Mustela Erminea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wetlands Australia

Wetlands Australia National wetlands update August 2014—Issue No 25 Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2014 Wetlands Australia National Wetlands Update August 2014 – Issue No 25 is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons By Attribution 3.0 Australia licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au This report should be attributed as ‘Wetlands Australia National Wetlands Update August 2015 – Issue No 25, Commonwealth of Australia 2014’ The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Cover images Front cover: Wetlands provide important habitats for waterbirds, such as this adult great egret (Ardea modesta) at Leichhardt Lagoon in Queensland (© Copyright, Brian Furby) Back cover: Inland wetlands, like Narran Lakes Nature Reserve Ramsar site in New South Wales, support high numbers of waterbird breeding and provide refuge for birds during droughts (© Copyright, Dragi Markovic) ii / Wetlands Australia August 2014 Contents Introduction to Wetlands Australia August -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Bird Vulnerability Assessments

Assessing the vulnerability of native vertebrate fauna under climate change, to inform wetland and floodplain management of the River Murray in South Australia: Bird Vulnerability Assessments Attachment (2) to the Final Report June 2011 Citation: Gonzalez, D., Scott, A. & Miles, M. (2011) Bird vulnerability assessments- Attachment (2) to ‘Assessing the vulnerability of native vertebrate fauna under climate change to inform wetland and floodplain management of the River Murray in South Australia’. Report prepared for the South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Natural Resources Management Board. For further information please contact: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Phone Information Line (08) 8204 1910, or see SA White Pages for your local Department of Environment and Natural Resources office. Online information available at: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au Permissive Licence © State of South Australia through the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. You may copy, distribute, display, download and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose subject to the conditions that you (1) attribute the Department as the copyright owner of this publication and that (2) you obtain the prior written consent of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources if you wish to modify the work or offer the publication for sale or otherwise use it or any part of it for a commercial purpose. Written requests for permission should be addressed to: Design and Production Manager Department of Environment and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 Adelaide SA 5001 Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources makes no representations and accepts no responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or fitness for any particular purpose of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of this publication. -

A Year on the Vasse-Wonnerup Wetlands

Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Department of Water and Environmental Regulation A Year on the Vasse-Wonnerup Wetlands An Ecological Snapshot March 2017—January 2018 W IN N T M E U R T U A S P R R I N E G M M U S Musk duck (Biziura lobata) (Photo: Mark Oliver) The Vasse-Wonnerup Wetlands The conservation values of the Vasse-Wonnerup wetlands are recognised on a local, state, national and international level. The wetlands provide habitat to thousands of Australian and migratory water birds as well as supporting the largest breeding population of black swans in the state. In 1990 the wetlands were recognised as a ‘Wetland of International Importance’ under the Ramsar Convention. The wetlands are also one of the most nutrient enriched wetlands in Western Australia, characterised by extensive macroalgae and phytoplankton blooms and occasional major fish kills. Poor water quality in the wetlands is a major concern for the local community. Over the past four years scientists have been working together to investigate options to improve water quality in the wetlands by monitoring seawater inflows through the Vasse surge barrier and modelling options to increase water levels and flows into the Vasse estuary. These trials have successfully shown that seawater inflows can reduce the incidence of harmful phytoplankton blooms and improve conditions for fish in the Vasse Estuary Channel over summer months. What isn’t as well understood is how these management approaches and subsequent increased water levels may impact on the broader wetland system, especially how the ecology of the wetlands responds to changes in the timing and volume of seawater inflow through the surge barriers. -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Bird Watching in Australia

Birdwatching in Australia Let’s Go Birdwatching! Practice your students’ observation skills as they learn about the Fort Wayne PROGRAM GOALS Learn about how Children’s Zoo marine animals and their habitat. Each bird will be doing Australian birds something different in their habitat, so join us and help us identify each bird’s Discuss their traits, behaviors. See below for a variety of questions to engage your student even coloration, and further: other interesting observations Can you describe how they are moving? Are they eating, nesting, or what are they doing? GRADES Are they communicating? What do they sound like? 3rd to 5th Can you describe their colors, patterns, and more? MATERIALS Have students complete the worksheet as they watch the video or observe the Pencils birds at the zoo. If at the zoo, give students five to ten minutes per animal to Clipboards create observations of their chosen birds. Have students form small groups to RECOMMENDED discuss different behaviors and characteristics of their birds. Share different facts ASSESSMENT about the listed birds from the video to the discussion. Be on the lookout for other birds’ behaviors at the zoo! Share your lessons with the Fort Wayne Grade worksheet based on Children’ Zoo. Tag #fwkidszoo or email [email protected] to express how completeness you used these supplemental activities! Assess students on appropriateness of Different Types of Birds: words used to Rainbow Lorikeet: They have a green plumage with describe birds bright red, yellow, and orange feathers on the breast, neck, and sides of the belly. Their head is often in violet blue. -

Spur-Winged Lapwing Vanellus Spinosus

Spur-winged Lapwing Vanellus spinosus Class: Aves Order: Charadriiformes Family: Charadriidae Characteristics: Also known as the spur-winged plover (not to be confused with the recently renamed masked lapwing of Australasia), this lapwing is a wading bird identified by their striking white cheek feathers, black head cap, brown wings against a black body and long black legs. Behavior: In Africa, lapwings don’t travel far outside their home area but merely make short movements to find wetter areas of their habitats. They spend Range & Habitat: their time searching the marshy ground for small invertebrates. Marshes and wetland habitats of central Africa Reproduction: Because of their large range, these birds have variable breeding seasons. Spur-winged lapwings nest in solitary monogamous pairs, often with other mixed species bird nesting colonies. The large nesting groups help protect the birds in the colonies against predation. The lapwing pair will build a nest in a scrape on the ground sometimes lined with vegetation. The female lays 2 eggs that are yellow with brownish black mottling. They hatch after a 28-day incubation period and both sexes help feed the young. If they double-clutch, the male tends the older chicks while the female incubates the second brood (Sacramento Zoo). Lifespan: over 15 years in Diet: captivity, up to 15 years in the Wild: Invertebrates wild. Zoo: softbill, feline diet, capelin, mealworms and insectivore diet Special Adaptations: Spur- Conservation: winged lapwings have a unique Spur-winged lapwings are abundant in their range in Africa and as such call that acts as an alert when are listed as Least Concern by IUCN. -

Macquarie River Bird Trail

Bird Watching Trail Guide Acknowledgements RiverSmart Australia Limited would like to thank the following for their assistance in making this trail and publication a reality. Tim and Janis Hosking, and the other members of the Dubbo Field Naturalists and Conservation Society, who assisted with technical information about the various sites, the bird list and with some of the photos. Thanks also to Jim Dutton for providing bird list details for the Burrendong Arboretum. Photographers. Photographs were kindly provided by Brian O’Leary, Neil Zoglauer, Julian Robinson, Lisa Minner, Debbie Love, Tim Hosking, Dione Carter, Dan Giselsson, Tim Ralph and Bill Phillips. This project received financial support from the Australian Bird Environment Foundation of Sacred kingfisher photo: Dan Giselsson BirdLife Australia. Thanks to Warren Shire Council, Sarah Derrett and Ashley Wielinga in particular, for their assistance in relation to the Tiger Bay site. Thanks also to Philippa Lawrence, Sprout Design and Mapping Services Australia. THE MACQuarIE RIVER TraILS First published 2014 The Macquarie valley, in the heart of NSW is one of the The preparation of this guide was coordinated by the not-for-profit organisation Riversmart State’s — and indeed Australia’s — best kept secrets, until now. Australia Ltd. Please consider making a tax deductible donation to our blue bucket fund so we can keep doing our work in the interests of healthy and sustainable rivers. Macquarie River Trails (www.rivertrails.com.au), launched in late 2011, is designed to let you explore the many attractions www.riversmart.org.au and wonders of this rich farming region, one that is blessed See outside back cover for more about our work with a vibrant river, the iconic Maquarie Marshes, friendly people and a laid back lifestyle. -

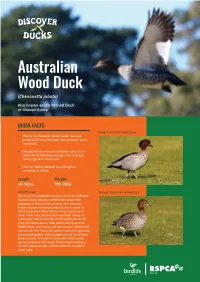

Australian Wood Duck (Chenonetta Jubata)

Australian Wood Duck (Chenonetta jubata) Also known as the ‘Maned Duck’ or ‘Maned Goose’ QUICK FACTS Male Australian Wood Duck • They are nicknamed ‘Maned Goose’ because people think they look more like miniature geese than ducks. • Wood Ducks love heavy rainfall because this is when the tastiest bugs emerge. They also love laying eggs after heavy rain. • They are better adapted to walking than swimming or diving. Length: Weight: 44–50cm 700–955g Identification: Female Australian Wood Duck The Australian Wood Ducks have earnt the nickname ‘Maned Goose’ because of their very goose-like appearance. The feathers around their neck and breast also give the impression of a lion’s mane. In flight, Australian Wood Ducks’ wings come out on show. Their wing tips are black and their wings are a pale grey with a white bar on the underside of the wing. Like many ducks, male and female Australian Wood Ducks vary in size and appearance. Males tend to have a darker head and smaller mane with speckled brown-grey bodies, a black undertail and black lower belly. Females have paler heads with white stripes above and below their eyes. Their breast and flanks are also speckled with a white undertail and white lower belly. BEHAVIOUR DISTRIBUTION & HABITAT Unlike most ducks, Australian Wood Ducks do not favour Australian Wood Ducks are found across most of Australia. swimming and will only enter open water if they’re Flocks of hundreds of birds can be found gathering disturbed. Instead, they prefer to waddle around and graze in southern areas of Australia in autumn and winter. -

Managing Bird Strike Risk Species Information Sheets

MANAGING BIRD STRIKE RISK SPECIES INFORMATION SHEETS AIRPORT PRACTICE NOTE 6 1 SILVER GULL 2 2 MASKED LAPWING 7 3 DUCK 12 4 RAPTORS 16 5 IBIS 22 6 GALAH 28 7 AUSTRALIAN MAGPIE 33 8 FERAL PIGEON 37 9 FLYING-FOX 42 10 BLACK KITE 47 11 PELICAN 50 12 MARTIN AND SWALLOW 54 13 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 58 Legislative Protection Given to Each Species 58 Land Use Planning Near Airports 59 Bird Management at Off-airport Sites 61 Managing Birds at Landfills 62 Reducing the Water Attraction 63 Grass Management 64 Reporting Wildlife Strikes 65 Using Pyrotechnics 66 Knowing When and How to Lethal Control 67 Types of Dispersal Tools 68 What is Separation-based Management 69 How to Use Data 70 Health and Safety: Handling Biological Remains 71 Getting Species Identification Right 72 Defining a Wildlife Strike 73 CONTENTS PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 2015 ii MANAGING BIRD STRIKE RISK SPECIES INFORMATION SHEETS INTRODUCTION The Australian Airports Association (AAA) commissioned These new and revised fact sheets provide airport preparation of this Airport Practice Note to provide members with useful information and data regarding 1 SILVER GULL 2 aerodrome operators with species information fact common wildlife species around Australian aerodromes sheets to assist them to manage the wildlife hazards and how best to manage these animals. The up-to-date 2 MASKED LAPWING 7 at their aerodrome. The species information fact sheets suite of species information fact sheets will provide were originally published in June 2004 by the Australian aerodrome operators with access to data, information 3 DUCK 12 Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) as Bird Information and management techniques for the species posing Fact Sheets. -

Foot-Trembling in the Spur-Winged Plover (Vanellus Miles Novaehollandiae)

Notornis, 2001, Vol. 48: 59-60 0029-4470 0The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. 2001 SHORT NOTE Foot-trembling in the spur-winged plover (Vanellus miles novaehollandiae) BRUCE R. KEELEY 13 The Glebe, Howick, Auckland 1705 millkee@ nznetgen. nz A range of distinct foot and leg movements, associated alternately It was not clear whether or not the foot made with feeding behaviour, has been described in several contact with the mud, though at times it appeared to be Palearctic-breeding charadriids, and the possible adaptive 'leg-shaking' rather than 'foot-tapping' that was involved. significance of such movements in the search and There was no obvious correlation between the foot capture of prey has been debated (Simmonds 1961a, b; movement and any subsequent capture of prey Sparks 1961). The range of movements has been broadly While, amongst the lapwings (Subfamily Mnellinae), divided into 'foot-trembling' (involving 1 leg at a time), similar behaviour is well documented in the Eurasian and 'foot-paddling' (where both feet are involved), lapwing (Cramp 1983), perusal of literature on the spur- (Simmonds 1961b). Species in which this behaviour had winged plover/masked lapwing yielded only 2 references: been observed included Eurasian lapwing (Knellus Barlow (1983), in describing elements of feeding vanellus), little ringed plover (Charadrius dubius), ringed behaviour which must be learned bv/J iuvenile ~lovers. plover (C. hiaticula), Kentish plover (C. alexandrinus), refers to 'the foot tremor, the lunge, the stab'; and Frith and dotterel (C, morinellus). (1969) states that 'on wet ground they shuffle 1 foot In New Zealand. foot-tremblingu in the black-fronted and stand on the other, and they thus flush prey animals.' dotterel (C. -

Partridges, Quails, Pheasants and Turkeys Phasianidae Vigors, 1825: Zoological Journal 2: 402 – Type Genus Phasianus Linnaeus, 1758

D .W . .5 / DY a 5D t w[ { wt Ç"" " !W5 í ÇI &'(' / b ù b a L w 5 ! ) " í "* " Ç t+ t " h " * { b ù" t* &)/&0 Order GALLIFORMES: Game Birds and Allies The order of galliform taxa in Checklist Committee (1990) appears to have been based on Peters (1934). Johnsgard (1986) synthesised available data, came up with similar groupings of taxa, and produced a dendrogram indicating that turkeys (Meleagridinae) were the most primitive (outside Cracidae and Megapodiidae), with grouse (Tetraoninae), guineafowl (Numidinae), New World quails (Odontophorinae) and pheasants and kin (Phasianinae) successively more derived. Genetic evidence (DNA-hybridisation data) provided by Sibley & Ahlquist (1990) suggested Odontophorinae were the most basal phasianoids and guineafowl the next most basal group. A basal position of the New World quails among phasianoids has been supported by other genetic data (Kimball et al. 1999, Armstrong et al. 2001). A recent analysis based on morphological characters (Dyke et al. 2003) found support for megapodes as the most basal group in the order, then Cracidae, then Phasianidoidea, and within the latter, Numididae the most basal group. In contrast to the above genetic-based analyses, Dyke et al. (2003) found the Odontophorinae to be the most derived group within the order. A recent analysis using both mitochondrial ND2 and cytochrome-b DNA sequences, however, reinforces the basal position of the Odontophorinae (Pereira & Baker 2006). Here we follow a consensus of the above works and place Odontophorinae basal in the phasianids. Worthy & Holdaway (2002) considered that Cheeseman’s (1891) second-hand record of megapodes from Raoul Island, Kermadec Group, before the 1870 volcanic eruption has veracity.