The Case of Office Development in Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

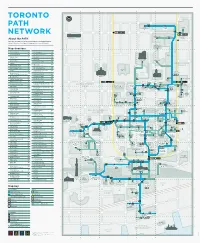

PATH Underground Walkway

PATH Marker Signs ranging from Index T V free-standing outdoor A I The Fairmont Royal York Hotel VIA Rail Canada H-19 pylons to door decals Adelaide Place G-12 InterContinental Toronto Centre H-18 Victory Building (80 Richmond 1 Adelaide East N-12 Hotel D-19 The Hudson’s Bay Company L-10 St. West) I-10 identify entrances 11 Adelaide West L-12 The Lanes I-11 W to the walkway. 105 Adelaide West I-13 K The Ritz-Carlton Hotel C-16 WaterPark Place J-22 130 Adelaide West H-12 1 King West M-15 Thomson Building J-10 95 Wellington West H-16 Air Canada Centre J-20 4 King West M-14 Toronto Coach Terminal J-5 100 Wellington West (Canadian In many elevators there is Allen Lambert Galleria 11 King West M-15 Toronto-Dominion Bank Pavilion Pacific Tower) H-16 a small PATH logo (Brookfield Place) L-17 130 King West H-14 J-14 200 Wellington West C-16 Atrium on Bay L-5 145 King West F-14 Toronto-Dominion Bank Tower mounted beside the Aura M-2 200 King West E-14 I-16 Y button for the floor 225 King West C-14 Toronto-Dominion Centre J-15 Yonge-Dundas Square N-6 B King Subway Station N-14 TD Canada Trust Tower K-18 Yonge Richmond Centre N-10 leading to the walkway. Bank of Nova Scotia K-13 TD North Tower I-14 100 Yonge M-13 Bay Adelaide Centre K-12 L TD South Tower I-16 104 Yonge M-13 Bay East Teamway K-19 25 Lower Simcoe E-20 TD West Tower (100 Wellington 110 Yonge M-12 Next Destination 10-20 Bay J-22 West) H-16 444 Yonge M-2 PATH directional signs tell 220 Bay J-16 M 25 York H-19 390 Bay (Munich Re Centre) Maple Leaf Square H-20 U 150 York G-12 you which building you’re You are in: J-10 MetroCentre B-14 Union Station J-18 York Centre (16 York St.) G-20 in and the next building Hudson’s Bay Company 777 Bay K-1 Metro Hall B-15 Union Subway Station J-18 York East Teamway H-19 Bay Wellington Tower K-16 Metro Toronto Convention Centre you’ll be entering. -

Section Ii Geographical List / Liste Géographique 1

SECTION II GEOGRAPHICAL LIST / LISTE GÉOGRAPHIQUE 1 Routing Numbers / Numéros d'acheminement Electronic Paper(MICR) Électronique Papier(MICR) Postal Address - Addresse postale 100 MILE HOUSE, BC 000108270 08270-001 BANK OF MONTREAL Cariboo Mall, P.O. Box 10, 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 001000550 00550-010 CANADIAN IMPERIAL BANK OF COMMERCE 100 Mile House Banking Centre, 1-325 Birch Ave, Box 98, 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 000304120 04120-003 ROYAL BANK OF CANADA 100 Mile House Branch, 200 Birch Ave-PO Box 700, 200 Birch Ave, 100 Mile House, BC V0K 2E0 ABBEY, SK 000300118 00778-003 ROYAL BANK OF CANADA Abbey Branch, Wayne & Cathedral, c/o 120 Centre St, Abbey, SK S0N 0A0 (Sub to 00778) ABBOTSFORD, BC 000107090 07090-001 BANK OF MONTREAL Abbotsford Main, 101-32988 South Fraser Way, Abbotsford, BC V2S 2A8 000107490 07490-001 Highstreet Branch, 3122 Mt.Leham Rd, Abbotsford, BC V2T 0C5 000120660 20660-001 Lower Sumas Mountain, 1920 North Parallell Road, Abbotsford, BC V3G 2C6 000200240 00240-002 THE BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA Abbotsford, #100-2777 Gladwin Road, Abbotsford, BC V2T 4V1 (Sub to 11460) 000211460 11460-002 Clearbrook, PO Box 2151, Clearbrook Station, Abbotsford, BC V2T 3X8 000280960 80960-002 Ellwood Centre, #1-31205 Maclure Road, Abbotsford, BC V2T 5E5 (Sub to 11460) 000251680 51680-002 Glenn Mountain Village, Unit 106 2618 McMillan Road, Abbotsford, BC V3G 1C4 001000420 00420-010 CANADIAN IMPERIAL BANK OF COMMERCE Abbotsford, 2420 McCallum Rd, Abbotsford, BC V2S 6R9 (Sub to 08820) 001001720 01720-010 McCallum Centre, Box 188, Abbotsford, -

Major Offices

Major Offices The following is contact information for Sun Life’s major offices and affiliates around the world. For inquiries and customer service, please contact the appropriate office in your area. Sun Life Financial Inc. Hong Kong, SAR Sun Life Grepa Corporate Office Sun Life Hong Kong Limited 6/F Grepalife Building 1 York Street 16/F, Cheung Kei Center Tower A, 221 Sen. Gil J. Puyat Avenue Toronto, Ontario No. 18 Hung Luen Road, Makati City 1203 Canada M5J 0B6 Hunghom, Philippines Website: sunlife.com Kowloon, Hong Kong Tel: (632) 8866-6800, 8849-9633 Tel: (852) 2103-8888 Website: sunlifegrepa.com Sun Life Canada Clients: (852) 2103-8928 Website: sunlife.com.hk Vietnam Canadian Headquarters Sun Life Vietnam Insurance Company Limited 227 King Street South India Vietcombank Tower, 29th Floor Waterloo, Ontario Birla Sun Life Insurance 5 Me Linh Square, District 1 Canada N2J 4C5 Company Limited Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Tel: 519-888-2290 One India Bulls Centre, Tower 1 Tel: (848) 6298-5888 Clients: 1-877-SUN-LIFE / 16th Floor Website: sunlife.com.vn 1-877-786-5433 Jupiter Mill Compound Website: sunlife.ca 841, Senapati Bapat Marg MFS Investment Management Elphinstone Road Montreal Office 111 Huntington Avenue Mumbai, India 400 013 Boston, Massachusetts 1155 Metcalfe Street Tel: 1-800-270-7000 in India Montreal, Quebec USA 02199 91-22-6723-9100 outside India Tel: 617-954-5000 Canada H3B 2V9 Website: birlasunlife.com Tel: 514-866-6411 Toll-free in Canada and U.S.: Website: sunlife.ca 1-800-343-2829 Birla Sun Life Asset Management Website: mfs.com Company Limited Sun Life U.S. -

PATH Network

A B C D E F G Ryerson TORONTO University 1 1 PATH Toronto Atrium 10 Dundas Coach Terminal on Bay East DUNDAS ST W St Patrick DUNDAS ST W NETWORK Dundas Ted Rogers School One Dundas Art Gallery of Ontario of Management West Yonge-Dundas About the PATH Square 2 2 Welcome to the PATH — Toronto’s Downtown Underground Pedestrian Walkway UNIVERSITY AVE linking 30 kilometres of underground shopping, services and entertainment ST PATRICK ST BEVERLEY ST BEVERLEY ST M M c c CAUL ST CAUL ST Toronto Marriott Downtown Eaton VICTORIA ST Centre YONGE ST BAY ST Map directory BAY ST A 11 Adelaide West F6 One King West G7 130 Adelaide West D5 One Queen Street East G4 Eaton Tower Adelaide Place C5 One York D11 150 York St P PwC Tower D10 3 Toronto 3 Atrium on Bay F1 City Hall 483 Bay Street Q 2 Queen Street East G4 B 222 Bay E7 R RBC Centre B8 DOWNTOWN Bay Adelaide Centre F5 155 Wellington St W YONGE Bay Wellington Tower F8 RBC WaterPark Place E11 Osgoode UNIVERSITY AVE 483 Bay Richmond-Adelaide Centre D5 UNIVERSITY AVE Hall F3 BAY ST 120 Adelaide St W BAY ST CF Toronto Bremner Tower / C10 Nathan Eaton Centre Southcore Financial Centre (SFC) 85 Richmond West E5 Phillips Canada Life Square Brookfield Place F8 111 Richmond West D5 Building 4 Old City Hall 4 2 Queen Street East C Cadillac Fairview Tower F4 Roy Thomson Hall B7 Cadillac Fairview Royal Bank Building F6 Tower CBC Broadcast Centre A8 QUEEN ST W Osgoode QUEEN ST W Thomson Queen Building Simpson Tower CF Toronto Eaton Centre F4 Royal Bank Plaza North Tower E8 QUEEN STREET One Queen 200 Bay St Four -

Corporate Report

Corporate Clerk’s Files Originator’s CD.06.VIS Files Report DATE: April 25, 2006 TO: Chair and Members of Planning and Development Committee Meeting Date: May 15, 2006 FROM: Edward R. Sajecki Commissioner of Planning and Building SUBJECT: Options for Introducing a Visitor Parking Standard for Residential Apartment Development in City Centre RECOMMENDATION: 1. That the report titled “Options for Introducing a Visitor Parking Standard for Residential Apartment Development in City Centre” dated April 25, 2006, from the Commissioner of Planning and Building, be circulated to all landowners, including condominium corporations within the City Centre Planning District, the Urban Development Institute (Peel Chapter) and the Greater Toronto Home Builders’ Association for review and comment by June 30, 2006. 2. That a public meeting be held at the Planning and Development Committee to consider the options contained in the report titled “Options for Introducing a Visitor Parking Standard for Residential Apartment Development in City Centre” dated April 25, 2006, from the Commissioner of Planning and Building. BACKGROUND: In January of 2001, City Council enacted and passed by-laws to adopt new City Centre District Policies (Amendment 20) and a district-wide City Centre Zoning By-law (By-law 0005-2001). In addition, City Centre Urban Design Guidelines were endorsed. One of the overriding goals for City Centre was to create a planning framework which would promote a distinctive, predominately urban Planning and Development Committee - 2 - CD.06.VIS April 25, 2006 character and identity for Mississauga’s City Centre. To achieve these goals, policies which assisted in opening up and promoting new development, attaining transit-supportive development densities, and realizing pedestrian-friendly, active streetscapes were recommended by the Planning and Building Department and approved by City Council. -

Self Guided Tour

The Toronto Ghosts & Hauntings Research Society Present s… About This Document: Since early October of 1997, The Toronto Ghosts and Hauntings Research Society has been collecting Toronto’s ghostly legends and lore for our website and sharing the information with anyone with an interest in things that go bump in the night… or day… or any time, really. If it’s ghostly in nature, we try to stay on top of it. One of the more popular things for a person with a passion for all things spooky is to do a “ghost tour”… which is something that our group has never really offered and never planned to do… but it is something we get countless requests about especially during the Hallowe’en season. Although we appreciate and understand the value of a good guided ghost tour for both the theatrical qualities and for a fun story telling time and as such, we are happy to send people in Toronto to Richard Fiennes-Clinton at Muddy York Walking Tours (who offers the more theatrical tours focusing on ghosts and history, see Image Above Courtesy of Toronto Tourism www.muddyyorktours.com) We do also understand that at Hallowe’en, these types of tours can Self Guided Walking Tour of fill up quickly and leave people in the lurch. Also, there are people that cannot make time for these tours because of scheduling or other commitments. Another element to consider is that we know there are Downtown Toronto people out there who appreciate a more “DIY” (do it yourself) flavour for things… so we have developed this booklet… This is a “DIY” ghost tour… self guided… from Union Station to Bloor Street…. -

Integrating Transportation and Land Use Planning at the Metropolitan Level in North America 185

Integrating transportation and land use planning at the metropolitan level in North America: multilevel governance in Toronto and Chicago Integrando o planejamento de transporte e de uso do solo em escala metropolitana na América do Norte: governança multinível em Toronto e Chicago Fanny R. Tremblay-Racicot[a], Jean Mercier[b] Licenciado sob uma Licença Creative Commons DOI: 10.7213/urbe.06.002.SE04 ISSN 2175-3369 [a] Ph.D candidate in Urban Studies at Department of Geography and Urban Studies, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA - United States, e-mail: [email protected] [b] Ph.D in public administration (SU), professor at Université Laval, Québec, QC - Canada, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article compares the policies and processes by which transportation and land use planning are integra- ted in metropolitan Toronto, Canada, and Chicago, in the United States. Using twenty-four semi-structured interviews with key informants, it describes the array of interventions undertaken by governmental and non-governmental actors in their respective domains to shed light on how the challenge of integrating trans- portation and land use planning is addressed on both sides of the border. Evidence concerning the political dynamics in Toronto and Chicago demonstrates that the capacity of metropolitan institutions to adopt and implement plans that integrate transportation with land use fundamentally depends on the leadership of the province or the state government. Although the federal government of each nation can bypass the sub-national level and intervene in local affairs by funding transportation projects that include land use components, its capacity to promote a coherent metropolitan vision is inherently limited. -

Economic Impact Analysis (2001-2009)

Waterfront Toronto Phase 1: Economic Impact Analysis (2001-2009) ` Date: June 12, 2009 Waterfront Toronto Economic Impact Analysis – Phase 1: 2001-2009 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................................ I 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. DIRECT INVESTMENT BY WATERFRONT TORONTO ......................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 EXPENDITURE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 3. ECONOMIC IMPACT APPROACH................................................................................................................................................ 12 3.1 URBANMETRICS ECONOMIC IMPACT MODEL ....................................................................................................................................... 13 3.2 QUANTITATIVE ESTIMATION OF ECONOMIC IMPACTS............................................................................................................................. 15 3.3 QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF IMPACTS AND BENEFITS................................................................................................................................17 -

Toronto Police Service Community Consultation and Volunteer Manual

1 November 2019 2 Volunteers and Community Policing The Toronto Police Service (Service) recognizes that volunteers are an integral and vital component of community policing. Service volunteers are welcomed and valued in every community, and their service to the organization is invaluable. Our volunteers serve as the first point of contact between the community and the Service. They make an impact and strengthen ties in our communities, they serve to enhance the delivery of police services, and assist in numerous community engagement initiatives and programs. The Mission Statement of the Toronto Police Service Volunteer Program is; “To create meaningful partnerships through trust, understanding, shared knowledge, effective community engagement and to maintain safety and security in our communities.” Connected by Commitment Revised November 2020 2 3 MESSAGE FROM THE TORONTO POLICE SERVICES BOARD On behalf of the Toronto Police Services Board, I would like to extend our deep and sincere appreciation to all of our volunteers for giving your time, energy, and dedication to the Toronto Police Service and to all of the communities that make up the City of Toronto. The Toronto Police Service is recognized as outstanding model in the policing community in the way in which it consults with its communities. The Board is extremely proud of this achievement and is committed to continuously working to ensure that we remain a progressive leader in this vital area. Strong and meaningful partnership with the community is an essential component of the Board’s emphasis on community policing. Indeed, The Way Forward, the Transformational Task Force’s action plan report, charts an approach to policing that is founded on embracing partnerships to create safe communities. -

Rapid Transit in Toronto Levyrapidtransit.Ca TABLE of CONTENTS

The Neptis Foundation has collaborated with Edward J. Levy to publish this history of rapid transit proposals for the City of Toronto. Given Neptis’s focus on regional issues, we have supported Levy’s work because it demon- strates clearly that regional rapid transit cannot function eff ectively without a well-designed network at the core of the region. Toronto does not yet have such a network, as you will discover through the maps and historical photographs in this interactive web-book. We hope the material will contribute to ongoing debates on the need to create such a network. This web-book would not been produced without the vital eff orts of Philippa Campsie and Brent Gilliard, who have worked with Mr. Levy over two years to organize, edit, and present the volumes of text and illustrations. 1 Rapid Transit in Toronto levyrapidtransit.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 About this Book 9 Edward J. Levy 11 A Note from the Neptis Foundation 13 Author’s Note 16 Author’s Guiding Principle: The Need for a Network 18 Executive Summary 24 PART ONE: EARLY PLANNING FOR RAPID TRANSIT 1909 – 1945 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNING OF RAPID TRANSIT PLANNING IN TORONTO 25 1.0 Summary 26 1.1 The Story Begins 29 1.2 The First Subway Proposal 32 1.3 The Jacobs & Davies Report: Prescient but Premature 34 1.4 Putting the Proposal in Context CHAPTER 2: “The Rapid Transit System of the Future” and a Look Ahead, 1911 – 1913 36 2.0 Summary 37 2.1 The Evolving Vision, 1911 40 2.2 The Arnold Report: The Subway Alternative, 1912 44 2.3 Crossing the Valley CHAPTER 3: R.C. -

401 Bay Street Toronto, On

401 BAY STREET TORONTO, ON New Availabilities: Suite 1440 - 3,785 sf Suite 1515 - 1,385 sf Suite 2104 - 7,045 sf - LEASED Suite 2704 - 2,753 sf Jordan Morrison Tim J.A. Hooton Sales Representative Sales Representative, Principal 416.673.4061 416.673.4011 [email protected] [email protected] New pedestrian bridge Metropolitan Hotel DUNDAS STREET EAST 21 ELIZABETH STREET 258 CENTRE AVENUE Marriot 277 229 CHESTNUT STREET Hotel Toronto HAGERMAN STREET Eaton SHUTER STREET Centre 220 ARMOURY ST 70 250 New City Hall 211 483 JAMES STREET 215 Bell Trinity Osgood Hall Square 401 BAY STREET OPPORTUNITY FLOOR PLANS CONTACTALBERT STREET 193 Nathan Phillips Square YONGE STREET YONGE BAY STREET BAY STREET VICTORIA STREETCHURCH Old City Hall Maritime Life 50 98 20 SUBWAY 2 BUILDING PROFILE QUEEN STREET WEST QUEEN STREET EAST 1 27 55 61 111 65 Four Seasons Sheridan 401 The LOCATION Centre for Centre Bay Performing Arts Cambridge Club 390 As a prominent part of the downtown skyline, 401 Bay Street stands 32 floors 80 20 BERTH STREET 106 50 70 76 90 100 110 tall at the intersection of Bay and Queen West, bringing together commerce, RICHMOND STREET WEST RICHMOND STREET EAST 133 121 111111 73 67 1 world class retail and municipal government. The tower is undergoing a 85 372 365 Hilton Hotel 151 complete transformation in both look and performance. All windows will be 366 357 66 56 360 replaced with high energy efficient insulated glass units. All other surfaces Richmond Adelaide Centre TEMPERANCE STREET 74 on the exterior will be covered by architectural metal panels. -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival.