4006 ISS ASR 17.4.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 13, 2016 Volume Xiv, Issue 12

THE JAMESTOWN FOUNDATION JUNE 13, 2016 VOLUME XIV, ISSUE 12 p.1 p.3 p.6 p.8 Alexander Sehmer Abubakar Siddique Jessica Moody Wladimir van Wilgenburg BRIEFS Taliban Victories in The Niger Delta U.S. Backing Gives Helmand Province Avengers: A New Kurds Cover for United Prove Test for Afghan Threat to Oil Produc- Federal Region in Government ers in Nigeria Northern Syria LIBYA: CLOSING IN ON ISLAMIC STATE’S STRONG- battle ahead. IS is thought to have heavily fortified Sirte. HOLD The advancing forces will face thousands of fighters and potentially suicide bombers and Improvised Explosive Alexander Sehmer Devices (IEDs). There also remains the question of just how unified an assault will be. The Misratan-led forces Libyan forces have had a run of luck against Islamic have been brought together under the Bunyan Marsous State (IS) fighters in recent weeks, with two separate Operations Room (BMOR), established by Prime Minis- militias capturing several towns and closing in on the ter Faiez Serraj, head of the Government of National extremists’ stronghold of Sirte. Accord (GNA) (Libya Herald, June 8). According to BMOR, they are working with the PFG. Amid Libya’s The Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG), the unit set up to fractious politics, however, it is unlikely to be that sim- protect Libya’s oil installations, took control of the town ple. of Ben Jawad on May 30 and moved on to capture Naw- filiyah, forcing IS fighters back towards Sirte (Libya Her- The PFG is not a natural ally for the Misratans, and the ald, June 1). -

Norm to the International Community's Response to the Humanitarian

Application of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ norm to the International Community’s Response to the Humanitarian Crises in Zimbabwe and Darfur. by Patrick Dzimiri Student Number: 28457600 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree: Doctor Philosophiae (DPhil) International Relations in the Department of Political Sciences at the UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES SUPERVISOR: DR YK. SPIES February 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation submitted for Doctor Philosophiae (DPhil) International Relations at the University of Pretoria, apart from the help of the recognised, is my own work and has not been formerly submitted to another university for a degree. Patrick Dzimiri February 2016. Signature………………………. Date……………………… i ABSTRACT The Responsibility to Protect (RtoP) is an interdisciplinary normative framework that reconceptualises state sovereignty as a responsibility rather than a right. It obliges states to protect their people from humanitarian catastrophe, and in the event of state failure or unwillingness to heed this responsibility, requires of the broader international community to assume the residual duty to protect. When the principles of RtoP were endorsed by world leaders at the United Nations’ 2005 World Summit, it seemed as though the normative regime was gaining currency in international relations. However, the operationalization of RtoP continued to be dogged by controversy and conceptual ambiguity. This prompted UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon in January 2009 to appeal to the international community to strengthen the “doctrinal, policy and institutional life” of the norm. This study responds to Ban’s call and seeks to complement efforts of scholars across the world to refine the conceptual parameters of RtoP. -

The Gordian Knot: Apartheid & the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order, 1960-1970

THE GORDIAN KNOT: APARTHEID & THE UNMAKING OF THE LIBERAL WORLD ORDER, 1960-1970 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Ryan Irwin, B.A., M.A. History ***** The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Peter Hahn Professor Robert McMahon Professor Kevin Boyle Professor Martha van Wyk © 2010 by Ryan Irwin All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the apartheid debate from an international perspective. Positioned at the methodological intersection of intellectual and diplomatic history, it examines how, where, and why African nationalists, Afrikaner nationalists, and American liberals contested South Africa’s place in the global community in the 1960s. It uses this fight to explore the contradictions of international politics in the decade after second-wave decolonization. The apartheid debate was never at the center of global affairs in this period, but it rallied international opinions in ways that attached particular meanings to concepts of development, order, justice, and freedom. As such, the debate about South Africa provides a microcosm of the larger postcolonial moment, exposing the deep-seated differences between politicians and policymakers in the First and Third Worlds, as well as the paradoxical nature of change in the late twentieth century. This dissertation tells three interlocking stories. First, it charts the rise and fall of African nationalism. For a brief yet important moment in the early and mid-1960s, African nationalists felt genuinely that they could remake global norms in Africa’s image and abolish the ideology of white supremacy through U.N. -

South Africa: Afrikaans Film and the Imagined Boundaries of Afrikanerdom

A new laager for a “new” South Africa: Afrikaans film and the imagined boundaries of Afrikanerdom Adriaan Stefanus Steyn Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Social Anthropology in the faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Bernard Dubbeld Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology December 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract The Afrikaans film industry came into existence in 1916, with the commercial release of De Voortrekkers (Shaw), and, after 1948, flourished under the guardianship of the National Party. South Africa’s democratic transition, however, seemed to announce the death of the Afrikaans film. In 1998, the industry entered a nine-year slump during which not a single Afrikaans film was released on the commercial circuit. Yet, in 2007, the industry was revived and has been expanding rapidly ever since. This study is an attempt to explain the Afrikaans film industry’s recent success and also to consider some of its consequences. To do this, I situate the Afrikaans film industry within a larger – and equally flourishing – Afrikaans culture industry. -

THE UNITED STATES and SOUTH AFRICA in the NIXON YEARS by Eric J. Morgan This Thesis Examines Relat

ABSTRACT THE SIN OF OMISSION: THE UNITED STATES AND SOUTH AFRICA IN THE NIXON YEARS by Eric J. Morgan This thesis examines relations between the United States and South Africa during Richard Nixon’s first presidential administration. While South Africa was not crucial to Nixon’s foreign policy, the racially-divided nation offered the United States a stabile economic partner and ally against communism on the otherwise chaotic post-colonial African continent. Nixon strengthened relations with the white minority government by quietly lifting sanctions, increasing economic and cultural ties, and improving communications between Washington and Pretoria. However, while Nixon’s policy was shortsighted and hypocritical, the Afrikaner government remained suspicious, believing that the Nixon administration continued to interfere in South Africa’s domestic affairs despite its new policy relaxations. The Nixon administration concluded that change in South Africa could only be achieved through the Afrikaner government, and therefore ignored black South Africans. Nixon’s indifference strengthened apartheid and hindered liberation efforts, helping to delay black South African freedom for nearly two decades beyond his presidency. THE SIN OF OMMISSION: THE UNITED STATES AND SOUTH AFRICA IN THE NIXON YEARS A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Eric J. Morgan Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2003 Advisor __________________________________ (Dr. Jeffrey P. Kimball) Reader ___________________________________ (Dr. Allan M. Winkler) Reader ___________________________________ (Dr. Osaak Olumwullah) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . iii Prologue The Wonderful Tar Baby Story . 1 Chapter One The Unmovable Monolith . 3 Chapter Two Foresight and Folly . -

Africa Report

PROJECT ON BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Africa April to June 2008 Volume: 1 Reports for the period April to May 2008 Principal Investigator: Prof. Dr. Ijaz Shafi Gilani Contributors Abbas S Lamptey Snr Research Associate Reports on Sub-Saharan AFrica Abdirisak Ismail Research Assistant Reports on East Africa INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Asia April to June 2008 Reports for the period April to May 2008 Volume: 1 Department of Politics and International Relations International Islamic University Islamabad 2 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Africa 2008 Table of contents Reports for the month of April Week-1 April 01, 2008 05 Week-2 April 08, 2008 63 Week-3 April 15, 2008 120 Week-4 April 22, 2008 185 Week-5 April 29, 2008 247 Reports for the month of May Week-1 May 06, 2008 305 Week-2 May 12, 2008 374 Week-3 May 20, 2008 442 Country profiles Sources 3 4 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD Weekly Presentation: April 1, 2008 Sub-Saharan Africa Abbas S Lamptey Period: From March 23 to March 29 2008 1. CHINA -AFRICA RELATIONS WEST AFRICA Sierra Leone: Chinese May Evade Govt Ban On Logging: Concord Times (Freetown):28 March 2008. Liberia: Chinese Women Donate U.S. $36,000 Materials: The NEWS (Monrovia):28 March 2008. Africa: China/Africa Trade May Hit $100bn in 2010:This Day (Lagos):28 March 2008. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project STEVE McDONALD Interviewed by: Dan Whitman Initial Interview Date: August 17, 2011 Copyright 2018 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Education MA, South African Policy Studies, University of London 1975 Joined Foreign Service 1975 Washington, DC 1975 Desk Officer for Portuguese African Colonies Pretoria, South Africa 1976-1979 Political Officer -- Black Affairs Retired from the Foreign Service 1980 Professor at Drury College in Missouri 1980-1982 Consultant, Ford Foundation’s Study 1980-1982 “South Africa: Time Running Out” Head of U.S. South Africa Leadership Exchange Program 1982-1987 Managed South Africa Policy Forum at the Aspen Institute 1987-1992 Worked for African American Institute 1992-2002 Consultant for the Wilson Center 2002-2008 Consulting Director at Wilson Center 2009-2013 INTERVIEW Q: Here we go. This is Dan Whitman interviewing Steve McDonald at the Wilson Center in downtown Washington. It is August 17. Steve McDonald, you are about to correct me the head of the Africa section… McDONALD: Well the head of the Africa program and the project on leadership and building state capacity at the Woodrow Wilson international center for scholars. 1 Q: That is easy for you to say. Thank you for getting that on the record, and it will be in the transcript. In the Wilson Center many would say the prime research center on the East Coast. McDONALD: I think it is true. It is a think tank a research and academic body that has approximately 150 fellows annually from all over the world looking at policy issues. -

We Were Cut Off from the Comprehension of Our Surroundings

Black Peril, White Fear – Representations of Violence and Race in South Africa’s English Press, 1976-2002, and Their Influence on Public Opinion Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln vorgelegt von Christine Ullmann Institut für Völkerkunde Universität zu Köln Köln, Mai 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work presented here is the result of years of research, writing, re-writing and editing. It was a long time in the making, and may not have been completed at all had it not been for the support of a great number of people, all of whom have my deep appreciation. In particular, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Bollig, Prof. Dr. Richard Janney, Dr. Melanie Moll, Professor Keyan Tomaselli, Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli, and Prof. Dr. Teun A. van Dijk for their help, encouragement, and constructive criticism. My special thanks to Dr Petr Skalník for his unflinching support and encouraging supervision, and to Mark Loftus for his proof-reading and help with all language issues. I am equally grateful to all who welcomed me to South Africa and dedicated their time, knowledge and effort to helping me. The warmth and support I received was incredible. Special thanks to the Burch family for their help settling in, and my dear friend in George for showing me the nature of determination. Finally, without the unstinting support of my two colleagues, Angelika Kitzmantel and Silke Olig, and the moral and financial backing of my family, I would surely have despaired. Thank you all for being there for me. We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. -

School Leadership Under Apartheid South Africa As Portrayed in the Apartheid Archive Projectand Interpreted Through Freirean Education

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION Kevin Bruce Deitle University of Montana, Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Deitle, Kevin Bruce, "SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECTAND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11696. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11696 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SCHOOL LEADERSHIP UNDER APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA AS PORTRAYED IN THE APARTHEID ARCHIVE PROJECT AND INTERPRETED THROUGH FREIREAN EDUCATION By KEVIN BRUCE DEITLE Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Educational Leadership The University of Montana Missoula, Montana March 2021 Approved by: Dr. Ashby Kinch, Dean of the Graduate School -

Fall 2011 • Volume Ix

FALL 2011 • VOLUME IX Fall 2011 • Volume IX EDITORS’ NOTE 4 OBAMA'S COUNTERTERRORISM POLICY STUART GOTTLIEB 5 THE CHina SYDNROME: THE EffecTS OF CHINESE INVESTmenT ON GoveRnance IN AFRIA MICHAEL CUSTER 11 THE CROSSRoaDS OF JUSTICE: WAR AND Peace IN LIBERIA DANIELLA MONTEMARANO 42 THE ImpacT OF UNION ON STATE DEBT AURELLE AMRAM 53 ValuaBLE Violence: THE ROLE OF REBellion IN SepaRATIST MovemenTS MICHELLE HOEFER 89 THE ImpacT OF Legal ORigin ON CONSTITUTional PRoviSIONS SARAH WALTON 108 Two SIDES OF THE COIN: HUMAN RIGHTS LevelS IN HOST AND INVESTOR COUNTRIES AS DETERminanTS OF FOReign DIRecT INVESTmenT CHERE SEE 133 This publication is published by New York University students. NYU is not responsible for its contents. 4 EDITORIAL BOARD EDITORS’ NOTE The articles in the Journal of Politics & International Affairs do not represent an agreement of beliefs and methodology. Readers are not expected to concur with all the opinions and research contained within these pages; the Journal seeks to inform and inspire the NYU community by presenting a wide variety of topics and opinions from a similarly broad range of ideologies and methods. Manuscripts submitted to the Journal of Politics & International Affairs are handled by an editorial board at New York University. Papers are submitted via e-mail and selected after several rounds of reading by the staff. Final selections are made by the editors-in-chief. Papers are edited for clarity, readability, and grammar in multiple rounds, during which at least three editors review each piece. Papers are assigned on the basis of fields of interest and expertise of the editors, in addition to a variety of other considerations such as equalization of the workload and the nature of the work necessary. -

Keep Nuclear Power out of the Cdm (Clean Development Mechanism)

KEEP NUCLEAR POWER OUT OF THE CDM (CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM) Nuclear Power Contradicts Clean Development: Too Little, Too Late, Too Expensive Too Dangerous The Following NGOs Have Joined the Call to Remove "Nuclear Activities" as an Option in the CDM as of 10 December 2008 Women in Europe for a Common Future International Forum on Globalization Greenpeace World Information Service on Energy (WISE) Ecodefense Russia Friends of the Earth International Nuclear Information and Resource Service (NIRS) 8th Day Center for Justice Illinois,USA ACDN (Action des Citoyens pour le Désarmement Nucléaire France AERO—Alternative Energy Resources Organization Montana, USA AGAT Kyrgyzstan Alianza por la Justicia Climatica Chile Alliance for Affordable Energy Louisiana,USA Alliance for Sustainable Communities-Lehigh Valley, Inc. Pennsylvania, USA ALMA-RO Association Romania Alternativa Verda ONG (Green Alternative) Spain/Catalunya Amigos da Terra - Amazônia Brasileira Brazil Amigos de la Tierra/FOE Spain Spain Amis de la Terre - Belgique Belgium Anti Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia Australia Anti Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia (ANAWA) Australia APROMAC - Environment Protection Association Brazil APROMAC - Environment Protection Association Brazil Arab Climate Alliance Lebanon Arizona Safe Energy Coalition Arizona, USA Artists for a Clean Future Asociación Contra Contaminación Ambiental de E.Echeverría Argentina Atomstopp Austria Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) Australia Banktrack Netherlands Bellefonte Efficiency and Sustainaibity -

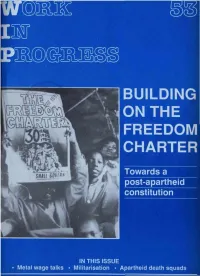

Building on The

wmm mmmsm BUILDING ON THE Towards a post-apartheid constitution IN THIS ISSUE Metal wage talks Militarisation • Apartheid death squads Editorial here is a sense in which government's closure of one newspaper, Tand threatened banning of a number of other publications, is justi fied. This is not because those publications are necessarily guilty of biased or inaccurate journalism, or even because they are in contravention of the over 100 statutes which limit what may be published. Rather, it is because any government which has as much to hide as South Africa's rulers must fear all but the most tame sections of the media. Nearly half of all the editions of Work In Progress produced over ten years were banned under the Publications Act. Yet not once was it suggested that inaccuracy or false information was the reason for banning. In warning Work In Progress that action against the magazine was being contemplated, Stoffel Botha claims to have looked at 24 articles contained in two editions of the magazine. Yet in not one case does he claim that information in an article was false. The conclusion is clear: publications like Work In Progress face closure or pre-publication censorship because of the accuracy of their reporting and analysis. • When an attorney-general declines to prosecute soldiers who kidnap, assault and threaten with death a political activist because the soldiers were acting in terms of emergency regulations; • when a head of state stops the trial of soldiers accused of murdering a Swapo member at a political meeting because