INDO 99 0 1433277178 51 66.Pdf (433.2Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bab Iii Biografi Teuku Umar

BAB III BIOGRAFI TEUKU UMAR A. Kelahiran dan Masa Muda Teuku Umar Teuku Umar Johan Pahlawan lahir pada tahun 1854 M di Meulaboh, tepatnya di Gampong Masjid, sekarang Gampong Belakang, Kecamatan Johan Pahlawan. Ia dilahirkan dari seorang ayah yang bernama Teuku Tjut Mahmud dan ibu Tjut Mohani di mana pasangan ini dikarunia empat anak yaitu Teuku Musa, Tjut Intan, Teuku Umar dan Teuku Mansur.75 Teuku Umar seorang Aceh dan memiliki silsilah dengan Teuku Laksamana Muda Nanta, seorang Laksamana Aceh yang ditugaskan oleh Sultan Iskandar Muda pada tahun 1635 M sebagai Panglima Angkatan Perang Aceh di Andalas Barat dan sekaligus ditunjuk menjadi Gubernur Militer Aceh di Tanah Minang.76 Ayahnya, Teuku Achmad Mahmud, adalah seorang uleebalang (kepala daerah). Sementara ibundanya berasal dari lingkungan istana kerajaan di Meulaboh. Dalam buku Ensiklopedi Pahlawan Nasional yang disusun Julinar Said dan kawan-kawan (1995) disebutkan, dari garis ayahnya, Teuku Umar berdarah Minangkabau.77 Antara keluarga Teuku Umar dengan tanah rencong memang terikat terjalin kedekatan sejak dulu. Umar keturunan Datuk Makhudum Sati orang kepercayaan Sultan Iskandar Muda (1607-1636 M), yang diberi wewenang untuk memimpin wilayah Pariaman di Sumatera Barat sebagai bagian dari Kesultanan Aceh kala itu.78 Pada Tahun 1800 M, anak keturunan Teuku Laksamana Muda Nanta mendapatkan tekanan dari kaum ulama di tanah Andalas sehingga menyebabkan 75Ria Listina, Biografi Pahlawan Kusuma Bangsa, ( Jakarta: PT. Sarana Bangun Pustaka, 2010), hlm.22 76Ibid, hlm. 24 77Ragil Suwarna Pragolapati, Cut Nya Dien, Volume 1, 1982, hlm. 14 78Ibid, hlm. 21 40 mereka kembali ke Aceh lewat jalur laut sebelah barat dan kemudian mereka mendarat di Meulaboh di mana salah satu pemimpin rombongan tersebut bernama Machdum Sakti Yang Bergelar Teuku Nanta Teulenbeh yang kemudian diangkat oleh Sultan Aceh sebagai penjaga Taman Sultan di Kutaraja.79 Teuku Umar yang membangkitkan semangat perlawanan terhadap Belanda. -

National Heroes in Indonesian History Text Book

Paramita:Paramita: Historical Historical Studies Studies Journal, Journal, 29(2) 29(2) 2019: 2019 119 -129 ISSN: 0854-0039, E-ISSN: 2407-5825 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15294/paramita.v29i2.16217 NATIONAL HEROES IN INDONESIAN HISTORY TEXT BOOK Suwito Eko Pramono, Tsabit Azinar Ahmad, Putri Agus Wijayati Department of History, Faculty of Social Sciences, Universitas Negeri Semarang ABSTRACT ABSTRAK History education has an essential role in Pendidikan sejarah memiliki peran penting building the character of society. One of the dalam membangun karakter masyarakat. Sa- advantages of learning history in terms of val- lah satu keuntungan dari belajar sejarah dalam ue inculcation is the existence of a hero who is hal penanaman nilai adalah keberadaan pahla- made a role model. Historical figures become wan yang dijadikan panutan. Tokoh sejarah best practices in the internalization of values. menjadi praktik terbaik dalam internalisasi However, the study of heroism and efforts to nilai. Namun, studi tentang kepahlawanan instill it in history learning has not been done dan upaya menanamkannya dalam pembelaja- much. Therefore, researchers are interested in ran sejarah belum banyak dilakukan. Oleh reviewing the values of bravery and internali- karena itu, peneliti tertarik untuk meninjau zation in education. Through textbook studies nilai-nilai keberanian dan internalisasi dalam and curriculum analysis, researchers can col- pendidikan. Melalui studi buku teks dan ana- lect data about national heroes in the context lisis kurikulum, peneliti dapat mengumpulkan of learning. The results showed that not all data tentang pahlawan nasional dalam national heroes were included in textbooks. konteks pembelajaran. Hasil penelitian Besides, not all the heroes mentioned in the menunjukkan bahwa tidak semua pahlawan book are specifically reviewed. -

IJISRT19OCT2005 by Ijisrt19oct2005 Ijisrt19oct2005

IJISRT19OCT2005 by Ijisrt19oct2005 Ijisrt19oct2005 Submission date: 21-Oct-2019 12:49PM (UTC+0530) Submission ID: 1197076621 File name: 1571641883.docx (79.32K) Word count: 6461 Character count: 35442 IJISRT19OCT2005 ORIGINALITY REPORT 44% 25% 18% 41% SIMILARITY INDEX INTERNET SOURCES PUBLICATIONS STUDENT PAPERS PRIMARY SOURCES Submitted to Binus University International 1 Student Paper 2% Submitted to IMI University Centre 2 Student Paper 2% Submitted to Sriwijaya University 3 Student Paper 2% www.emeraldinsight.com 4 Internet Source 2% Submitted to Higher Education Commission 5 % Pakistan 2 Student Paper Submitted to University of Wales Institute, 6 % Cardiff 1 Student Paper Submitted to Universiti Teknologi MARA 7 Student Paper 1% www.um.edu.mt 8 Internet Source 1% Submitted to Universitas Warmadewa 9 Student Paper 1% Submitted to Strayer University 10 Student Paper 1% Submitted to Polytechnic of Namibia 11 Student Paper 1% www.mcser.org 12 Internet Source 1% Submitted to President University 13 Student Paper 1% www.iosrjournals.org 14 Internet Source 1% Submitted to The Chicago School of 15 % Professional Psychology 1 Student Paper pdfs.semanticscholar.org 16 Internet Source 1% Submitted to Universitas Riau 17 Student Paper 1% Submitted to University of Greenwich 18 Student Paper 1% Submitted to University of Northumbria at 19 % Newcastle 1 Student Paper www.todayscience.org 20 Internet Source 1% www.gbmrjournal.com 21 Internet Source 1% journals.sagepub.com 22 Internet Source 1% mucc.mahidol.ac.th 23 Internet Source 1% ijibm.elitehall.com 24 Internet Source <1% www.ijeronline.com 25 Internet Source <1% Submitted to University of Northampton 26 Student Paper <1% aimos.ugm.ac.id 27 Internet Source <1% www.i-scholar.in 28 Internet Source <1% Submitted to Jabatan Pendidikan Politeknik Dan 29 % Kolej Komuniti <1 Student Paper Submitted to 82915 30 Student Paper <1% Submitted to Universitas Terbuka 31 Student Paper <1% Anik Anekawati, Bambang Widjanarko Otok, 32 % Purhadi, Sutikno. -

Vol. 9, No. 1, January 2021

Vol. 9, No. 1, January 2021 JURNAL ILMIAH PEURADEUN The International Journal of Social Sciences p-ISSN: 2338-8617/ e-ISSN: 2443-2067 www.journal.scadindependent.org Vol. 9, No. 1, January 2021 Pages: 179-188 The Analysis of Student Character Values in the Use of Secondary Metabolic Utilization Lab Module Nurhafidhah1; Hasby2; Sirry Alvina3 1,2 Department of chemical Education Studies, Samudra University, Indonesia 3 Department of chemical Education Studies, Malikussaleh University, Indonesia Article in Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun Available at : https://journal.scadindependent.org/index.php/jipeuradeun/article/view/484 DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.26811/peuradeun.v9i1.484 How to Cite this Article APA : Nurhafidhah, N., Hasby, H., & Alvina, S. (2021). The Analysis of Student Character Values in the Use of Secondary Metabolic Utilization Lab Module. Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun, 9(1), 179-188. doi:10.26811/peuradeun.v9i1.484 Others Visit : https://journal.scadindependent.org/index.php/jipeuradeun/article/view/484 Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun, the International Journal of Social Sciences, is a leading peer-reviewed and open-access journal, which publishes scholarly work, and specializes in the Social Sciences, consolidates fundamental and applied research activities with a very wide ranging coverage. This can include studies and reviews conducted by multidisciplinary teams, as well as research that evaluates or reports on the results of scientific teams. JIP published 3 times of year (January, May, and September) with p-ISSN: 2338-8617 and e-ISSN: 2443-2067. Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun has become a CrossRef Member. Therefore, all articles published will have unique DOI number, and JIP also has been accredited by the Ministry of Research Technology and Higher Education Republic of Indonesia (SK Dirjen PRP RistekDikti No. -

Organizational Commitment As an Intervening Variable

Indonesian Journal of Educational Review Available online at p-ISSN 2338-2018 | e-ISSN 2335-8407 http://pps.unj.ac.id/journal/ijer Vol. 5, No.2 , Desember 2018, p 39-48 ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT AS AN INTERVENING VARIABLE, THE INFLUENCE OF THE JOB SATISFACTION, ORGANIZATIONAL CITIZENSHIP BEHAVIOR, QUALITY OF WORK LIFE , AGAINST THE EMPLOYEE PERFORMANCE : A CASE STUDY : IN THE REGIONAL PUBLIC SERVICE WOMEN'S AND CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL OF ACEH PROVINCE. Ahadi Arifin1, Ibrahim Qomarius2, Sullaida3, Nurmala4, Yenny Novita5 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] State Malikussaleh University Abstract This aim of this study the organizational commitment as an intervening variable, the influence of the job satisfaction, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Quality of Work Life, against the employee performance : Case Study : In The Regional Public Service Women's and Children's Hospital of Aceh Province . The research population is all employees of 254 people, and total sample of 156. The data analysis method used is Structural Equation Modelling. The results showed Organizational Commitment able to mediated the affect of the job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior and quality of work life against the employee performance is partially. And the relationship the job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior and quality of work life have a significant of relationship on the organizational commitment and employee performance. Keywords : Job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, quality of work life, organizational commitment, employee performance Women’s and Children’s Hospital of Aceh Province is an organization owned by the local government of Aceh that serves to provide health services to improve public health status. -

Research Study

*. APPROVED FOR RELEASE DATE:.( mY 2007 I, Research Study liWOlVEXZ4-1965 neCoup That Batkfired December 1968- i i ! This publication is prepared for tbe w of US. Cavernmeat officials. The formaf coverage urd contents of tbe puti+tim are designed to meet the specific requirements of those u~n.US. Covernment offids may obtain additional copies of this document directly or through liaison hl from the Cend InteIIigencx Agency. Non-US. Government usem myobtain this dong with rimikr CIA publications on a subscription bask by addressing inquiries to: Document Expediting (DOCEX) bject Exchange and Gift Division Library of Con- Washington, D.C ZOSaO Non-US. Gowrrrmmt users not interested in the DOCEX Project subscription service may purchase xeproductio~~of rpecific publications on nn individual hasis from: Photoduplication Servia Libmy of Congress W~hington,D.C. 20540 f ? INDONESIA - 1965 The Coup That Backfired December 1968 BURY& LAOS TMAILANO CAYBODIA SOUTU VICINAY PHILIPPIIEL b. .- .r4.n MALAYSIA INDONESIA . .. .. 4. , 1. AUSTRALIA JAVA Foreword What is commonly referred to as the Indonesian coup is more properly called "The 30 September Movement," the name the conspirators themselves gave their movement. In this paper, the term "Indonesian coup" is used inter- changeably with "The 30 September Movement ," mainly for the sake of variety. It is technically correct to refer to the events in lndonesia as a "coup" in the literal sense of the word, meaning "a sudden, forceful stroke in politics." To the extent that the word has been accepted in common usage to mean "the sudden and forcible overthrow - of the government ," however, it may be misleading. -

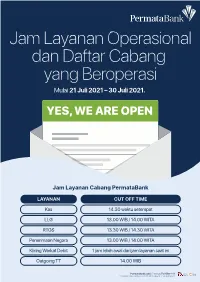

Update Daftar Cabang Yang B

Jam Layanan Operasional dan Daftar Cabang yang Beroperasi Mulai 21 Juli 2021 – 30 Juli 2021. YES, WE ARE OPEN Jam Layanan Cabang PermataBank LAYANAN CUT OFF TIME Kas 14.30 waktu setempat LLG 13.00 WIB / 14.00 WITA RTGS 13.30 WIB / 14.30 WITA Penerimaan Negara 13.00 WIB / 14.00 WITA Kliring Warkat Debit 1 jam lebih awal dari jam layanan saat ini Outgoing TT 14.00 WIB PermataBank.com | PermataTel 1500-111 PermataBank terdaftar dan diawasi oleh OJK dan merupakan peserta penjaminan LPS Jakarta Pusat Harmoni Jakarta Pangeran Jayakarta Jakarta Menara Astra Jakarta Plaza Index Jakarta Menara Batavia Jakarta Rukan Cempaka Putih Permai Jakarta Menteng Gondangdia Jakarta Sawah Besar Jakarta Mid Plaza Jakarta Jakarta Barat Citra Garden 1 Jakarta Puri Indah Jakarta Grand Puri Niaga Jakarta Taman Duta Mas Jakarta Hayam Wuruk Jakarta Taman Palem Jakarta Intercon Kebun Jeruk Jakarta Taman Ratu Jakarta Mangga Besar Jakarta Wisma AKR Jakarta Jakarta Selatan ACC Fatmawati Jakarta Menara FIF Jakarta ACC Simatupang Jakarta Menara Kadin Jakarta Atrium Jakarta Metro Pondok Indah Jakarta BEJ Tower II Jakarta Prudential Tower Jakarta Kasablanka Jakarta Sudirman Jakarta KCPS Tebet Soepomo Office Park Tebet Supomo Jakarta KCS Arteri Pondok Indah Wisma Surya Kemang Jakarta Melawai Jakarta Jakarta Timur Astra Agro Lestari Jakarta Kalimalang Pangkalan Jati Jakarta Jatinegara Jakarta Wisma Arion Jakarta PermataBank.com | PermataTel 1500-111 PermataBank terdaftar dan diawasi oleh OJK dan merupakan peserta penjaminan LPS Jakarta Utara Kelapa Gading Hybrida Jakarta Rukan -

Penginapan Aceh

NAMA-NAMA PENGINAPAN DI ACEH Banda Aceh No Nama Penginapan Alamat No. Telp No. Fax Class 1 Hotel Sultan Jl. Sultan Hotel No.1, Peunayong (0651) 22469 (0651) 31770 *** 2 Hotel Cakra Donya Jl. Khairil Anwar No.10 - 12 (0651) 33633 (0651) 23879 * 3 Hotel Kartika Jl. Nyak Adam Kamil IV No.1 (0651) 31205 (0651) 23629 * 4 Hotel Taman Tepi Laut Jl. Banda Aceh-Meulaboh Km 17,55 (0651) 44202, (0651) 44203 * Lhoknga 32029 5 Hotel Medan Jl. Jend. Ahmad Yani No.17 (0651) 33851 (0651) 32256 * Peunayong 21501 6 Hermes Palace Jl. Panglima Nyak Makam, . (0651) 755888. (0651) 7556999 Lampineung 7 Grand Nanggroe Hotel Jl. Tgl. Imum Lueng Bata (0651) 35788. (0651) 35776 35779 8 Griya Indah Pratama Hotel Jl. Taman Makam Pahlawan II No. 2 (0651) 21056 Peuniti 9 Hotel Palembang Jl. Chairil Anwar No. 49 (0651) 22044 10 Hotel Jeumpa Jl. Stadion Dhirmutala No.5 (0651) 7411592 SMK I Banda Aceh 11 Hotel Wisata Jl. Jend. Ahmad Yani No. 19-21 (0651) 21834 12 Hotel Parapat Jl. Jend. Ahmad Yani No. 19 (0651) 22159 13 Hotel Rajawali Jl. Sisinga Mangaraja, Lampulo (0651) 32618 14 Hotel Rasa Mala Indah Jl. Teuku Umar No. 257 Seutui (0651) 41983 15 Hotel Kuala Raja Jl. T. Nyak Arif, (0651) 29687. (0651) 536033 (Depan Rumah Sakit Zainal Abidin) 16 Hotel Oasis Aceh Jl. Tengku Lueng Bata No. 115 (0651) 636999 (0651) 635333 Sabang No Nama Penginapan Alamat No. Telp No. Fax Class 1 Hotel Sabang Hill Jl. Sultan Iskandar Muda (0652) 21207 * 2 Hotel Irma Jl. Seulawah No. 3 (0652) 21235 3 Hotel Pulau Jaya Jl. -

Inside Message from the Executive Director

Volume 4 - March 2013 Inside Page 1 Message from the Executive Director Page 2-5 Summaries of 60/20 Anniversary Activities Page 6-9 American Grantees Section Page 10-24 Indonesian Alumni Section Page 25-28 Alumni Highlights Message from the Executive Director the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA), our embassy colleagues in Jakarta and partners in the private sector, and our Indonesian colleagues in various ministries and offices, universities and secondary schools across the archipelago. We have collaboration on so many levels that when you hear people talk about a Comprehensive Partnership between the United States and the Republic of Indonesia, you can’t help but think of all the AMINEF is able to do in so many positive ways in this regard. While there are many I hope that as you read these components to such a comprehensive wonderful highlights and reflections of partnership, education can only be seen as AMINEF’s Fulbright and related grant one of the keystones of such cooperation. programs, you see what I did, there are Our ongoing collaborative programs with reflections that on a personal basis DIKTI, KEMLU, PT Freeport, and other demonstrate the richness, the essence, entities, are strong evidence of the desire Fulbright Indonesian and the power of educational exchange to collaborate even more in the future. Newsletter is published opportunities on individuals and on a by : broader level the communities with whom I would like to thank all of the grantees have the opportunity to learn, Indonesian and American grantees that AMINEF collaborate, and experience. have shared their stories for this edition of the newsletter and to all of our grantees CIMB Niaga Plaza Fulbright and the other many we wish continued success. -

List of English and Native Language Names

LIST OF ENGLISH AND NATIVE LANGUAGE NAMES ALBANIA ALGERIA (continued) Name in English Native language name Name in English Native language name University of Arts Universiteti i Arteve Abdelhamid Mehri University Université Abdelhamid Mehri University of New York at Universiteti i New York-ut në of Constantine 2 Constantine 2 Tirana Tiranë Abdellah Arbaoui National Ecole nationale supérieure Aldent University Universiteti Aldent School of Hydraulic d’Hydraulique Abdellah Arbaoui Aleksandër Moisiu University Universiteti Aleksandër Moisiu i Engineering of Durres Durrësit Abderahmane Mira University Université Abderrahmane Mira de Aleksandër Xhuvani University Universiteti i Elbasanit of Béjaïa Béjaïa of Elbasan Aleksandër Xhuvani Abou Elkacem Sa^adallah Université Abou Elkacem ^ ’ Agricultural University of Universiteti Bujqësor i Tiranës University of Algiers 2 Saadallah d Alger 2 Tirana Advanced School of Commerce Ecole supérieure de Commerce Epoka University Universiteti Epoka Ahmed Ben Bella University of Université Ahmed Ben Bella ’ European University in Tirana Universiteti Europian i Tiranës Oran 1 d Oran 1 “Luigj Gurakuqi” University of Universiteti i Shkodrës ‘Luigj Ahmed Ben Yahia El Centre Universitaire Ahmed Ben Shkodra Gurakuqi’ Wancharissi University Centre Yahia El Wancharissi de of Tissemsilt Tissemsilt Tirana University of Sport Universiteti i Sporteve të Tiranës Ahmed Draya University of Université Ahmed Draïa d’Adrar University of Tirana Universiteti i Tiranës Adrar University of Vlora ‘Ismail Universiteti i Vlorës ‘Ismail -

Potret Pahlawan Dalam Karya Tapestri

POTRET PAHLAWAN DALAM KARYA TAPESTRI ARTIKEL FITRIA ERVIANI PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SENI RUPA JURUSAN SENI RUPA FAKULTAS BAHASA DAN SENI UNIVERSITAS NEGERI PADANG Wisuda Periode September 2017 Abstrak Berbahasa Indonesia Abstrak Tujuan pembuatan karya akhir ini adalah menciptakan tujuh potret pahlawan Indonesia teknik tapestry, dengan alasan karena pengorbanan, perjuangan, dan tindakan mereka yang sangat berarti dan bermanfaat bagi masyarakat. Alasan lain generasi muda sekarang kurang menghargai jasa para pahlawan, dan rasa nasionalismenya kian memudar. Oleh karena itu, penulis mengambil tema potret pahlawan sebagai subjek dalam berkarya. Metode proses penciptaan karya : pertama, persiapan dengan cara melakukan pengamatan. Kedua, elaborasi, ketiga, tahap sintesis, keempat, realisasi konsep yaitu membuat sketsa, persiapan alat dan bahan, memindahkan sketsa, proses berkarya, dan finishing. Kelima, penyelesaian yaitu pameran dan pembuatan katalog dan laporan. Hasil karya, potret pahlawan Indonesia yakni Raden Ajeng Kartini, Cut Nyak Meutia, Sultan Hasanudin, Jenderal Sudirman, Imam Bonjol, Ir. Soekarno, dan Teuku Umar. Diharapkan karya akhir bermanfaat bagi mahasiswa jurusan seni rupa, sebagai bahan apresiasi dan karya pembanding untuk menciptakan karya tapestri yang lebih baik di masa yang akan datang. Kata Kunci : Potret Pahlawan, Tapestri Abstrak Berbahasa Inggris Abstract The purpose of making this final work is for creating seven potraits Indonesian’s heroes of dashing tapestry techiques. With reason because of sacrifices, stuggles, and actions that giving meaning and benefits for society. Other reason, today the younger generations are less appreciative of the heroes and their sense of nationalism is fading away. Therefore, the author takes a theme about as a subject in this work. The method of creation processnof work : first, preparation bay way doing observatio. -

Daftar Arsip Statis Foto Kementerian Penerangan RI : Wilayah DKI Jakarta 1950 1 11 1950.08.15 Sidang BP

ISI INFORMASI ARSIP FOTO BIDANG POLITIK DAN PEMERINTAHAN KURUN KEGIATAN / NO. POSITIF/ NO ISI INFORMASI UKURAN FOTOGRAFER KETERANGAN WAKTU PERISTIWA NEGATIF 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 1950.08.15 Sidang Pertama Ketua DPR Sartono sedang membuka sidang pertama Dewan 50001 5R v. Eeden Dewan Perwakilan Perwakilan Rakyat, duduk di sebelahnya, Menteri Rakyat Penerangan M.A. Pellaupessy. 2 Presiden Soekarno menyampaikan pidato di depan Anggota 50003 5R v. Eeden DPR di Gedung Parlemen RIS. [Long Shot Suasana sidang gabungan antara Parlemen RI dan RIS di Jakarta. Dalam rapat tersebut Presiden Soekarno membacakan piagam terbentuknya NKRI dan disetujui oleh anggota sidang.] 3 Presiden Soekarno keluar dari Gedung DPR setelah 50005 5R v. Eeden menghadiri sidang pertama DPR. 4 Perdana Menteri Mohammad Natsir sedang bercakap-cakap 50006 5R v. Eeden dengan Menteri Dalam Negeri Mr. Assaat (berpeci) setelah sidang DPR di Gedung DPR. 5 Lima orang Anggota DPR sedang berunding bersama di 50007 5R v. Eeden sebuah ruangan di Gedung DPR, setelah sidang pertama DPR. 6 Ketua Sementara DPR Dr. Radjiman Wedyodiningrat sedang 50008 5R v. Eeden membuka sidang pertama DPR, di sebelah kanannya duduk Sekretaris. 7 Ketua Sementara DPR Dr. Radjiman Wedyodiningrat sedang 50009 5R v. Eeden membuka sidang pertama DPR, di sebelah kirinya duduk Ketua DPR Mr. Sartono. 8 Suasana ruangan pada saat sidang pertama DPR Negara 50010 5R v. Eeden Kesatuan. 9 [1950.08.15] Sidang BP. KNIP Suasana sidang Badan Pekerja Komite Nasional Indonesia 5R Moh. Irsjad 50021 Pusat (BP. KNIP) di Yogyakarta. 10 Presiden Soekarno sedang berpidato sidang BP. KNIP di 5R 50034 Yogyakarta.