The Development of Secularism in Turkey This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Developm.Ent of Secularism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About the Artistic and Performing Features of Violin Works Gara Garayev About the Artistic and Performing Features of Violin Works of Gara Garayev

CEYLA GANİOĞLU CEYLA ABOUT THE ARTISTIC AND PERFORMING FEATURES OF VIOLIN WORKS OF GARA GARAYEV OF VIOLIN WORKS GARA AND PERFORMING FEATURES ARTISTIC THE ABOUT ABOUT THE ARTISTIC AND PERFORMING FEATURES OF VIOLIN WORKS OF GARA GARAYEV Art Proficiency Thesis by CEYLA GANİOĞLU Department of Bilkent University 2019 Music İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara May 2019 ABOUT THE ARTISTIC AND PERFORMING FEATURES OF VIOLIN WORKS OF GARA GARAYEV The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by CEYLA GANİOĞLU In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of ART PROFICIENCY IN MUSIC THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA May 2019 ABSTRACT ABOUT THE ARTISTIC AND PERFORMING FEATURES OF VIOLIN WORKS OF GARA GARAYEV Ganioğlu, Ceyla Proficiency in Music, Department of Music Supervisor: Prof. Gürer Aykal May 2019 Garayev’s unique talents of music opened a new page in Azerbaijan’s music of 20th century. He adapted an untypical way of making music in which he was able to combine the traditional and the modern type. There are several substances that were brought in music of Azerbaijan by Garayev such as new themes, new images, and new means of composing. He achieved success not only in the areas of the national ballet, choral, and chamber music but also panned out well considering sonata for violin and piano and the violin concerto. These works represents main aspects and characteristics of Garayev’s music like implementation of national traditions while applying new methods of the 20th century, specifically neo-classicism and serial technique. In both sonata for violin and piano and the violin concerto, he reflects a perspective of synthesis of the two musical systems that are the Eastern and the Western. -

The South Caucasus 2018

THE SOUTH CAUCASUS 2018 FACTS, TRENDS, FUTURE SCENARIOS Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) is a political foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany. Democracy, peace and justice are the basic principles underlying the activities of KAS at home as well as abroad. The Foundation’s Regional Program South Caucasus conducts projects aiming at: Strengthening democratization processes, Promoting political participation of the people, Supporting social justice and sustainable economic development, Promoting peaceful conflict resolution, Supporting the region’s rapprochement with European structures. All rights reserved. Printed in Georgia. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Regional Program South Caucasus Akhvlediani Aghmarti 9a 0103 Tbilisi, Georgia www.kas.de/kaukasus Disclaimer The papers in this volume reflect the personal opinions of the authors and not those of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation or any other organizations, including the organizations with which the authors are affiliated. ISBN 978-9941-0-5882-0 © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V 2013 Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................ 4 CHAPTER I POLITICAL TRANSFORMATION: SHADOWS OF THE PAST, FACTS AND ANTICIPATIONS The Political Dimension: Armenian Perspective By Richard Giragosian .................................................................................................. 9 The Influence Level of External Factors on the Political Transformations in Azerbaijan since Independence By Rovshan Ibrahimov -

Baku, the Philharmonic and Shostakovich

D O C U M E N T A R Y I I I Baku, The Philharmonic and Shostakovich Aida Huseynova On January 27, 2004 a quite special event took place in Baku, A z e r b a i j a n ’s capital: the Azerbaijan State Philharmonic Hall opened after seven years of complete renovation. A splendid ceremony was held in the presence of Ilham A l i y e v, President of the Azerbaijan Republic and other dignitaries. A z e r b a i j a n ’s State Symphonic Orchestra conducted by Rauf Abdullayev also performed works by local composers - big names of the twentieth century in fact - namely which Azerbaijan passed during the common words heard at school at the Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Kara Karaev and past century: N i k o l a y e v s k a y a ( i n end of each day. Baku Philharmonic Fikrat A m i r o v. honour of the last Russian Ts a r, Nicolas had a reputation as one of the best II), Kommunisticheskaya (each city or concert halls in the Soviet Union. The Then came a solo performance by even a small village in the Soviet Union beauty of its architectural design and Mstislav (‘Slava’) Rostropovich of had a street named corresponding to the i n t e r i o r, the perfect acoustics, the B a c h ’s S a r a b a n d e from the Suite No. ruling party) and now I s t i g l a l i y y a t intellect and Eastern warmth of the 3 followed by the premiere of a piece (‘Independence’, in Azerbaijani). -

Science Versus Religion: the Influence of European Materialism on Turkish Thought, 1860-1960

Science versus Religion: The Influence of European Materialism on Turkish Thought, 1860-1960 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Serdar Poyraz, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Carter V. Findley, Advisor Jane Hathaway Alan Beyerchen Copyright By Serdar Poyraz 2010 i Abstract My dissertation, entitled “Science versus Religion: The Influence of European Materialism on Turkish Thought, 1860-1960,” is a radical re-evaluation of the history of secularization in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. I argue that European vulgar materialist ideas put forward by nineteenth-century intellectuals and scientists such as Ludwig Büchner (1824-1899), Karl Vogt (1817-1895) and Jacob Moleschott (1822-1893) affected how Ottoman and Turkish intellectuals thought about religion and society, ultimately paving the way for the radical reforms of Kemal Atatürk and the strict secularism of the early Turkish Republic in the 1930s. In my dissertation, I challenge traditional scholarly accounts of Turkish modernization, notably those of Bernard Lewis and Niyazi Berkes, which portray the process as a Manichean struggle between modernity and tradition resulting in a linear process of secularization. On the basis of extensive research in modern Turkish, Ottoman Turkish and Persian sources, I demonstrate that the ideas of such leading westernizing and secularizing thinkers as Münif Pasha (1830-1910), Beşir Fuad (1852-1887) and Baha Tevfik (1884-1914) who were inspired by European materialism provoked spirited religious, philosophical and literary responses from such conservative anti-materialist thinkers as Şehbenderzade ii Ahmed Hilmi (1865-1914), Said Nursi (1873-1960) and Ahmed Hamdi Tanpınar (1901- 1962). -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

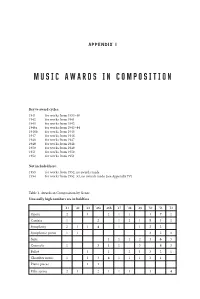

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

RESPONSES to INFORMATION REQUESTS (Rirs) Page 1 of 3

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 16 January 2007 GEO102248.E Georgia: Reports of violence against Azerbaijanis; response of government authorities (2005 - 2006) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa According to Georgia's 2002 census, there are approximately 285,000 ethnic Azerbaijanis in the country, comprising 6.5 percent of the total population (ICG 22 Nov. 2006, 1; ECMI Oct. 2006, 54). Several media reports explain that the most important issues facing Georgia's Azerbaijani population involve socio-political integration (ibid., 55; ICG 22 Nov. 2006, i; Interfax News Agency 27 June 2005) and land privatization (ECMI Oct. 2006, 55; Turan Information Agency 19 Sept. 2006; FIDH Oct. 2006, Sec. D), which many Azerbaijanis believe favours ethnic Georgians (ICG 22 Nov. 2006, 5). In February 2006, Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili toured Azerbaijani areas of Georgia to ascertain their living conditions and record complaints from villagers (Assa-Irada News Agency 16 Feb. 2006). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) reports that in December 2004, in the Marneuli district, a security guard fired on a group of Azerbaijani villagers, some of whom were armed, who were protesting a land allocation scheme (RFE/RL 7 Dec. 2004). One elderly Azerbaijani woman was killed and several other protesters were injured in the shooting (ibid.; ANS TV 13 Dec. 2004; ICG 22 Nov. 2006, 5). According to Baku-based ANS TV, the Georgian prosecutor's office was investigating the death of the woman and on 13 December 2004, announced that the culprit would be "arrested soon" (13 Dec. -

Three Turkish Composers and Their Paris Education Years

Universal Journal of Educational Research 6(11): 2577-2585, 2018 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2018.061123 Three Turkish Composers and Their Paris Education Years Sirin Akbulut Demirci Department of Music Education, Faculty of Education, Bursa Uludag University, Turkey Copyright©2018 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The first Turkish musicians who chose and Necil Kazım Akses (1908-1999) were born during the composing as a profession were called “The Turkish Five”. early 1900s. After Ottoman Empire, the new Republic of These composers, listed by their date of birth, were: Cemal Turkey was founded, and a new strategy was established Reşit Rey, Hasan Ferit Alnar, Ulvi Cemal Erkin, Ahmet for musical policies. Based on this policy, the intention was Adnan Saygun and Necil Kazım Akses. These composers to mix monophonically structured Turkish music with squeezed the 500 year music culture of Western music into Western tonality and to create a new type of Turkish music 30-40 years and made important contributions to Turkish with this Western-polyphonic perspective [2]. contemporary music. The Turkish five went abroad for The “Turkish Five” were born during the early 1900s. education and brought their educational and musical They were the first Turkish musicians who were sent culture heritage back to Turkey. Of Turkish Five, Cemal abroad by the government, although there were Ottoman Reşit Rey, Ulvi Cemal Erkin and Ahmet Adnan Saygun students sent to France for art education in the Tanzimat studied in France. -

The Environment and Early Influences Shaping Political Thought of Niyazi Berkes in British Cyprus, 1908-1922*

The Environment and Early Influences Shaping Political Thought of Niyazi Berkes in British Cyprus, 1908-1922* Şakir Dinçşahin Yeditepe University Abstract Niyazi Berkes was born on 21 September 1908 in Nicosia/Lefkoşa, the capital of Cyprus. Naturally, his intellectual personality began to be shaped by the social and political context on the island as well as the empire which was in the process of imperial change. As a result of the turmoil created by the British rule, the Young Turk Revolution, the First World War, and the Turkish national struggle, the Greek and the Turkish identities for the Orthodox and the Muslim communities, respectively, were constructed. Niyazi Berkes, who was born and raised in this turbulent period, developed the Turkish national identity that laid the foundations of his patriotism among the Muslim community. But in the early years of his long life, the social and political context of Cyprus also planted the seeds of his liberal-mindedness. Key Words: Niyazi Berkes, Nationalism, National Identity, British Rule, Young Turks, World War I, Turkish National Struggle. Özet Niyazi Berkes 21 Eylül 1908’de İngiliz idaresine devredilmiş olan Doğu Akdeniz’deki Osmanlı adası Kıbrıs’ın Lefkoşa şehrinde dünyaya gelmiştir. Niyazi Berkes’in çocukluk ve yetişme döneminde entelektüel kişiliğini belirgin bir biçimde etkilemiş olan üç temel olgudan bahsedilebilir. Bunlardan birincisi Kıbrıs’taki özgür düşünce ortamı, ikincisi Kıbrıs’taki Müslüman ve Ortodoks cemaatlerin uluslaşma sürecine girmeleriyle beraber ortaya çıkan etnik gerilimdir. Sonuncusu ise Birinci Dünya Savaşı (1914– 1918) ile Anadolu’daki bağımsızlık mücadelesinin Kıbrıs’taki Müslüman- Türk ahali üzerinde yarattığı travmadır. Bu olgulardan Kıbrıs’taki liberal düşünce ortamı, Niyazi Berkes’in özgürlükçü bir aydın olmasının temellerini atmıştır. -

2021 Finalist Directory

2021 Finalist Directory April 29, 2021 ANIMAL SCIENCES ANIM001 Shrimply Clean: Effects of Mussels and Prawn on Water Quality https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51706 Trinity Skaggs, 11th; Wildwood High School, Wildwood, FL ANIM003 Investigation on High Twinning Rates in Cattle Using Sanger Sequencing https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51833 Lilly Figueroa, 10th; Mancos High School, Mancos, CO ANIM004 Utilization of Mechanically Simulated Kangaroo Care as a Novel Homeostatic Method to Treat Mice Carrying a Remutation of the Ppp1r13l Gene as a Model for Humans with Cardiomyopathy https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51789 Nathan Foo, 12th; West Shore Junior/Senior High School, Melbourne, FL ANIM005T Behavior Study and Development of Artificial Nest for Nurturing Assassin Bugs (Sycanus indagator Stal.) Beneficial in Biological Pest Control https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51803 Nonthaporn Srikha, 10th; Natthida Benjapiyaporn, 11th; Pattarapoom Tubtim, 12th; The Demonstration School of Khon Kaen University (Modindaeng), Muang Khonkaen, Khonkaen, Thailand ANIM006 The Survival of the Fairy: An In-Depth Survey into the Behavior and Life Cycle of the Sand Fairy Cicada, Year 3 https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51630 Antonio Rajaratnam, 12th; Redeemer Baptist School, North Parramatta, NSW, Australia ANIM007 Novel Geotaxic Data Show Botanical Therapeutics Slow Parkinson’s Disease in A53T and ParkinKO Models https://projectboard.world/isef/project/51887 Kristi Biswas, 10th; Paxon School for Advanced Studies, Jacksonville, -

Azerbaijan's Journey Through Jazz

Art 40 www.irs-az.com 43, SPRING 2020 Ian PEART Saadat IBRAHIMOVA Azerbaijan’s journey through jazz - Another Sarabski Milestone - www.irs-az.com 41 Art Outstanding Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov istory, geography and character have Azerbaijani was finally persuaded to take on the role of Leyli. As for people ideally placed to enrich their own cul- Majnun, the role proved to be the springboard for the Hture with the best of the many others that pass long and distinguished career of Huseyngulu Sarabski. this way. Cultural exchange was a feature of the ancient An operatic tenor, Sarabski was equally proficient at Silk Road and is likely to continue as the current Belt and singing mugham and in 1926 was a soloist with the Road Initiative progresses. This has been no one-way Eastern Orchestra entrancing Moscow audiences with process; spot the carpets from this region that found traditional songs and music1. Remember that family their way into Renaissance paintings. And over the last name, its reappearance 83 years later forms the second hundred years or so, Azerbaijan has made remarkable part of this story. contributions to cross-cultural exchanges of music. As if Uzeyir bey did not do enough in introducing Musical pioneer opera, promoting local culture and women’s eman- On 12 January 1908, an opera was staged in a Baku cipation among other more liberal social values in his theatre. Composed by the 22-year-old Uzeyir Hajibeyov, theatrical works, he was also instrumental in the found- it was the first opera in the Muslim East; the first to fea- ing of the Azerbaijan State Conservatoire in 1920 (since ture traditional Azerbaijani folk instruments alongside 1991 the Baku Academy of Music). -

Statesmen and Public-Political Figures

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CONTENTS STATESMEN, PUBLIC AND POLITICAL FIGURES ........................................................... 4 ALIYEV HEYDAR ..................................................................................................................... 4 ALIYEV ILHAM ........................................................................................................................ 6 MEHRIBAN ALIYEVA ............................................................................................................. 8 ALIYEV AZIZ ............................................................................................................................ 9 AKHUNDOV VALI ................................................................................................................. 10 ELCHIBEY ABULFAZ ............................................................................................................ 11 HUSEINGULU KHAN KADJAR ............................................................................................ 12 IBRAHIM-KHALIL KHAN ..................................................................................................... 13 KHOYSKI FATALI KHAN ..................................................................................................... 14 KHIABANI MOHAMMAD ..................................................................................................... 15 MEHDİYEV RAMİZ ............................................................................................................... -

The Making of Modern Turkey

The making of modern Turkey Turkey had the distinction of being the first modern, secular state in a predominantly Islamic Middle East. In this major new study, Feroz Ahmad traces the work of generations of reformers, contrasting the institution builders of the nineteenth century with their successors, the ‘Young Turks’, engineers of a new social order. Written at a time when the Turkish military has been playing a prominent political role, The Making of Modern Turkey challenges the conventional wisdom of a monolithic and unchanging army. After a chapter on the Ottoman legacy, the book covers the period since the revolution of 1908, examining the processes by which the new Turkey was formed. Successive chapters then chart progress through the single-party regime set up by Atatürk, the multi-party period (1945– 60) and the three military interventions of 1960, 1971 and 1980. In conclusion, the author examines the choices facing Turkey’s leaders today. In contrast to most recent writing, throughout his analysis, the author emphasises socio-economic changes rather than continuities as the motor of Turkish politics. Feroz Ahmad is a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts at Boston. He is the author of The Young Turks (1969) and The Turkish Experiment in Democracy 1950–75 (1977). The Making of the Middle East Series State, Power and Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East Roger Owen The making of modern Turkey Feroz Ahmad London and New York First published 1993 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Transferred to Digital Printing 2002 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003.