Why the Mexican Consumer Electronics Industry Failed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OBS Transforming CX

Winning the Global Consumer Electronics Industry A checklist for global, consistent and secure CX "The Age of Experience will be defined by personalized technology that meets your needs… the devices you use will understand you as an individual, blurring the boundaries between the digital and physical worlds." HS KIM President and CEO of Consumer Electronics Division Samsung Electronics Smartphones, smart TVs, laptops and tablets, The global electrical appliances, wearable devices – the US$1 trillion consumer electronics industry permeates every aspect consumer of our lives. It is a proof of the incredible pace of Global consumer electronics innovation around us. electronics market The intense competition especially from many of the size in 2019 industry industry’s Asian leaders such as Samsung, Huawei, Sony, Xiaomi and LG, renders differentiation around product and pricing difficult. COVID-19 has accelerated competition as consumer behaviours shift from purchasing and in-person browsing to their digital equivalents. Companies are looking to create unique personalized Key trends: experiences that optimize every stage of the customer journey across each interaction, be it in-store, or via a Increased demand in website, a mobile app, social media, smartphones, or the emerging markets e-mail, to deliver the right experiences at the right Growing dominance time. Done well, enriched customer experiences will enable businesses in the consumer electronics of Asian companies industry to build customer loyalty in driving Convergence of sustainable competitive advantage in the long-term. technologies, devices and industries ¹ Consumer Electronics Market Size, Global Market Insights Key trends shaping the future Localization drives conversions As consumer electronics giants such as Xiaomi, Huawei, and Samsung compete for market shares in new geographies, a nuanced approach is crucial for building a strong brand presence across diverse markets. -

The Evolving Electronics Industry Courting the Customer Through Insight and Innovation

Smarter electronics Point of view The evolving electronics industry Courting the customer through insight and innovation Transistor by transistor, the electronics industry is literally changing the world. Consider this: today’s fastest computer can now achieve 17 quadril- lion calculations per second1, and by 2015 there will be more than seven billion mobile devices in the world consuming and generating massive amounts of data.2 Right now there are more than one billion transistors for each person on the planet.3 With innovations like these, it is no surprise that the electronics industry continues to be a leader in research and development investment across the world.4 However, despite an impressive track record of pioneering technology, today’s electronics industry is in a state of disruption. Product life-cycles are compressing, emphasizing the need to create innovative products and services faster and more cheaply than ever before. Competitive pressures are at an all-time high, with aggressive new entrants vying with a continuing need to contain operational costs. And though profit margins for some electronics segments remain relatively high, most are under heavy margin pressure. Together, these trends are driving electronics companies to find new growth opportunities. Many believe that the best way to do this—perhaps the only way to do it—is to transform their business models by getting closer to their customers. In fact, the 2012 IBM CEO study revealed that 86 percent of global electronics CEOs are implementing extensive changes in their organizations to deepen their understanding of individual customer needs, while enabling faster, more relevant responses to markets and individuals.5 CEOs realize that innovative products and services are only successful when they deliver on customer needs. -

Modern Challenges in the Electronics Industry

Volumen 41 • No. 19 • Año 2020 • Art. 19 Recibido: 12/02/20 • Aprobado: 14/05/2020 • Publicado: 28/05/2020 Modern challenges in the electronics industry Desafíos modernos en la industria electrónica GAVLOVSKAYA, Galina V. 1 KHAKIMOV, Azat N.2 Abstract The paper analyzes the challenges and current trends in the global electronic industry, carries out a literature review and highlights the gaps in the study of the features of the development of world radio electronics. The article gives a brief historical review of the electronic industry development, provides a characteristic of the modern world electronics market and considers the most important challenges and current trends in the development of the electronic industry. key words: Electronic industry, radio electronics, digital economy, microelectronics. Resumen El documento analiza los desafíos y las tendencias actuales en la industria electrónica mundial. Lleva a cabo una revisión de la literatura y destaca las lagunas en el estudio de las características del desarrollo de la radio electrónica mundial. El artículo ofrece una breve reseña histórica del desarrollo de la industria electrónica, proporciona una característica del mercado electrónico mundial moderno y considera los desafíos más importantes y las tendencias actuales en el desarrollo de la industria electrónica. Palabras clave: industria electrónica, electrónica de radio, economía digital, microelectrónica. 1. Introduction 1.1. Relevance of the research Electronic industry as a machine-building sector today is one of the state’s competitiveness factors in the global market, an instrument for ensuring the economic development of the state in the conditions of an unstable environment and an engine of economic growth for other sectors of industry. -

Microscopy 2

nano n my e > 1 Introducing Nanoscience to Second-level Students www.crann.tcd.ie As a Partner of Trinity College. NEATEC is authorized to use and distribute this module to Non-Profit Organizations. This project is sponsored in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant #1003574. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Science Foundation. nano in my life -7 microscopy 2 •microscopy The aim of this module is to provide students with an introduction to the methods used to observe and manipulate nanomaterials. Using a PowerPoint presentation and worksheet, students will be introduced to the wave nature of light and the limitations of the light microscope. They will also be introduced to a variety of electron and scanning probe microscopic techniques. The practical aspect of this module is designed to re-acquaint students with the preparation and viewing of a variety of samples using a light microscope; the students will then be able to compare their results to images of samples taken using CRANN's electron microscopes. Learning Outcomes In this module, students will: • Appreciate the small scale at which nanoscientists work. • Recall the parts and functions of the light microscope. • Outline the limitations of the light microscope. • Differentiate between the variety of microscopy methods used to examine nanomaterials and discuss the limitations of the individual techniques. As a Partner of Trinity College. NEATEC is authorized to use and distribute this module to Non-Profit Organizations. This project is sponsored in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant #1003574. -

Electrical Electronics Engineering Technology: Programmable Logic Controllers

Electrical Electronics Engineering Technology: Programmable Logic Controllers ABOUT THE PROGRAM This Electrical/Electronics PAY Engineering Technology: The median annual wage for Programmable Logic Controllers electrical and electronics Technology certificate is designed engineering technicians to provide students with in- was $65,260 in May 2019. depth instruction in the field of Programmable Logic Controllers JOB OUTLOOK (PLC). This program will prepare Employment of electrical students for employment in and electronics engineering the ever expanding Electrical/ technicians is projected to Electronics industry as entry- have little or no change from 2018 level programmable logic to 2028. These technicians work in controller programmers and manufacturing industries, many technicians, instrumentation of which are declining or growing technicians, field engineers, and slowly. However, growth rates will sales and marketing engineers. vary by occupational specialty. Job opportunities should be best WHAT DO ELECTRICAL ELECTRONICS TECHNICIANS DO? for applicants who have either an Electrical and electronics engineering technicians (also known as associate’s degree in electronics, programmable logic controller technicians) are mostly employed in certification, or related work manufacturing settings or in research and development. Electrical and experience. electronics engineering technicians help engineers design and develop computers, communications equipment, medical monitoring devices, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department navigational -

The Evolution of Electronic Systems Technology and Its Impact on Methods of Innovation Kevin Leahy and Dr

The Evolution of Electronic Systems Technology and its Impact on Methods of Innovation Kevin Leahy and Dr. Gary Oster Regent Global Business Review 8 regent.edu/rgbr Innovation is the creative development of a specific in new products, materials, computer-aided design product, service, idea, environment, or process with tools, and manufacturing processes. With the the fundamental goal of pleasing customers and rapid expansion of semiconductor technology and extracting value from its commercialization (Rogers, electronics packaging technology, entirely new design 2003; Oster, 2011). Purposeful differentiation and manufacturing disciplines also have evolved. must continue apace to avoid being overtaken by This has changed the nature and focus of innovation, historically known competitors, as well as those who significantly increasing the diversity of design teams have yet to appear on corporate radar (Hamel, 2002). and the need for collaboration across technical and If the rate of change outside the organization exceeds business disciplines. that inside the company, survival is highly unlikely (Slater, 2004). In this decade, failure to address The Historical Evolution of Electronics environmental pressures has caused thousands of companies to slash product development programs, and the Impact on Innovation reduce the size of the workforce, merge with other From the first patent issued to Alexander Graham companies, or close down entirely. To survive and Bell for the Telegraphy in 1876 (Inventors Hall thrive in the hyper-competitive global -

Electronics Postsecondary Electronics Career Pathway Completers

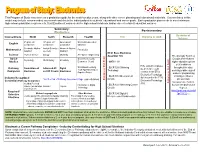

This Program of Study may serve as a graduation guide for the next four plus years, along with other career planning and educational materials. Courses listed in this model may include recommended coursework and should be individualized to students’ educational and career goals. Each graduation plan needs to meet minimum high school graduation requirements. Dual Enrollment courses can be high school academic and/or career technical education courses. Secondary: Postsecondary Electronics Bachelor of Course/Grade Ninth Tenth Eleventh Twelfth TCC Diploma or AAS Science 9th grade Lit/ 10th grade Lit/ American Lit/ World Lit/Composition / English Composition Composition Composition British Lit Coordinate Algebra / Analytic Geometry / Advanced Algebra / Mathematics Pre-calculus Algebra I Geometry Algebra II BE 41 Basic Electronics Science Physical Science Biology Chemistry AP Physics - Engineering Assembler TCC The University System of Social Government (½ unit) Georgia offers students’ Psychology World History US History Studies Economics (½ unit) - MATH 1111 higher education options at 30 institutions If the student completes Work-Based Learning, - ELCR 1005 Soldering throughout the state, Pathway Foundations of Advanced AC Digital BE 41 he/she could Youth Apprenticeship, or Technology providing a wide range of Completer Electronics and DC Circuits Electronics continue to the ET14 Capstone Project academic programming Electronics Technology - ELCR 1010 Direct Current including certificates Industry Recognized diploma and to the ET13 Visit the End of Pathway Assessment Page (see note below) Entrance Point or Exit Circuits and associate, Credential (Pathway Completer) Electronics Technology baccalaureate, masters, Health & Personal AAS. Entrance Point or Exit Introduction to Digital - ELCR 1020 Alternating Current doctoral and professional Fitness (can be taken Spanish I Physics Technology in grades 9-12) Circuits degrees. -

Electronics and Electrical Engineering Laboratory

NISTR 7568 Programs, Activities, and Accomplishments March 2009 NISTIR 7568 ELECTRONICS AND ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING LABORATORY U.S. Department of Commerce Gary Locke, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology March 2009 Patrick D. Gallagher, Deputy Director INDEX Electronics and Electrical Engineering Laboratory at a Glance . 6 Director’s Message . 7 EEEL Strategic Technical Area: Energy . 8 EEEL Strategic Technical Area: Bioelectronics . 9 EEEL Strategic Technical Area: Nanotechnology. 10 EEEL Strategic Technical Area: Spintronics. 11 EEEL Strategic Technical Area: Homeland Security . 12 Office of Law Enforcement Standards . 14 Office of Microelectronics Programs . 16 Semiconductor Electronics Division . 19 Power Device and Thermal Metrology . 20 Micro-Nano-Technology (MNT) . 22 Nanobiotechnology . 24 CMOS Device and Reliability . 26 Macro Electronics . 28 Nanoelectronic Device Metrology. 30 Infrastructure for Integrated Electronics Design and Manufacturing . 32 Knowledge Facilitation . 34 Optoelectronics Division. 37 Display Metrology . 38 Laser Radiometry. 40 High-Speed Measurements. 42 Fiber Sources and Applications . 44 Quantum Information and Terahertz Technology . 46 Nanostructure Fabrication and Metrology . 48 Semiconductor Growth and Devices. 50 Optical Materials Metrology . 52 Quantum Electrical Metrology Division . 55 Quantum Voltage System Development and Dissemination . 56 Metrology of the Ohm . 58 Quantum Conductance/Graphene-Based Quantum Metrology . 60 AC-DC Difference . 62 Farad and Impedance Metrology . 64 Electronic Kilogram . 66 Electric Power Metrology and the Smart Grid . 68 Quantum Sensors. 70 Quantum Information and Measurements . 72 Quantum Magnetic Sensors and Materials. 74 Electromagnetics Division. 77 This document describes Advanced High Frequency Devices . 78 the technical programs of the Advanced Materials Metrology. 80 Fundamental Guided-Wave Metrology . 82 laboratory. Antenna Metrology. 84 Field Parameter Metrology . -

Sales Structure Development for Consumer Electronics Retail Chains in Albania

International Journal of Business Marketing and Management (IJBMM) Volume 3 Issue 6 June 2018, P.P. 10-14 ISSN: 2456-4559 www.ijbmm.com Sales Structure Development for Consumer Electronics Retail Chains in Albania Sokol Luzi1 1(PhD Candidate, Faculty of Economics/ University of Tirana, Albania) ABSTRACT: The study investigates how sales structures of consumer electronics chains has developed in Albania during the recent years. A case study research method applies to generate understanding of the main sales channel used, taking in consideration the periods of developing of these sales channels and how these channels combine with each other. The study provided information in two main sections including an overview of the main consumer electronics chains in Albania and their sales structure, how their customers use this sales structure. The case study results mentioned that consumer electronics retailers in Albania are just now developing online sales. Results showed that customers use online channel only to get information and transactions closes in the physical store. Main implications of this study relates to creating an omni-channel structure, in order to make the boundaries between sales structures less visible to the end consumer. Through this approach retailer will have the opportunity to communicate the same concept by using more sales channel to reach their customers. KEYWORDS: Online Sales; Omni-Channel; Retail I. Introduction Consumer Electronics is one of the most developed sales structure in Albania. This retail industry has been present in Albania since the fall of communism regime, mostly through the usage of wholesale channels and warehouses. This situation was present until 1993, where the first consumer electronics shops opened in Tirana. -

Instruments to Measure Electricity: Industry's Productivity Growth Rises

Instruments to measure electricity: industry's productivity growth rises Growth in labor productivity has been spurred by the spread of automated production machinery and increased use of integrated circuits in instruments; nonproduction workers- professional and technical-are a growing proportion of industry employment BARBARA BINGHAM Output per employee hour in the manufacture of instruments of nearly 11 percent was accompanied by an employee-hour for measuring electricity-such as oscilloscopes, and volt- rise of 12 percent, so productivity decreased slightly . age and watt-hour meters-rose at an average annual rate The exception to this pattern occurred in 1975, a recession of 2.4 percent between 1972 and 1981, compared with a year. Productivity rose by more than 4 percent, chiefly be- 1 .9-percent annual rate for all manufacturing. Both output cause of a steep drop in hours which was associated with and hours increased substantially over the period-output a somewhat lesser drop in output. at 8 .6 percent a year, employee hours at 6.0 percent.' The advance in labor productivity was partially associated Strong output growth with the diffusion of automated production machinery, par- With the exception of 1974-75, output increased every ticularly,in wiring and for installing integrated circuitry in year from 1972 to 1981 . Six of the years studied showed measuring instruments. The growing use of small- and large- double-digit percentage increases. The rate of output growth scale integrated circuits in electronic instruments was also was especially strong from 1975 to 1980 . The modest in- a factor that spurred productivity improvement. crease of 2 .4 percent in 1981 reflects the 1980 economic Year-to-year movements in output per hour deviated con- slowdown. -

The Electronics Industry in Southern California: Growth and Spatial Development from 1945 to 1989* I I

THE ELECTRONICS INDUSTRY IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA: GROWTH AND SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FROM 1945 TO 1989* I I ) Allen J. Scott and Mark H. Drayse** I I I Introduction The Origins of the Electronics Industry in Southern California In this paper we provide a broad empirical descrip tion of the growth and locational structure of the electronics In the pre-World War 2 years, electronics manufac industry in Southern California. The paper is a companion turing in Southern California was largely confined to a piece to a recent study of the aircraft and parts industry in small radio industry in Los Angeles serving the local the same region (Scott and Mattingly, 1989). Together, market. Unlike places such as Berlin, Boston, London, and these two papers provide an empirical foundation for New York where electrical engineering activities flourished further investigations of the growth of high technology at this time (cf. Hall and Preston, 1988), the Lost Angeles industry in Southern California. This growth has been industry remained relatively underdeveloped. Neverthe especially stimulated by federal spending for defense less, there was in the 1920s and 1930s a growing aircraft purposes. The defense-oriented manufacturing complex industry in Los Angeles (and to a lesser extent in San that has evolved in the region in the post-War decades is Diego), and a fledgling missile industry that developed locationall y organized within a series of specialized indus over the 1940s.' These industries became the principal trial districts (or technoooles) scattered across the entire conduit through which the modem electronics industry landscape. Within these technopoles we typically find was ushered into Southern California in the 1950s and bifurcated local labor markets and intense local interlinkage 1960s. -

Electronics Industry

REDEFINING BOUNDARIES Insights from the Global C-suite Study Electronics Industry We surveyed 213 business leaders from the Electronics industry for our latest C-suite Study. So how do they differ from CxOs in other sectors? Convergence and competition Electronics CxOs overwhelmingly agree that industry convergence is the Figure 1. Electronics CxOs are particularly fearful top trend reshaping the business landscape (79 percent versus 66 percent of a land grab of our total sample). They’re excited by the new opportunities for growth this More competition expected from other industries offers, but they’re even more nervous than other CxOs about the prospect Global of outsiders invading their patch (see Figure 1). 54% 65% Electronics 1 IBM Institute for Business Value REDEFINING BOUNDARIES | Insights from the Global C-suite Study Electronics – Industry Point of View A different take on key techs Figure 2. Electronics CxOs expect technology Predictably, perhaps, Electronics CxOs say technology is by far the biggest to have a huge impact external force influencing their organizations, although market factors are another major pressure (see Figure 2). But whereas most CxOs are focusing Technology factors on cloud and mobile, Electronics CxOs are more bullish about the Internet 72% of Things. They also have much higher hopes of advanced manufacturing 90% technologies and new energy sources and solutions than their peers in Market factors other industries (see Figure 3). 71% 75% Figure 3. Electronics CxOs are really bullish about the Internet of Things Regulatory concerns 55% 19% Macro-economic factors 51% 56% People skills 48% 53% 63% 61% 57% 37% 28% 23% 12% 10% Global 62% 52% 68% 21% 45% 31% 6% 8% Electronics Cloud Mobile Internet of Cognitive Advanced New energy Bio- Man- computing solutions Things (IoT) computing manufac- sources and engineering machine and turing solutions hybrids services technologies 2 IBM Institute for Business Value REDEFINING BOUNDARIES | Insights from the Global C-suite Study Electronics – Industry Point of View Major overhaul Figure 4.