Octopus Vulgaris: Optimizing Energy Gain Through Prey Selection and Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impact Damage and Repair in Shells of the Limpet Patella Vulgata David Taylor

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2016) 219, 3927-3935 doi:10.1242/jeb.149880 RESEARCH ARTICLE Impact damage and repair in shells of the limpet Patella vulgata David Taylor ABSTRACT can be a major cause of lethal damage. Shanks and Wright (1986) Experiments and observations were carried out to investigate the demonstrated the destructive power of wave-borne missiles by response of the Patella vulgata limpet shell to impact. Dropped-weight setting up targets to record impacts in a given area. They studied four impact tests created damage that usually took the form of a hole in the limpet species, finding that they were much more likely to be lost in shell’s apex. Similar damage was found to occur naturally, a location where there were many movable rocks and pebbles presumably as a result of stones propelled by the sea during compared with a location consisting largely of solid rock mass. storms. Apex holes were usually fatal, but small holes were Examining the populations over a one year period, and making a sometimes repaired, and the repaired shell was as strong as the number of assumptions about size distributions and growth rates, original, undamaged shell. The impact strength (energy to failure) of they estimated that 47% of shells were destroyed in the former shells tested in situ was found to be 3.4-times higher than that of location, compared with 7% in the latter (Shanks and Wright, 1986). empty shells found on the beach. Surprisingly, strength was not Another study (Cadée, 1999) reported that impact damage by ice affected by removing the shell from its home location, or by removing blocks and stones was the major cause of damage to the limpet the limpet from the shell and allowing the shell to dry out. -

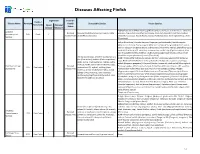

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Marine Shelled Molluscs

Mar Biol DOI 10.1007/s00227-013-2219-3 ORIGINAL PAPER Impacts of ocean acidification on marine shelled molluscs Fre´de´ric Gazeau • Laura M. Parker • Steeve Comeau • Jean-Pierre Gattuso • Wayne A. O’Connor • Sophie Martin • Hans-Otto Po¨rtner • Pauline M. Ross Received: 18 January 2013 / Accepted: 15 March 2013 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Abstract Over the next century, elevated quantities of ecosystem services including habitat structure for benthic atmospheric CO2 are expected to penetrate into the oceans, organisms, water purification and a food source for other causing a reduction in pH (-0.3/-0.4 pH unit in the organisms. The effects of ocean acidification on the growth surface ocean) and in the concentration of carbonate ions and shell production by juvenile and adult shelled molluscs (so-called ocean acidification). Of growing concern are the are variable among species and even within the same impacts that this will have on marine and estuarine species, precluding the drawing of a general picture. This organisms and ecosystems. Marine shelled molluscs, which is, however, not the case for pteropods, with all species colonized a large latitudinal gradient and can be found tested so far, being negatively impacted by ocean acidifi- from intertidal to deep-sea habitats, are economically cation. The blood of shelled molluscs may exhibit lower and ecologically important species providing essential pH with consequences for several physiological processes (e.g. respiration, excretion, etc.) and, in some cases, increased mortality in the long term. While fertilization Communicated by S. Dupont. may remain unaffected by elevated pCO2, embryonic and Fre´de´ric Gazeau and Laura M. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Moluscos

A Chave Os nomes galegos dos moluscos 2017 Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (2017): Nomes galegos dos moluscos recomendados pola Chave. http://www.achave.gal/wp-content/uploads/achave_osnomesgalegosdos_moluscos.pdf 1 Notas introdutorias O que contén este documento Neste documento fornécense denominacións para as especies de moluscos galegos (e) ou europeos, e tamén para algunhas das especies exóticas máis coñecidas (xeralmente no ámbito divulgativo, por causa do seu interese científico ou económico, ou por seren moi comúns noutras áreas xeográficas). En total, achéganse nomes galegos para 534 especies de moluscos. A estrutura En primeiro lugar preséntase unha clasificación taxonómica que considera as clases, ordes, superfamilias e familias de moluscos. Aquí apúntase, de maneira xeral, os nomes dos moluscos que hai en cada familia. A seguir vén o corpo do documento, onde se indica, especie por especie, alén do nome científico, os nomes galegos e ingleses de cada molusco (nalgún caso, tamén, o nome xenérico para un grupo deles). Ao final inclúese unha listaxe de referencias bibliográficas que foron utilizadas para a elaboración do presente documento. Nalgunhas desas referencias recolléronse ou propuxéronse nomes galegos para os moluscos, quer xenéricos quer específicos. Outras referencias achegan nomes para os moluscos noutras linguas, que tamén foron tidos en conta. Alén diso, inclúense algunhas fontes básicas a respecto da metodoloxía e dos criterios terminolóxicos empregados. 2 Tratamento terminolóxico De modo moi resumido, traballouse nas seguintes liñas e cos seguintes criterios: En primeiro lugar, aprofundouse no acervo lingüístico galego. A respecto dos nomes dos moluscos, a lingua galega é riquísima e dispomos dunha chea de nomes, tanto específicos (que designan un único animal) como xenéricos (que designan varios animais parecidos). -

Shells Shells Are the Remains of a Group of Animals Called Molluscs

Inspire - Educate – Showcase Shells Shells are the remains of a group of animals called molluscs. Bivalves Molluscs are soft-bodied animals inhabiting marine, land and Bivalves are molluscs made up of two shells joined by a hinge with freshwater habitats. The shells we commonly come across on the interlocking teeth. The shells are usually held together by a tough beach belong to one of two groups of molluscs, either gastropods ligament. These creatures also have a set of two tubes which which have one shell, or bivalves which have two shells. The material sometimes stick out from shell allowing the animal to breathe and making up the shell is secreted by special glands of the animal living feed. within it. Some commonly known bivalves include clams, cockles, mussels, scallops and oysters. Can you think of any others? Oysters and mussels attach themselves to solid objects such as jetty pylons or rocks on the sea floor and filter feed by taking Gastropod = One Shell Bivalve = Two Shells water into one tube and removing the tiny particles of plankton from the water. In contrast, scallops and cockles are moving Particular shell shapes have been adapted to suit the habitat and bivalves and can either swim through the conditions in which the animals live, helping them to survive. The water or pull themselves through the sand wedge shape of a cockle shell allows them to easily burrow into the with their muscular, soft bodies. sand. Ribs, folds and frills on many molluscs help to strengthen the shell and provide extra protection from predators. -

Octopus Consciousness: the Role of Perceptual Richness

Review Octopus Consciousness: The Role of Perceptual Richness Jennifer Mather Department of Psychology, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB T1K 3M4, Canada; [email protected] Abstract: It is always difficult to even advance possible dimensions of consciousness, but Birch et al., 2020 have suggested four possible dimensions and this review discusses the first, perceptual richness, with relation to octopuses. They advance acuity, bandwidth, and categorization power as possible components. It is first necessary to realize that sensory richness does not automatically lead to perceptual richness and this capacity may not be accessed by consciousness. Octopuses do not discriminate light wavelength frequency (color) but rather its plane of polarization, a dimension that we do not understand. Their eyes are laterally placed on the head, leading to monocular vision and head movements that give a sequential rather than simultaneous view of items, possibly consciously planned. Details of control of the rich sensorimotor system of the arms, with 3/5 of the neurons of the nervous system, may normally not be accessed to the brain and thus to consciousness. The chromatophore-based skin appearance system is likely open loop, and not available to the octopus’ vision. Conversely, in a laboratory situation that is not ecologically valid for the octopus, learning about shapes and extents of visual figures was extensive and flexible, likely consciously planned. Similarly, octopuses’ local place in and navigation around space can be guided by light polarization plane and visual landmark location and is learned and monitored. The complex array of chemical cues delivered by water and on surfaces does not fit neatly into the components above and has barely been tested but might easily be described as perceptually rich. -

Freshwater Mussels "Do You Mean Muscles?" Actually, We're Talking About Little Animals That Live in the St

Our Mighty River Keepers Freshwater Mussels "Do you mean muscles?" Actually, we're talking about little animals that live in the St. Lawrence River called "freshwater mussels." "Oh, like zebra mussels?" Exactly! Zebra mussels are a non-native and invasive type of freshwater mussel that you may have already heard about. Zebra mussels are from faraway lakes and rivers in Europe and Asia; they travelled here in the ballast of cargo ships. When non-native: not those ships came into the St. Lawrence River, they dumped the originally belonging in a zebra mussels into the water without realizing it. Since then, particular place the zebra mussels have essentially taken over the river. invasive: tending to The freshwater mussels which are indigenous, or native, to the spread harmfully St. Lawrence River, are struggling to keep up with the growing number of invasive zebra mussels. But we'll talk more about ballast: heavy material that, later. (like stones, lead, or even water) placed in the bottom of a ship to For now, let's take a closer look at what it improve its stability means to be a freshwater mussel... indigenous: originally belonging in a particular place How big is a zebra mussel? 1 "What is a mussel?" Let's classify it to find out! We use taxonomy (the study of naming and classifying groups of organisms based on their characteristics) as a way to organize all the organisms of our world inside our minds. Grouping mussels with organisms that are similar can help us answer the question "What KKingdom:ingdom: AAnimalianimalia is a mussel?" Start at the top of our flow chart with the big group called the Kingdom: Animalia (the Latin way to say "animals"). -

Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus Dofleini) Care Manual

Giant Pacific Octopus Insert Photo within this space (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual CREATED BY AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxonomic Advisory Group IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA Animal Welfare Committee Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxon Advisory Group (AITAG) (2014). Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. Original Completion Date: September 2014 Dedication: This work is dedicated to the memory of Roland C. Anderson, who passed away suddenly before its completion. No one person is more responsible for advancing and elevating the state of husbandry of this species, and we hope his lifelong body of work will inspire the next generation of aquarists towards the same ideals. Authors and Significant Contributors: Barrett L. Christie, The Dallas Zoo and Children’s Aquarium at Fair Park, AITAG Steering Committee Alan Peters, Smithsonian Institution, National Zoological Park, AITAG Steering Committee Gregory J. Barord, City University of New York, AITAG Advisor Mark J. Rehling, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Roland C. Anderson, PhD Reviewers: Mike Brittsan, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Paula Carlson, Dallas World Aquarium Marie Collins, Sea Life Aquarium Carlsbad David DeNardo, New York Aquarium Joshua Frey Sr., Downtown Aquarium Houston Jay Hemdal, Toledo -

Eight Arms, with Attitude

The link information below provides a persistent link to the article you've requested. Persistent link to this record: Following the link below will bring you to the start of the article or citation. Cut and Paste: To place article links in an external web document, simply copy and paste the HTML below, starting with "<a href" To continue, in Internet Explorer, select FILE then SAVE AS from your browser's toolbar above. Be sure to save as a plain text file (.txt) or a 'Web Page, HTML only' file (.html). In Netscape, select FILE then SAVE AS from your browser's toolbar above. Record: 1 Title: Eight Arms, With Attitude. Authors: Mather, Jennifer A. Source: Natural History; Feb2007, Vol. 116 Issue 1, p30-36, 7p, 5 Color Photographs Document Type: Article Subject Terms: *OCTOPUSES *ANIMAL behavior *ANIMAL intelligence *PLAY *PROBLEM solving *PERSONALITY *CONSCIOUSNESS in animals Abstract: The article offers information on the behavior of octopuses. The intelligence of octopuses has long been noted, and to some extent studied. But in recent years, play, and problem-solving skills has both added to and elaborated the list of their remarkable attributes. Personality is hard to define, but one can begin to describe it as a unique pattern of individual behavior that remains consistent over time and in a variety of circumstances. It will be hard to say for sure whether octopuses possess consciousness in some simple form. Full Text Word Count: 3643 ISSN: 00280712 Accession Number: 23711589 Persistent link to this http://0-search.ebscohost.com.library.bennington.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=23711589&site=ehost-live -

First Record of the Mediterranean Mussel Mytilus Galloprovincialis (Bivalvia, Mytilidae) in Brazil

ARTICLE First record of the Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis (Bivalvia, Mytilidae) in Brazil Carlos Eduardo Belz¹⁵; Luiz Ricardo L. Simone²; Nelson Silveira Júnior³; Rafael Antunes Baggio⁴; Marcos de Vasconcellos Gernet¹⁶ & Carlos João Birckolz¹⁷ ¹ Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR), Centro de Estudos do Mar (CEM), Laboratório de Ecologia Aplicada e Bioinvasões (LEBIO). Pontal do Paraná, PR, Brasil. ² Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Museu de Zoologia (MZUSP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1397-9823. E-mail: [email protected] ³ Nixxen Comercio de Frutos do Mar LTDA. Florianópolis, SC, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8037-5141. E-mail: [email protected] ⁴ Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR), Departamento de Zoologia (DZOO), Laboratório de Ecologia Molecular e Parasitologia Evolutiva (LEMPE). Curitiba, PR, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8307-1426. E-mail: [email protected] ⁵ ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2381-8185. E-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) ⁶ ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5116-5719. E-mail: [email protected] ⁷ ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7896-1018. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The genus Mytilus comprises a large number of bivalve mollusk species distributed throughout the world and many of these species are considered invasive. In South America, many introductions of species of this genus have already taken place, including reports of hybridization between them. Now, the occurrence of the Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis is reported for the first time from the Brazilian coast. Several specimens of this mytilid were found in a shellfish growing areas in Florianópolis and Palhoça, Santa Catarina State, Brazil. -

Defensive Behaviors of Deep-Sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy

Defensive Behaviors of Deep-sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy by Stephanie Lynn Bush A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Roy L. Caldwell, Chair Professor David R. Lindberg Professor George K. Roderick Dr. Bruce H. Robison Fall, 2009 Defensive Behaviors of Deep-sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy © 2009 by Stephanie Lynn Bush ABSTRACT Defensive Behaviors of Deep-sea Squids: Ink Release, Body Patterning, and Arm Autotomy by Stephanie Lynn Bush Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Roy L. Caldwell, Chair The deep sea is the largest habitat on Earth and holds the majority of its’ animal biomass. Due to the limitations of observing, capturing and studying these diverse and numerous organisms, little is known about them. The majority of deep-sea species are known only from net-caught specimens, therefore behavioral ecology and functional morphology were assumed. The advent of human operated vehicles (HOVs) and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) have allowed scientists to make one-of-a-kind observations and test hypotheses about deep-sea organismal biology. Cephalopods are large, soft-bodied molluscs whose defenses center on crypsis. Individuals can rapidly change coloration (for background matching, mimicry, and disruptive coloration), skin texture, body postures, locomotion, and release ink to avoid recognition as prey or escape when camouflage fails. Squids, octopuses, and cuttlefishes rely on these visual defenses in shallow-water environments, but deep-sea cephalopods were thought to perform only a limited number of these behaviors because of their extremely low light surroundings. -

List of Bivalve Molluscs from British Columbia, Canada

List of Bivalve Molluscs from British Columbia, Canada Compiled by Robert G. Forsyth Research Associate, Invertebrate Zoology, Royal BC Museum, 675 Belleville Street, Victoria, BC V8W 9W2; [email protected] Rick M. Harbo Research Associate, Invertebrate Zoology, Royal BC Museum, 675 Belleville Street, Victoria BC V8W 9W2; [email protected] Last revised: 11 October 2013 INTRODUCTION Classification rankings are constantly under debate and review. The higher classification utilized here follows Bieler et al. (2010). Another useful resource is the online World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS; Gofas 2013) where the traditional ranking of Pteriomorphia, Palaeoheterodonta and Heterodonta as subclasses is used. This list includes 237 bivalve species from marine and freshwater habitats of British Columbia, Canada. Marine species (206) are mostly derived from Coan et al. (2000) and Carlton (2007). Freshwater species (31) are from Clarke (1981). Common names of marine bivalves are from Coan et al. (2000), who adopted most names from Turgeon et al. (1998); common names of freshwater species are from Turgeon et al. (1998). Changes to names or additions to the fauna since these two publications are marked with footnotes. Marine groups are in black type, freshwater taxa are in blue. Introduced (non-indigenous) species are marked with an asterisk (*). Marine intertidal species (n=84) are noted with a dagger (†). Quayle (1960) published a BC Provincial Museum handbook, The Intertidal Bivalves of British Columbia. Harbo (1997; 2011) provided illustrations and descriptions of many of the bivalves found in British Columbia, including an identification guide for bivalve siphons and “shows”. Lamb & Hanby (2005) also illustrated many species.