Beyond the Methodological Gold Standards of Behavioral Research: Considerations for Practice and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should the Randomistas (Continue To) Rule?

Should the Randomistas (Continue to) Rule? Martin Ravallion Abstract The rising popularity of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in development applications has come with continuing debates on the pros and cons of this approach. The paper revisits the issues. While RCTs have a place in the toolkit for impact evaluation, an unconditional preference for RCTs as the “gold standard” is questionable. The statistical case is unclear on a priori grounds; a stronger ethical defense is often called for; and there is a risk of distorting the evidence-base for informing policymaking. Going forward, pressing knowledge gaps should drive the questions asked and how they are answered, not the methodological preferences of some researchers. The gold standard is the best method for the question at hand. Keywords: Randomized controlled trials, bias, ethics, external validity, ethics, development policy JEL: B23, H43, O22 Working Paper 492 August 2018 www.cgdev.org Should the Randomistas (Continue to) Rule? Martin Ravallion Department of Economics, Georgetown University François Roubaud encouraged the author to write this paper. For comments the author is grateful to Sarah Baird, Mary Ann Bronson, Caitlin Brown, Kevin Donovan, Markus Goldstein, Miguel Hernan, Emmanuel Jimenez, Madhulika Khanna, Nishtha Kochhar, Andrew Leigh, David McKenzie, Berk Özler, Dina Pomeranz, Lant Pritchett, Milan Thomas, Vinod Thomas, Eva Vivalt, Dominique van de Walle and Andrew Zeitlin. Staff of the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation kindly provided an update to their database on published impact evaluations and helped with the author’s questions. Martin Ravallion, 2018. “Should the Randomistas (Continue to) Rule?.” CGD Working Paper 492. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. -

Getting Off the Gold Standard for Causal Inference

Getting Off the Gold Standard for Causal Inference Robert Kubinec New York University Abu Dhabi March 1st, 2020 Abstract I argue that social scientific practice would be improved if we abandoned the notion that a gold standard for causal inference exists. Instead, we should consider the three main in- ference modes–experimental approaches and the counterfactual theory, large-N observational studies, and qualitative process-tracing–as observable indicators of an unobserved latent con- struct, causality. Under ideal conditions, any of these three approaches provide strong, though not perfect, evidence of an important part of what we mean by causality. I also present the use of statistical entropy, or information theory, as a possible yardstick for evaluating research designs across the silver standards. Rather than dichotomize studies as either causal or descrip- tive, the concept of relative entropy instead emphasizes the relative causal knowledge gained from a given research finding. Word Count: 9,823 words 1 You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold. – William Jennings Bryan, July 8, 1896 The renewed attention to causal identification in the last twenty years has elevated the status of the randomized experiment to the sine qua non gold standard of the social sciences. Nonetheless, re- search employing observational data, both qualitative and quantitative, continues unabated, albeit with a new wrinkle: because observational data cannot, by definition, assign cases to receive causal treatments, any conclusions from these studies must be descriptive, rather than causal. However, even though this new norm has received widespread adoption in the social sciences, the way that so- cial scientists discuss and interpret their data often departs from this clean-cut approach. -

Assessing the Accuracy of a New Diagnostic Test When a Gold Standard Does Not Exist Todd A

UW Biostatistics Working Paper Series 10-1-1998 Assessing the Accuracy of a New Diagnostic Test When a Gold Standard Does Not Exist Todd A. Alonzo University of Southern California, [email protected] Margaret S. Pepe University of Washington, [email protected] Suggested Citation Alonzo, Todd A. and Pepe, Margaret S., "Assessing the Accuracy of a New Diagnostic Test When a Gold Standard Does Not Exist" (October 1998). UW Biostatistics Working Paper Series. Working Paper 156. http://biostats.bepress.com/uwbiostat/paper156 This working paper is hosted by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress) and may not be commercially reproduced without the permission of the copyright holder. Copyright © 2011 by the authors 1 Introduction Medical diagnostic tests play an important role in health care. New diagnostic tests for detecting viral and bacterial infections are continually being developed. The performance of a new diagnostic test is ideally evaluated by comparison with a perfect gold standard test (GS) which assesses infection status with certainty. Many times a perfect gold standard does not exist and a reference test or imperfect gold standard must be used instead. Although statistical methods and techniques are well established for assessing the accuracy of a new diagnostic test when a perfect gold standard exists, such methods are lacking for settings where a gold standard is not available. In this paper we will review some existing approaches to this problem and propose an alternative approach. To fix ideas we consider a specific example. Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common sexually transmitted bacterial pathogen. In women Chlamydia trachomatis can result in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) which can lead to infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and life-threatening ectopic pregnancy. -

Memorandum Explaining Basis for Declining Request for Emergency Use Authorization for Emergency Use of Hydroxychloroquine Sulfate

Memorandum Explaining Basis for Declining Request for Emergency Use Authorization for Emergency Use of Hydroxychloroquine Sulfate On July 6, 2020, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) received a submission from Dr. William W. O’Neill, co-signed by Dr. John E. McKinnon1, Dr. Dee Dee Wang, and Dr. Marcus J. Zervos requesting, among other things, emergency use authorization (EUA) of hydroxychloroquine sulfate (HCQ) for prevention (pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis) and treatment of “early COVID-19 infections”. We interpret the term “early COVID-19 infections” to mean individuals with 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) who are asymptomatic or pre- symptomatic or have mild illness.2 The statutory criteria for issuing an EUA are set forth in Section 564(c) of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act). Specifically, the FDA must determine, among other things, that “based on the totality of scientific information available to [FDA], including data from adequate and well-controlled clinical trials, if available,” it is reasonable to believe that the product may be effective in diagnosing, treating, or preventing a serious or life-threatening disease or condition caused by the chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear agent; that the known and potential benefits, when used to diagnose, treat, or prevent such disease or condition, outweigh the known and potential risks of the product; and that there are no adequate, approved, and available alternatives. FDA scientific review staff have reviewed available information derived from clinical trials and observational studies investigating the use of HCQ in the prevention or the treatment of COVID- 19. -

Randomized Controlled Trials, Development Economics and Policy Making in Developing Countries

Randomized Controlled Trials, Development Economics and Policy Making in Developing Countries Esther Duflo Department of Economics, MIT Co-Director J-PAL [Joint work with Abhijit Banerjee and Michael Kremer] Randomized controlled trials have greatly expanded in the last two decades • Randomized controlled Trials were progressively accepted as a tool for policy evaluation in the US through many battles from the 1970s to the 1990s. • In development, the rapid growth starts after the mid 1990s – Kremer et al, studies on Kenya (1994) – PROGRESA experiment (1997) • Since 2000, the growth have been very rapid. J-PAL | THE ROLE OF RANDOMIZED EVALUATIONS IN INFORMING POLICY 2 Cameron et al (2016): RCT in development Figure 1: Number of Published RCTs 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 Publication Year J-PAL | THE ROLE OF RANDOMIZED EVALUATIONS IN INFORMING POLICY 3 BREAD Affiliates doing RCT Figure 4. Fraction of BREAD Affiliates & Fellows with 1 or more RCTs 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 1980 or earlier 1981-1990 1991-2000 2001-2005 2006-today * Total Number of Fellows and Affiliates is 166. PhD Year J-PAL | THE ROLE OF RANDOMIZED EVALUATIONS IN INFORMING POLICY 4 Top Journals J-PAL | THE ROLE OF RANDOMIZED EVALUATIONS IN INFORMING POLICY 5 Many sectors, many countries J-PAL | THE ROLE OF RANDOMIZED EVALUATIONS IN INFORMING POLICY 6 Why have RCT had so much impact? • Focus on identification of causal effects (across the board) • Assessing External Validity • Observing Unobservables • Data collection • Iterative Experimentation • Unpack impacts J-PAL | THE ROLE OF RANDOMIZED EVALUATIONS IN INFORMING POLICY 7 Focus on Identification… across the board! • The key advantage of RCT was perceived to be a clear identification advantage • With RCT, since those who received a treatment are randomly selected in a relevant sample, any difference between treatment and control must be due to the treatment • Most criticisms of experiment also focus on limits to identification (imperfect randomization, attrition, etc. -

Evaluating Diagnostic Tests in the Absence of a Gold Standard

Evaluating Diagnostic Tests in the Absence of a Gold Standard Nandini Dendukuri Departments of Medicine & Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health, McGill University; Technology Assessment Unit, McGill University Health Centre Advanced TB diagnostics course, Montreal, July 2011 Evaluating Diagnostic Tests in the Absence of a Gold Standard • An area where we are still awaiting a solution – We are still working on methods for Phase 0 studies • A number of methods have appeared in the pipeline – Some have been completely discredited (e.g. Discrepant Analysis) – Some are more realistic but have had scale-up problems due to mathematical complexity and lack of software (e.g. Latent Class Analysis) – Some in-between solutions seem easy to use, but their inherent biases are poorly understood (e.g. Composite reference standards) • Not yet at the stage where you can stick your data into a machine and get accurate results in 2 hours No gold-standard for many types of TB • Example 1: TB pleuritis: – Conventional tests have less than perfect sensitivity* Microscopy of the pleural fluid <5% Culture of pleural fluid 24 to 58% Biopsy of pleural tissue ~ 86% + culture of biopsy material – Most conventional tests have good, though not perfect specificity ranging from 90-100% * Source: Pai et al., BMC Infectious Diseases, 2004 No gold-standard for many types of TB • Example 2: Latent TB Screening/Diagnosis: – Traditionally based on Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) • TST has poor specificity* due to cross-reactivity with BCG vaccination and infection -

Screening for Alcohol Problems, What Makes a Test Effective?

Screening for Alcohol Problems What Makes a Test Effective? Scott H. Stewart, M.D., and Gerard J. Connors, Ph.D. Screening tests are useful in a variety of settings and contexts, but not all disorders are amenable to screening. Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and other drinking problems are a major cause of morbidity and mortality and are prevalent in the population; effective treatments are available, and patient outcome can be improved by early detection and intervention. Therefore, the use of screening tests to identify people with or at risk for AUDs can be beneficial. The characteristics of screening tests that influence their usefulness in clinical settings include their validity, sensitivity, and specificity. Appropriately conducted screening tests can help clinicians better predict the probability that individual patients do or do not have a given disorder. This is accomplished by qualitatively or quantitatively estimating variables such as positive and negative predictive values of screening in a population, and by determining the probability that a given person has a certain disorder based on his or her screening results. KEY WORDS: AOD (alcohol and other drug) use screening method; identification and screening for AODD (alcohol and other drug disorders); risk assessment; specificity of measurement; sensitivity of measurement; predictive validity; Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) he term “screening” refers to the confirm whether or not they have the application of a test to members disorder. When a screening test indicates SCOTT H. STEWART, M.D., is an assistant Tof a population (e.g., all patients that a patient may have an AUD or professor in the Department of Medicine, in a physician’s practice) to estimate their other drinking problem, the clinician School of Medicine and Biomedical probability of having a specific disorder, might initiate a brief intervention and Sciences at the State University of New such as an alcohol use disorder (AUD) arrange for clinical followup, which York at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York. -

Adaptive Platform Trials

Corrected: Author Correction PERSPECTIVES For example, APTs require considerable OPINION pretrial evaluation through simulation to assess the consequences of patient selection Adaptive platform trials: definition, and stratification, organization of study arms, within- trial adaptations, overarching statistical modelling and miscellaneous design, conduct and reporting issues such as modelling for drift in the standard of care used as a control over time. considerations In addition, once APTs are operational, transparent reporting of APT results requires The Adaptive Platform Trials Coalition accommodation for the fact that estimates of efficacy are typically derived from a model Abstract | Researchers, clinicians, policymakers and patients are increasingly that uses information from parts of the interested in questions about therapeutic interventions that are difficult or costly APT that are ongoing, and may be blinded. to answer with traditional, free- standing, parallel- group randomized controlled As several groups are launching APTs, trials (RCTs). Examples include scenarios in which there is a desire to compare the Adaptive Platform Trials Coalition was multiple interventions, to generate separate effect estimates across subgroups of formed to generate standardized definitions, share best practices, discuss common design patients with distinct but related conditions or clinical features, or to minimize features and address oversight and reporting. downtime between trials. In response, researchers have proposed new RCT designs This paper is based on the findings from such as adaptive platform trials (APTs), which are able to study multiple the first meeting of this coalition, held in interventions in a disease or condition in a perpetual manner, with interventions Boston, Massachusetts in May 2017, with entering and leaving the platform on the basis of a predefined decision algorithm. -

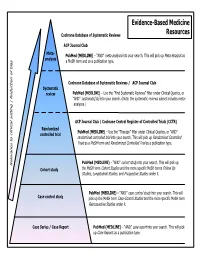

Common Types of Questions: Types of Study Designs

Evidence-Based Medicine Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Resources ACP Journal Club Meta- is as PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” meta-analysis into your search. This will pick up Meta-Analys analysis s a MeSH term and as a publication type. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews / ACP Journal Club Systematic review PubMed (MEDLINE) – Use the ”Find Systematic Reviews” filter under Clinical Queries, or “AND” systematic[sb] into your search. (Note: the systematic reviews subset includes meta- analyses.) tting | Reduction of bia ACP Journal Club / Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR) Randomized PubMed (MEDLINE) – Use the “Therapy” filter under Clinical Queries, or “AND” controlled trial randomized controlled trial into your search. This will pick up Randomized Controlled Trials as a MeSH term and Randomized Controlled Trial as a publication type. PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” cohort study into your search. This will pick up Relevance to clinical se Cohort study the MeSH term Cohort Studies and the more specific MeSH terms Follow Up Studies, Longitudinal Studies, and Prospective Studies under it. PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” case control study into your search. This will Case control study pick up the MeSH term Case-Control Studies and the more specific MeSH term Retrospective Studies under it. Case Series / Case Report PubMed (MEDLINE) – “AND” case report into your search. This will pick up Case Reports as a publication type. COMMON TYPES OF QUESTIONS: TYPES OF STUDY DESIGNS: Therapy -- how to select treatments to offer patients that do more good A Meta-analysis takes a systematic review one step further by than harm and that are worth the efforts and costs of using them combining all the results using accepted statistical methodology. -

Efficient Adaptive Designs for Clinical Trials of Interventions for COVID-19

Efficient adaptive designs for clinical trials of interventions for COVID-19 Nigel Stallarda1, Lisa Hampsona*2, Norbert Benda3, Werner Brannath4, Tom Burnett5, Tim Friede6, Peter K. Kimani1, Franz Koenig7, Johannes Krisam8, Pavel Mozgunov5, Martin Posch7, James Wason9,10, Gernot Wassmer11, John Whitehead5, S. Faye Williamson5, Sarah Zohar12, Thomas Jakia5,10 1 Statistics and Epidemiology, Division of Health Sciences, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, UK. 2 Advanced Methodology and Data Science, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland 3 The Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM), Bonn, Germany. 4 Institute for Statistics, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany 5 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Lancaster University, UK. 6 Department of Medical Statistics, University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany. 7 Section of Medical Statistics, CeMSIIS, Medical University of Vienna, Austria. 8 Institute of Medical Biometry and Informatics, University of Heidelberg, Germany. 9 Population Health Sciences Institute, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. 10 MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 11 RPACT GbR, Sereetz, Germany 12 INSERM, Centre de Recherche des Cordeliers, Sorbonne Université, Université de Paris, France * Corresponding author. [email protected] a These authors contributed equally Abstract The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented response in terms of clinical research activity. An important part of this research has been focused on randomized controlled clinical trials to evaluate potential therapies for COVID-19. The results from this research need to be obtained as rapidly as possible. This presents a number of challenges associated with considerable uncertainty over the natural history of the disease and the number and characteristics of patients affected, and the emergence of new potential therapies. -

Assessing the Accuracy of Diagnostic Tests

Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry: first published as 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.218052 on 25 July 2018. Downloaded from Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 2018, Vol. 30, No. 3 • 207 • •BIOSTATISTICS IN PSYCHIATRY (45)• Assessing the Accuracy of Diagnostic Tests Fangyu LI, Hua HE* Summary: Gold standard tests are usually used for diagnosis of a disease, but the gold standard tests may not be always available or cannot be administrated due to many reasons such as cost, availability, ethical issues etc. In such cases, some instruments or screening tools can be used to diagnose the disease. However, before the screening tools can be applied, it is crucial to evaluate the accuracy of these screening tools compared to the gold standard tests. In this assay, we will discuss how to assess the accuracy of a diagnostic test through an example using R program. Key words: AUC; gold standard test; ROC analysis; ROC curve; sensitivity; specificity [Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2018; 30(3): 207-212. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.218052] 1. Introduction time-consuming. Because of the constraints of SCID, copyright. Mental disease is a significant cause of worldwide some easily administered screening tools, such as the morbidity, second to cardiovascular disease, based Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), the Beck on the estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Depression Inventory (BDI), and even simpler screening Study.[1] Among mental diseases, depression is now the tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ- 2, PHQ-9) were developed and admitted to patients leading cause of the global disability burden. -

Evaluation of Diagnostic Tests When There Is No Gold Standard Vol

Health Technology Assessment Health Technology Health Technology Assessment 2007; Vol. 11: No. 50 2007; 11: No. 50 Vol. Evaluation of diagnostic tests when there is no gold standard Evaluation of diagnostic tests when there is no gold standard. A review of methods AWS Rutjes, JB Reitsma, A Coomarasamy, KS Khan and PMM Bossuyt Feedback The HTA Programme and the authors would like to know your views about this report. The Correspondence Page on the HTA website (http://www.hta.ac.uk) is a convenient way to publish your comments. If you prefer, you can send your comments to the address below, telling us whether you would like us to transfer them to the website. We look forward to hearing from you. December 2007 The National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment, Mailpoint 728, Boldrewood, Health Technology Assessment University of Southampton, NHS R&D HTA Programme Southampton, SO16 7PX, UK. HTA Fax: +44 (0) 23 8059 5639 Email: [email protected] www.hta.ac.uk http://www.hta.ac.uk ISSN 1366-5278 HTA How to obtain copies of this and other HTA Programme reports. An electronic version of this publication, in Adobe Acrobat format, is available for downloading free of charge for personal use from the HTA website (http://www.hta.ac.uk). A fully searchable CD-ROM is also available (see below). Printed copies of HTA monographs cost £20 each (post and packing free in the UK) to both public and private sector purchasers from our Despatch Agents. Non-UK purchasers will have to pay a small fee for post and packing.