Nappe and Thrust Structures in the Sparagmite Region, Southern Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linking Megathrust Earthquakes to Brittle Deformation in a Fossil Accretionary Complex

ARTICLE Received 9 Dec 2014 | Accepted 13 May 2015 | Published 24 Jun 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 OPEN Linking megathrust earthquakes to brittle deformation in a fossil accretionary complex Armin Dielforder1, Hauke Vollstaedt1,2, Torsten Vennemann3, Alfons Berger1 & Marco Herwegh1 Seismological data from recent subduction earthquakes suggest that megathrust earthquakes induce transient stress changes in the upper plate that shift accretionary wedges into an unstable state. These stress changes have, however, never been linked to geological structures preserved in fossil accretionary complexes. The importance of coseismically induced wedge failure has therefore remained largely elusive. Here we show that brittle faulting and vein formation in the palaeo-accretionary complex of the European Alps record stress changes generated by subduction-related earthquakes. Early veins formed at shallow levels by bedding-parallel shear during coseismic compression of the outer wedge. In contrast, subsequent vein formation occurred by normal faulting and extensional fracturing at deeper levels in response to coseismic extension of the inner wedge. Our study demonstrates how mineral veins can be used to reveal the dynamics of outer and inner wedges, which respond in opposite ways to megathrust earthquakes by compressional and extensional faulting, respectively. 1 Institute of Geological Sciences, University of Bern, Baltzerstrasse 1 þ 3, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 2 Center for Space and Habitability, University of Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, Bern CH-3012, Switzerland. 3 Institute of Earth Surface Dynamics, University of Lausanne, Geˆopolis 4634, Lausanne CH-1015, Switzerland. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.D. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 6:7504 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8504 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 & 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited. -

Tectonic Imbrication and Foredeep Development in the Penokean

Tectonic Imbrication and Foredeep Development in the Penokean Orogen, East-Central Minnesota An Interpretation Based on Regional Geophysics and the Results of Test-Drilling The Penokean Orogeny in Minnesota and Upper Michigan A Comparison of Structural Geology U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1904-C, D AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur rent-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Sur vey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated month ly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey, Books and Open-File Reports Section, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications of general in Books of the U.S. -

Strike and Dip Refer to the Orientation Or Attitude of a Geologic Feature. The

Name__________________________________ 89.325 – Geology for Engineers Faults, Folds, Outcrop Patterns and Geologic Maps I. Properties of Earth Materials When rocks are subjected to differential stress the resulting build-up in strain can cause deformation. Depending on the material properties the result can either be elastic deformation which can ultimately lead to the breaking of the rock material (faults) or ductile deformation which can lead to the development of folds. In this exercise we will look at the various types of deformation and how geologists use geologic maps to understand this deformation. II. Strike and Dip Strike and dip refer to the orientation or attitude of a geologic feature. The strike line of a bed, fault, or other planar feature, is a line representing the intersection of that feature with a horizontal plane. On a geologic map, this is represented with a short straight line segment oriented parallel to the strike line. Strike (or strike angle) can be given as either a quadrant compass bearing of the strike line (N25°E for example) or in terms of east or west of true north or south, a single three digit number representing the azimuth, where the lower number is usually given (where the example of N25°E would simply be 025), or the azimuth number followed by the degree sign (example of N25°E would be 025°). The dip gives the steepest angle of descent of a tilted bed or feature relative to a horizontal plane, and is given by the number (0°-90°) as well as a letter (N, S, E, W) with rough direction in which the bed is dipping. -

Introduction San Andreas Fault: an Overview

Introduction This volume is a general geology field guide to the San Andreas Fault in the San Francisco Bay Area. The first section provides a brief overview of the San Andreas Fault in context to regional California geology, the Bay Area, and earthquake history with emphasis of the section of the fault that ruptured in the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. This first section also contains information useful for discussion and making field observations associated with fault- related landforms, landslides and mass-wasting features, and the plant ecology in the study region. The second section contains field trips and recommended hikes on public lands in the Santa Cruz Mountains, along the San Mateo Coast, and at Point Reyes National Seashore. These trips provide access to the San Andreas Fault and associated faults, and to significant rock exposures and landforms in the vicinity. Note that more stops are provided in each of the sections than might be possible to visit in a day. The extra material is intended to provide optional choices to visit in a region with a wealth of natural resources, and to support discussions and provide information about additional field exploration in the Santa Cruz Mountains region. An early version of the guidebook was used in conjunction with the Pacific SEPM 2004 Fall Field Trip. Selected references provide a more technical and exhaustive overview of the fault system and geology in this field area; for instance, see USGS Professional Paper 1550-E (Wells, 2004). San Andreas Fault: An Overview The catastrophe caused by the 1906 earthquake in the San Francisco region started the study of earthquakes and California geology in earnest. -

Significance of Brittle Deformation in the Footwall

Journal of Structural Geology 64 (2014) 79e98 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Structural Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsg Significance of brittle deformation in the footwall of the Alpine Fault, New Zealand: Smithy Creek Fault zone J.-E. Lund Snee a,*,1, V.G. Toy a, K. Gessner b a Geology Department, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9016, New Zealand b Western Australian Geothermal Centre of Excellence, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia article info abstract Article history: The Smithy Creek Fault represents a rare exposure of a brittle fault zone within Australian Plate rocks that Received 28 January 2013 constitute the footwall of the Alpine Fault zone in Westland, New Zealand. Outcrop mapping and Received in revised form paleostress analysis of the Smithy Creek Fault were conducted to characterize deformation and miner- 22 May 2013 alization in the footwall of the nearby Alpine Fault, and the timing of these processes relative to the Accepted 4 June 2013 modern tectonic regime. While unfavorably oriented, the dextral oblique Smithy Creek thrust has Available online 18 June 2013 kinematics compatible with slip in the current stress regime and offsets a basement unconformity beneath Holocene glaciofluvial sediments. A greater than 100 m wide damage zone and more than 8 m Keywords: Fault zone wide, extensively fractured fault core are consistent with total displacement on the kilometer scale. e Fluid flow Based on our observations we propose that an asymmetric damage zone containing quartz carbonate Hydrofracture echloriteeepidote veins is focused in the footwall. -

The Terrane Concept and the Scandinavian Caledonides: a Synthesis

The terrane concept and the Scandinavian Caledonides: a synthesis DAVID ROBERTS Roberts , D. 1988: The terrane concept and the Scandinavian Caledonides: a synthesis. Nor. geol . unders . Bull. 413. 93-99. A revised terrane map is presented for the Scandinavian Caledcnldes. and an outline is given of the principal suspect and exot ic terranes and terrane-complexe s identified outboa rd from the Baltoscand ian miogeocline. The outermost part of the Baltoscandian continental margin is itself suspect , in the terrane sense. since the true palaeogeographical location s of rocks now represented in the Seve and serey-seuano Nappes, while inferred, are not known. The orogen -internal exotic terranes embrace the oceanic/eugeoclinal elements of the Caledonides, represented by the mag matosed imentary assemblages of the Koli Nappes, including ophiolite fragments and island arc products. Even more exot ic terranes occur in the highest parts of the tectonostratigraphy, inclu ding units which are thought possibly to derive from the Laurentian side of lapetus . D. Roberts. Norges geologiske uruierseketse, Postboks 3006. Lade, N-7002 Trondbeim , Norway . Introduction Project 233 has been to prepare a preliminary Earlier in this decade much of the research terrane map' at 1:5 M scale (Roberts et al. effort in the Caledonides of Scandinavia was 1986) for a larger, circum-Atlantic compilation. channelled through the highly successfu l IGCP This map, much simplified, is really one of Project 27 The Caledonide Orogen ' (Gee & palaeo-environments (marginal basins, vol Sturt 1985). An important aspect of the collabo canic arc comp lexes, overstep sequences , rative work in this project was that of map etc.), and not of terranes in the true sense. -

Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and Northern Oman Mountains: from Ophiolite Obduction to Continental Collision

GeoArabia, 2014, v. 19, no. 2, p. 135-174 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain Tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula and northern Oman Mountains: From ophiolite obduction to continental collision Michael P. Searle, Alan G. Cherry, Mohammed Y. Ali and David J.W. Cooper ABSTRACT The tectonics of the Musandam Peninsula in northern Oman shows a transition between the Late Cretaceous ophiolite emplacement related tectonics recorded along the Oman Mountains and Dibba Zone to the SE and the Late Cenozoic continent-continent collision tectonics along the Zagros Mountains in Iran to the northwest. Three stages in the continental collision process have been recognized. Stage one involves the emplacement of the Semail Ophiolite from NE to SW onto the Mid-Permian–Mesozoic passive continental margin of Arabia. The Semail Ophiolite shows a lower ocean ridge axis suite of gabbros, tonalites, trondhjemites and lavas (Geotimes V1 unit) dated by U-Pb zircon between 96.4–95.4 Ma overlain by a post-ridge suite including island-arc related volcanics including boninites formed between 95.4–94.7 Ma (Lasail, V2 unit). The ophiolite obduction process began at 96 Ma with subduction of Triassic–Jurassic oceanic crust to depths of > 40 km to form the amphibolite/granulite facies metamorphic sole along an ENE- dipping subduction zone. U-Pb ages of partial melts in the sole amphibolites (95.6– 94.5 Ma) overlap precisely in age with the ophiolite crustal sequence, implying that subduction was occurring at the same time as the ophiolite was forming. The ophiolite, together with the underlying Haybi and Hawasina thrust sheets, were thrust southwest on top of the Permian–Mesozoic shelf carbonate sequence during the Late Cenomanian–Campanian. -

Faults and Joints

133 JOINTS Joints (also termed extensional fractures) are planes of separation on which no or undetectable shear displacement has taken place. The two walls of the resulting tiny opening typically remain in tight (matching) contact. Joints may result from regional tectonics (i.e. the compressive stresses in front of a mountain belt), folding (due to curvature of bedding), faulting, or internal stress release during uplift or cooling. They often form under high fluid pressure (i.e. low effective stress), perpendicular to the smallest principal stress. The aperture of a joint is the space between its two walls measured perpendicularly to the mean plane. Apertures can be open (resulting in permeability enhancement) or occluded by mineral cement (resulting in permeability reduction). A joint with a large aperture (> few mm) is a fissure. The mechanical layer thickness of the deforming rock controls joint growth. If present in sufficient number, open joints may provide adequate porosity and permeability such that an otherwise impermeable rock may become a productive fractured reservoir. In quarrying, the largest block size depends on joint frequency; abundant fractures are desirable for quarrying crushed rock and gravel. Joint sets and systems Joints are ubiquitous features of rock exposures and often form families of straight to curviplanar fractures typically perpendicular to the layer boundaries in sedimentary rocks. A set is a group of joints with similar orientation and morphology. Several sets usually occur at the same place with no apparent interaction, giving exposures a blocky or fragmented appearance. Two or more sets of joints present together in an exposure compose a joint system. -

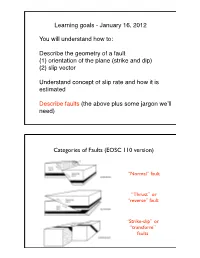

Describe the Geometry of a Fault (1) Orientation of the Plane (Strike and Dip) (2) Slip Vector

Learning goals - January 16, 2012 You will understand how to: Describe the geometry of a fault (1) orientation of the plane (strike and dip) (2) slip vector Understand concept of slip rate and how it is estimated Describe faults (the above plus some jargon weʼll need) Categories of Faults (EOSC 110 version) “Normal” fault “Thrust” or “reverse” fault “Strike-slip” or “transform” faults Two kinds of strike-slip faults Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) Stand with your feet on either side of the fault. Which side comes toward you when the fault slips? Another way to tell: stand on one side of the fault looking toward it. Which way does the block on the other side move? Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) 1992 M 7.4 Landers, California Earthquake rupture (SCEC) Describing the fault geometry: fault plane orientation How do you usually describe a plane (with lines)? In geology, we choose these two lines to be: • strike • dip strike dip • strike is the azimuth of the line where the fault plane intersects the horizontal plane. Measured clockwise from N. • dip is the angle with respect to the horizontal of the line of steepest descent (perpendic. to strike) (a ball would roll down it). strike “60°” dip “30° (to the SE)” Profile view, as often shown on block diagrams strike 30° “hanging wall” “footwall” 0° N Map view Profile view 90° W E 270° S 180° Strike? Dip? 45° 45° Map view Profile view Strike? Dip? 0° 135° Indicating direction of slip quantitatively: the slip vector footwall • let’s define the slip direction (vector) -

2019 Structural Geology Syllabus

GEOL 3411: STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY, SPRING 2021, REVISED 4/3/2021 MWF 9:00 – 9:50, Lab: T 2:00 – 4:50 Professor: Dr. Joe Satterfield Office: VIN 122 Office phone: 325-486-6766 Physics and Geosciences Department Office: 325-942-2242 E-mail: [email protected] Course Description A study of ways rocks and continents deform by faulting and folding, methods of picturing geologic structures in three dimensions, and causes of deformation. Includes a weekend field trip project (tentative date: April 15). Prerequisite: Physical Geology or Historical Geology Course Delivery Style: On-campus class and lab Structural Geology lecture and lab will be run as face-to-face classes in Vincent 146. Each person will sit at their own table to maintain social distancing. You will sit at the same table each class. Short videos made by your professor coupled with required reading in our two textbooks will introduce terms and basic concepts. We will spend much time in class and lab applying terms and concepts to solve problems. Most Fridays we will meet outside for a review discussion followed by a short quiz. Please refer to this Health and Safety web page1 for updated information about campus guidelines as they relate to the COVID-19 pandemic. Required Textbook • Structural geology of rocks and regions, Third Edition, by George H. Davis, Stephen J. Reynolds, and Charles F. Kluth. No lab manual needed! Required Lab and Field Equipment 1. Geology field book (I will place an order for all interested and pay shipping) 2. Pad of Tracing paper, 8.5 in x 11 in or 9 in x 12 in (Buy at Hobby Lobby or Michaels) 3. -

Mantle Flow Through the Northern Cordilleran Slab Window Revealed by Volcanic Geochemistry

Downloaded from geology.gsapubs.org on February 23, 2011 Mantle fl ow through the Northern Cordilleran slab window revealed by volcanic geochemistry Derek J. Thorkelson*, Julianne K. Madsen, and Christa L. Sluggett Department of Earth Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia V5A 1S6, Canada ABSTRACT 180°W 135°W 90°W 45°W 0° The Northern Cordilleran slab window formed beneath west- ern Canada concurrently with the opening of the Californian slab N 60°N window beneath the southwestern United States, beginning in Late North Oligocene–Miocene time. A database of 3530 analyses from Miocene– American Holocene volcanoes along a 3500-km-long transect, from the north- Juan Vancouver Northern de ern Cascade Arc to the Aleutian Arc, was used to investigate mantle Cordilleran Fuca conditions in the Northern Cordilleran slab window. Using geochemi- Caribbean 30°N Californian Mexico Eurasian cal ratios sensitive to tectonic affi nity, such as Nb/Zr, we show that City and typical volcanic arc compositions in the Cascade and Aleutian sys- Central African American Cocos tems (derived from subduction-hydrated mantle) are separated by an Pacific 0° extensive volcanic fi eld with intraplate compositions (derived from La Paz relatively anhydrous mantle). This chemically defi ned region of intra- South Nazca American plate volcanism is spatially coincident with a geophysical model of 30°S the Northern Cordilleran slab window. We suggest that opening of Santiago the slab window triggered upwelling of anhydrous mantle and dis- Patagonian placement of the hydrous mantle wedge, which had developed during extensive early Cenozoic arc and backarc volcanism in western Can- Scotia Antarctic Antarctic 60°S ada. -

Using CAD to Solve Structural Geology Problems

Using CAD to Solve Structural Geology Problems Introduction Computer-Aided Design software applications can be used as a much more efficient replacement for traditional manual drafting methods. So instead of using a scale, protractor, drafting pend, etc., you can instead use CAD programs to electronically draft the solution to structural geology problems, or even compose a complete geologic map or cross-section with the application. There are many CAD applications available, costing anywhere from $5,000 to $0 (free), with varying levels of sophistication. Probably the most common is AutoCAD, however, because of the high cost of this software we will instead use a free “clone” that operates (for our purposes) just as well and is very similar in operation to AutoCAD. This application is “DraftSight”, and you may download it at no cost from the below web site: http://www.3ds.com/products-services/draftsight-cad-software/free-download/ (or just “Google” the word “DraftSight”) There are versions for the MacOS and Linux operating systems, however, I have only tested the Windows version (using WIN7 and WIN10) and the Linux version. I have heard from students that have used DraftSight under MacOS successfully but I can’t verify that personally. If you wish to use CAD to solve and/or compose structural geology projects please proceed to download the install file and install it on your system. There will also are several workstations with DraftSight installed in the Earth Sciences department. Before we delve into the details of using CAD please remember this- CAD and other computer applications are just electronic replacements for manual instruments.