Slums, Social Uplift, and the Remaking of Wooster Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apartment Buildings in New Haven, 1890-1930

The Creation of Urban Homes: Apartment Buildings in New Haven, 1890-1930 Emily Liu For Professor Robert Ellickson Urban Legal History Fall 2006 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Defining and finding apartments ............................................................................................ 4 A. Terminology: “Apartments” ............................................................................................... 4 B. Methodology ....................................................................................................................... 9 III. Demand ............................................................................................................................. 11 A. Population: rise and fall .................................................................................................... 11 B. Small-scale alternatives to apartments .............................................................................. 14 C. Low-end alternatives to apartments: tenements ................................................................ 17 D. Student demand: the effect of Yale ................................................................................... 18 E. Streetcars ........................................................................................................................... 21 IV. Cultural acceptance and resistance .................................................................................. -

GREATER NEW HAVEN Community Index 2016

GREATER NEW HAVEN Community Index 2016 Understanding Well-Being, Economic Opportunity, and Change in Greater New Haven Neighborhoods A CORE PROGRAM OF In collaboration with The Community Foundation for Greater New Haven and other community partners and a Community Health Needs Assessment for the towns served by Yale-New Haven Hospital and Milford Hospital. Greater New Haven Community Index 2016 Understanding well-being, economic opportunity, and change in Greater New Haven neighborhoods MAJOR FUNDERS Other Funders The Greater New Haven Community Index makes extensive use of the 2015 DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey, which completed in-depth interviews with 16,219 randomly-selected adults in Connecticut last year. In addition to the major funders listed above, supporters of the survey’s interviews with 1,810 adults in Greater New Haven as well as related data dissemination activities included the City of New Haven Health Department, United Way of Greater New Haven, Workforce Alliance, NewAlliance Foundation, Yale Medical Group, Connecticut Health Foundation, Connecticut Housing Finance Authority, and the Community Alliance for Research and Engagement at the Yale School of Public Health among others. Please see ctdatahaven.org for a complete list of statewide partners and funders. Lead Authors Mark Abraham, Executive Director, DataHaven Mary Buchanan, Project Manager, DataHaven Co-authors and contributors Ari Anisfeld, Aparna Nathan, Camille Seaberry, and Emma Zehner, DataHaven Amanda Durante and Fawatih Mohamed, University of Connecticut -

The Shanachie, Volume 25, Number 1

Vol. XXV No. 1 Connecticut Irish-American Historical Society 2013 www.ctiahs.com Paddy & Bridget & Wooster Square In the late 1820s, Irish immigrants established one of the first two ethnic neighborhoods in New Haven at Chapel and Chestnut streets near Wooster Square. This Shanachie is devoted entirely to the story of that enclave and the thriving Irish neighborhood it became throughout the rest of the 19th century. St. Patrick’s Church at Grand and Wallace was for Irish immigrants the religious and ethnic center of the Wooster neighborhood. A canal worker’s legacy: New Haven’s first Irish neighborhood n the 1820s and 1830s, New Haven experi- Guinea; the other, an Irish-American neighbor- town after 1812, and … which earned William I enced its first major expansion. Develop- hood known as Slineyville. Both raised some Lanson a place in the history of American ment projects just east of the city’s original eyebrows among old-time New Haveners. engineering and construction in general, and in downtown nine squares opened for settlement One historian described Slineyville simply as New Haven history in particular.” lands as far east as the Mill River. The whole “untidy,” and New Guinea as “of similar Lanson’s New Guinea grew up spontaneous- development area was known as “New Town- grade.” Whatever their other works and attrib- ly around the intersection of Chapel and Frank- ship.” utes, what caught the attention of that historian lin streets. Slineyville, not only the first Irish One part of the New Township was the well- was that the two men most prominently con- enclave but the first of many ethnic European organized project of Wooster Square where nected with the enclaves — William Lanson neighborhoods in New Haven, grew similarly streets lined with handsome homes were laid and John Sliney — each kept a house of “resort just a block west of New Guinea at Chapel and out around an idyllic green. -

Table of Contents

2018 Condominium Management 1 Table of Contents B Branford.......5-6 C Cheshire.......7 Clinton..........8 Condominium Management Companies.......2–4 E East Haven.......9-10 G Guilford.......11 H Hamden......12-14 M Madison .......15 Meriden......16-18 Milford.......19-21 N New Haven.......22-26 North Branford - Northford.......27 North Haven.......27 O Old Saybrook......28 Orange.......29 S Southington.......29-30 W Wallingford.......31-32 West Haven...... 33-34 While every effort has been made to ensure the reliability of the information presented in this publication, The New Haven Middlesex Association of REALTORS®, Inc. does not guarantee the accuracy of Updated 9/25/18 the data contained herein. Errors brought to the atten- tion of the publisher and verified by our staff, will be corrected in future editions. This publication is based on information from members of the New Haven Middlesex Association of REALTORS® 2018 Condominium Management 2 Condominium Management Companies Collect Association ............................................ (203) 924-5331 AB Property Management, LLC ......................... (860) 828-0620 392 River Rd. P O Box 7373 Shelton, Ct 06484 Kensington, CT 06037 Connecticut Condo Connection (was R&R) ..... (203) 720-3777 APMC, LLC ........................................................ (800) 967-1209 24 Cherry St. 14 Robin La. Naugatuck, CT 06770 Killingworth CT 06419 Connecticut Real Estate Management ............... (203) 699-9335 Advanced Property Management ........................ (860) 657-8970 50 Southwick Ct., 2nd flr, 36 Commerce St. Cheshire, Ct. 06410 Glastonbury, CT. 06033 Concord Group .................................................... (203) 922-7878 All In Property Management ............................. (203) 725-1938 292-294 Roosevelt Dr. ........................................ phone not in service 1449 Old Waterbury Road Seymour, CT 06483 Ste 307, Southbury, CT 06488 Consolidated Management Group (CMG) ......... -

Final Draft-New Haven

Tomorrow is Here: New Haven and the Modern Movement The New Haven Preservation Trust Report prepared by Rachel D. Carley June 2008 Funded with support from the Tomorrow is Here: New Haven and the Modern Movement Published by The New Haven Preservation Trust Copyright © State of Connecticut, 2008 Project Committee Katharine Learned, President, New Haven Preservation Trust John Herzan, Preservation Services Officer, New Haven Preservation Trust Bruce Clouette Robert Grzywacz Charlotte Hitchcock Alek Juskevice Alan Plattus Christopher Wigren Author: Rachel D. Carley Editor: Penny Welbourne Rachel D. Carley is a writer, historian, and preservation consultant based in Litchfield, Connecticut. All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Rights to images in the collection of the New Haven Museum and Historical Society are granted for one- time use only. All photographs by Rachel Carley unless otherwise credited. Introduction Supported by a survey and planning grant from the History Division of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism, this overview of modern architecture and planning in New Haven is the first phase of a comprehensive project sponsored by the New Haven Preservation Trust. The intent is to investigate how and why the city became the center for one of the country’s most aggressive modern building programs of the post-World War II era, attracting a roster of internationally recognized architects and firms considered to be among the greatest leaders of the modernist movement. Although the architectural heritage of this city includes fine examples of early 20th- century contemporary design predating the war, the New Haven story relates most directly to the urban renewal years of the 1950s to 1970s and their dramatic reshaping of the city skyline during that period. -

X. APPENDIX B – Profile of City of New Haven

X. APPENDIX B – Profile of City of New Haven Welcome to New Haven! Strategically situated in south central Connecticut, New Haven is the gateway to New England, a small city which serves as a major transportation and economic hub between New York and Boston. Justly known as the cultural capital of Connecticut, New Haven is a major center for culture and entertainment, as well as business activity, world‐class research and education. As the home to Yale University and three other colleges and universities, New Haven has long been hub of academic training, scholarship and research. Anchored by the presence of Yale University and numerous state and federal agencies, New Haven is a major center for professional services, in particular architecture and law. And drawing on a spirit of Yankee ingenuity that dates to Eli Whitney, New Haven continues to be a significant manufacturing center; the city is home to high‐tech fabrics company Uretek, Inc., Assa Abloy, makers of high tech door security systems, and a vibrant food manufacturing sector. In 2009, surgical products manufacturer Covidien announced its headquarters and 400 Executive and support positions would relocate to New Haven’s Long Wharf. In 2013, Alexion Pharmaceuticals announced its plans to construct a 500,000sf global headquarters for its growing biotech company which will open in 2015. More importantly, the City of New Haven and its partners are investing for the future and despite the worst recession of the post‐World War ii era, New Haven is thriving and is in the midst of one of the strongest periods of business growth in decades. -

BUILDING a SEGREGATED CITY: HOW WE ALL WORKED Togethert

BUILDING A SEGREGATED CITY: HOW WE ALL WORKED TOGETHERt ROBERT A. SOLOMON* I. INTRODUCTION The story of American cities is usually told as the story of progressive waves of immigrants, establishing neighborhoods, and adding to the texture of the overall fabric of the city. Since World War II, however, the trend in cities has been one of shrinking population, increased minority (primarily African- American) population in the center city and a circle of wealthier, whiter sub- urbs on the fringes or outside the city. The modem American city is defined as much by who left as by who stayed. The result is a city which is often segre- gated, hampered by a weak tax and job base, and characterized by an older and less well-maintained housing stock than the suburbs. While each city has its own unique history and texture, many of the trends leading to segregated, impoverished cities are common. These trends are based not only on population movements, but on federal, state and local poli- cies that make the resulting segregated city all but inevitable. In this paper, I examine New Haven, Connecticut as a model, in the belief that the trends con- cerning segregation, housing policy and poverty are applicable throughout many, if not most, American cities. New Haven is old enough to have been affected by both early and recent immigration. It is a city of neighborhoods serving as a microcosm for larger cities. It is surrounded by a ring of whiter, wealthier suburbs. It had and lost a strong industrial base. Most importantly, it has served as a laboratory for vir- tually every twentieth century social policy experiment, by both the public and private sector. -

GNHWPCA EJPPP Wet Weather Nitrogen Project Submission

Environmental Justice Public Participation Plan OP R ! "O! P"%%%& &' ' O P Part I: Proposed Applicant Information 1. APPLICANT INFORMATION Greater New Haven Water Pollution Control Authority 260 East Street New Haven CT 06511 203-466-5280 321 Tom Sgroi [email protected] R ✔ 2. WILL YOUR PERMIT APPLICATION INVOLVE: ✔ 3. FACILITY NAME AND LOCATION East Shore Water Pollution Abatement Facility & Pre-Treatment Sta. 345 East Shore Parkway (See Attached) New Haven CT 06512 052 950 400, 600, 800 Part II: Informal Public Meeting Requirements R A. Identify Time and Place of Informal Public Meeting date, time and placeR June 21, 2012 New Haven Sound School Regional Vocational Aquaculture Center, 60 South Water St., New Haven, CT 06519 6:30pm ! " # $ % & ' ( ) * ( ))) & B. Identify Communication Methods By Which to Publicize the Public Meeting New Haven Register and La Voz June 11, 2012 (NHR), June 8, 2012 (La Voz) +, - % ) . / & 0 ( 123+$!$+"3$$ # 3 "3 Part II: Informal Public Meeting Requirements (continued) ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ R Part III: Measures to Facilitate Meaningful Public Participation -

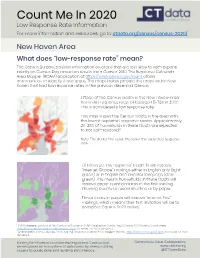

Count Me in 2020 Low Response Rate Information for More Information and Resources, Go to Ctdata.Org/Census/Census-2020

Count Me In 2020 Low Response Rate Information For more information and resources, go to ctdata.org/census/census-2020/ New Haven Area What does “low-response rate” mean? The Census Bureau provides information on areas that are less likely to self-respond initially on Census Day based on results from Census 2010. The Response Outreach Area Mapper (ROAM) application at https://www.census.gov/roam allows communities to identify these areas. The maps below provide the areas within New Haven that had low response rates in the previous decennial Census. Fifteen of the Census Tracts in the New Haven-area had initial response rates of between 5-73% in 2010.1 This is considered a low response rate. This map shows the Census Tracts in the area with 3508 the lowest expected response scores. Approximately 20-38% of households in these tracts are expected to not self—respond.2 Note: The darker the color, the lower the expected response rate. Of these 30 “low response” tracts, 10 will receive “Internet Choice” mailings either in English only (light green) or in English and another language (dark green). This means households in these tracts will receive paper questionnaires in the first mailing, allowing people to respond online or by paper. Those tracts in purple will receive “Internet First” mailings, which means their first invitation will be to complete Census 2020 online. 1 CUNY Mapping Services at the Center for Research, CUNY Graduation Center. (n.d.). Census 2020 Hard to Count map, https://www.censushardtocountmaps2020.us/. Accessed on 2020, January 6. 2 United States Census Bureau. -

NEW HAVEN ★ with a Population of 130,000, New Haven Is the Second Largest City in the State of Connecticut

NEW HAVEN ★ With a population of 130,000, New Haven is the second largest city in the state of Connecticut. It’s the perfect place to stop on the way to New York City. The small city attracts many tourists who come to visit the prestigious Yale University. Founded in 1701, Yale is the oldest university in the United States. You must also try the renowned New Haven pizza, which is widely considered to be among the best in the country, if not the world! CITY HALL OF NEW HAVEN © WikiCommons, A Fandom DESTINATIONS WHAT TO DO — UNIVERSITÉ DE next to the university. It is YALE ★★ surrounded by government, Discover the 300-year history university and historical and the student life of today on buildings, stores, restaurants, the picturesque campus of the museums, art galleries and oldest university in the United two theaters. The park States. features many paths, benches, picnic tables and a central Be sure to visit the university fountain. Concerts and events library. The Beinecke Rare are also held here during the Book & Manuscript Library summer season. The Green contains more than 12 million is bounded by Church Street documents, many of which are to the east, Chapel Street to extremely rare (121 Wall Street the south, Elm Street to the / beinecke.library.yale.edu). north and College Street to the west. YALE UNIVERSITY FROM NEW HAVEN GREEN If you wish to explore the © AdobeStock, f11photo campus on your own, get a Blue YALE’S ART Trail map, which will help you GALLERY ★ find your way around. -

Italian-American Legacy

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1983 Volume VI: Cross-Cultural Variation in Children and Families Italian-American Legacy Curriculum Unit 83.06.03 by Ralph Lambert Introduction: The following unit was constructed for the purpose of educating the 8th grade middle school student on the struggles and contributions of the Italian-Americans of New Haven. The unit will also help to illuminate some of the discriminatory practices against other ethnic groups and their similarities. The Italians came to America to work for a better life for themselves and their children. They came to work on the farm and in the city. The family members each had their role, each was dependent on one another to succeed. When success was imminent they would send for more family living in Italy to come to America and enjoy life, or at least contribute to a better life. Education, business religion and economic conditions in general would eventually determine how or where they would live. New Haven attracted a large portion of the Italian immigrants because of its oyster industry and proximity to the Long Island sound. Not only did they work immediately after their arrival in the late 1800’s but they continued to contribute in other areas of production. Industry played a vital part in the work life of the Italian- American as well as farming on America’s rich soil. Have they succeeded in establishing themselves as a proud culture? Time has past and the future is coming. The feeling is that America sure has done well to welcome the Italians. -

Guide to New Haven Street Trees

Guide to New Haven’s Trees URI Urban Resources Initiative New Haven, Connecticut Guide to New Haven’s Trees URI Urban Resources Initiative New Haven, Connecticut Philip Marshall, Ph.D Acknowledgements The development of this publication is a reflection of the dual mission of the Urban Resources Initiative: to provide Yale students a clinical experience in urban community-based forestry and to foster citizen-driven environmental stewardship. Earlier versions of the book depended on the work of Yale graduate students Yi-Wen Lin and Jacob Holzberg-Pill. Philip Marshall advanced the beta document to this more comprehensive edition, which can readily serve anyone living in or around the City of New Haven. The document is designed to help people develop tree identification skills and guide in the selection of appropriate trees for streetscape plantings. We are especially grateful to Josephine Bush and the Robbins de Beaumont Foundation for their support, which made updating New Haven’s tree inventory and producing this publication possible. Contents Introduction......................................2 List of Tree Species.............................9 Dichotomous Leaf Key................15 Tree Species......................................23 Appendix: Species Suitable for Planting........117 Glossary..............................................123 Sources................................................129 2 Introduction New Haven’s Tree Canopy In 2000, the City of New Haven hired a private firm to conduct a complete census (or inventory) of New Haven’s street trees. The inventory data included 30,000 entries detailing tree species, location, condition (live, dead, stump), size, and maintenance observations. The Department of Parks provided URI the data in 2007 to update the inventory. Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies graduate student Suzy Oversvee, working with Jeff Ward at the Connecticut Agricultural Station, converted the data into a format compatible with ArcGIS.