DOUGLAS A. MUNRO a World War II Hero from Cle Elum by C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2016 Newsletter

Freedom’s Voice The Monthly Newsletter of the Military History Center 112 N. Main ST Broken Arrow, OK 74012 http://www.okmhc.org/ “Promoting Patriotism through the Preservation of Military History” Volume 4, Number 8 August 2016 United States Armed Services August MHC Events Day of Observance August was a busy month for the Military History Center. Two important patriotic events were held at the Museum and a Coast Guard Birthday – August 4 fundraiser, Military Trivia Evening, was held at the Armed Forc- es Reserve Center in Broken Arrow. On Saturday, August 6, the MHC hosted Purple Heart Recognition Day. Because of a morning rainstorm, the event was held inside the Museum rather than on the Flag Plaza as planned. Even with the rain, about 125 or so local patriots at- tended the event, including a large contingent of Union High School ROTC cadets. The Ernest Childers Chapter of the Military Order of the Purple Heart presented the event. Ms. Elaine Childers, daugh- ter of Medal of Honor and Purple Heart Recipient, Lt. Col. Ern- est Childers was the special guest. The ninth annual Wagoner County Coweta Mission Civil War Weekend will be held on October 28-30 at the farm of Mr. Arthur Street, located southeast of Coweta. Mr. Street is a Civil War reenactor and an expert on Civil War Era Artillery. This is an event you won’t want to miss. So, mark your cal- endars now. The September newsletter will contain detailed information about the event. All net proceeds from the Civil War Weekend are for the benefit of the MHC. -

Gudalcanal American Memorial

ENGLISH American Battle Monuments Commission This agency of the United States government operates and AMERICAN BATTLE MONUMENTS COMMISSION maintains 26 American cemeteries and 30 memorials, monuments and markers in 17 countries. The Commission works to fulfill the vision of its first chairman, General of the Armies John J. Pershing. Guadalcanal American Memorial Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I, promised that “time will not dim the glory of their deeds.” Guadalcanal American Memorial GPS S9 26.554 E159 57.441 The Guadalcanal American Memorial stands on Skyline Ridge overlooking the town of Honiara and the Matanikau River. American Battle Monuments Commission 2300 Clarendon Boulevard Suite 500 Arlington, VA 22201 USA Guadalcanal American Manila American Cemetery Memorial McKinley Road Skyline Ridge Global City, Taguig P.O. Box 1194 Republic of Philippines Honiara, Solomon Islands tel 011-632-844-0212 email [email protected] tel 011-677-23426 gps N14 32.483 E121 03.008 For more information on this site and other ABMC commemorative sites, please visit ‘Time will not dim the glory of their deeds.’ www.abmc.gov - General of the Armies John J. Pershing January 2019 Guadalcanal American Memorial Marine artillerymen The Guadalcanal American operate from a Japanese field gun Memorial honors those emplacement captured American and Allied servicemen early in the Guadalcanal who lost their lives during the campaign. Photo: The National Archives Guadalcanal campaign of World War II. The memorial consists of AUGUST 8: Marine units occupied the Japanese airdrome at Lunga. It an inscribed central pylon four Photo: ABMC was later named Henderson Field. -

164Th Infantry News: September 1998

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons 164th Infantry Regiment Publications 9-1998 164th Infantry News: September 1998 164th Infantry Association Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation 164th Infantry Association, "164th Infantry News: September 1998" (1998). 164th Infantry Regiment Publications. 55. https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in 164th Infantry Regiment Publications by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE 164TH INFANTRY NEWS Vot 38 · N o, 6 Sepitemlber 1, 1998 Guadalcanal (Excerpts taken from the book Orchids In The Mud: Edited by Robert C. Muehrcke) Orch id s In The Mud, the record of the 132nd Infan try Regiment, edited by Robert C. Mueherke. GUADALCANAL AND T H E SOLOMON ISLANDS The Solomon Archipelago named after the King of Kings, lie in the Pacific Ocean between longitude 154 and 163 east, and between latitude 5 and 12 south. It is due east of Papua, New Guinea, northeast of Australia and northwest of the tri angle formed by Fiji, New Caledonia, and the New Hebrides. The Solomon Islands are a parallel chain of coral capped isles extending for 600 miles. Each row of islands is separated from the other by a wide, long passage named in World War II "The Slot." Geologically these islands are described as old coral deposits lying on an underwater mountain range, whi ch was th rust above the surface by long past volcanic actions. -

Douglas A. Munro Coast Guard Headquarters Building

113TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 1st Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 113–153 DOUGLAS A. MUNRO COAST GUARD HEADQUARTERS BUILDING JULY 16, 2013.—Referred to the House Calendar and ordered to be printed Mr. SHUSTER, from the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, submitted the following R E P O R T [To accompany H.R. 2611] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. 2611) to designate the headquarters building of the Coast Guard on the campus located at 2701 Martin Luther King, Jr., Avenue Southeast in the District of Columbia as the ‘‘Douglas A. Munro Coast Guard Headquarters Building’’, and for other purposes, having considered the same, report favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the bill do pass. CONTENTS Page Purpose of Legislation ............................................................................................. 2 Background and Need for Legislation .................................................................... 2 Hearings ................................................................................................................... 2 Legislative History and Consideration .................................................................. 2 Committee Votes ...................................................................................................... 2 Committee Oversight Findings ............................................................................... 3 New Budget Authority -

The Cost of the Navy's New Frigate

OCTOBER 2020 The Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate On April 30, 2020, the Navy awarded Fincantieri Several factors support the Navy’s estimate: Marinette Marine a contract to build the Navy’s new sur- face combatant, a guided missile frigate long designated • The FFG(X) is based on a design that has been in as FFG(X).1 The contract guarantees that Fincantieri will production for many years. build the lead ship (the first ship designed for a class) and gives the Navy options to build as many as nine addi- • Little if any new technology is being developed for it. tional ships. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office examines the potential costs if the Navy exercises • The contractor is an experienced builder of small all of those options. surface combatants. • CBO estimates the cost of the 10 FFG(X) ships • An independent estimate within the Department of would be $12.3 billion in 2020 (inflation-adjusted) Defense (DoD) was lower than the Navy’s estimate. dollars, about $1.2 billion per ship, on the basis of its own weight-based cost model. That amount is Other factors suggest the Navy’s estimate is too low: 40 percent more than the Navy’s estimate. • The costs of all surface combatants since 1970, as • The Navy estimates that the 10 ships would measured per thousand tons, were higher. cost $8.7 billion in 2020 dollars, an average of $870 million per ship. • Historically the Navy has almost always underestimated the cost of the lead ship, and a more • If the Navy’s estimate turns out to be accurate, expensive lead ship generally results in higher costs the FFG(X) would be the least expensive surface for the follow-on ships. -

Worldwide Equipment Guide Chapter 1: Littoral Systems

Dec 2016 Worldwide Equipment Guide Chapter 1: Littoral Systems TRADOC G-2 ACE Threats Integration Ft. Leavenworth, KS Distribution Statement: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Worldwide Equipment Guide Chapter 1: Littoral This chapter focuses on vessels for use in littoral ("near the shore") operations. Littoral activities include the following: - "brown water" naval operations in coastal waters (out to as far as 200+ km from shore), - amphibious landing operations or port entry (opposed and unopposed), - coastal defense actions (including patrols, engaging enemy, and denying entry) - operations in inland waterways (rivers, lakes, etc), and - actions in large marshy or swampy areas. There is no set distance for “brown water.” Littoral range is highly dependent on specific geography at any point along a coast. Littoral operations can be highly risky. Forces moving in water are often challenged by nature and must move at a slow pace while exposed to enemy observation and fires. Thus littoral forces will employ equipment best suited for well-planned operations with speed, coordination, and combined arms support. Littoral forces will employ a mix of conventional forces, specialized (naval, air, and ground) forces and equipment, and civilian equipment which can be acquired or recruited for the effort. Each type of action may require a different mix of equipment to deal with challenges of terrain, vulnerability, and enemy capabilities. Coastal water operations can utilize naval vessels that can operate in blue water. Naval battle groups for deep water also operate in littoral waters. Submarines and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) systems conduct missions in littoral waters. But challenges of shallow waters and shoreline threats also require use of smaller fast-attack boats, patrol craft, cutters, etc. -

Manila American Cemetery and Memorial

Manila American Cemetery and Memorial American Battle Monuments Commission - 1 - - 2 - - 3 - LOCATION The Manila American Cemetery is located about six miles southeast of the center of the city of Manila, Republic of the Philippines, within the limits of the former U.S. Army reservation of Fort William McKinley, now Fort Bonifacio. It can be reached most easily from the city by taxicab or other automobile via Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (Highway 54) and McKinley Road. The Nichols Field Road connects the Manila International Airport with the cemetery. HOURS The cemetery is open daily to the public from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm except December 25 and January 1. It is open on host country holidays. When the cemetery is open to the public, a staff member is on duty in the Visitors' Building to answer questions and escort relatives to grave and memorial sites. HISTORY Several months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, a strategic policy was adopted with respect to the United States priority of effort, should it be forced into war against the Axis powers (Germany and Italy) and simultaneously find itself at war with Japan. The policy was that the stronger European enemy would be defeated first. - 4 - With the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and the bombing attacks on 8 December on Wake Island, Guam, Hong Kong, Singapore and the Philippine Islands, the United States found itself thrust into a global war. (History records the other attacks as occurring on 8 December because of the International Date Line. -

Uses L06 2012 INDEX

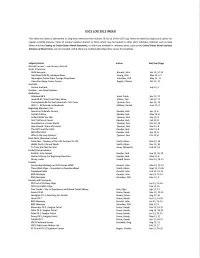

uses L06 2012 INDEX This Index lists items of permanent or long-term reference from Volume 79, #I-12 of the USCS Log. Items are listed by subject and author for regular monthly features. Items of merely transient interest or those which may be located in other USCS reference material, such as Data Sheets and the Catalog of United States Naval Postmarks, or which are available in reference texts, such as the United States Nuval Institute Almanuc of Naval Facts, are not included. USS & USCG are omitted with ship/cutter names for simplicity. Subject/Article Author Mo/Year/Page Aircraft Carriers -see Carriers, Aircraft Arctic / Antarctic RMS Nascopie Burnett, John Jan 12, 12-14 Northland (USCG); Hooligan News Young, John May 12, 6-7 Norwegian Cruise Ships; Foreign Navy News Schreiber, Phil May 12, 15 Operation Deep Freeze Covers Bogart, Charles Oct 12, 17 Australia Aurora Australis July 12, 5 Aviation - see Naval Aviation Battleships Alabama BB 8 Hoak, Frank Apr 12, 27 Iowa BB 61; West Coast Navy News Minter, Ted Feb 12, 11 Pennsylvania BB 38; Herb Rommel's First Cover Tjossem, Don Apr 12, 19 WW II - BB Gun Barrel Bookends Milliner, Darrell June 12, 9 Beginning Members, For American Philatelic Society Rawlins, Bob Jan 12, 8 Cachet Artistry Rawlins, Bob May 12, 8 Collect What You Like Tjossem, Don Sep 12, 8 Don't Write on Covers Rawlins, Bob Feb 12, 8 How Much is a Cover Worth Tjossem, Don Dec 12.10 How Should I Store My Covers Tjossem, Don Nov 12, 8 The USPS and the USCS Rawlins, Bob Mar 12, 8 WESTPEX 2012 Rawlins, Bob Apr 12, 8 What is the Locy System? Tjossem, Don Oct I2, 8 Book Deck; (Reviewer Listed) Fatal Dive - Mystery of the USS Grunion SS 216 Smith, Glenn Nov 12, 26 HMAS Perth, Life and Death Smith, Glenn Dec 12, 26 To Train the Fleet for War Jones, Richard D. -

US Navy and Coast Guard Vessels, Sunk Or Damaged Beyond

Casualties: U.S. Navy and Coast Guard Vessels, Sunk or Damaged Beyond Repair during World War II, 7 December 1941-1 October 1945 U.S. Navy Warships Mine Warfare Ships Patrol Ships Amphibious Ships Auxiliaries District Craft U.S. Coast Guard Ships Bibliography U.S. Navy Warships Battleship (BB) USS Arizona (BB-39) destroyed by Japanese aircraft bombs at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, 7 December 1941, and stricken from the Navy List, 1 December 1942. USS Oklahoma (BB-37) capsized and sank after being torpedoed by Japanese aircraft at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, 7 December 1941. Aircraft Carrier (CV) USS Hornet (CV-8) sunk after being torpedoed by Japanese aircraft during the Battle of Santa Cruz, Solomon Islands, 26 October 1942. USS Lexington (CV-2) sunk after being torpedoed by Japanese aircraft during the Battle of the Coral Sea, 8 May 1942. USS Wasp (CV-7) sunk after being torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-19 south of Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, 15 September 1942. USS Yorktown (CV-5) damaged by aircraft bombs on 4 June 1942 during the Battle of Midway and sunk after being torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-168, 7 June 1942. Aircraft Carrier, Small (CVL) USS Princeton (CVL-23) sunk after being bombed by Japanese aircraft during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Philippine Islands, 24 October 1944. Aircraft Carrier, Escort (CVE) USS Bismarck Sea (CVE-95) sunk by Kamikaze aircraft off Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, 21 February 1945. USS Block Island (CVE-21) sunk after being torpedoed by German submarine U-549 northwest of the Canary Islands, 29 May 1944. -

Douglas Munro at Guadalcanal

U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office Preserving Our History For Future Generations DOUGLAS MUNRO AT GUADALCANAL by Dr. Robert M. Browning Jr. "Douglas A. Munro Covers the Withdrawal of the 7th Marines at Guadalcanal." Artist: Bernard D'Andrea The Coast Guard's first major participation in the Pacific war was at Guadalcanal. Here the service played a large part in the landings on the islands. So critical was their task that they were later involved in every major amphibious campaign during World War II. During the war, the Coast Guard manned over 350 ships and hundreds more amphibious type assault craft. It was in these ships and craft that the Coast Guard fulfilled one of its most important but least glamorous roles during the war--that is getting the men to the beaches. The initial landings were made on Guadalcanal in August 1942, and this hard-fought campaign lasted for nearly six months. Seven weeks after the initial landings, during a small engagement near the Matanikau River, Signalman First Class Douglas Albert Munro, died while rescuing a group of marines near the Matanikau River. Posthumously awarded a Medal of Honor, he lived up to the Coast Guard's motto--"Semper Paratus." Douglas Munro grew up in the small town of Cle Elum, Washington. Enlisting in September 1939, Munro volunteered for duty on board the USCG cutter Spencer where he served until 1941. While on board he earned his Signalman 3rd Class rating. In June, President Roosevelt directed the Coast Guard to man four large transports and Page 1 of 5 U.S. -

WW2 – Guadalcanal Campaign

Guadalcanal 1942-43 COL Mark D. Harris 5 Dec 2013 Objectives • Learn about the Guadalcanal campaign. • Identify and discuss good and poor decisions and actions made by both sides during the campaign. • Draw parallels between their experience and modern military experience, especially military medicine. • Teach others the lessons learned. Strategic Situation - Allied • “Germany first” policy – 70% of US resources were against Germany, only 30% against Japan. • US did not have land, sea or air parity with Japan but was getting close to it. • US needed to support Australia because they were in danger and because Australia provided a bulwark against Japan in the Pacific. • Coast watchers in the Solomon Islands provided early notice of Japanese sea and air movements. Axis Division of the World (as considered in January 1942) Strategic Situation - Japanese • Recently lost four carriers at the Battle of Midway, their first major setback of the war. • Goal was to capture the major allied base at Port Moresby in New Guinea, thereby threatening Australia. • IJN wanted to occupy Guadalcanal to interdict US delivery of troops and supplies from Hawaii to Australia. • IJA wanted to concentrate forces for Port Moresby operation. Battle for Port Moresby 1942 Kokoda Track Operational Situation - Guadalcanal • Island in the Solomon chain 90 miles long and 25 miles wide. • No natural harbors, and south coast covered by coral reefs so only approach by sea is from the north. • Topography – mountains to 8000 feet, dormant volcanos, steep ravines, deep streams, and jungle. • Public Health threats – malaria, dengue, fungal, heat injury. • British protectorate since 1893 – Natives generally expected to be friendly. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 159, Pt. 8 July 16

July 16, 2013 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 159, Pt. 8 11493 Mr. NOLAN. Mr. Speaker, first I’d General aviation fosters a robust the Fort Myers airport, over the beautiful like to thank Representative POMPEO workforce of engineers, manufacturers, beaches and the big blue Gulf—can appre- for sponsoring this important legisla- maintenance professionals, and pilots, ciate why so many retired Air Force and airline tion. And of course, thanks to our and it is within the FAA’s power to en- pilots move to Florida and continue to take to Chairman SHUSTER and Ranking Mem- sure the success and sustainability of the skies. ber RAHALL and to both my Democratic this important industry. They can do Unfortunately, the burdens placed on small and Republican colleagues on the com- this by modernizing the regulatory re- aircraft manufacturers and owners stop them mittee for bringing this Small Aircraft quirements to improve safety, decrease from enjoying flying. When government bu- Revitalization Act to the floor of the cost, and set new standards for compli- reaucrats become more focused on their own Congress in such an expeditious and bi- ance in testing, just as H.R. 1848 re- job security than the safety of pilots, it is time partisan manner. quires. for a change. This important legislation will Mr. Speaker, by streamlining and Mr. Speaker, I’m a small business- save pilots money and time while ensuring modernizing the rules and regulations man. I can tell you this is good for safety in our skies and it deserves your sup- that govern our small aircraft indus- jobs, it’s good for the economy, and, port.