Nov. 13, 2017 Price $8.99

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

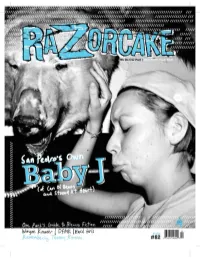

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Listen Up, Listen

20150601_postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 5/12/2015 7:08 PM Page 1 June 1, 2015 $4.99 COOKE on SALLY SATEL: The CDC’s E-cigarette Panic Pamela Geller MAC DONALD on Henry Olsen: Scott Walker’s Populist Appeal Baltimore LISTEN UP, LADIES The Unlikely Traditionalism of Millionaire Matchmaker PATTI STANGER by ELIANA JOHNSON www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 5/13/2015 2:37 PM Page 2 base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 5/11/2015 1:07 PM Page 3 TOC_QXP-1127940144.qxp 5/13/2015 2:05 PM Page 2 Contents JUNE 1, 2015 | VOLUME LXVII, NO. 10 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 29 Tocqueville’s Matchmaker Henry Olsen on Scott Walker Patti Stanger, host of Bravo TV’s The p. 22 Millionaire Matchmaker, looks like a feminist hero. She’s single, she’s rich, and she, as they say, has it all. It’s in BOOKS, ARTS her work as a matchmaker that things & MANNERS get tricky. The laws of love, she has 42 THE SOURCES OF AMERICAN found, have not bent to the arc of CONDUCT the feminist movement. Eliana Johnson Mario Loyola reviews The Obama Doctrine: American Grand Strategy Today, by Colin Dueck. COVER: RANDEE ST. NICHOLAS 43 LOST, NOT FORGOTTEN ARTICLES Joseph Postell reviews Our Lost Constitution: The Willful 18 FREE SPEECH WITHOUT APOLOGIES by Charl es C. W. Cooke Subversion of America’s When bullets start to fly, who cares who is their target? Founding Document, by Mike Lee. 20 A 2016 POLICY PREVIEW by Ramesh Ponnuru Taking a look at the GOP hopefuls’ nascent agendas. -

AMERICAN YACHTING ;-Rhg?>Y^O

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/americanyachtingOOsteprich THE AMERICAN SPORTSMAN'S LIBRARY EDITED BY CASPAR WHITNEY AMERICAN YACHTING ;-rhg?>y^o AMERICAN YACHTING BY W. p. STEPHENS Of TH£ UNfVERSITY Of NelD gork THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd. 1904 All rights reserved Copyright, 1904, By the MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up, electrotyped, and published April, 1904. Norwood Press Smith Co, J. S. Gushing & Co. — Berwick & Norwood^ Mass.f U.S.A. INTRODUCTION In spite of the utilitarian tendencies of the present age, it is fortunately no longer necessary to argue in behalf of sport; even the busiest of busy Americans have at last learned the neces- sity for a certain amount of relaxation and rec- reation, and that the best way to these lies in the pursuit of some form of outdoor sport. While each has its stanch adherents, who pro- claim its superiority to all others, the sport of yachting can perhaps show as much to its credit as any. As a means to perfect physical development, one great point in all sports, it has the advantage of being followed outdoors in the bracing atmos- phere of the sea; and while it involves severe physical labor and at times actual hardships, it fits its devotees to withstand and enjoy both. In the matter of competition, the salt and savor of all sport, yachting opens a wide and varied field. In cruising there is a constant strife 219316 vi Introduction with the elements, and in racing there is the contest of brain and hand against those of equal adversaries. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

Mikky Ekko Has Come Home. He Recorded His 2015 Debut Album

Mikky Ekko has come home. He recorded his 2015 debut album, Time, in places as far-flung as London, Stockholm, and Los Angeles, plus any point on the compass where inspiration struck while he was on tour with Justin Timberlake, One Republic and Jessie Ware. But he wanted to record Fame, his next album, in the city that had proved both a permanent address and an inspiration for him since moving there in 2005 to attend college. It’s said that people have lucky cities, a geographic location where they seem to flourish or feel that they are their best selves. Although born in Shreveport, Louisiana, with its rich history of country rock and electric blues, Ekko found such a place in Nashville. It allowed him the freedom to be who he wanted to be — starting with those early gigs he played at 12th and Porter with slashes of red painted across his chiseled face. It informed the haunting music of his largely a cappella 2009 dreamscape Strange Fruit, a five-song EP he recorded while still a student at nearby Middle Tennessee State University that had far more in common with Brian Eno than it did Billie Holiday. A restless creator — sometimes writing two songs a day, starting most days at 4:45 am — Ekko quickly followed up Strange Fruit with two companion EPs the next year: Reds and Blues. One of the songs on Reds, "Who Are You, Really,” made its way to underground beatsmith Clams Casino, known mainly for his work with ASAP Rocky, Lil B and The Weeknd. -

IMPOSSIBLE LANDSCAPES (First Edit)

Delta Green Impossible Landscapes ©2020 The Delta Green Partnership IMPOSSIBLE LANDSCAPES A CAMPAIGN OF WONDER, HORROR, AND CONSPIRACY, FOR DELTA GREEN: THE ROLE-PLAYING GAME BY DENNIS DETWILLER ARC DREAM PUBLISHING PRESENTS DELTA GREEN: IMPOSSIBLE LANDSCAPES BY DENNIS DETWILLER DEVELOPERS & EDITORS DENNIS DETWILLER & SHANE IVEY ART DIRECTOR & ILLUSTRATOR DENNIS DETWILLER GRAPHIC DESIGNER SIMEON COGSWELL COPY EDITOR LISA PADOL DELTA GREEN CREATED BY DENNIS DETWILLER, ADAM SCOTT GLANCY & JOHN SCOTT TYNES All writing and art ©2019 Dennis Detwiller. “Is the darkness/Ours to take?/Bathed in lightness/Bathed in heat/All is well/As long as we keep spinning/Here and now/Dancing behind a wall/Hear the old songs/And laughter within/All forgiven/Always and never been true.” 1 Delta Green Impossible Landscapes ©2020 The Delta Green Partnership IMPOSSIBLE LANDSCAPES 1 THIS BOOK HAS TEETH… 19 INTRODUCTION 20 CAMPAIGN STRUCTURE 20 IN THE FIELD: TRANSIT BETWEEN OPERATIONS 20 OPERATIONAL SUMMARIES AND STRUCTURE 21 The Night Floors 21 A Volume of Secret Faces 21 Like a Map Made of Skin 21 The End of the World of the End 22 DISINFORMATION: MENTAL ILLNESS AND THE KING IN YELLOW 22 PART ONE: THE KING IN YELLOW 23 DISINFORMATION: CARCOSA, THE KING IN YELLOW, AND HASTUR 23 THE BOOK, THE NIGHT WORLD, AND CARCOSA 24 IN THE FIELD: THEMES OF THE KING IN YELLOW 24 DELTA GREEN AND THE KING IN YELLOW 25 THE FIRST KNOWN OUTBREAK OF LE ROI EN JAUNE (1895) 26 DISINFORMATION: TRUE ORIGINS 26 THE RED BOOK (1951) 26 OPERATION LUNA (1952) 27 DISINFORMATION: EMMET MOSEBY M.I.A. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Manhatta N Communi Ty B Oar

THE CITY OF NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533-5300 www.cb3manhattan.org - [email protected] , Board Chair Susan Stetzer, District Manager Community Board 3 Liquor License Application Questionnaire Please bring the following items to the meeting: NOTE: ALL ITEMS MUST BE SUBMITTED FOR APPLICATION TO BE CONSIDERED. Photographs of the inside and outside of the premise. Schematics, floor plans or architectural drawings of the inside of the premise. A proposed food and or drink menu. Petition in support of proposed business or change in business with signatures from residential tenants at location and in buildings adjacent to, across the street from and behind proposed location. Petition must give proposed hours and method of operation. For example: restaurant, sports bar, combination restaurant/bar. (petition provided) Notice of proposed business to block or tenant association if one exists. You can find community groups and contact information on the CB 3 website: http://www.nyc.gov/html/mancb3/html/communitygroups/community_group_listings.shtml Photographs of proof of conspicuous posting of meeting with newspaper showing date. If applicant has been or is licensed anywhere in City, letter from applicable community board indicating history of complaints and other comments. Check which you are applying for: new liquor license alteration of an existing liquor license corporate change Check if either of these apply: sale of assets upgrade (change of class) of an existing liquor license Today's Date: ______________________________________________________________________________________________4/21/2017, Amended on 5/25/2017 If applying for sale of assets, you must bring letter from current owner confirming that you are buying business or have the seller come with you to the meeting. -

HALLOWEEN NEW BROADWAY SHOWS CREEPY COCKTAILING Celebrate INPSIRED LOOKS

OCT 2017 OCT ® INPSIRED LOOKS Celebrate CREEPY COCKTAILING NEW BROADWAY SHOWS NEW BROADWAY HALLOWEEN NYC Monthly OCT2017 NYCMONTHLY.COM VOL. 7 NO.10 CONTENTS FEATURES INTERVIEWS BROADWAY SPECIAL FEATURE 36 Chicago 52 What to Fall for On Stage World-Class Hitmakers The Season's Lineup of New Shows Return to Coney Island 42 Brady Skjei LIVE ENTERTAINMENT Skating into His Second 32 Monster Mash Season with the Rangers A Frightfully Good Lineup of Live Music 50 Laurent Tourondel The Chef Chats About His DINING & DRINKS Quintet of NYC Restaurants 16 Creepy Cocktailing 62 Tricks and Treats, on the Rocks Anna Camp and Straight Bright Actress of Film & TV Returns to Broadway 46 National Pasta Month Twirl Through This Celebration at these Prime Pasta Joints 4 NYCMONTHLY.COM CONTENTS SHOPPING 20 Dapper Dress-Up Looks Inspired by Halloween Icons 28 Femme Fatales for Halloween Looks Inspired by Halloween Icons SPORTS 40 October Sports Calendar of Can't Miss Sporting Events MUSEUMS 64 Exhibit-Worthy Wears Three Fashion-Themed Shows Focus on the Natural World, Individual Style, and Iconic Looks IN EVERY ISSUE 12 NYCM Top 10 Things To Do in October ON THE COVER: 38 Live Entertainment Halloween Townhouse Photo by Shane J. Rosen-Gould Calendar Must-see Concerts in October While it may fall on the final day of the month, Halloween is certainly celebrated the other 30 days of October in New York 24 Fashion Editors' Picks City. Brownstone homes become cloaked in decorative cobwebs, Hand Chosen by Rue La La's local watering holes start mixing up seasonal potions, and haute Fashion Editors couture turns to haute costumes. -

Columbia Poetry Review Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Poetry Review Publications Spring 4-1-2002 Columbia Poetry Review Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Poetry Review" (2002). Columbia Poetry Review. 15. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Poetry Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLUMBIA poetry review 1 3 > no. 15 $6.00 USA $9.00 CANADA o 74470 82069 7 COLUMBIA POETRY REVIEW Columbia College Chicago Spring 2002 Columbia Poetry Review is published in the spring of each year by the English Department of Columbia College, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60605. Submissions are encouraged and should be sent to the above address from August 15 to January 1. Subscriptions and sample copies are available at $6.oo an issue in the U.S.; $9.00 in Canada and elsewhere. The magazine is edited by students in the un dergraduate poetry program and distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Periodicals. Copyright (c) 2002 by Columbia College. ISBN: 0-932026-59-1 Grateful acknowledgment is made to Garnett Kilberg-Cohen, Chair of the English Department; Dr. Cheryl Johnson-Odim, Dean of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Steven Kapelke, Provost; and Dr.