To Whom Does a Wronged Man Turn for Help? the Agent in Old Babylonian Letters. by Shirley Graetz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sumerian King List the Sumerian King List (SKL) Dates from Around 2100 BCE—Near the Time When Abram Was in Ur

BcResources Genesis The Sumerian King List The Sumerian King List (SKL) dates from around 2100 BCE—near the time when Abram was in Ur. Most ANE scholars (following Jacobsen) attribute the original form of the SKL to Utu-hejel, king of Uruk, and his desire to legiti- mize his reign after his defeat of the Gutians. Later versions included a reference or Long Chronology), 1646 (Middle to the Great Flood and prefaced the Chronology), or 1582 (Low or Short list of postdiluvian kings with a rela- Chronology). The following chart uses tively short list of what appear to be the Middle Chronology. extremely long-reigning antediluvian Text. The SKL text for the following kings. One explanation: transcription chart was originally in a narrative form or translation errors resulting from and consisted of a composite of several confusion of the Sumerian base-60 versions (see Black, J.A., Cunningham, and the Akkadian base-10 systems G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., of numbering. Dividing each ante- and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text diluvian figure by 60 returns reigns Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http:// in harmony with Biblical norms (the www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford bracketed figures in the antediluvian 1998-). The text was modified by the portion of the chart). elimination of manuscript references Final versions of the SKL extended and by the addition of alternative the list to include kings up to the reign name spellings, clarifying notes, and of Damiq-ilicu, king of Isin (c. 1816- historical dates (typically in paren- 1794 BCE). thesis or brackets). The narrative was Dates. -

2210 Bc 2200 Bc 2190 Bc 2180 Bc 2170 Bc 2160 Bc 2150 Bc 2140 Bc 2130 Bc 2120 Bc 2110 Bc 2100 Bc 2090 Bc

2210 BC 2200 BC 2190 BC 2180 BC 2170 BC 2160 BC 2150 BC 2140 BC 2130 BC 2120 BC 2110 BC 2100 BC 2090 BC Fertile Crescent Igigi (2) Ur-Nammu Shulgi 2192-2190BC Dudu (20) Shar-kali-sharri Shu-Turul (14) 3rd Kingdom of 2112-2095BC (17) 2094-2047BC (47) 2189-2169BC 2217-2193BC (24) 2168-2154BC Ur 2112-2004BC Kingdom Of Akkad 2234-2154BC ( ) (2) Nanijum, Imi, Elulu Imta (3) 2117-2115BC 2190-2189BC (1) Ibranum (1) 2180-2177BC Inimabakesh (5) Ibate (3) Kurum (1) 2127-2124BC 2113-2112BC Inkishu (6) Shulme (6) 2153-2148BC Iarlagab (15) 2121-2120BC Puzur-Sin (7) Iarlaganda ( )(7) Kingdom Of Gutium 2177-2171BC 2165-2159BC 2142-2127BC 2110-2103BC 2103-2096BC (7) 2096-2089BC 2180-2089BC Nikillagah (6) Elulumesh (5) Igeshaush (6) 2171-2165BC 2159-2153BC 2148-2142BC Iarlagash (3) Irarum (2) Hablum (2) 2124-2121BC 2115-2113BC 2112-2110BC ( ) (3) Cainan 2610-2150BC (460 years) 2120-2117BC Shelah 2480-2047BC (403 years) Eber 2450-2020BC (430 years) Peleg 2416-2177BC (209 years) Reu 2386-2147BC (207 years) Serug 2354-2124BC (200 years) Nahor 2324-2176BC (199 years) Terah 2295-2090BC (205 years) Abraham 2165-1990BC (175) Genesis (Moses) 1)Neferkare, 2)Neferkare Neby, Neferkamin Anu (2) 3)Djedkare Shemay, 4)Neferkare 2169-2167BC 1)Meryhathor, 2)Neferkare, 3)Wahkare Achthoes III, 4)Marykare, 5)............. (All Dates Unknown) Khendu, 5)Meryenhor, 6)Neferkamin, Kakare Ibi (4) 7)Nykare, 8)Neferkare Tereru, 2167-2163 9)Neferkahor Neferkare (2) 10TH Dynasty (90) 2130-2040BC Merenre Antyemsaf II (All Dates Unknown) 2163-2161BC 1)Meryibre Achthoes I, 2)............., 3)Neferkare, 2184-2183BC (1) 4)Meryibre Achthoes II, 5)Setut, 6)............., Menkare Nitocris Neferkauhor (1) Wadjkare Pepysonbe 7)Mery-........, 8)Shed-........, 9)............., 2183-2181BC (2) 2161-2160BC Inyotef II (-1) 2173-2169BC (4) 10)............., 11)............., 12)User...... -

Part 6: Old Testament Chronology, Continued

1177 Part 6: Old Testament Chronology, continued. Part 6C: EXTRA-BIBLICAL PRE-FLOOD & POST-FLOOD CHRONOLOGIES. Chapter 1: The Chronology of the Sumerian & Babylonian King Lists. a] The Post-Flood King Lists 1, 2, 3, & 4. b] The Pre-Flood King Lists 1, 2, & 3. Chapter 2: The Egyptian Chronology of Manetho. a] General Introduction. b] Manetho’s pre-flood times before Dynasty 1. c] Manetho’s post-flood times in Dynasties 1-3. d] Post-flood times in Manetho’s Dynasties 4-26. Chapter 3: Issues with some other Egyptian chronologies. a] The Appollodorus or Pseudo-Appollodorus King List. b] Inscriptions on Egyptian Monuments. c] Summary of issues with Egyptian Chronologies & its ramifications for the SCREWY Chronology’s understanding of the Sothic Cycle. d] A Story of Two Rival Sothic Cycles: The PRECISE Chronology & the SCREWY Chronology, both laying claim to the Sothic Cycle’s anchor points. e] Tutimaeus - The Pharaoh of the Exodus on the PRECISE Chronology. Chapter 4: The PRECISE Chronology verses the SCREWY Chronology: Hazor. Chapter 5: Conclusion. 1178 (Part 6C) CHAPTER 1 The Chronology of the Sumerian & Babylonian King Lists. a] The Post-Flood King Lists 1, 2, 3, & 4. b] The Pre-Flood King Lists 1, 2, & 3. (Part 6C, Chapter 1) The Chronology of the Sumerian & Babylonian King List: a] The Post-Flood King Lists 1, 2, 3, & 4. An antecedent question: Are we on the same page: When do the first men appear in the fossil record? The three rival dating forms of the Sumerian King List. (Part 6C, Chapter 1) section a], subsection i]: An antecedent question: Are we on the same page: When do the first men appear in the fossil record? An antecedent question is, Why do I regard the flood dates for Sumerian and Babylonian King Lists (and later in Part 6C, Chapter 2, the Egyptian King List) as credible, or potentially credible? The answer relates to my understanding of when man first appears in the fossil record vis-à-vis the dates found in a critical usage of these records for a Noah’s Flood date of c. -

Relations Betyveen the Language of the Gutians and Old Turkish

RELATIONS BETYVEEN THE LANGUAGE OF THE GUTIANS AND OLD TURKISH KEMAL BALKAN* The details presented belovv on the history of the Gutians and their language have been gleaned from the lectures of my former professor, the late B. Landsberger and are in particular inspired by a communication he presented at the Second Congress of Turkish History. This communica tion of Landsberger has, in contrast to his other publications, hardly evoked the interest of scientific circles. It may be said that, vvith a fevv ex- ception, it has not been referred to in Turkish publications either. This may be due to the fact that the communication in question is of an early date (1937) and that it is diflicult to fınd the original German version of it anyvvhere. It should be noted here that in the present article the reading of some of the vvords had to be modified. In the light of the above-mentioned circumstances it was deemed ne- cessary to republish this important article of Landsberger and it was also considered appropriate to recall to the mind the cherished memory of my former teacher and mentor. I must, on this occasion, thank Professor Ay dın Sayılı who has been of great assistance in the publication of this arti cle. Professor Aydın Sayılı is also an admiror of Professor Landsberger. I shall start this article by presenting the above-mentioned communi cation of Professor Landsberger. Grundfragen der Frühgeschichte Vorderasiens* * Durch Ausgrabungen und Forschungen tritt die Welt des vorgrie- chischen Altertums immer deutlicher vor unsere Augen. Die Weltge- schichte hat sich, vvenn wir sie mit dem ersten Auftauchen schriftilicher Quellen beginnen lassen, um mindestens 2500 Jahre verlângert. -

![The Akkadian Empire /Əˈkeɪdiən/[2] Was an Empire Centered in the City](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9306/the-akkadian-empire-ke-di-n-2-was-an-empire-centered-in-the-city-5259306.webp)

The Akkadian Empire /Əˈkeɪdiən/[2] Was an Empire Centered in the City

Akkad The Akkadian Empire /əˈkeɪdiən/[2] was an empire centered in the city of Akkad /ˈækæd/[3] and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia which united all the indigenous Akkadian speakingSemites and the Sumerian speakers under one rule.[4] During the 3rd millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Semitic Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism.[5] Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as a spoken language somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC (the exact dating being a matter of debate).[6] The Akkadian Empire reached its political peak between the 24th and 22nd centuries BC, following the conquests by its founder Sargon of Akkad (2334–2279 BC). Under Sargon and his successors, Akkadian language was briefly imposed on neighboring conquered states such as Elam. Akkad is sometimes regarded as the first empire in history,[7] though there are earlier Sumerian claimants.[8] After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, the Akkadian peoples of Mesopotamia eventually coalesced into two major Akkadian speaking nations; Assyria in the north, and a few centuries later,Babylonia in the south. Contents [hide] 1 City of Akkad 2 History o 2.1 Origins . 2.1.1 Sargon and his sons . 2.1.2 Naram-Sin o 2.2 Collapse of the Akkadian Empire o 2.3 The Curse 3 Government 4 Economy 5 Culture o 5.1 Language o 5.2 Poet – priestess Enheduanna o 5.3 Technology o 5.4 Achievements 6 See also 7 Notes 8 Further reading 9 External links 1 City of Akkad Main article: Akkad (city) The precise archaeological site of the city of Akkad has not yet been found.[9] The form Agade appears in Sumerian, for example in the Sumerian King List; the later Assyro-Babylonian form Akkadû ("of or belonging to Akkad") was likely derived from this. -

OXFORD EDITIONS of CUNEIFORM TEXTS the Weld-Blundell

OXFORD EDITIONS OF CUNEIFORM TEXTS Edited under the Direction of S. LANGDON, Professor of Assyriology. VOLUME II The Weld-Blundell Collection, vol. II. Historical Inscriptions, Containing Principally the Chronological Prism, W-B. 444, by S. LANGDON, M. A. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai Humphrey Milford 1923 PREFACE. The fortunate discovery of the entire chronological tables of early Sumerian and Bbylonian history provides ample reason for a separate volume of the Weld-Blundell Series, and thle imme- diate publication of this instructive inscription is imperative. It constitutes the most important historical document of its kind ever recovered among cuneiform records. The Collection of the Ashmolean Museum contains other historical records which I expected to include in this volume, notably the building inscriptions of Kish, excavated during the first year's work of the Oxford and Field Museum Expedition. MR. WELD-BLUNDELL who supports this expedition on behalf of The University of Oxford rightly expressed the desire to have his dynastic prism prepared for publication before the writer leaves Oxford to take charge of the excavations at Oheimorrl (Kish) the coming winter. This circumstance necessitates the omission of a considerable nulmber of historical texts, which must be left over for a future volume. I wish also that many of the far reaching problems raised by the new dynastic prism might have received more mature discussion. The most vital problem, concerning which I am at present unable to decide, namely the date of the first Babylonian dynasty, demands at least special notice some-where in this book. -

Compendium of World History Vol. I (Herman L. Hoeh)

COMPENDIUM OF WORLD HISTORY VOLUME 1 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Ambassador College Graduate School of Theology In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Theology by Herman L. Hoeh 1962 (1963-1965, 1967 Edition) TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One ..... The Modern Interpretation of History A Radical New View How History Is Written Not Without Bias A Case History "Anything but Historical Truth" History Involves Interpretation The Truth about the "Historical Method" Evidence of God Rejected as "Myth" History Cut from Its Moorings Chapter Two ..... 6000 Years of History It Is Never Safe to Assume No "Prehistory" of Man Cultures, Not "Ages" Origin of the Study of History Historians Follow the Higher Critics Framework of History Founded on Egypt Is Egyptian History Correct? Distorting History Chapter Three ..... History Begins at Babel History Corroborates the Bible On To Egypt The Chronology of Dynasty I Shem in Egypt Dynasty II of Thinis Joseph and the Seven Years' Famine The Exodus Pharaoh of the Exodus Dynasty IV -- The Pyramid Builders Chapter Four ..... The Missing Half of Egypt's History The Story Unfolds Moses the General History of Upper Egypt The Great Theban Dynasty XII Who Was Rameses? Chapter Five ..... Egypt After the Exodus Who Were the Invaders? The Great Shepherds Hyksos in Book of Sothis Amalekites after 1076 Chapter Six ..... The Revival of Egypt Dynasty XVIII The Biblical Parallel Shishak Captures Jerusalem Who Was Zerah the Ethiopian? Dynasty XVIII in Manetho The Book of Sothis Chapter Seven ..... The Era of Confusion Egypt As It Really Was The Later Eighteenth Dynasty Manetho's Evidence The El-Amarna Letters Are the "Habiru" Hebrews? After El-Amarna Chapter Eight .... -

The Sumerians

THE SUMERIANS THE SUMERIANS THEIR HISTORY, CULTURE, AND CHARACTER Samuel Noah Kramer THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1963 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved Published 1963 Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0-226-45237-9 (clothbound); 0-226-45238-7 (paperbound) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 63-11398 89 1011 12 To the UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA and its UNIVERSITY MUSEUM PREFACE The year 1956 saw the publication of my book From the Tablets of Sumer, since revised, reprinted, and translated into numerous languages under the title History Begins at Sumer. It consisted of twenty-odd disparate essays united by a common theme—"firsts" in man s recorded history and culture. The book did not treat the political history of the Sumerian people or the nature of their social and economic institutions, nor did it give the reader any idea of the manner and method by which the Sumerians and their language were discovered and "resurrected/' It is primarily to fill these gaps that the present book was conceived and composed. The first chapter is introductory in character; it sketches briefly the archeological and scholarly efforts which led to the decipher ment of the cuneiform script, with special reference to the Sumerians and their language, and does so in a way which, it is hoped, the interested layman can follow with understanding and insight. The second chapter deals with the history of Sumer from the prehistoric days of the fifth millennium to the early second millennium B.C., when the Sumerians ceased to exist as a political entity. -

THE SUMERIAN KING LIST Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ASSYRIOLOGICAL STUDIES JOHN ALBERT WILSON & THOMAS GEORGE ALLEN • EDITORS oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu THE SUMERIAN KING LIST oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu THE SUMERIAN KING LIST BT THORKILD JACOBSEN THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ASSTRIOLOGICAL STUDIES . NO. 11 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS • CHICAGO • ILLINOIS Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber oi.uchicago.edu International Standard Book Number: 0-226-62273-8 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 39-19328 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1939 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1939, Fourth Impression 1973. Printed by Cushing-Malloy, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TO O. E. RAVN, TO THE MEMORY OF EDWARD CHIERA AND TO H. FRANKFORT ARE THESE STUDIES DEDICATED oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE The incentive to the studies here presented was furnished by the excava tions of the Oriental Institute at Tell Asmar. When in the season of 1931/32 we opened up strata of Agade and Early Dynastic times, the chronology of these periods naturally occupied our thoughts greatly, and the author felt prompted to resume earlier, more perfunctory studies of the Sumerian King List. The main ideas embodied in the present work took shape that season in the evenings, after days spent in the houses and among the remains of the periods with which the King List deals. -

Sumeryjska Lista Królów

Sumeryjska Lista Królów Po tym jak królestwo zostało dane z nieba, królestwo było w Eridu. W Eridu Alulim był królem, panował przez 28 800 lat. Alalgar panował przez 36 000 lat. Dwóch królów panowało przez 64 800 lat. Następnie Eridu zostało porażone orężem i królestwo zostało przeniesione do Bad-tibiry. W Bad-tibirze Enmen-lu-ana panował przez 43 200 lat. Enmen-gal-ana panował przez 28 800 lat. Boski Dumuzi, pasterz panował przez 36 000 lat. Trzech królów panowało przez 108 000 lat. Następnie Bad-tibira została porażona orężem i królestwo zostało przeniesione do Larak W Larak En-sipad-zid-ana panował przez 28 800 lat. Jeden król panował przez 28 800 lat. Następnie Larak zostało porażone orężem i królestwo zostało przeniesione do Sippar. W Sippar Enmen-dur-ana panował przez 21 000 lat. Jeden król panował przez 21 000 lat. Sumeryjska Lista Królów z języka angielskiego przetłumaczył Łukasz Sitnik opublikowano na: www.starozytnysumer.pl Następnie Sippar zostało porażone orężem i królestwo zostało przeniesione do Szuruppak. W Szuruppak Ubara-Tutu panował przez 18 600 lat. Jeden król panował przez 18 600 lat. Ośmiu królów w pięciu miastach panowało przez 385 200 lat. A potem potop zmiótł wszystko. Po tym jak potop zmiótł wszystko królestwo ponownie zostało dane z nieba, królestwo było w Kiszu. W Kiszu Giszur był królem, panował przez 1 200 lat. Kullassina-bel był królem, panował przez 900 lat. Nan-gisz-liszma był królem, panował przez 1 200 lat. En-dara-ana był królem, panował przez 420 lat, 3 miesiące i 3 i pół dnia. Babum był królem, panował przez 300 lat. -

Dr Herman L Hoeh's Notes for the Revised Compendium of World History

Dr Herman L Hoeh’s Notes for the revised Compendium of World History Assembled by Craig M White Contents 1. A Look into the First 17 Centuries 2. The Kings of Nineveh after Nimrod 3. Differences in Reckoning Eras in Assyria 4. Isin II and Assyria 5. Kings of Kish 6. The Dynasty of Akkad and the Guti 7. Babylon 8. History of Armenia 9. The Sealand Dynasty in Sumer What became of the Compendium of World History? During a clean up I discovered a number of handwritten notes by Dr Hoeh that was going to form part of his revised Compendium. Two members spent a considerable amount of time re- typing them I and have assembled these for your edification. I know that he was revising it as he told me that it ‘would very definitely’ be published. As you will see below, most of volume 1 of the Compendium had been rejected by Dr Herman L Hoeh and he was in the process of revising it; but much of volume 2 seemingly remained valid. Note also that the Compendium went through a number of edits prior to his withdrawing it. For instance volume I carried copyright dates of 1963, 1963-65, 1966, 1967, 1969, and 1970, while volume II had copyright dates of 1963, 1966, and 1969. Each revision was followed by a long list of errata. Dr Hoeh’s Notes for the revised Compendium It is rather unfortunate that Dr Hoeh’s revised Compendium may not have ever been completed. He surely had many notes for this and no doubt much was thrown out or lost after he died. -

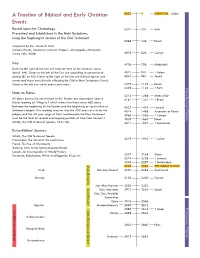

A Timeline of Biblical and Early Christian Events

A Timeline of Biblical and Early Christian 5501 1 CREATION Adam Events Based upon the Chronology 5271 231 Seth Presented and Established in the Holy Scriptures, using the Septuagint version of the Old Testament 5066 436 Enosh Compiled by Rev. David A. Kind Campus Pastor, University Lutheran Chapel - Minneapolis, Minnesota Trinity XXIII, 2008 4876 626 Cainan Key: 4706 796 Mahalalel Dates to the right of the line are from the time of the creation, (Anno Mundi, AM). Dates to the left of the line are according to conventional 4571 931 † Adam dating (BC or AD). Events to the right of the line are Biblical figures and 4541 961 Jared events and those most directly effecting the Old or New Testament Church. Those to the left are world events and rulers. 4379 1123 Enoch 4359 1143 † Seth P RE Note on Dates: -D 4214 1288 Methuselah ELUVIAN All dates before the construction of the Temple are dependant upon a 4161 1341 † Enosh literal reading of I Kings 6:1 which states that there were 480 years between the beginning of the Exodus and the beginning of construction on 4027 1475 Lamech P Solomon’s temple. This reading requires that the 450 years of rule by the 4014 1488 Ascension of Enoch ERIO judges, and the 40 year reign of Saul, mentioned in the New Testament 3966 1536 † Cainan must be the total of several overlapping periods of time (See Samuel J. 3839 1663 Noah D Schulz, The Old Testament Speaks, 103-104). 3811 1691 † Mahalalel Extra-Biblical Sources: Schulz, The Old Testament Speaks Franzmann, The Word of the Lord Grows 3579 1923 † Jared Frend, The Rise of Christianity Surburg, Intro.