Clampdown: Pop-Cultural Wars on Class and Gender Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gavin Ames Avid Editor

Gavin Ames Avid Editor Profile Gavin is an exceptionally talented editor. Fast, creative, and very technically minded. He is one of the best music editors around, with vast live multi-cam experience ranging from The Isle of Wight Festival, to Take That, Faithless and Primal Scream concerts. Since excelling in the music genre, Gavin went on to develop his skills in comedy, editing Shooting Stars. His talents have since gone from strength to strength and he now has a wide range of high-end credits under his belt, such as live stand up for Bill Bailey, Steven Merchant, Ed Byrne and Angelos Epithemiou. He has also edited sketch comedy, a number of studio shows and comedy docs. Gavin has a real passion for editing comedy and clients love working with him so much that they ask him back time and time again! Comedy / Entertainment / Factual “The World According to Jeff Goldblum” Series 2. Through the prism of Jeff Goldblum's always inquisitive and highly entertaining mind, nothing is as it seem. Each episode is centred around something we all love — like sneakers or ice cream — as Jeff pulls the thread on these deceptively familiar objects and unravels a wonderful world of astonishing connections, fascinating science and history, amazing people, and a whole lot of surprising big ideas and insights. Nutopia for National Geographic and Disney + “Guessable” In this comedy game show, two celebrity teams compete to identify the famous name or object inside a mystery box. Sara Pascoe hosts the show with John Kearns on hand as her assistant. Alan Davies and Darren Harriott are the team captains, in a format that puts a twist on classic family games. -

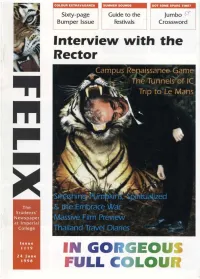

Felix Issue 1103, 1998

COLOUR EXTRAVAGANZA SUMMER SOUNDS GOT SOME SPARE TIME? Sixty-page Guide to the Jumbo $f Bumper Issue Festivals Crossword Interview with the Rector Campus Renaissance Game y the Tunnels "of IC 1 'I ^ Trip to Le Mans 7 ' W- & the Embrace War Massive Film Preview Thailand Travel Diaries IN GO EOUS FULL C 4 2 GAME 24 June 1998 24 June 1998 GAME 59 Automatic seating in Great Hall opens 1 9 18 unexpectedly during The Rector nicks your exam, killing fff parking space. Miss a go. Felix finds out that you bunged the builders to you're fc Rich old fo work Faster. "start small antiques shop. £2 million. Back one. ii : 1 1 John Foster electro- cutes himself while cutting IC Radio's JCR feed. Go »zzle all the Forward one. nove to the is. The End. P©r/-D®(aia@ You Bung folders to TTafeDts iMmk faster. 213 [?®0B[jafi®Drjfl 40 is (SoOOogj® gtssrjiBGariy tsm<s5xps@G(§tlI ITCD® esiDDorpo/Js Bs a DDD®<3CM?GII (SDB(Sorjaai„ (pAsasamG aracil f?QflrjTi@Gfi®OTjaD Y®E]'RS fifelaL rpDaecsS V®QO wafccs (MJDDD Haglfe G® sGairGo (SRBarjDDo GBa@to G® §GapG„ i You give the Sheffield building a face-lift, it still looks horrible. Conference Hey ho, miss a go. Office doesn't buy new flow furniture. ir failing Take an extra I. Move go. steps back. start Place one Infamou chunk of asbestos raer shopS<ee| player on this square, », roll a die, and try your Southsid luck at the CAMPUS £0.5 mil nuclear reactor ^ RENAISSANCE GAME ^ ill. -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

Radio 4 Listings for 1 – 7 February 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 01 FEBRUARY 2020 in the Digital Realm

Radio 4 Listings for 1 – 7 February 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 01 FEBRUARY 2020 in the digital realm. A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000drp6) When Alice's father was diagnosed with cancer, she found National and international news from BBC Radio 4 herself at a loss as to how to communicate with him digitally. SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000dxqp) One solution was sending more personal objects. But Alice George Parker of the Financial Times looks behind the scenes works in digital communication, and in this talk at the Shambala at Westminster. SAT 00:30 Motherwell (m000drp8) Festival she describes her journey to improve the tools available The UK has left the EU so what happens next? what is the Episode 5 to communicate grief and sadness. negotiating strength of the UK and what can we expect form the hard bargaining ahead? The late journalist Deborah Orr was born and bred in the Producer: Giles Edwards The editor is Marie Jessel Scottish steel town of Motherwell, in the west of Scotland. Growing up the product of a mixed marriage, with an English mother and a Scottish father, she was often a child on the edge SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000dxq9) SAT 11:30 From Our Own Correspondent (m000dxqr) of her working class community, a 'weird child', who found The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Insight, wit and analysis from BBC correspondents, journalists solace in books, nature and in her mother's company. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

Mima Press Release Coming up on the Evening of Saturday 27

mima Press Release 22 September 2014 mima live, Saturday 27 September 2014 – Monotony, Brown Brogues, Milky Wimpshake & Sorry Escalator Coming up on the evening of Saturday 27 September is the return of mima live, a free event which is a part of the town-wide Middlesbrough Live. With a line up which includes BBC Radio 6 Music darlings Monotony, alongside Brown Brogues, Milky Wimpshake & Sorry Escalator, this year’s event should be not one to miss. These bands have been handpicked by our mima Live curator Nicky Peacock as the best up and coming acts of this year – apart from Milky Wimpshake who have always been brilliant. Monotony is a four piece punk outfit from London and Brighton who are taking BBC Radio 6 Music by storm, getting daily plays on the Marc Riley show. Monotony is a side project of the garage racket band Sauna Youth in which they all switched instruments. Their glorious garage racket has caught the attention of Colin Newman of iconic post-punk band Wire, who cites them as his new favourite band. They are joined by Manchester’s Brown Brogues - two men making savage garage sounds with drums, guitar and primitive hollering. They wrestle, they swear and they spectacularly outshone indie superstars The Kills on a recent US tour - your mum wouldn't like them but we do. Next in the line-up is one of the UKs best loved indie pop bands Milky Wimpshake. Forever relevant, they continue to be purveyors of ‘love songs for punk rockers’. Fronted by Pete Dale, of the much-loved and legendary DIY label Slampt – he ruled the Newcastle scene for most of the ‘90s and introduced us to bands such as Kenickie (featuring broadcaster Lauren Laverne), Yummy Fur (featuring members of Franz Ferdinand) and Pussycat Trash. -

Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17

Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Annex to the BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport by command of Her Majesty © BBC Copyright 2017 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Photographs are used ©BBC or used under the terms of the PACT agreement except where otherwise identified. Permission from copyright holders must be sought before any photographs are reproduced. You can download this publication from bbc.co.uk/annualreport BBC Pay Disclosures July 2017 Report from the BBC Remuneration Committee of people paid more than £150,000 of licence fee revenue in the financial year 2016/17 1 Senior Executives Since 2009, we have disclosed salaries, expenses, gifts and hospitality for all senior managers in the BBC, who have a full time equivalent salary of £150,000 or more or who sit on a major divisional board. Under the terms of our new Charter, we are now required to publish an annual report for each financial year from the Remuneration Committee with the names of all senior executives of the BBC paid more than £150,000 from licence fee revenue in a financial year. These are set out in this document in bands of £50,000. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

BBC Radio International Features Catalogue Contents

BBC Radio International Features Catalogue BBC Radio International offers fascinating, thought provoking features that delve into a wide range of subjects, including factual, arts and culture, science and music, in a varied and entertaining way. Noted for their depth of research and authoritative presentation, BBC features give your listeners access to high profile presenters and contributors as they gain a captivating insight into the world around them. You can easily search the BBC features by clicking on the genre under contents. Take a look through the op- tions available and select from hundreds of hours of content spanning from present day back through the last ten years. Have a question or want to know more about a specific genre or programme? Contact: Larissa Abid, Ana Bastos or Laura Lawrence for more details Contents New this month – September 2021 ...........................................................................................................................1 Factual .......................................................................................................................................................................4 Arts and Culture .......................................................................................................................................................26 Music .......................................................................................................................................................................52 Science ....................................................................................................................................................................75 -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People.. -

Wk 44 – 1994 Oct 29 – UK Top 75

Wk 44 – 1994 Oct 29 – UK Top 75 1 2 5 BABY COME BACK Pato Banton 2 3 7 SATURDAY NIGHT Whigfield 3 4 6 ALWAYS Bon Jovi 4 1 3 SURE Take That 5 6 6 SWEETNESS Michelle Gayle 6 10 2 SHE'S GOT THAT VIBE R. Kelly 7 5 7 GIRLS JUST WANT TO HAVE FUN Cyndi Lauper 8 9 7 WELCOME TO TOMORROW Snap ft Summer 9 - 1 WHEN WE DANCE Sting 10 8 9 STAY Lisa Loeb And Nine Stories 11 15 2 SEVENTEEN Let Loose 12 7 2 CIGARETTES AND ALCOHOL Oasis 13 13 4 CIRCLE OF LIFE Elton John 14 11 8 THE RHYTHM OF THE NIGHT Corona 15 31 2 THE STRANGEST PARTY INXS 16 - 1 YOU NEVER LOVE THE SAME WAY TWICE Rozalla 17 20 2 SOME GIRLS Ultimate Kaos 18 12 4 SECRET Madonna 19 - 1 STARS China Black 20 - 1 WELCOME TO PARADISE Green Day 21 - 1 YOU CAN GET IT Maxx 22 16 3 MOVE IT UP Cappella 23 14 5 STEWAM East 17 24 - 1 SLY Massive Attack 25 21 3 TURN THE BEAT AROUND Gloria Estefan 26 - 1 HIGH HOPES Pink Floyd 27 - 1 ALICE WHAT'S THE MATTER Terrorvision 28 18 4 IF I GIVE YOU MY NUMBER PJ & Duncan 29 17 2 CONNECTION Elastica 30 - 1 FEELING SO REAL Moby 31 19 4 BEST OF MY LOVE CJ Lewis 32 22 7 ENDLESS LOVE Luther Vandross And Mariah Carey 33 25 9 I'LL MAKE LOVE TO YOU Boyz II Men 34 23 2 TURN UP THE POWER N-Trance 35 29 5 ZOMBIE Cranberries 36 24 4 I WANT THE WORLD 2wo Third3 37 27 3 VIVA LA MEGABABES Shampoo 38 - 1 WHEN DO I GET TO SING MY WAY Sparks 39 35 24 LOVE IS ALL AROUND Wet Wet Wet 40 30 3 PUSH THE FEELING ON Nightcrawlers 41 45 2 TAKE ME HOME Joe Cocker And Bekka Bramlett 42 53 2 THINK TWICE Celine Dion 43 - 1 CAUGHT BY THE FUZZ Supergrass 44 26 2 PLANET CARAVAN Pantera 45 34 -

Read Book Sugar Sporties Kindle

SUGAR SPORTIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paula MacLeod | 48 pages | 24 Aug 2012 | Search Press Ltd | 9781844488209 | English | Tunbridge Wells, United Kingdom Sporty Spice - CHIC AND SUGAR My husband and I are interested in learning about beekeeping he's even scoped out our backyard for the likely spot to place a hive. I've also heard that honey is a natural antiseptic and good for whatever ails your skin. Keeping bees is great - we have a hive, though my husband does the scary bit! The Slovenian bees are a bit more chilled than ours bit like the people! Notify me of follow-up comments by email. Notify me of new posts by email. Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. Email Address. Honey vs. Oct 26, Patricia Carswell. Sell general listings with no success fees, plus more exclusive benefits with Choice by Trade Me. Current subscription listings:. Listings this month:. Monthly plan:. Prepaid listings remaining:. Prepaid branding remaining:. Prepaid features remaining:. Prepaid promoted listings remaining:. Buy a job pack. Whether you have sold your item on Trade Me, or have something else you need to send, you can use our 'Book a courier' service. Search expired listings. View category directory. List a General item List for free - only pay when it sells. Other vehicle Motorbikes, boats, caravans and more. Sell and save on fees Sell general listings with no success fees, plus more exclusive benefits with Choice by Trade Me. View My Trade Me. Reporting Monthly summary Export agent reports Export job reports Current subscription listings: Listings this month: Monthly plan: Prepaid listings remaining: Prepaid branding remaining: Prepaid features remaining: Prepaid promoted listings remaining: Buy a job pack.