LJMU Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slang Terms and Code Words: a Reference for Law Enforcement

UNCLASSIFIED Slang Terms and Code Words: A Reference for Law DEA Enforcement Personnel Intelligence DEA-HOU-DIR-022-18 July 2018 ReportBrief 1 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED DEA Intelligence Report Executive Summary This Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Intelligence Report contains new and updated information on slang terms and code words from a variety of law enforcement and open sources, and serves as an updated version to the product entitled “Drug Slang Code Words” published by the DEA in May 2017. It is designed as a ready reference for law enforcement personnel who are confronted with hundreds of slang terms and code words used to identify a wide variety of controlled substances, designer drugs, synthetic compounds, measurements, locations, weapons, and other miscellaneous terms relevant to the drug trade. Although every effort was made to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information presented, due to the dynamics of the ever-changing drug scene, subsequent additions, deletions, and corrections are inevitable. Future addendums and updates to this report will attempt to capture changed terminology to the furthest extent possible. This compendium of slang terms and code words is alphabetically ordered, with new additions presented in italic text, and identifies drugs and drug categories in English and foreign language derivations. Drug Slang Terms and Code Wordsa Acetaminophen and Oxycodone Combination (Percocet®) 512s; Bananas; Blue; Blue Dynamite; Blueberries; Buttons; Ercs; Greenies; Hillbilly Heroin; Kickers; M-30s; -

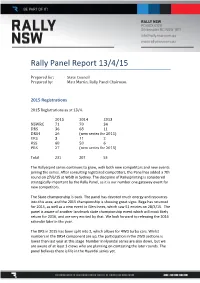

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 179 4 April 2011 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Contents Introduction 3 Standards cases In Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price) Channel 4, 7 December 2010, 22:00 5 [see page 37 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues)] Elite Days Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 12:00 to 13:15 Elite TV (Channel 965), 1 December 2010, 13:00 to 14:00 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 8 December 2010, 10.00 to 11:30 Elite Nights Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 22:30 to 23:35 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 6 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:25 Elite TV (Channel 965), 16 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:45 Elite TV (Channel 965), 22 December 2010, 00:50 to 01:20 Elite TV (Channel 965), 4 January 2011, 22:00 to 22:30 13 Page 3 Zing, 8 January 2011, 13:00 27 Deewar: Men of Power Star India Gold, 11 January 2011, 18:00 29 Bridezilla Wedding TV, 11 and 12 January 2011, 18:00 31 Resolved Dancing On Ice ITV1, 23 January 2011, 18:10 33 Not in Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues) Channel 4, 30 November 2010 to 29 December 2010, 22:00 37 [see page 5 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price)] Top Gear BBC2, 30 January 2011, 20:00 44 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Advertising Scheduling Cases In Breach Breach findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 47 Resolved Resolved findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 49 Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Mr Zac Goldsmith MP Channel 4 News, Channel 4, 15 and 16 July 2010 50 Other programmes not in breach 73 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Introduction The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes and licence conditions with which broadcasters regulated by Ofcom are required to comply. -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on The

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on the BBC’s Impartiality, Accountability and Integrity BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University International Anglophone Media Studies Laura Kaai 3617602 Simon Cook January 2013 7,771 Words 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Theoretical Framework 4 2.1 The BBC’s Values 4 2.1.2 Impartiality 5 2.1.3 Conflicts of Interest 5 2.1.4 Past Controversy: The Russell Brand Show and the Carol Thatcher Row 6 2.1.5 The Clarkson Controversy 7 2.2 Columns 10 2.3 Media Discourse Analysis 12 2.3.2 Agenda Setting, Decoding, Fairness and Fallacy 13 2.3.3 Bias and Defamation 14 2.3.4 Myth and Stereotype 14 2.3.5 Sensationalism 14 3. Methodology 15 3.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 15 3.1.2 Procedure 16 3.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 17 3.2.2 Procedure 19 4. Discussion 21 4.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 21 4.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 23 5. Conclusion 26 Works Cited 29 Appendices 35 3 1. Introduction “I’d have them all shot in front of their families” (“Jeremy Clarkson One”). This is part of the comment Jeremy Clarkson made on the 2011 public sector strikes in the UK, and the part that led to the BBC receiving 32,000 complaints. Clarkson said this during the 30 December 2011 live episode of The One Show, causing one of the biggest BBC controversies. The most widely watched factual TV programme in the world, with audiences in 212 territories worldwide, is BBC’s Top Gear (TopGear.com). -

Multi-Cultural. Dinner" Feast Prez: Search Firm Gauges'baruch

::- ~.--.-.;::::-:-u•._,. _._ ., ,... ~---:---__---,-- --,.--, ---------- - --, '- ... ' . ' ,. ........ .. , - . ,. -Barueh:-Graduate.. -.'. .:~. Alumni give career advice to Baruch Students.· Story· pg.17 VOL. 74, NUMBER 8 www.scsu.baruch.cuny.edu DECEM·HER 9, 1998 Multi-Cultural. Dinner" Feast Prez: Search Firm Gauges'Baruch. Opinion By Bryan Fleck Representatives from Isaacson Miller, a national search firm based in -Boston and San Francisco, has been hired by the Presidential Search Committee, chaired by Kathleen M. Pesile, to search for candidates for a permanent presi dent at Baruch College. The open forum on December 7 was held in order for the search firm to field questions and get the pulse of the Baruch community. Interim president Lois Cronholm is _not a candidate, as it is against CUNY regulations for an interim --------- president to become a full-time pres- ident. The search firm will gather the initial candidates, who will be . further screened by the Presidential " Search Committee, but the final choice lies with the CUNY Board of Trustees.' According to David Bellshow, an ......-.. ~.. Isaacson-Miller representative, the '"J'", average search takes approximately ; six months. Among the search firm's experience in the field of education ----~- - ..... -._......... *- -_. - -- -- _._- ...... -_40_. '_"__ - _~ - f __•••-. __..... _ •• ~. _• in NY are Columbia University and ... --- -. ~ . --. .. - -. -~ -.. New York University. In ~additi6n,, , New plan calls'for total re'structuririg the search fum also works with GovernDlents small and large foundations and cor ofStudent porations. By Bryan Fleck at large, would be selected from any The purpose ofthe open forum was In an attempt to strengthen undergraduate candidate. for the representatives of Isaacson . -

Fticrilty, Students. Ajld Commu~ Uniteagainstabolishing Open Atlm, Ibsionb

;.~':.. \ , ...... .' .... .. -- . ..... ~ r ..:. - ." ,. J l, -..... - . .. -: .'.. ' "_ ", •.•• 0.; •. ....., "" .. ,.. ..- .' .. ... _.~ "'...- - '-," .-. -•... -' ..'. ..... ,, ........ -, By Chan-joo.Moon ....... ;.. ' ..CollegePr-esident Matthew Goldste" will1 :v 'B' chCoP;"'':>""~~~' . ". ,lIt. .r-r-zr-» ea.e "aJ:U... : , to become. theeighthpresidentof.". Adelphi:University-ef'teCtive,JUna <~ 15. -The,. official announcement, ' _:: came·at'a·press conference on the"'f mornm-g'ofMareh2 at the CamPUS -,,~~. ofAdelphi,'UniverSity in Long Is- '; .: land. ' '" ,"Iwas l~~iingan_in~tifutionthat':·:. I .care deeply abOuti,an··institution,,~, ,that.Ihelped mold' withhigh stan- .: ~,, dards'and a. sense.of,community," .;:~~~ saidGoldstein. "[Butltherecomes: -: a time when your best work has. " already.been.demonstrated,": ' ,~~,~~nceme~~ cpmesatthe heelsof'the departure ofVice~i- ,·BaF~·.~.~G01~;-·-.~,:'~"tm~L:I8enberg, dentJamesMUithB on January 16~ et».draran~8oIirdof:'f'jzq~Ade"'hi:~t;y·"'" '"" ProVo$lbis'8:-etoo'fiholm:m-ayfin(:}-'" 'Stateeompt~tter'H~~al'tMeCaH;""fs~be~g,-ehaitinan 'of-Adelphi herselr.in_eh~:of-anthreetop and,Jtf~~~ Tetreault,·.viee -,: UIli~ity:~_ ~f trustees.. He postscfBaroChCollege: president, ,' presidentfor academic affairS at ' saidthatGoldstein· had demon vice president'and'provost. .- californi,aState-UniversityatFul-strateda"acholar1y statute, a com- The·tWo-~.~caDdid&testorthe ._ ..lertOn. -, ' ,'..:'.. '- ,'. ' Dlitm~Ju,J1!!iensiti~,J;Q~stll- prt!.Si~oJ\A~elphi:~~~~ee:' ·..~w Goldstein. w8$"the -'~"8nd'WoU1dtakeA4e1Phiin- -

Gigs of My Steaming-Hot Member of Loving His Music, Mention in Your Letter

CATFISH & THE BOTTLEMEN Van McCann: “i’ve written 14 MARCH14 2015 20 new songs” “i’m just about BJORK BACK FROM clinging on to THE BRINK the wreckage” ENTER SHIKARI “ukiP are tAKING Pete US BACKWARDs” LAURA Doherty MARLING THE VERDICT ON HER NEW ALBUM OUT OF REHAB, INTO THE FUTURE ►THE ONLY INTERVIEW CLIVE BARKER CLIVE + Palma Violets Jungle Florence + The Machine Joe Strummer The Jesus And Mary Chain “It takes a man with real heart make to beauty out of the stuff that makes us weep” BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME15011142.pgs 09.03.2015 11:27 EmagineTablet Page HAMILTON POOL Home to spring-fed pools and lush green spaces, the Live Music Capital of the World® can give your next performance a truly spectacular setting. Book now at ba.com or through the British Airways app. The British Airways app is free to download for iPhone, Android and Windows phones. Live. Music. AustinTexas.org BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME15010146.pgs 27.02.2015 14:37 BAND LIST NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 14 MARCH 2015 Action Bronson 6 Kid Kapichi 25 Alabama Shakes 13 Laura Marling 42 The Amorphous Left & Right 23 REGULARS Androgynous 43 The Libertines 12 FEATURES Antony And The Lieutenant 44 Johnsons 12 Lightning Bolt 44 4 SOUNDING OFF Arcade Fire 13 Loaded 24 Bad Guys 23 Lonelady 45 6 ON REPEAT 26 Peter Doherty Bully 23 M83 6 Barli 23 The Maccabees 52 19 ANATOMY From his Thai rehab centre, Bilo talks Baxter Dury 15 Maid Of Ace 24 to Libs biographer Anthony Thornton Beach Baby 23 Major Lazer 6 OF AN ALBUM about Amy Winehouse, sobriety and Björk 36 Modest Mouse 45 Elastica -

Bloomsbury MUSIC Cat.Indd

MUSIC & SOUND STUDIES 2013-14 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS 33 1/3 is a series of short books about popular music, focusing on individual albums by a variety of artists. Launched in 2003, the series will publish its 100th book in 2014 and has been widely acclaimed and loved by fans, musicians and scholars alike. LAUNCHING SPRING 2014 new in 2013 new in 2013 new in 2014 9781623562878 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623569150 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623567149 $14.95 | £8.99 new in 2014 new in 2014 new in 2014 Bloomsbury Collections delivers instant access to quality research and provides libraries with a exible way to build ebook collections. 9781623568900 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623560652 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623562588 $14.95 | £8.99 Including ,+ titles in subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, the platform features content from Bloomsbury’s latest research publications as well as a + year legacy including Continuum, Berg, Bristol Classical Press, T&T Clark and The Arden Shakespeare. ■ Music & Sound Studies collection ■ Search full text of titles; browse available in , including ebooks by speci c subject new in 2014 new in 2014 new in 2014 from the Continuum archive ■ Download and print chapter PDFs ■ Instant access to s of key works, without DRM restriction easily navigable by research topic ■ Cite, share and personalize content RECOMMEND TO YOUR LIBRARY & SIGN UP FOR NEWS ▶ 9781623561222 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623561833 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623564230 $14.95 | £8.99 REGISTER FOR LIBRARY TRIALS AND QUOTES ▶ bloomsbury.com • 333sound.com • @333books [email protected] www.bloomsburycollections.com BC ad A5 (music).indd 1 08/10/2013 14:19 CONTENTS eBooks Contents eBook availability is indicated under each book entry: Individual eBook: available for your e-reader. -

The Outcast Dead, by Paul Slade

The Outcast Dead, by Paul Slade. © Paul Slade 2013, all rights reserved. This book first appeared on http://www.PlanetSlade.com. The Outcast Dead by Paul Slade Contents Introduction 2 Chapter 1: The Romans 4 Chapter 2: Arriving at the vigil 7 Chapter 3: Laying siege 10 Chapter 4: Samhain at the gates 12 Chapter 5: Birth of the Liberty 15 Chapter 6: Emily’s plaque 23 Chapter 7: The Black Death 27 Chapter 8: The Invisible Gardener 34 Chapter 9: Farewell to the stews 38 Chapter 10: The Southwark Mysteries 43 Chapter 11: Bardic Bankside 45 Chapter 12: Going underground 51 Chapter 13: Puritans and plagues 56 Chapter 14: Crossbones Girl 61 Chapter 15: The stink industries 64 Chapter 16: Say my name 66 Chapter 17: Resurrection men 69 Chapter 18: John Crow’s megaphone 75 Chapter 19: Seeking closure 78 Chapter 20: What happens next? 89 Appendices 92 Sources & footnotes 117 © Paul Slade, 2013, all rights reserved. This book first appeared on www.PlanetSlade.com. 1 The Outcast Dead, by Paul Slade. © Paul Slade 2013, all rights reserved. This book first appeared on http://www.PlanetSlade.com. Introduction “I have heard ancient men of good credit report that these single women were forbidden the rites of the church so long as they continued their sinful life and were excluded from Christian burial. And therefore, there was a plot of ground, called the single woman’s churchyard, appointed for them far from the parish church.” - John Stow’s Survey of London, 1598. “Sleep well, you winged spirits of intimate joy.” - Note taped to Cross Bone’s fence, 2011. -

LUSH – Blind Spot EP

LUSH – Blind Spot EP thevpme.com /2016/02/29/lush-blind-spot-ep/ By Andy Von 2/29/2016 Pip We’ve missed quite a lot since we’ve been away, including the return of Lush !! Unlike many recent reformations which trade entirely on nostalgia, Lush’s return has been marked by the release of their first music in twenty years in the shape of a brand new EP. There also appears to be a suggestion that more material may be forthcoming at a future date. The Blind Spot EP which is released on the 15th April on the band’s own Edamame label sees Miki Berenyi, Emma Anderson, Phil King reunited along with Justin Welch (formerly Elastica, stepping in for the late Chris Acland) and it sounds like they’ve never been away. The production from Jim Abbiss and Ladytron’s Daniel Hunt is perfectly judged retaining that classic Lush sound, and whilst it reaches back to touch fingers with the past, it very definitely moves the band into the here and now. Lush sound more like their beginnings than their endings on Blind Spot, but it’s also the sound of a band not straining to reclaim former glories. There comes a time in life when you realise that perhaps spray on skinny jeans is a look best left in the past and instead of clinging desperately to the memory of your faded youth, you embrace the person you are today. Blind Spot is an elegant, sophisticated example of where Lush are now and it manages to seamlessly bridge their twenty-year absence with an uncomplicated sense of dignity and grace.