Responses to the Armory Show Reconsidered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recording of Marcel Duchamp’S Armory Show

Recording of Marcel Duchamp’s Armory Show Lecture, 1963 [The following is the transcript of the talk Marcel Duchamp (Fig. 1A, 1B)gave on February 17th, 1963, on the occasion of the opening ceremonies of the 50th anniversary retrospective of the 1913 Armory Show (Munson-Williams-Procter Institute, Utica, NY, February 17th – March 31st; Armory of the 69th Regiment, NY, April 6th – 28th) Mr. Richard N. Miller was in attendance that day taping the Utica lecture. Its total length is 48:08. The following transcription by Taylor M. Stapleton of this previously unknown recording is published inTout-Fait for the first time.] click to enlarge Figure 1A Marcel Duchamp in Utica at the opening of “The Armory Show-50th Anniversary Exhibition, 2/17/1963″ Figure 1B Marcel Duchamp at the entrance of the th50 anniversary exhibition of the Armory Show, NY, April 1963, Photo: Michel Sanouillet Announcer: I present to you Marcel Duchamp. (Applause) Marcel Duchamp: (aside) It’s OK now, is it? Is it done? Can you hear me? Can you hear me now? Yes, I think so. I’ll have to put my glasses on. As you all know (feedback noise). My God. (laughter.)As you all know, the Armory Show was opened on February 17th, 1913, fifty years ago, to the day (Fig. 2A, 2B). As a result of this event, it is rewarding to realize that, in these last fifty years, the United States has collected, in its private collections and its museums, probably the greatest examples of modern art in the world today. It would be interesting, like in all revivals, to compare the reactions of the two different audiences, fifty years apart. -

The Founders of the Woodstock Artists Association a Portfolio

The Founders of the Woodstock Artists Association A Portfolio Woodstock Artists Association Gallery, c. 1920s. Courtesy W.A.A. Archives. Photo: Stowall Studio. Carl Eric Lindin (1869-1942), In the Ojai, 1916. Oil on Board, 73/4 x 93/4. From the Collection of the Woodstock Library Association, gift of Judy Lund and Theodore Wassmer. Photo: Benson Caswell. Henry Lee McFee (1886- 1953), Glass Jar with Summer Squash, 1919. Oil on Canvas, 24 x 20. Woodstock Artists Association Permanent Collection, gift of Susan Braun. Photo: John Kleinhans. Andrew Dasburg (1827-1979), Adobe Village, c. 1926. Oil on Canvas, 19 ~ x 23 ~ . Private Collection. Photo: Benson Caswell. John F. Carlson (1875-1945), Autumn in the Hills, 1927. Oil on Canvas, 30 x 60. 'Geenwich Art Gallery, Greenwich, Connecticut. Photo: John Kleinhans. Frank Swift Chase (1886-1958), Catskills at Woodstock, c. 1928. Oil on Canvas, 22 ~ x 28. Morgan Anderson Consulting, N.Y.C. Photo: Benson Caswell. The Founders of the Woodstock Artists Association Tom Wolf The Woodstock Artists Association has been showing the work of artists from the Woodstock area for eighty years. At its inception, many people helped in the work involved: creating a corporation, erecting a building, and develop ing an exhibition program. But traditionally five painters are given credit for the actual founding of the organization: John Carlson, Frank Swift Chase, Andrew Dasburg, Carl Eric Lindin, and Henry Lee McFee. The practice of singling out these five from all who participated reflects their extensive activity on behalf of the project, and it descends from the writer Richard Le Gallienne. -

Société Anonyme

Société Anonyme Research Question: Modern art of the early 20th century: To what extent did the Société Anonyme contribute to the change of appreciation and perception of art? Visual Arts Extended Essay Word Count: 3,015 1 Table of Contents Title Page……………………………………………………………………….….page 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….. page 3 Representation………………………………………………………………..…page 5 Beginning of Modern Art …………………………………………………...page 6 Artistic Styles before the Société……………………………………....…page 7 Impact of Société Anonyme…………………………………………...……page 10 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………page 11 References………………………………………………………………………....page 12 Images…………………………………………………………………………….…page 14 2 Introduction The Société Anonyme was an organization created by pioneering artists Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Katherine Dreier in 1920. The goal of the society was to normalize modern art in America that was already popular in Europe and introduce American avant-garde artists, by sponsoring lectures, exhibitions, concerts, and publications. The organization collected over a thousand pieces of art, and held 80 exhibitions between 1920 and 1940. The founding members were disappointed by the lack of appreciation for modern art in America by critics and citizens and “believed it was important that the history of art be chronicled not by the historians or academics but by the artists.” (Gross) They felt responsible to give credit to all pieces and artists. This society has had a lasting effect since it first began, donating over a thousand pieces to the Yale art gallery. Marcel Duchamp, a French-American painter born in 1887, was well known for his works of cubism and Dadaism. Cubism is an early 20th century art movement where objects are portrayed in blocky, abstract ways that shows multiple viewpoints and lacks movement. -

Linking Local Resources to World History

Linking Local Resources to World History Made possible by a Georgia Humanities Council grant to the Georgia Regents University Humanities Program in partnership with the Morris Museum of Art Lesson 5: Modern Art: Cubism in Europe & America Images Included_________________________________________________________ 1. Title: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881– 1973) Date: 1907 Medium: Oil on canvas Location: Museum of Modern Art, New York 2. Title: untitled (African mask) Artist: unknown, Woyo peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo Date: c. early 20th century Medium: Wood and pigment Size: 24.5 X 13.5 X 6 inches Location: Los Angeles County Museum of Art 3. Title: untitled (African mask) Artist: Unknown, Fang Tribe, Gabon Date: c. early 20th century Medium: Wood and pigment Size: 24 inches tall Location: Private collection 4. Title: Abstraction Artist: Paul Ninas (1903–1964 Date: 1885 Medium: Oil on canvas Size: 47.5 x 61 inches Location: Morris Museum of Art 5. Title: Houses at l’Estaque Artist: Georges Braque (1882–1963) Date: 1908 Medium: Oil on Canvas Size: 28.75 x 23.75 inches Location: Museum of Fine Arts Berne Title: Two Characters Artist: Pablo Picasso (1881– 1973) Date: 1934 Medium: Oil on canvas Location: Museum of Modern Art in Rovereto Historical Background____________________________________________________ Experts debate start and end dates for “modern art,” but they all agree modernism deserves attention as a distinct era in which something identifiably new and important was under way. Most art historians peg modernism to Europe in the mid- to late- nineteenth century, with particularly important developments in France, so we’ll look at that time in Paris and then see how modernist influences affect artworks here in the American South. -

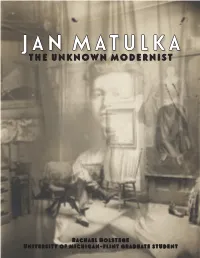

JAN MATULKA the Unknown Modernist

JAN MATULKA the unknown modernist Rachael Holstege University of michigan-flint graduate stUdent This online catalogue is published in conjunction with exhibition Jan Matulka: The Unknown Modernist presented at the Flint Institute of Arts, Flint, Michigan. Jan Matulka loans courtesy of McCormick Gallery, Chicago. Copyright © 2020 Rachael Holstege. All right reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or in any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the author. Rights and reproductions: © 2020 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (page 10) © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (page 12) © Estate of Stuart Davis / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (page 17) Cover: Double-exposed portrait of Jan Matulka, c. 1920. Jan Matulka papers, 1923-1960. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. contents PREFACE ix INTRODUCTION 5 THE YOUNG ARTIST 6 LE TYPE TRANSATLANTIQUE 8 THE NEW SPIRIT 11 LASTING LEGACY 13 ABSTRACTED CONCLUSION 16 CATALOGUE 20 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 III PREFACE I first read the name Jan Matulka while nature of art history, Matulka is continually looking through the Flint Institute of Arts forgotten. This exhibition looks to reinforce database of the nearly 9,000 artworks in his role in the pivotal decades of the their collection. Eager to find a compelling development of modern art and reinforce artist or subject to base my research on, his importance in the oeuvre of art history. I was continually drawn to two works in the collection by Czech-American artist This catalogue and accompanying exhibition Jan Matulka. -

Walt Kuhn & American Modernism

Walt Kuhn & American Modernism 80.15, Walt Kuhn (1877-1949), Floral Still Life, oil, 1920, Gift of Mrs. John D. West 89.8.2, Walt Kuhn (1877-1949), Pink Blossom, oil, 1920, Gift of Mrs. John D. West. These two paintings were created by the same artist, in the same year, and have basically the same subject matter, yet they are extremely different. Take a moment to look closely at them. How did the artist use paint to create shapes and space in each work? What is the overall emotional impact of these styles? Walt Kuhn was an artist during in the development of American Modernism: the breaking away of American artists from working in the traditional, realistic style of the academy with an emphasis on creating beauty. The new pieces began experimenting with abstraction of image: altering aspects of the subject so it looks different than to what it looks like in “real” life. Abstraction can be achieved in many ways, by using non-naturalistic color, exaggerating scale of some aspects of a subject, or by flattening the forms into two dimensional shapes and breaking the subject down into essential lines and shapes. On the left, Kuhn works in a traditional style of painting. The colors of the subject are true to life and generally depicted in a realistic style. One could argue he has been influenced a bit by the loose brushwork of the Impressionists, but overall the painting is quite traditional and depicts depth and texture one would expect from a still-life of flowers. On the right, the background has been reduced to flat areas of color. -

TAS21 Press Release Curators Announced

SEPTEMBER 9-12, 2021 JAVITS CENTER PRESS FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NEW YORK – NOVEMBER 16, 2020 THE ARMORY SHOW ANNOUNCES CURATORIAL TEAM FOR THE FAIR’S SEPTEMBER 2021 EDITION AT THE JAVITS CENTER Wassan Al-Khudhairi, Claudia Schmuckli, and Valerie Cassel Oliver will lead The Armory Show’s 2021 curatorial initiatives For its September 2021 edition, the first to be held at the state-of-the-art Javits Center, The Armory Show continues its commitment to curatorially driven programming. These initiatives—the Focus and Platform sections of the fair, as well as the Curatorial Leadership Summit—are an essential part of The Armory Show. Each one offers a unique perspective through which visitors can engage with critical issues and culturally significant themes in the context of modern and contemporary works of art. For the inaugural year at the Javits Center, Focus and Platform will join Galleries and Presents under one roof in a cohesive and integrated floorplan designed to optimize the fair experience for exhibitors and collectors alike. Wassan Al-Khudhairi, Chief Curator, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, will curate the Focus section; Claudia Schmuckli, Curator-in-Charge of Contemporary Art and Programming, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, will curate the Platform section; and Valerie Cassel Oliver, Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, will chair the Curatorial Leadership Summit. Nicole Berry, Executive Director of The Armory Show, said: For our 2021 curatorial program, we are thrilled to be collaborating with these three distinguished curators and look forward to the incredible insights and unique perspectives they’ll bring to the next edition of the Armory Show. -

John Sloan and Stuart Davis Is Gloucester: 1915-1918

JOHN SLOAN AND STUART DAVIS IS GLOUCESTER: 1915-1918 A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts by Kelly M. Suredam May, 2013 Thesis written by Kelly M. Suredam B.A., Baldwin-Wallace College, 2009 M.A., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by _____________________________, Advisor Carol Salus _____________________________, Director, School of Art Christine Havice _____________________________, Dean, College of the Arts John R. Crawford ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………..………...iii LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………….…………….iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………….xii INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER I. A BRIEF HISTORY OF GLOUCESTER……………………………………….....6 II. INFLUENCES: ROBERT HENRI, THE ASHCAN SCHOOL, AND THE MARATTA COLOR SYSTEM……………………………………………………..17 III. INFLUENCES: THE 1913 ARMORY SHOW………………………………….42 IV. JOHN SLOAN IN GLOUCESTER……………………………………………...54 V. STUART DAVIS IN GLOUCESTER……………………………………………76 VI. CONCLUSION: A LINEAGE OF AMERICAN PAINTERS IN GLOUCESTER………………………………………………………………………97 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………………..112 FIGURES…………………………………………………………………………………...118 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. John Sloan, Near Sunset, Gloucester, 1914-1915………………..………..………..……118 2. Stuart Davis, Gloucester Environs, 1915……………………………………..………….118 3. Map of Gloucester, Massachusetts………………………………………….…...............119 4. Cape Ann Map…………………………………………………………………………...119 5. Map of the Rocky -

The Armory Show - 1913

The Armory Show - 1913 Exhibition of painting and sculpture held in New York City. Of the 1,600 works assembled, one-third were European, tracing the evolution of modern art from Francisco de Goya to Picasso and Kandinsky. The show exposed the American public for the first time to advanced European art. Despite the critical turmoil, more than 500,000 people viewed the Armory Show in New York, Chicago, and Boston. American Scene Painting (1920s-50s): This is an umbrella term covering a wide range of realist painting, from the more nationalistic Regionalists (the painters of the Midwest) to the left wing Social Realists. They had in common the preference for illustrational styles and their contempt for “highbrow” European abstract. GRANT WOOD (Regionalist) American Gothic (Depict an Iowa farmer and his daughter) 1930. Oil on beaverboard, 2’ 5 7/8” x 2’ 7/8”. Art Institute of Chicago. World War II (1939 – 45) International conflict principally between the Axis Powers — Germany, Italy, and Japan — and the Allied Powers — France, Britain, the U.S., the Soviet Union, and China. In the last stages of the war, two radically new weapons were introduced: the long-range rocket and the atomic bomb. World War II was the deadliest military conflict in history. Over 60 million people were killed. It ended in 1945, leaving a new world order dominated by the U.S. and the USSR From top left: Marching German police during Anschluss, emaciated Jews in a concentration camp, Battle of Stalingrad, capture of Berlin by Soviets, Japanese troops in China, atomic -

View and Download La Belle Époque Art Timeline

Timeline of the History of La Belle Époque: The Arts 1870 The Musikverein, home to the Vienna Philharmonic, is inaugurated in Vienna on January 6. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is established on April 13, without a single work of art in its collection, without any staff, and without a gallery space. The museum would open to the public two years later, on February 20, 1872. Richard Wagner premieres his opera Die Walküre in Munich on June 26. Opening reception in the picture gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 681 Fifth Avenue; February 20, 1872. Wood engraving published in Frank Leslie’s Weekly, March 9, 1872. 1871 Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Aida premieres in Cairo, Egypt on December 24. Lewis Carroll publishes Through the Looking Glass, a sequel to his book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). James McNeill Whistler paints Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, commonly known as “Whistler’s Mother”. John Tenniel – Tweedledee and Tweedledum, illustration in Chapter 4 of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There, 1871. Source: Modern Library Classics 1872 Claude Monet paints Impression, Sunrise, credited with inspiring the name of the Impressionist movement. Jules Verne publishes Around the World in Eighty Days. Claude Monet – Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant), 1872. Oil on canvas. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. 1873 Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (Co-operative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers) (subsequently the Impressionists) is organized by Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley in response to frustration over the Paris Salon. -

An Exhibition on the Centenary of the 1913 Armory Show Andrianna Campbell and Daniel S. Palmer

DE NY/ CE DC An Exhibition on the Centenary of the NT 1913 Armory Show Andrianna Campbell E R and Daniel S. Palmer February 17-April 7, 2013 September 11-December 20, 2013 Abrons Art Center Luther W. Brady Art Gallery The Henry Street Settlement The George Washington University 466 Grand Street 805 21st Street, NW New York, New York 10002 Washington, DC 20052 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction iv David Garza, Executive Director, Henry Street Settlement Introduction v Lenore D. Miller, Director, University Art Galleries and Chief Curator Digital Art in the Modern Age 1 Robert Brennan Rethinking Decenter 2 Daniel S. Palmer Decenter: Visualizing the Cloud 8 Andrianna Campbell Nicholas O’Brien interviews Cory Arcangel, Michael Bell-Smith, James Bridle, Douglas Coupland, Jessica Eaton, Manuel Fernandez, Sara Ludy, Yoshi Sodeoka, Sara VanDerBeek, and Letha Wilson 14 Nicholas O’Brien The Story of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Armory Show 20 Charles Duncan Reprint of the Founding Document of the Abrons Arts Center 23 Winslow Carlton, President of Henry Street Settlement Artworks 24 List of Works 47 Acknowledgements 50 Published in conjunction with the exhibition: DECENTER NY/DC: An Exhibition on the Centenary of the 1913 Armory Show, Abrons Arts Center, The Henry Street Settlement February 17-April 7, 2013 and Luther W. Brady Art Gallery, The George Washington University, September 11-December 20, 2013. Catalogue designed by Alex Lesy © 2013 Luther W. Brady Art Gallery, The George Washington University. All rights reserved. No portion of this catalogue may be reproduced without the written consent of the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-935833-07-9 “Decenter” iS DEFINED AS: To cause gallery to offer an exciting and original iel S. -

Retrospective Exhibit of the Works of John Marin

101536-29 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 11 WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK TELEPHONE: CI RCLE 7-7470 FOR RELEASE Wednesday, October 21, 1936 The Museum of Modern Art* 11 West 53 Street * announces that it will open to the public on Wednesday, October 21, a retrospective exhibition of the works of John Marin, the noted American artist. The exhibition, directed by Alfred Stieg- litz, will fill the first and second floors of the Museum and will be composed of more than one hundred eighty watercolors, drawings, etchings and oils. The exhibition will be open to the public through Sunday, November 22. John Marin was born in Rutherford, New Jersey, December 23, 1870. His paternal grandfather was French; his maternal ancestors, of English descent, settled in New York and New Jersey before the Revolution. Marin attended the public schools and Stevens Institute in New Jersey. After a year at Stevens Institute he had several odd jobs, then worked for four y^ars in architectsr offices. For a short period he was a free-lance architect. From the time he was fifteen until he was nearly thirty, he made sketching tours through several eastern states, in middle western cities including Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, St, Paul, and along Lake Michigan and in the Mississippi Basin, From 1899 to 1901 Marin studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, and from 1901 to 1903 at the Art Students' League in New York, He went abroad in 1905, making Paris his headquarters. Each year thereafter un til his final return to America in 1911 he made a European trip, including in his itineraries Amsterdam, Venice, Rome, Florence, Genoa, London, Bruges, Antwerp, Brussels, Strasbourg, Nuremberg, the Belgian Coast, and the Austrian Tyrol.