And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fortnight Nears the End

World Bridge Series Championship Philadelphia Pennsylvania, USA 1st to 16th October D B 2010 aily ulletin O FFICIAL S PONSOR Co-ordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer • Chief Editor: Brent Manley • Editors: Mark Horton, Brian Senior, Phillip Alder, Barry Rigal, Jan Van Cleef • Lay Out Editor: Akis Kanaris • Photographer: Ron Tacchi Issue No. 14 Friday, 15 October 2010 FORTNIGHT NEARS THE END These are the hard-working staff members who produce all the deals — literally thousands — for the championships Players at the World Bridge Series Championships have been In the World Junior Championship, Israel and France will start at it for nearly two weeks with only one full day left. Those play today for the Ortiz-Patino Trophy, and in the World Young- who have played every day deserve credit for their stamina. sters Championship, it will be England versus Poland for the Consider the players who started on opening day of the Damiani Cup. Generali Open Pairs on Saturday nearly a week ago. If they made it to the final, which started yesterday, they will end up playing 15 sessions. Contents With three sessions to go, the Open leaders, drop-ins from the Rosenblum, are Fulvio Fantoni and Claudio Nunes. In the World Bridge Series Results . .3-5 Women’s Pairs, another pair of drop-ins, Carla Arnolds and For Those Who Like Action . .6 Bep Vriend are in front. The IMP Pairs leaders are Joao-Paulo Campos and Miguel Vil- Sting in the Tail . .10 las-Boas. ACBL President Rich DeMartino and Patrick McDe- Interview with José Damiani . .18 vitt are in the lead in the Hiron Trophy Senior Pairs. -

Team Total 1- 15 16- 30 31- 45 46- 60 1

Volume 6, Issue 7 May 2, 2012 USBF President Joan Gerard USBF “Trials” and Tribulations Vice President George Jacobs USBF Secretary Cheri Bjerkan UNITED STATES BRIDGE CHAMPIONSHIPS USBF Treasurer Sylvia Moss USBF Chief Operations Officer First Day Round of Eight... Jan Martel USBF Chief Financial Officer Barbara Nudelman Directors - USBC Chris Patrias # TEAM TOTAL 1- 16- 31- 46- Sol Weinstein 15 30 45 60 Operations Manager Ken Horwedel Appeals Administrator: 1 Nickell 95 39 28 19 9 Joan Gerard Appeals Committee: Joan Gerard, Chairman Henry Bethe 8 Spector 153 20 25 41 67 Bart Bramley Doug Daub Ron Gerard 2 Diamond 128 15 51 25 37 Robb Gordon Gail Greenberg Chip Martel Jeffrey Polisner 7 Jacobs 112 30 17 43 22 Bill Pollack Barry Rigal John Sutherlin Peggy Sutherlin 3 Fleisher 101 46 25 14 16 Howard Weinstein Adam Wildavsky VuGraph Organizers 6 Lee 121 16 21 46 38 Jan Martel Joe Stokes Bulletin Editor 4 Mahaffey 90 27 11 32 20 Suzi Subeck Webmaster Kitty Cooper 5 Milner 99 21 42 33 3 Photographer Peggy Kaplan 1 “TRIALS” AND TRIBULATIONS Nickell Frank Nickell, Capt Ralph Katz Robert Hamman Zia Mahmood Bye to Rnd of 8 Jeff Meckstroth Eric Rodwell Diamond John Diamond, Capt Brian Platnick Eric Greco Geoff Hampson Bye to Rnd of 8 Brad Moss Fred Gitelman Fleisher Martin Fleisher, Capt Michael Kamil Bobby Levin Steve Weinstein Bye to Rnd of 16 Chip Martel Lew Stansby Gordon Mark Gordon, Capt Pratap Rajadhyaksha Alan Sontag David Berkowitz Ron Rubin Matthew Granovetter Spector Warren Spector, Capt Gary Cohler Joe Grue Curtis Cheek Joel Wooldridge -

Polish Girls on Top

Bulletin 2 Friday, 13 July 2007 POLISH GIRLS ON TOP TEAM PHOTOGRAPHS Today is the turn of the following teams to have their photographs taken for the EBL database. Would the captains please ensure that all players of the team plus the npc are present outside the front door of the Palace as follows: Girls Teams Latvia 13.00 Netherlands 13.00 Norway 13.00 England 13.00 Poland 17.00 Sweden 17.00 Turkey 17.00 Palazzo del Turismo, Jesolo Maria Ploumbi - EBL Photographer Norway produced the result of the day in the Juniors when they defeat- ed defending champions, Poland, 22-8 in Round 2. The Norwegians fol- lowed that up with a 25-2 demolition of Czech Republic and led after VUGRAPH three rounds by 13 VPs. Norway have 71 VPs, ahead of Latvia on 58, MATCHES Netherlands and Sweden with 54.5 and Italy 53. The Polish Girls had a huge day. They began by getting revenge for their Junior team, crushing Norway 25-3, and followed up with 25-4 against Den- Croatia - Latvia (Juniors) 10.00 mark and 25-5 over England, giving a perfect 75 VPs out of a possible 75 Estonia - Poland (Girls) 14.00 on the day. Poland lead after four rounds with 95.5 VPs, already well ahead Sweden - Denmark (Juniors) 17.30 of Germany on 77, Italy on 71 and Netherlands on 68. 21st EUROPEAN YOUTH TEAM CHAMPIONSHIPS Jesolo, Italy JUNIOR TEAMS TODAY’S RESULTS PROGRAM ROUND 2 ROUND 4 Match IMP’s VP’s 1 TURKEY GREECE 1 SLOVAKIA GREECE 45 - 32 18 - 12 2 CROATIA LATVIA 2 SWEDEN CROATIA 50 - 57 14 - 16 3 SLOVAKIA SCOTLAND 3 ROMANIA TURKEY 32 - 91 4 - 25 4 SWEDEN AUSTRIA 4 CZECH REPUBLIC -

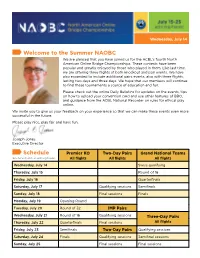

Schedule Welcome to the Summer NAOBC

Wednesday, July 14 Welcome to the Summer NAOBC We are pleased that you have joined us for the ACBL’s fourth North American Online Bridge Championships. These contests have been popular and greatly enjoyed by those who played in them. Like last time, we are offering three flights of both knockout and pair events. We have also expanded to include additional pairs events, also with three flights, lasting two days and three days. We hope that our members will continue to find these tournaments a source of education and fun. Please check out the online Daily Bulletins for updates on the events, tips on how to upload your convention card and use other features of BBO, and guidance from the ACBL National Recorder on rules for ethical play online. We invite you to give us your feedback on your experience so that we can make these events even more successful in the future. Please play nice, play fair and have fun. Joseph Jones Executive Director Schedule Premier KO Two-Day Pairs Grand National Teams See full schedule at acbl.org/naobc. All flights All flights All flights Wednesday, July 14 Swiss qualifying Thursday, July 15 Round of 16 Friday, July 16 Quarterfinals Saturday, July 17 Qualifying sessions Semifinals Sunday, July 18 Final sessions Finals Monday, July 19 Opening Round Tuesday, July 20 Round of 32 IMP Pairs Wednesday, July 21 Round of 16 Qualifying sessions Three-Day Pairs Thursday, July 22 Quarterfinals Final sessions All flights Friday, July 23 Semifinals Two-Day Pairs Qualifying sessions Saturday, July 24 Finals Qualifying sessions Semifinal sessions Sunday, July 25 Final sessions Final sessions About the Grand National Teams, Championship and Flight A The Grand National Teams is a North American Morehead was a member of the National Laws contest with all 25 ACBL districts participating. -

Cemetery Records (PDF)

Jacksonville Cemetery Records How to Search in this PDF If you are searching for a name such as Abraham Meyer, you will get no results. Search for only the first or last name. The search function will only find two or more words at once if they occur together in one cell of the spreadsheet, e.g. “Los Angeles”. On computers: For PCs, hold down the Control key, then tap the F key. For Macs, hold down the Command key, then tap the F key. A text entry box will appear either in the lower left or upper right of the PDF. Type the keyword (last name, place of birth, etc.) you wish to search for and the document will automatically scroll to the first occurrence of the word and highlight it. If it does not, press the Enter or Return key on the keyboard. To scroll the document so as to show more occurrences of the word, click on either the down/up or next/previous buttons at right of the text box. For ease of spotting the highlighted words, it’s best to zoom in on the document to about 160-180% by clicking the plus (+) or minus (-) symbols at top center of the document. On smartphones and tablets: Note: You must use the native web browser app on your device. Other browser apps, such as Firefox, may not allow searching in an open document. For Apple devices, use Safari: Type the keyword (last name, place of birth, etc.) into the URL (web address box at top of screen). -

Rebel Salvation: the Story of Confederate Pardons

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1998 Rebel Salvation: The Story of Confederate Pardons Kathleen Rosa Zebley University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Zebley, Kathleen Rosa, "Rebel Salvation: The Story of Confederate Pardons. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1998. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3629 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kathleen Rosa Zebley entitled "Rebel Salvation: The Story of Confederate Pardons." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. Paul H. Bergeron, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Stephen V. Ash, William Bruce Wheeler, John Muldowny Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kathleen Rosa Zebley entitled "Rebel Salvation: The Story of Confederate Pardons." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy, witha major in History. -

Education Packet.Pub

Pre-Visit & Post Visit Packet—House Tour/Site Tour EDUCATION PACKET Zebulon B. Vance Birthplace State Historic Site 911 Reems Creek Rd. Weaverville, North Carolina 28787 (828) 645-6706 Fax (828) 645-0936 [email protected] Pre-Visit & Post Visit Packet—House Page 2 Pre-Visit & Post Visit Packet—House Page 57 Department of Cultural Resources The North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources was formed in Zebulon B. Vance Birthplace 1971 to serve North Carolina’s citizens State Historic Site across the state in an outreach to 911 Reems Creek Rd. broaden minds and spirits, preserve Weaverville, North Carolina 28787 history and culture, and to recognize (828) 645-6706 and promote our cultural resources as an essential element of North Carolina’s economic and social well-being. It was the first state organization in the nation to include all agencies for arts and culture Welcome: under one umbrella. Thank you for your interest in the Zebulon B. Cultural Resources serves more than 19 million people annually through three major areas: The Arts, The State Library of North Carolina and Archives and His- Vance Birthplace State Historic Site. The site preserves tory. the birthplace of North Carolina’s Civil War Governor, and The North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources includes the State Library, the State Archives, 27 Historic Sites, 7 History Muse- interprets 18 th and 19 th century history through the lives ums, Historical Publications, Archaeology, Genealogy, Historic Preser- vation, the North Carolina Symphony, the North Carolina Arts Council, of Zebulon B. Vance and his family for the education of and the North Carolina Museum of Art. -

William W. Holden and the Standard-- the Civil War Years

The Woman's College of The University of North Carolina LIBRARY COLLEGE COLLECTION JANNETTFG^RfRINa^H FIORE WILLIAM W. HOLDEN AND THE STANDARD-- THE CIVIL WAR YEARS by Jannette Carringer Fiore A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Greensboro June, 1966 Approved by Director APPROVAL SHEET This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, North Carolina. Thesis Director- /^/^r?^. Oral Examination A V Committee Members (/-f ft O A 0 Date of Examination 297101 FIORE, JANNETTE CARRTNGER. William W. Hol'ien and the Stan-'ard--The Civil War Years. (1966) Directed by: Dr. Richard Bardolph. op. *2, One of the most controversial Civil War political figures in North Carolina was William W. Holden, editor of the powerful Raleiph, North Carolina Standard, member consecutively of four political parties, and reconstruction governor of North Carolina. Holden has been cenerallv re- garded as a politically ambitious and unscrupulous man, as well as some- thing of a traitor for his role as advocate of pence during the Civil War. Holden, trained in newspaper work from boyhood, left the Whig partv in 1843 to accept the editorship of the Standard, the Democratic partv organ in Raleigh. He rapidly built it into the larrest paper in the state and became a leader in the Democratic partv, and one of its more liberal voices. Originally a defender of the right of secession, his liberal position on other matters and his humble origins had led bv 1860 to his alienation from the leadership of his party, and from the slaveholding interest in North Carolina. -

'Devoted to the Interests of His Race': Black Officeholders

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: “DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF HIS RACE”: BLACK OFFICEHOLDERS AND THE POLITICAL CULTURE OF FREEDOM IN WILMINGTON, NORTH CAROLINA, 1865-1877 Thanayi Michelle Jackson, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Associate Professor Leslie S. Rowland Department of History This dissertation examines black officeholding in Wilmington, North Carolina, from emancipation in 1865 through 1876, when Democrats gained control of the state government and brought Reconstruction to an end. It considers the struggle for black office holding in the city, the black men who held office, the dynamic political culture of which they were a part, and their significance in the day-to-day lives of their constituents. Once they were enfranchised, black Wilmingtonians, who constituted a majority of the city’s population, used their voting leverage to negotiate the election of black men to public office. They did so by using Republican factionalism or what the dissertation argues was an alternative partisanship. Ultimately, it was not factional divisions, but voter suppression, gerrymandering, and constitutional revisions that made local government appointive rather than elective, Democrats at the state level chipped away at the political gains black Wilmingtonians had made. “DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF HIS RACE”: BLACK OFFICEHOLDERS AND THE POLITICAL CULTURE OF FREEDOM IN WILMINGTON, NORTH CAROLINA, 1865-1877 by Thanayi Michelle Jackson Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Advisory Committee: Associate Professor Leslie S. Rowland, Chair Associate Professor Elsa Barkley Brown Associate Professor Richard J. -

Thewestfield Leader During 1966 the Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper in Union County

DRIVE TO EXIST THEWESTFIELD LEADER DURING 1966 THE LEADING AND MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPER IN UNION COUNTY Published WESTFIELD, NBW JERSEY, THURSDAY. APRIL 21, 1966 Kvery Thursday 36 Pages—10 Cent* Move Clock Ahead Saturday Is Bundle Day Come Saturday night the Many Due At YMCA clorkwlnders ("tin remember) will move the hands one hour uhead and everyone in the fam- ily will lose an hour of sleep Sun- Monday For Annual day morning for Daylight Sav- ings Time is here again. Beginning officially at 2 a.m. Sunday morning (lie extra day- light period will stretch through Meeting, Dinner next October and provide a lin- gering twilight In tlie evenings Bobby Richar<Ine>n for everyone to enjoy—except of Due For Honor* course tired parents trying to To Be Speaker convince small fry (hut bedtime The Hoard of Education will be host at a public reception for Nearly 200 members and Kuesls has arrived desplU; (he bright- will be present at thc YMCA un- ness. Dr. and Mrs. S, N. Ewpn Jr. to- night from 8 until 10 o'clock In nual meeting Monday evening nt thc Westfield High School ciifc- which famed second baseman of the 11'riii. All who wish to honor the New York Yankees, Robert C. "Bob- District 4 Scouts Ewnns are cordially Invited to by" Itichardson will be honored attend. guest and featured speaker. Plan Recognition According to Arthur C. Fried, cluiirman, on additional 500 guests Series Of Blazes arc expected to join those attend- Dinner April 27 ing the meeting for Ml. -

2013 United States Bridge Championships

UNITED STATES BRIDGE FEDERATION CONDITIONS OF CONTEST FOR THE 2013 UNITED STATES BRIDGE CHAMPIONSHIPS Adopted by the Board of Directors of the United States Bridge Federation Board of Directors of the United States Bridge Federation George Jacobs, President Howard Weinstein, Vice-President Cheri Bjerkan, Treasurer Bob Katz Ralph Katz Sylvia Moss Jonathan Weinstein Jan Martel, C.O.O. International Team Trials Committee Henry Bethe, Chairman Howie Weinstein, Vice Chair Fred Gitelman Jan Martel Bruce Rogoff Michael Becker Robb Gordon Jeff Meckstroth Michael Rosenberg David Berkowitz Robert Hamman Dan Morse Danny Sprung Cheri Bjerkan Geoff Hampson Brad Moss Lew Stansby Peter Boyd Marty Harris Sylvia Moss John Sutherlin Drew Casen Christal Henner Nick Nickell Jonathan Weinstein Ira Chorush Uday Ivatury Barbara Nudelman Sol Weinstein Chris Compton George Jacobs Mike Passell Steve Weinstein Jason Feldman Mike Kamil Chris Patrias Roy Welland Mark Feldman Ralph Katz Bill Pollack Adam Wildavsky Marty Fleisher Steve Landen Pratap Rajadhyaksha Bobby Wolff Joan Gerard Chip Martel Eric Rodwell Kit Woolsey Communications/Liaison Technical and Advisory Committee ITTC Appeals Michael Becker Michael Becker Chip Martel Joan Gerard, Chair Cheri Bjerkan (WITTC) Henry Bethe Jan Martel John Sutherlin Jan Martel (USBF) Peter Boyd Michael Rosenberg Howard Weinstein Ira Chorush Danny Sprung Bobby Wolff Conventions Chris Compton Howard Weinstein [Selects on-site Committee] Henry Bethe Mark Feldman Jonathan Weinstein 2013 USBC Appeals Rich Colker Geoff Hampson Sol Weinstein To be determined Chip Martel Marty Harris Adam Wildavsky Kit Woolsey i 2013 USBC Conditions of Contest TABLE OF CONTENTS I. AUTHORITY AND OVERVIEW ........................................................................ 1 II. GENERAL INFORMATION .............................................................................. 1 A. Registration. ................................................................................................ 1 B. -

Italy Triumph in Clash of the Titans

Co-ordinator: Jean Paul Meyer Editor: Mark Horton Issue: 15 Ass. Editors: Brent Manley, Brian Senior Layout Editor: Stelios Hatzidakis Saturday 9, September 2000 Italy triumph in clash of the Titans In a match that will go down in history as one of the most exciting ever, it was Italy, represent- ed by Norberto Bocchi, Giorgio Duboin, Dano de Falco, Guido Ferraro, Lorenzo Lauria, Alfredo Versace, npc Carlo Mosca and coach Maria Teresa Lavazza who emerged as Champions in the Open series of the Olympiad. It was Italy's fourth win in all, and their first since1972.They now share with France the distinction of having won four times. It was only on the last few boards of the final session that they overcame the magnificent team from Poland, Cezary Balicki, Krzysztof Jassem, Michal Kwiecien, Jacek Pszczola, Piotr Tuszynski, Adam Zmudzinski, npc Jan Rogowski and coach Wojciech Siwiec. Transnational Mixed Teams In a final that was no less exciting, it was the combination from USA, Poland and Israel, WORLD TRANSNATIONAL team e-bridge, npc Pinhas Romik, Jill Meyers, MIXED TEAMS CHAMPIONSHIP Irina Levitina, Migry Tzur-Campanile, Sam Lev, John Mohan, Piotr Gawrys that captured the Final World title. They survived a tremendous fight Set 1 Set 2 Set 3 Total back by Bessis, Michel Bessis,Véronique Bessis, e-bridge 40 6 20 66 Catherine D'Ovidio, Paul Chemla, who took the Bessis 1421255 silver medal for France. PDF version, courtesy of WBF The Daily Bulletin is produced on XEROX machines and on XEROX paper www.bridge.gr +31 (0) 73 6128611 11th WORLD TEAMS BRIDGE OLYMPIAD26 August - 9 September OPEN TEAMS RESULTS FINAL Home Team Visiting Team Board 1-16 Board 17-32 Board 33-48 Board 49-64 Board 65-80 Italy Poland 35 - 8 9 - 22 37 - 31 64 - 23 26 - 60 Home Team Visiting Team Board 81-96 Board 97-112 Board 113-128 Total Italy Poland 26 - 13 36 - 57 36 - 35 269 - 249 Farewell by Laurens Hoedemaker, President of the Dutch Bridge Federation Dear Bridge Friends, At the end of the Olympiad I wish to thank you all for your presence in Maastricht.