An

\ CONTEMPORARY SOUTH AFRICAN ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSE: AN HISTORICAL AND SOCIO-POLITICAL EVALUATION, WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE ·To BLACKS. by FARIEDA KHAN University of Cape Town Submitted to the University of Cape Town in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Environmental Science. March, 1990. The University of Cape Town has been given the right to reproduce this thesis in whole or In part. Copyright is held by the author• .. , iS M I )Cf,O r The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ABSTRACT The - impress of history has been particularly profound in the sphere of environmental perception, in that South Africans, both black and white, have had their notions of the environment shaped by the political forces of the past. Accordingly, this study is placed within the context of historical geography, as its open ended techniques and multi-disciplinary approach is regarded as the most appropriate way of undertaking a study which crosses both historical and environmental boundaries. A contention fundamental to this study, is that South African environmental awareness and knowledge is at a fairly low level and that black environmental interest and concern in particular, ranges from apathy to outright hostility. It is further contended that the attainment of mass environmental literacy is essential for the success of the environmental movement in this country and that this in turn, is dependent on the adoption of a strategy incorporating an integrated hi~torical, social and political perspective. -

African Security Review, Vol 17 No 4

Institute for Security Studies African Security Review African Security Review vol 17 no 4 December 2008 2008 Editor Deane-Peter Baker Editorial Board Festus Aboagye Hiruy Amanuel Annie Chikwanha Jakkie Cilliers Anton du Plessis Peter Edupo Peter Gastrow Charles Goredema Paul-Simon Handy Guy Lamb Len le Roux Prince Mashele Kenneth Mpyisi Augusta Muchai Naison Ngoma Hennie van Vuuren Abstracts v Features Zimbabwe’s 2008 elections and their implications for Africa 2 Simon Badza Chinese arms destined for Zimbabwe over South African territory: The R2P norm and the role of civil society 17 Max du Plessis Elections and confl ict resolution: The West African experience 30 Ismaila Madior Fall The implementation of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance 43 Ibrahima Kane ‘God willing, I will be back’: Gauging the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s capacity to deter economic crimes in Liberia 64 Rosalia de la Cruz Gitau Africa Watch Angola’s legislative elections: Time to deliver on peace dividends 80 Paula Cristina Roque Stabilising the Eastern DRC 84 Henri Boshoff CONTENTS Essays The conundrum of conditions for intervention under article 4(h) of the African Union Act 90 Dan Kuwali Terror in the backyard: Domestic terrorism in Africa and its impact on human rights 112 Cephas Lumina Nuclear Africa: Weapons, power and proliferation 133 Gavin Cawthra and Bjoern Moeller Complementarity and Africa: The promises and problems of international criminal justice 154 Max du Plessis Commentaries Kenya: After the crisis, lessons abandoned -

Mary Burton - Black Sash

We, South Africans, reject conscription ™"“ ~ MARY BURTON - BLACK SASH ... ............... - I support the declaration to End Conscription because I believe that all young South Africans should be allowed the right to choose how they wi11 work for justice and peace in their count ry. I do not believe that service in the SADF is the road to the goal shared by many : 'a united South Africa where true democracy and the protection oh human rights offer a better chance of achieving justice and a lasting peace. REV DOUG BAX - CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH, RONDEBOSCH I support the E.C.C. because: the State would not need to conscript for a justifiable war; the State has no right to conscript for an unjust- i f i a b1e wa r. Many young South Africans utterly reject being cons cripted into an army that is being used to deal with what - in the final analysis is a political problem: the protests of the excluded and oppressed. To be sure military forces may contain these protests for a time, but to suppose that institutionalised vio lence can transform South Africa into a stable, decent and democratic society is absurd. It is to the credit of those working to end conscription that they realise this, and rather than being hounded , as traitors, 1 join with many other South Africans in praising them for their vision and compassion. SIR RICHARD LUYT - EX-VICE CHANCELLOR UCT Conscription for all the population of a country would be unacceptable to me in most circumstances; conscription of an ethnic section of the population, as in South Africa, is unacceptable in all circ umstances . -

43737 25-09 Legala

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA September Vol. 663 Pretoria, 25 2020 September No. 43737 PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 43737 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 43737 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 25 SEPTEMBER 2020 IMPORTANT NOTICE OF OFFICE RELOCATION Private Bag X85, PRETORIA, 0001 149 Bosman Street, PRETORIA Tel: 012 748 6197, Website: www.gpwonline.co.za URGENT NOTICE TO OUR VALUED CUSTOMERS: PUBLICATIONS OFFICE’S RELOCATION HAS BEEN TEMPORARILY SUSPENDED. Please be advised that the GPW Publications office will no longer move to 88 Visagie Street as indicated in the previous notices. The move has been suspended due to the fact that the new building in 88 Visagie Street is not ready for occupation yet. We will later on issue another notice informing you of the new date of relocation. We are doing everything possible to ensure that our service to you is not disrupted. As things stand, we will continue providing you with our normal service from the current location at 196 Paul Kruger Street, Masada building. Customers who seek further information and or have any questions or concerns are free to contact us through telephone 012 748 6066 or email Ms Maureen Toka at [email protected] or cell phone at 082 859 4910. Please note that you will still be able to download gazettes free of charge from our website www.gpwonline.co.za. -

4006 ISS ASR 17.4.Indd

Institute for Security Studies African Security Review African Security Review vol 17 no 4 December 2008 2008 Editor Deane-Peter Baker Editorial Board Festus Aboagye Hiruy Amanuel Annie Chikwanha Jakkie Cilliers Anton du Plessis Peter Edupo Peter Gastrow Charles Goredema Paul-Simon Handy Guy Lamb Len le Roux Prince Mashele Kenneth Mpyisi Augusta Muchai Naison Ngoma Hennie van Vuuren Abstracts v Features Zimbabwe’s 2008 elections and their implications for Africa 2 Simon Badza Chinese arms destined for Zimbabwe over South African territory: The R2P norm and the role of civil society 17 Max du Plessis Elections and confl ict resolution: The West African experience 30 Ismaila Madior Fall The implementation of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance 43 Ibrahima Kane ‘God willing, I will be back’: Gauging the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s capacity to deter economic crimes in Liberia 64 Rosalia de la Cruz Gitau Africa Watch Angola’s legislative elections: Time to deliver on peace dividends 80 Paula Cristina Roque Stabilising the Eastern DRC 84 Henri Boshoff CONTENTS Essays The conundrum of conditions for intervention under article 4(h) of the African Union Act 90 Dan Kuwali Terror in the backyard: Domestic terrorism in Africa and its impact on human rights 112 Cephas Lumina Nuclear Africa: Weapons, power and proliferation 133 Gavin Cawthra and Bjoern Moeller Complementarity and Africa: The promises and problems of international criminal justice 154 Max du Plessis Commentaries Kenya: After the crisis, lessons abandoned