The Feasibility for Providing a More Sustainable Menu for Hong Kong's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix V Letter from the Market Consultant in Relation to Its Hong Kong Hotel Industry Report

APPENDIX V LETTER FROM THE MARKET CONSULTANT IN RELATION TO ITS HONG KONG HOTEL INDUSTRY REPORT RevPAR of RKH and High Tariff A Hotels, 1997 to 2005 High Tariff A Regal Kowloon Hotel Kowloon Shangri-La HK$ 1,600 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Source: HKTB, Regal Hotels International Ltd., Shangri-La Asia Limited, Savills Research & Consultancy The movement of the RevPAR of RKH has generally tracked the High Tariff A hotel average. RevPAR was affected by the Asian Financial Crises (1997-8) and SARS (2003) but reacted to favorable market conditions such as the I.T. boom (2000), the post SARS recovery and the implementation of IVS (2003). Despite the volatility, the average annual growth rate of the RevPAR of RKH between 1997 and 2005 was 1% per annum, lower than the High Tariff A hotel average of 4% per annum, largely reflecting the negative impact of its aging facilities. It is noteworthy that in 2005, since occupancy rates were at high levels, operators have been more aggressive in raising room rates and RKH was no exception. RevPAR in 2005 was therefore driven largely by room rate rises. The average room rate of RKH over 2006 recorded a strong increase of 16% compared with the same period in 2005. The average occupancy rate also increased to 86%, compared with 84% recorded over the same period last year, RevPAR over this period increased by approximately 18%. Outlook RKH is strategically located in a traditional tourist node and a core business district. -

Tour Hong Kong Ocean Park

Tour Hong Kong Ocean Park Khách sạn có đưa đón trong khu vực Hong Kong Best Western Hotel Causeway Bay Butterfly on Victoria City Garden Conrad Hong Kong Cosmo Cosmopolitan Courtyard By Marriott Crowne Plaza Hong Kong Causeway Bay Dorsett Regency Hong Kong (chỉ áp dụng khu khách sạn) East Hotel (chỉ áp dụng khu khách sạn) Empire Hotel, Causeway Bay Empire Hotel, Wanchai Fenwick Pier Four Seasons Hotel Hong Kong Gloucester Luk Kwok Hotel Grand Hyatt Hong Kong Harbour Grand Hong Kong Harbour Plaza North Point Holiday Inn Express Causeway Bay HK Hotel Bonaparte By Rhombus Island Pacific Island ShangriLa JW Marriott Hotel Hong Kong L'Hotel Causeway Bay Harbour View Metropark Hotel, Causeway Bay Metropark Hotel, Wanchai Newton Hotel Hong Kong Newton Inn North Point Novotel Century Hong Kong Park Lane Hong Kong Ramada Hong Kong Regal Hong Kong Renaissance Harbour View Rosedale on the Park Shun Tak Centre Room #307 South China Hotel South Pacific Hotel Traders Hotel The Charterhouse Causeway Bay The Excelsior Hong Kong The Harbour View The Wharney Guang Dong Hong Kong Khách sạn có đưa đón trong khu vực Kowloon B P International House Booth Lodge (The Salvation Army) Butterfly on Prat Caritas Bianchi Lodge Dorsett Mong Kok Hotel Eaton Smart Hotel Goodrich Hotel Guangdong Hotel Hong Kong Harbour Grand Kowloon Harbour Plaza 8 Degrees Harbour Plaza Metropolis Holiday Inn Golden Mile Hotel Icon Hotel Panorama by Rhombus Hung Hom MTR Station #K1 Hyatt Regency Hong Kong TST InterContinental -

Corporate Profile 集團概要

Corporate Profile 集團概要 The Great Eagle Group is one of Hong Kong’s leading property and hotel companies, with an experienced management team known for its track record in evaluating and capitalising on cycles in property markets. Headquartered in Hong Kong, the Group develops, invests in and manages high quality office, retail, residential and hotel properties in Hong Kong, North America and Europe. Its core commercial properties comprise 1.59 million square feet of Grade-A office space in the prime commercial districts of Hong Kong. It is also developing a 1.76 million square feet office, retail and hotel complex in the prime shopping district of Mongkok, Kowloon. In the United States, it owns or has investment interests in four office buildings with a total floor area of 784,000 square feet. The Group’s extensive hotel portfolio currently comprises seven properties with over 4,000 rooms, including two Great Eagle branded (re-branded as Langham Hotels International in February 2003) and managed hotels in Hong Kong and five luxury hotels in London, Toronto, Boston, Melbourne and Auckland managed by a variety of leading hotel names. An experienced asset management team from Great Eagle oversees the portfolio to enhance performance. The Group is also active in property management and maintenance services as well as building materials trading. The Group was founded in 1963 in the form of The Great Eagle Company, Limited, which listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 1972. In 1990, Great Eagle Holdings Limited, a company incorporated in Bermuda, became the listed company and holding company of the Group. -

CME Cat. a Activities 2011Hot!

12/13/12 CME Category A Activities ‑ 2011 Past CME Category A Activities 2011 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec January 2011 03 Jan 2011 Topic: A) Image guided radiotherapy (IGRT) with breathing control in lung cancer B) Management of Adverse GI Event during AntiPlatelet Therapy Venue: The Chapel, 9/F, Block D, Hong Kong Baptist Hospital Time: 20:00-22:00 Speaker: A) Dr Chiu Kwok Wing B) Ng Fook Hong Organizer: Hong Kong Baptist Hospital Cat A 1 pt (for topic B only) Coordinator: Ms Kandy Wan Enquiry: Tel 2963 5521 04 Jan 2011 Topic: Practical Paediatric Cardiology Course 18 Jan 2011 01 Feb 2011 Venue: Seminar Room, HA Bldg 15 Feb 2011 Time: 18:00-20:00 Speaker: Various Organizer: Hong Kong Society of Paediatrics Cardiology Cat A 2 pts Coordinator: Ms Dora Wong Enquiry: Tel 2958 6656 06 Jan 2011 Topic: 催眠治療臨床應用課程基礎訓練)(Every Thursday) 13 Jan 2011 20 Jan 2011 Venue: Lecture Hall, 4/F, Duke of Windsor Social Service Building, 15 27 Jan 2011 Hennessy Road, Wanchai localhost/Users/gareth/Dropbox/College/web/home/paediatr/www/…/cme 2011 a.htm 1/222 12/13/12 CME Category A Activities ‑ 2011 Time: 19:00 - 21:30 Speaker: 尹婉萍小姐 Organizer: The Federation of Medical Societies of Hong Kong / The Cat A 3 pts Centre on Health & Wellness / The Hong Kong Society for Rehabilitation Coordinator: Ms Erica Hung Enquiry: Tel 2527 8898 [email protected] 06 Jan 2011 Topic: Certificate Course on Management of Drug Abuse Patients 13 Jan 2011 for Family Doctors 20 Jan 2011 27 Jan 2011 Venue: Auditorium, Pok Oi Hospital 20 Feb 2011 27 Feb 2011 Time: 13:00 -

Membership List

MEMBERSHIP LIST Hotel Address Tel.No. Fax.No. 99 Bonham 99 Bonham Strand, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong 3940 1111 3940 1100 Auberge Discovery Bay Hong Kong 88 Siena Avenue Discovery Bay Lantau Island, Hong Kong 2295 8288 2295 8188 BEST WESTERN Grand Hotel 23 Austin Avenue, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon 3122 6222 2730 9328 BEST WESTERN Hotel Causeway Bay Cheung Woo Lane, Canal Road West, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2496 6666 2836 6162 BEST WESTERN Hotel Harbour View 239 Queen’s Road West, Hong Kong 2599 9888 2559 1266 BEST WESTERN PLUS Hotel Hong Kong 308 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 3410 3333 2559 8499 Best Western PLUS Hotel Kowloon 73-75 Chatham Road South, Tsimshatsui, Kowloon 2311 1100 2311 6000 Bishop Lei International House 4 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong 2868 0828 2868 1551 Butterfly on Morrison 39 Morrison Hill Road, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 3962 8333 3962 8322 Butterfly on Prat 21-23A Prat Avenue, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon 3962 8888 3962 8889 The Charterhouse Causeway Bay 209-219 Wanchai Road, Hong Kong 2833 5566 2833 5888 City Garden Hotel 9 City Garden Road, North Point, Hong Kong 2887 2888 2887 1111 The Cityview 23 Waterloo Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon 2783 3888 2783 3899 Conrad Hong Kong Pacific Place, 88 Queensway, Hong Kong 2521 3838 2521 3888 Cordis Hong Kong 555 Shanghai Street, Mongkok, Kowloon 3552 3388 3552 3322 Cosmo Hotel Hong Kong 375-377 Queen’s Road East, Wanchai, Hong Kong 3552 8388 3552 8399 Courtyard by Marriott Hong Kong 167 Connaught Road West, Hong Kong 3717 8888 3717 8228 Courtyard by Marriott Hong Kong Sha Tin 1 On Ping -

Company Profile 2021

COMPANY PROFILE 2021 BAP TECHNOLOGY CONSULTANTS LTD SOLUTION HOUSE @ LIGHTING ˙CONTROL ˙ PRO AV www.bap.com.hk INDEX 1 About Us 1.1 Mission ........................................................................................................ 2 1.2 Functional Chart ......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Recognized Qualifications & Membership ................................................. 4 1.4 Professional Qualification for our Staff ...................................................... 4 2 Our Services 2.1 Audiovisual System ..................................................................................... 6 2.2 Acoustic Sound Systems ............................................................................. 7 2.3 Stage / Specialty Lighting System ............................................................... 8 3 Portfolio 3.1 Hotel / Casino / Club House ........................................................................ 9 3.2 Restaurant ................................................................................................ 10 3.3 Retail ......................................................................................................... 11 3.4 Bank / Financial Institution ...................................................................... 12 3.5 Public Institution ....................................................................................... 13 3.6 Education ................................................................................................. -

May 6, 2020 TO: ASMI Board of Directors FROM: Hannah Lindoff, Senior Director of Global Marketing & Strategy RE: International Program Report

DATE: May 6, 2020 TO: ASMI Board of Directors FROM: Hannah Lindoff, Senior Director of Global Marketing & Strategy RE: International Program Report The international program received a Market Access Program (MAP) funding award of $4,453,652 for FY21. The FY 2021 international program spend plan also includes $1,540,000 in Agricultural Trade Promotion Program (ATP) funds and $2,495,000 in matching funds, for a total budget of $8,488,652 to conduct marketing programs in nine regional programs across the globe. Included in this budget are ATP funds specifically set aside to fund activities managed by the technical program, communications program, and sustainability program. This budget reflects the broad diversification strategy that ASMI international embarked upon with the advent of ATP funding in 2019. The budget also reflects a five year spend plan for ATP. Although official confirmation is pending, we have received un-official confirmation that our proposal to extend ATP across five years rather than three has been approved. With the outbreak of a novel coronavirus first detected in China in December 2019, the ASMI international program began to deal with the effects of COVID-19 at the beginning of 2020. Shipments to China had already slowed substantially due to the ongoing tariff situation, but the extension of the Lunar New Year and extended shutdowns in processing facilities and ports sent ripple effects throughout the global supply chain and as early as late January, ASMI saw its first cancelled events. In February, ASMI welcomed the first ever millennial in-bound mission to Alaska, bringing buyers from the “next generation” to Seattle and Kodiak. -

Play Is the Thing

Friday, August 31, 2018 13 Creative heads Play is the thing KW: We put on Alice in Stuckyland in the Central Harbourfront Event Space immersive theater projects. Eventually we would like to produce Editor’s Note: Onnie Chan and King Wong run Banana E ect — a as well as in Nursery Park, West Kowloon Cultural District. The world the other three as well. Hong Kong-based theater company that believes in putting the audi- we created was fi ctional (a take on Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in We thought we’d do a sci-fi version of Journey to the West, set in the ence at the center of their activities. e duo spoke to China Daily Wonderland). It was manic, crazy and chaotic in some ways. future. I bet no one has tried something like this before! Hong Kong about their forthcoming production, a futuristic participa- The idea was to let the audience have a taste of di erent possible expres- tory theater piece based on the Chinese classic, Journey to the West. sions of immersive theater. They got some physical exercise by walking Q: Is it very hi-tech? through a maze we created. Instructions were radioed to them through OC: Not terribly hi-tech, but there will be some use of smartphone tech- earphones. It was as if the Cheshire Cat from Alice was playing a game of nology. We did a bit of investigation trying to gauge how people Onnie Chan (OC) King Wong (KW) hide-and-seek with them. Interestingly, when participants walked out of would like the future to look. -

Emerging Cross Border Tourism Region Macau-Zhuhai: Place in Play/Place to Play

Emerging Cross Border Tourism Region Macau-Zhuhai: Place in Play/Place to Play Hendrik Tieben School of Architecture, Thes Chinese University of Hong Kong Wong Foo Yuan Bld. 610G, CUHK Campus, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong SAR Email: [email protected] Abstract: n This paper explores the new tourism region Macau-Zhuhai which is emerging in the south-western part of the Pearl River Delta (PRD). Since Macau’s handover to the People’s Republic of China in 1999, the former Portuguese enclave is becoming increasingly integrated into the PRD. Together with its mainland neighbor Zhuhai it is creating a bi-city region; although without coordinated planning. Currently, both cities embark on a first joint project encouraged by the Chinese Central Government on the island Hengqin. The paper is investigating the attempts of both cities to re- invent themselves as places to play and how they find themselves on the playing field of global and national forces. The paper ends with the suggestion of an alternative understanding of tourism and destinations which learns from spatial practices of a new generation of tourists in Asia. Key words: Zhuhai, Macau, tourism, heritage, eco-city Producing a region to play n The paper investigates the transformation of the emerging cross-boundary tourism region Macau-Zhuhai in the Pearl River Delta (PRD). The investigation departs from Sheller and Urry’s observation of Places to Play/Places in Play (Sheller & Urry, 2004) which allows capturing the way how cities re-invent themselves to attract investments, tourists, and residents, and how, at the same time, they can become exposed to forces which undermine the qualities which originally made them attractive. -

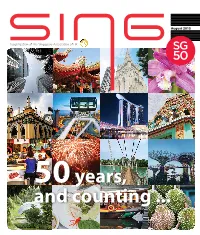

50Years, and Counting

August 2015 A publication of The Singapore Association of HK 50 years, and counting ... LSC ad_op.pdf 1 8/7/15 12:22 pm C C M M Y Y CM CM MY MY CY CY CMY CMY K K A publication of The Singapore Association of HK contents August 2015 Chairman’s message P6 Editor’s note A strict land ofP8 paradoxes HK FACT FILES P58 Useful info P10 P68 Cost of living Meeting of minds P72 Transportation P80 Shipping & relocation P84 Accommodation P16 P98 Education Celebrating SG50 P108 Kids’ activities P126 Eating out Eat, drink andP20 be merry Twin hubs – why Singaporean banks are movingP22 to the HKSAR PROFILES Lynette Tiong: P26 All in the family SPECIAL P30 FEATURES SIS: Nurturing Hellen Teo: brighter futures Love takes time P118 P34 Motivating your child to read P122 SG v HK P38 What Singaporeans say P44 Who comes up top in transport? P50 Natalie Yue: Happy in Singapore P54 Jack Lee: Learning his ABCs 06SING August 2015 A publication of The Singapore Association of HK MESSAGE SING is published by Ren Publishing (HK) Ltd for The Singapore Association of Hong Kong to provide logistics support for their canned commemorate SG50. FROM THE food event, which will deliver much-needed Editor: Jennifer Tan, Vice Chair, SAHK supplies to the underprivileged through SAHK the Chicken Soup Foundation. SIS was a big supporter of SA Ball 2015, with the SIS CHAIRMAN Choir providing a wonderful performance during the event. We will also continue to Tan Thean Peng Dear fellow Singaporeans and friends, work with various universities to reach out to Managing Director: Singaporean students studying in Hong Kong. -

Hong Kong Macau Taiwan China Philippines 日本経済新聞国際版が

日本経済新聞国際版が読めるホテル 更新日: 2019/6/5 日本経済新聞国際版は下記のホテルでお読みいただけます。 Hong Kong Macau Taiwan China Philippines Conrad Hong Kong Galaxy Macau™ Regent Taipei Okura Garden Hotel Shanghai Makati Shangri-La, Manila Cordis, Hong Kong MGM Macau Sheraton Taipei Shangri-La Hotel, Dalian New World Makati Hotel Four Seasons Hotel Hong Kong Wynn Macau Mandarin Oriental, Taipei New Otani Chang Fu Gong Pan Pacific Manila Hotel Gateway, Hong Kong Gloria Prince Hotel Taipei Garden Hotel, Guangzhou Gloucester Luk Kwok Hotel The Sherwood Taipei Jing An Shangri-La, West Shanghai Grand Hyatt Hong Kong Evergreen Laurel Hotel Taipei Pudong Shangri-La, East Shanghai Harbour Grand Hong Kong Hotel Royal-Nikko Taipei Hotel Nikko Shanghai Hotel Panorama by Rhombus Hotel Royal Hsinchu Hyatt Regency Hong Kong, Tsim Sha Tsui THE Tango Taipei LinSen InterContinental Grand Stanford Hong Kong THE Tango Taipei NanShi InterContinental Hong Kong Imperial Hotel Taipei Island Shangri-La, Hong Kong The Howard Plaza Hotel Taipei JW Marriott Hotel Hong Kong The Okura Prestige Taipei Kerry Hotel, Hong Kong Shangri-La's Far Eastern Plaza Hotel, Taipei Kowloon Shangri-La, Hong Kong Shangri-La's Far Eastern Plaza Hotel, Tainan Mandarin Oriental, Hong Kong The Westin Taipei Marco Polo Hong Kong Hotel K Hotels TaipeiⅡ New World Millennium HongKong Hotel K Hotel Taipei Songjiang Novotel Hong Kong Century Hotel Miramar Hotel Hsinchu Prince Hotel, Hong Kong The Landis Taipei Rosewood Hong Kong Sheraton Hong Kong Hotel and Towers The HabourView Place Kerry Hotel, Hong Kong The Landmark Mandarin Oriental,Hong Kong The Langham Hotel Hong Kong The Murray, Hong Kong, a Niccolo Hotel The Peninsula Hong Kong The Ritz Carlton, Hong Kong The Royal Pacific Hotel & Towers Copyright © NIKKEI GROUP ASIA PTE LTD. -

Annual Report 2010 Tel (852) 2879 1288 Fax (852) 2827 1338 U a L R E P O R T 2 0 1 0

CHAMPION R CHAMPION ea L ESTATE INVESTMENT TR INVESTMENT ESTATE L U ST CHAMPION REIT 3008 Great Eagle Centre, 23 Harbour Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong ANN AnnUAL Report 2010 Tel (852) 2879 1288 Fax (852) 2827 1338 www.ChampionReit.com U A L REPORT 2010 REPORT Champion Real Estate Investment Trust (stock code 2778) is a Hong Kong collective investment scheme authorised under section 104 of the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Chapter 571 of the Laws of Hong Kong) GLOBAL BEST PRACTICES AND STANDARDS Champion REIT is committed to attaining global best practices and standards. Champion REIT’s interpretation of ‘global best practices and standards’ is based upon six key principles: • Ensuring the Basis for an Efficient Corporate Governance Framework • The Rights of Unitholders and Key Ownership Functions • The Equitable Treatment of Unitholders • The Role of Stakeholders in Corporate Governance • Disclosure and Transparency • The Responsibilities of the Board The REIT Manager has adopted compliance TRUST PROFILE procedures and applies them to ensure the sound Champion Real Estate Investment Trust is a trust management and operation of Champion REIT. The formed to own and invest in income-producing office current corporate governance framework emphasizes and retail properties and is one of Asia’s 10 largest accountability to all Unitholders, resolution of REITs by market capitalization. The Trust’s focus is conflict of interest issues, transparency in reporting, on Grade-A commercial properties in prime locations. compliance with relevant regulations and sound It currently offers investors direct exposure to 2.85 operating and investing procedures. million sq. ft. of prime office and retail floor area by way of two landmark properties in Hong Kong, Citibank Plaza and Langham Place, one on each side of the Victoria Harbour.