The R30 Route As Potential Development Corridor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q4 F2004 F2004 RESULTS Results for the Quarter and Year Ended 30 June 2004 -Reviewed Preliminary Results

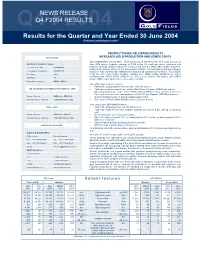

NEWS RELEASE Q4Q4 F2004 F2004 RESULTS Results for the Quarter and Year Ended 30 June 2004 -Reviewed preliminary results- RESTRUCTURING DELIVERING RESULTS INCREASED GOLD PRODUCTION AND LOWER COSTS STOCK DATA JOHANNESBURG. 29 July 2004 – Gold Fields Limited (NYSE & JSE: GFI) today announced Number of shares in issue June 2004 quarter headline earnings of R129 million (26 cents per share) compared with - at end June 2004 491,480,690 headline earnings of R221 million (45 cents per share) in the March 2004 quarter and R494 million (104 cents per share) for the June quarter of 2003. The reduction in earnings is largely - average for the quarter 491,431,716 gold price and exchange rate related and masks a solid operating performance. In US dollar Free Float 100% terms the June 2004 quarter headline earnings were US$20 million (US$0.04 per share) compared with US$32 million (US$0.07 per share) in the March 2004 quarter and US$64 ADR Ratio 1:1 million (US$0.14 per share) for the June quarter of 2003. Bloomberg / Reuters GFISJ / GFLJ.J June 2004 quarter salient features: • Attributable gold production increased to 1,042,000 ounces; JSE SECURITIES EXCHANGE SOUTH AFRICA – (GFI) • Total cash costs decreased 2 per cent to R66,218 per kilogram (US$312 per ounce); • Operating profit down 17 per cent to R545 million (US$83 million), exclusively due to a 6 per cent reduction in the rand gold price to R83,731 per kilogram (US$395 per ounce); Range - Quarter ZAR85.00 – ZAR65.02 • Organic growth projects on track in Australia and Ghana; Average Volume - Quarter 1,398,900 shares / day • Write-down of R426 million (US$62 million) at Beatrix 4 shaft. -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA Regulation Gazette No. 10177 Regulasiekoerant February Vol. 668 11 2021 No. 44146 Februarie ISSN 1682-5845 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 44146 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 44146 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 FEBRUARY 2021 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Contents Gazette Page No. No. No. GOVERNMENT NOTICES • GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS Transport, Department of / Vervoer, Departement van 82 South African National Roads Agency Limited and National Roads Act (7/1998): Huguenot, Vaal River, Great North, Tsitsikamma, South Coast, North Coast, Mariannhill, Magalies, N17 and R30/R730/R34 Toll Roads: Publication of the amounts of Toll for the different categories of motor vehicles, and the date and time from which the toll tariffs shall become payable .............................................................................................................................................. 44146 3 82 Suid-Afrikaanse Nasionale Padagentskap Beperk en Nasionale Paaie Wet (7/1998) : Hugenote, Vaalrivier, Verre Noord, Tsitsikamma, Suidkus, Noordkus, Mariannhill, Magalies, N17 en R30/R730/R34 Tolpaaie: Publisering -

Potential of the Implementation of Demand-Side Management at the Theunissen-Brandfort Pumps Feeder

POTENTIAL OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF DEMAND-SIDE MANAGEMENT AT THE THEUNISSEN-BRANDFORT PUMPS FEEDER by KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL In the Faculty of Engineering, Information & Communication Technology: School of Electrical & Computer Systems Engineering At the Central University of Technology, Free State Supervisor: Mr L Moji, MSc. (Eng) Co- supervisor: Prof. LJ Grobler, PhD (Eng), CEM BLOEMFONTEIN NOVEMBER 2006 i PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com ii DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENT WORK I, KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI, hereby declare that this research project submitted for the degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL, is my own independent work that has not been submitted before to any institution by me or anyone else as part of any qualification. Only the measured results were physically performed by TSI, under my supervision (refer to Appendix I). _______________________________ _______________________ SIGNATURE OF STUDENT DATE PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com iii Acknowledgement My interest in the energy management study concept actually started while reading Eskom’s journals and technical bulletins about efficient-energy utilisation and its importance. First of all I would like to thank ALMIGHTY GOD for making me believe in MYSELF and giving me courage throughout this study. I would also like to thank the following people for making this study possible. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and respect to both my supervisors Mr L Moji and Prof. LJ Grobler who is an expert and master of the energy utilisation concept and also for both their positive criticism and the encouragement they gave me throughout this study. -

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting Apartheid: 30 Years of Filming South Africa By Peter Davis During April 2004 and beyond we were constantly reminded that this is the tenth anniversary of the first democratic all-race elections in South Africa. I was shocked by the realization that last year also marked the thirtieth anniversary of my first visit to that country, of my first experience with apartheid. After that first trip in 1974 as part of an African tour I was doing for the American NGO, Care, I was to devote a large part of my working life to the anti-apartheid struggle. For those of us who were involved in that struggle, it was such an everyday part of life that it is hard to grasp that there is already a generation out there that does not know the meaning of “apartheid”. The struggle against apartheid took many forms, from protests, strikes, sabotage, defiance, guerrilla warfare within the country to boycotts, bans, United Nations resolutions, rock concerts, and arms and money smuggling and espionage outside. Apartheid, which was institutionalized by the coming to power of the white National Party in 1948, lasted as long as it did, against the condemnation of the world, because it had powerful friends. Chief among these were the United States, which saw a South Africa governed by whites as a useful ally in the Cold War; a Britain whose ruling class had close links with South African capital; and German, French, Israeli and Taiwanese commercial interests that extended even to sales of weapons and nuclear technology to the apartheid regime. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

General Observations About the Free State Provincial Government

A Better Life for All? Fifteen Year Review of the Free State Provincial Government Prepared for the Free State Provincial Government by the Democracy and Governance Programme (D&G) of the Human Sciences Research Council. Ivor Chipkin Joseph M Kivilu Peliwe Mnguni Geoffrey Modisha Vino Naidoo Mcebisi Ndletyana Susan Sedumedi Table of Contents General Observations about the Free State Provincial Government........................................4 Methodological Approach..........................................................................................................9 Research Limitations..........................................................................................................10 Generic Methodological Observations...............................................................................10 Understanding of the Mandate...........................................................................................10 Social attitudes survey............................................................................................................12 Sampling............................................................................................................................12 Development of Questionnaire...........................................................................................12 Data collection....................................................................................................................12 Description of the realised sample.....................................................................................12 -

The Free State, South Africa

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development THE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA The third largest of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Free State suffers from The Free State, unemployment, poverty and low skills. Only one-third of its working age adults are employed. 150 000 unemployed youth are outside of training and education. South Africa Centrally located and landlocked, the Free State lacks obvious regional assets and features a declining economy. Jaana Puukka, Patrick Dubarle, Holly McKiernan, How can the Free State develop a more inclusive labour market and education Jairam Reddy and Philip Wade. system? How can it address the long-term challenges of poverty, inequity and poor health? How can it turn the potential of its universities and FET-colleges into an active asset for regional development? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system T impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other he Free State, South Africa higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. CONTENTS Chapter 1. The Free State in context Chapter 2. Human capital and skills development in the Free State Chapter 3. -

WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association

ACLA 2017 ACLA WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome and Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................4 Welcome from Utrecht Mayor’s Office .....................................................................................6 General Information ................................................................................................................... 7 Conference Schedule ................................................................................................................. 14 Biographies of Keynote Speakers ............................................................................................ 18 Film Screening, Video Installation and VR Poetry ............................................................... 19 Pre-Conference Workshops ...................................................................................................... 21 Stream Listings ..........................................................................................................................26 Seminars in Detail (Stream A, B, C, and Split Stream) ........................................................42 Index......................................................................................................................................... 228 CFP ACLA 2018 Announcement ...........................................................................................253 Maps -

SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve

SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve South Africa AFRICA & ASIA PACIFIC | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve Season: 2021 Adult-Exclusive 10 DAYS 23 MEALS 18 SITES Experience the beauty of the people, cultures and landscapes of South Africa on this amazing Adventures by Disney vacation where you’ll thrill to the majesty of seeing wild animals in their natural environments, view Cape Town from atop the awe-inspiring Table Mountain and travel to the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of the continent. SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve Trip Overview 10 DAYS / 9 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATIONS 3 LOCATIONS Table Bay Hotel Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Pezula Hotel Game Reserve Kapama River Lodge AGES FLIGHT INFORMATION 23 MEALS Minimum Age: 6 Arrive: Cape Town (CPT) 9 Breakfasts, 8 Lunches, 6 Suggested Age: 8+ Return: Johannesburg (JNB) Dinners Adult Exclusive: Ages 18+ 3 Internal Flights Included SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve DAY 1 CAPE TOWN Activities Highlights: No Meals Included Arrive in Cape Town Table Bay Hotel Arrive at Cape Town Welkom! Upon exiting customs, be greeted by an Adventures by Disney representative who escorts you to your transfer vehicle. Relax as the driver assists with your luggage and takes you to the Table Bay Hotel. Table Bay Hotel Unwind from your journey as your Adventure Guide checks you into this spacious, sophisticated, full-service hotel located on the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront. Ask your Adventure Guide for suggestions about exploring Cape Town on your own. -

Public Libraries in the Free State

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE