Visual Recognition of Females by Male Calopteryx Maculata (Odonata: Calopterygidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANDJUS, L. & Z.ADAMOV1C, 1986. IS&Zle I Ogrozene Vrste Odonata U Siroj Okolin

OdonatologicalAbstracts 1985 NIKOLOVA & I.J. JANEVA, 1987. Tendencii v izmeneniyata na hidrobiologichnoto s’soyanie na (12331) KUGLER, J., [Ed.], 1985. Plants and animals porechieto rusenski Lom. — Tendencies in the changes Lom of the land ofIsrael: an illustrated encyclopedia, Vol. ofthe hydrobiological state of the Rusenski river 3: Insects. Ministry Defence & Soc. Prol. Nat. Israel. valley. Hidmbiologiya, Sofia 31: 65-82. (Bulg,, with 446 col. incl. ISBN 965-05-0076-6. & Russ. — Zool., Acad. Sei., pp., pis (Hebrew, Engl. s’s). (Inst. Bulg. with Engl, title & taxonomic nomenclature). Blvd Tzar Osvoboditel 1, BG-1000 Sofia). The with 48-56. Some Lists 7 odon. — Lorn R. Bul- Odon. are dealt on pp. repre- spp.; Rusenski valley, sentative described, but checklist is spp. are no pro- garia. vided. 1988 1986 (12335) KOGNITZKI, S„ 1988, Die Libellenfauna des (12332) ANDJUS, L. & Z.ADAMOV1C, 1986. IS&zle Landeskreises Erlangen-Höchstadt: Biotope, i okolini — SchrReihe ogrozene vrste Odonata u Siroj Beograda. Gefährdung, Förderungsmassnahmen. [Extinct and vulnerable Odonata species in the broader bayer. Landesaml Umweltschutz 79: 75-82. - vicinity ofBelgrade]. Sadr. Ref. 16 Skup. Ent. Jugosl, (Betzensteiner Str. 8, D-90411 Nürnberg). 16 — Hist. 41 recorded 53 localities in the VriSac, p. [abstract only]. (Serb.). (Nat. spp. were (1986) at Mus., Njegoseva 51, YU-11000 Beograd, Serbia). district, Bavaria, Germany. The fauna and the status of 27 recorded in the discussed, and During 1949-1950, spp. were area. single spp. are management measures 3 decades later, 12 spp. were not any more sighted; are suggested. they became either locally extinct or extremely rare. A list is not provided. -

Predictive Modelling of Spatial Biodiversity Data to Support Ecological Network Mapping: a Case Study in the Fens

Predictive modelling of spatial biodiversity data to support ecological network mapping: a case study in the Fens Christopher J Panter, Paul M Dolman, Hannah L Mossman Final Report: July 2013 Supported and steered by the Fens for the Future partnership and the Environment Agency www.fensforthefuture.org.uk Published by: School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, NR4 7TJ, UK Suggested citation: Panter C.J., Dolman P.M., Mossman, H.L (2013) Predictive modelling of spatial biodiversity data to support ecological network mapping: a case study in the Fens. University of East Anglia, Norwich. ISBN: 978-0-9567812-3-9 © Copyright rests with the authors. Acknowledgements This project was supported and steered by the Fens for the Future partnership. Funding was provided by the Environment Agency (Dominic Coath). We thank all of the species recorders and natural historians, without whom this work would not be possible. Cover picture: Extract of a map showing the predicted distribution of biodiversity. Contents Executive summary .................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 6 Biological data ................................................................................................................... -

Odonata from Highlands in Niassa, with Two New Country Records

72 Odonata from highlands in Niassa, Mozambique, with two new country records Merlijn Jocque1,2*, Lore Geeraert1,3 & Samuel E.I. Jones1,4 1 Biodiversity Inventory for Conservation NPO (BINCO), Walmersumstraat 44, 3380 Glab- beek, Belgium; [email protected] 2 Aquatic and Terrestrial Ecology (ATECO), Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS), Vautierstraat 29, 1000 Brussels, Belgium 3 Plant Conservation and Population Biology, University of Leuven, Kasteelpark Arenberg 31-2435, BE-3001 Leuven, Belgium 4 Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham Surrey TW20 OEX, United Kingdom * Corresponding author Abstract. ‘Afromontane’ ecosystems in Eastern Africa are biologically highly valuable, but many remain poorly studied. We list dragonfly observations of a Biodiversity Express Survey to the highland areas in north-west Mozambique, exploring for the first time the Njesi Pla- teau (Serra Jecci/Lichinga plateau), Mt Chitagal and Mt Sanga, north of the provincial capital of Lichinga. A total of 13 species were collected. Allocnemis cf. abbotti and Gynacantha im maculifrons are new records for Mozambique. Further key words. Dragonfly, damselfly, Anisoptera, Zygoptera, biodiversity, survey Introduction The mountains of the East African Rift, stretching south from Ethiopia to Mozam- bique, are known to harbour a rich biological diversity owing to their unique habi- tats and long periods of isolation. Typically comprised of evergreen montane forests interspersed with high altitude grassland/moorland habitats, these montane archi- pelagos, often volcanic in origin, have been widely documented as supporting high levels of endemism across taxonomic groups and are of international conservation value (Myers et al. 2000). While certain mountain ranges within this region have been relatively well studied biologically e.g. -

Identification Guide to the Australian Odonata Australian the to Guide Identification

Identification Guide to theAustralian Odonata www.environment.nsw.gov.au Identification Guide to the Australian Odonata Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW Identification Guide to the Australian Odonata Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data Theischinger, G. (Gunther), 1940– Identification Guide to the Australian Odonata 1. Odonata – Australia. 2. Odonata – Australia – Identification. I. Endersby I. (Ian), 1941- . II. Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW © 2009 Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW Front cover: Petalura gigantea, male (photo R. Tuft) Prepared by: Gunther Theischinger, Waters and Catchments Science, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW and Ian Endersby, 56 Looker Road, Montmorency, Victoria 3094 Published by: Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street Sydney PO Box A290 Sydney South 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131555 (information & publication requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au The Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW is pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. ISBN 978 1 74232 475 3 DECCW 2009/730 December 2009 Printed using environmentally sustainable paper. Contents About this guide iv 1 Introduction 1 2 Systematics -

Ohio Damselfly Species Checklist

Ohio Damselfly Species Checklist Ohio has ~51 species of damselflies (Zygoptera). This is a statewide species checklist to encourage observations of damselflies for the Ohio Dragonfly Survey. Please submit photo observations to iNaturalist.org. More information can be found on our survey website at u.osu.edu/ohioodonatasurvey/ Broad Winged Damselflies (Calopterygidae) 1 Appalachian Jewelwing Calopteryx angustipennis 2 River Jewelwing Calopteryx aequabilis State Endangered 3 Ebony Jewelwing Calopteryx maculata 4 American Rubyspot Hetaerina americana 5 Smoky Rubyspot Hetaerina titia Pond Damselflies (Coenagrionidae) 6 Eastern Red Damsel Amphiagrion saucium 7 Blue-fronted Dancer Argia apicalis 8 Seepage Dancer Argia bipunctulata State Endangered 9 Powdered Dancer Argia moesta 10 Blue-ringed Dancer Argia sedula 11 Blue-tipped Dancer Argia tibialis 12 Dusky Dancer Argia translata 13 Violet Dancer Argia fumipennis violacea 14 Aurora Damsel Chromagrion conditum 15 Taiga Bluet Coenagrion resolutum 16 Turquoise Bluet Enallagma divagans 17 Hagen's Bluet Enallagma hageni 18 Boreal Bluet Enallagma boreale State Threatened 19 Northern Bluet Enallagma annexum State Threatened 20 Skimming Bluet Enallagma geminatum 21 Orange Bluet Enallagma signatum 22 Vesper Bluet Enallagma vesperum 23 Marsh Bluet Enallagma ebrium State Threatened 24 Stream Bluet Enallagma exsulans 25 Rainbow Bluet Enallagma antennatum 26 Tule Bluet Enallagma carunculatum 27 Atlantic Bluet Enallagma doubledayi 1 28 Familiar Bluet Enallagma civile 29 Double-striped Bluet Enallagma basidens -

Impact of Environmental Changes on the Behavioral Diversity of the Odonata (Insecta) in the Amazon Bethânia O

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Impact of environmental changes on the behavioral diversity of the Odonata (Insecta) in the Amazon Bethânia O. de Resende1,2*, Victor Rennan S. Ferreira1,2, Leandro S. Brasil1, Lenize B. Calvão2,7, Thiago P. Mendes1,6, Fernando G. de Carvalho1,2, Cristian C. Mendoza‑Penagos1, Rafael C. Bastos1,2, Joás S. Brito1,2, José Max B. Oliveira‑Junior2,3, Karina Dias‑Silva2, Ana Luiza‑Andrade1, Rhainer Guillermo4, Adolfo Cordero‑Rivera5 & Leandro Juen1,2 The odonates are insects that have a wide range of reproductive, ritualized territorial, and aggressive behaviors. Changes in behavior are the frst response of most odonate species to environmental alterations. In this context, the primary objective of the present study was to assess the efects of environmental alterations resulting from shifts in land use on diferent aspects of the behavioral diversity of adult odonates. Fieldwork was conducted at 92 low‑order streams in two diferent regions of the Brazilian Amazon. To address our main objective, we measured 29 abiotic variables at each stream, together with fve morphological and fve behavioral traits of the resident odonates. The results indicate a loss of behaviors at sites impacted by anthropogenic changes, as well as variation in some morphological/behavioral traits under specifc environmental conditions. We highlight the importance of considering behavioral traits in the development of conservation strategies, given that species with a unique behavioral repertoire may sufer specifc types of extinction pressure. Te enormous variety of behavior exhibited by most animals has inspired human thought, arts, and Science for centuries, from rupestrian paintings to the Greek philosophers. -

From the Ebony Jewelwing Damsel

Comp. Parasitol. 71(2), 2004, pp. 141–153 Calyxocephalus karyopera g. nov., sp. nov. (Eugregarinorida: Actinocephalidae: Actinocephalinae) from the Ebony Jewelwing Damselfly Calopteryx maculata (Zygoptera: Calopterygidae) in Southeast Nebraska, U.S.A.: Implications for Mechanical Prey–Vector Stabilization of Exogenous Gregarine Development RICHARD E. CLOPTON Department of Natural Science, Peru State College, Peru, Nebraska 68421, U.S.A. (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT: Calyxocephalus karyopera g. nov., sp. nov. (Apicomplexa: Eugregarinorida: Actinocephalidae: Actino- cephalinae) is described from the Ebony Jewelwing Damselfly Calopteryx maculata (Odonata: Zygoptera: Calopteryigidae) collected along Turkey Creek in Johnson County, Nebraska, U.S.A. Calyxocephalus gen. n. is distinguished by the form of the epimerite complex: a terminal thick disk or linearly crateriform sucker with a distal apopetalus calyx of petaloid lobes and a short intercalating diamerite (less than half of the total holdfast length). The epimerite complex is conspicuous until association and syzygy. Association occurs immediately before syzygy and is cephalolateral and biassociative. Gametocysts are spherical with a conspicuous hyaline coat. Lacking conspicuous sporoducts they dehisce by simple rupture. Oocysts are axially symmetric, hexagonal dipyramidic in shape with slight polar truncations, bearing 6 equatorial spines, 1 at each equatorial vertex and 6 terminal spines obliquely inserted at each pole, 1 at each vertex created by polar truncation. The ecology of the C. karyopera–C. maculata host–parasite system provides a mechanism for mechanical prey–vector stabilization of exogenous gregarine development and isolation. KEY WORDS: Odonata, Zygoptera, Calopteryx maculata, damselfly, Apicomplexa, Eugregarinida, Actinocephalidae, Actinocephalinae, Calyxocephalus karyopera, new genus, new species, parasite evolution, biodiversity, species isolation, vector, transmission. -

The Classification and Diversity of Dragonflies and Damselflies (Odonata)*

Zootaxa 3703 (1): 036–045 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Correspondence ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.9 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9F5D2E03-6ABE-4425-9713-99888C0C8690 The classification and diversity of dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata)* KLAAS-DOUWE B. DIJKSTRA1, GÜNTER BECHLY2, SETH M. BYBEE3, RORY A. DOW1, HENRI J. DUMONT4, GÜNTHER FLECK5, ROSSER W. GARRISON6, MATTI HÄMÄLÄINEN1, VINCENT J. KALKMAN1, HARUKI KARUBE7, MICHAEL L. MAY8, ALBERT G. ORR9, DENNIS R. PAULSON10, ANDREW C. REHN11, GÜNTHER THEISCHINGER12, JOHN W.H. TRUEMAN13, JAN VAN TOL1, NATALIA VON ELLENRIEDER6 & JESSICA WARE14 1Naturalis Biodiversity Centre, PO Box 9517, NL-2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 2Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Rosenstein 1, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Biology, Brigham Young University, 401 WIDB, Provo, UT. 84602 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 4Department of Biology, Ghent University, Ledeganckstraat 35, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected] 5France. E-mail: [email protected] 6Plant Pest Diagnostics Branch, California Department of Food & Agriculture, 3294 Meadowview Road, Sacramento, CA 95832- 1448, USA. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 7Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Natural History, 499 Iryuda, Odawara, Kanagawa, 250-0031 Japan. E-mail: [email protected] 8Department of Entomology, Rutgers University, Blake Hall, 93 Lipman Drive, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901, USA. -

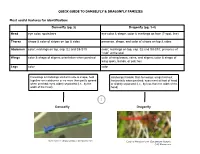

Dragonfly (Pg. 3-4) Head Eye Color

QUICK GUIDE TO DAMSELFLY & DRAGONFLY FAMILIES Most useful features for identification: Damselfly (pg. 2) Dragonfly (pg. 3-4) Head eye color; spots/bars eye color & shape; color & markings on face (T-spot, line) Thorax shape & color of stripes on top & sides presence, shape, and color of stripes on top & sides Abdomen color; markings on top, esp. S2 and S8-S10 color; markings on top, esp. S2 and S8-S10; presence of “club” at the end Wings color & shape of stigma; orientation when perched color of wing bases, veins, and stigma; color & shape of wing spots, bands, or patches Legs color color Forewings & hindwings similar in size & shape, held Hindwings broader than forewings; wings held out together over abdomen or no more than partly spread horizontally when perched; eyes meet at front of head when perched; eyes widely separated (i.e., by the or slightly separated (i.e., by less than the width of the width of the head) head) 1 Damselfly Dragonfly Vivid Dancer (Argia vivida); CAS Mazzacano Cardinal Meadowhawk (Sympetrum illotum); CAS Mazzacano DAMSELFLIES Wings narrow, stalked at base 2 Wings broad, colored, not stalked at base 3 Wings held askew Wings held together Broad-winged Damselfly when perched when perched (Calopterygidae); streams Spreadwing Pond Damsels (Coenagrionidae); (Lestidae); ponds ponds, streams Dancer (Argia); Wings held above abdomen; vivid colors streams 4 Wings held along Bluet (Enallagma); River Jewelwing (Calopteryx aequabilis); abdomen; mostly blue ponds CAS Mazzacano Dark abdomen with blue Forktail (Ischnura); tip; -

Developing an Odonate-Based Index for Monitoring Freshwater Ecosystems in Rwanda: Towards Linking Policy to Practice Through Integrated and Adaptive Management

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2020 Developing an Odonate-Based Index for Monitoring Freshwater Ecosystems in Rwanda: Towards Linking Policy to Practice through Integrated and Adaptive Management Erasme Uyizeye Follow this and additional works at: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Entomology Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Department of Environmental Studies DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PAGE The undersigned have examined the dissertation entitled: Developing an Odonate-Based Index for Monitoring Freshwater Ecosystems in Rwanda: Towards Linking Policy to Practice through Integrated and Adaptive Management, presented by Erasme Uyizeye, candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that it is accepted*. Committee Chair: Beth A. Kaplin, Ph.D. Antioch University New England, USA Committee member: Lisabeth Willey, Ph.D. Antioch University New England, USA Committee member: Viola Clausnitzer, Ph.D. Senckenberg Museum of Natural History Görlitz, Germany. Defense Date: April 17th, 2020. Date Approved by all Committee Members: April 30th, 2020. Date Deposited: April 30th, 2020. *Signatures are on file with the Registrar’s Office at Antioch University New England. Developing an Odonate-Based Index for Monitoring Freshwater Ecosystems in Rwanda: Towards Linking Policy to Practice through Integrated and Adaptive Management By Erasme Uyizeye A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Environmental Studies at Antioch University New England Keene, New Hampshire 2020 ii © 2020 by Erasme Uyizeye All rights reserve iii Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my daughter who was born in the midst of this doctoral journey, my wife who has stayed by my side, my father for his words of encouragement (1956-1993) & my mother for her unwavering support and love. -

Calopteryx Splendens, C. Virgo) During Social Interaction: a Signal Or a Symptom?

Russian Entomol. J. 25(1): 103–120 © RUSSIAN ENTOMOLOGICAL JOURNAL, 2016 Behaviour of two demoiselle species (Calopteryx splendens, C. virgo) during social interaction: a signal or a symptom? Ïîâåäåíèå äâóõ âèäîâ ðàâíîêðûëûõ ñòðåêîç êðàñîòêè áëåñòÿùåé Calopteryx splendens Harris, 1780 è êðàñîòêè-äåâóøêè C. virgo Linnaeus, 1758 (Odonata, Calopterygidae) E.N. Panov1*, A.S. Opaev1, E.Yu. Pavlova1, V.A. Nepomnyashchikh2 Å.Í. Ïàíîâ1*, À.Ñ. Îïàåâ1, Å.Þ. Ïàâëîâà1, Â.À. Íåïîìíÿùèõ2 1 A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninsky prosp., 33, Moscow, 119071 Russia. 1 Институт проблем экологии и эволюции им. А.Н. Северцова РАН, Ленинский просп., 33, Москва 119071 Россия. 2 Institute of Biology of Inland Waters, Russian Academy of Sciences, Borok, 152742 Russia. 2 Институт биологии внутренних вод РАН, п. Борок, Ярославская область, 152742 Россия. * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] KEY WORDS: damselfly, agonistic behaviour, evolution of courtship behaviour, sexual selection. КЛЮЧЕВЫЕ СЛОВА: стрекоза, агонистическое поведение, эволюция поведения ухаживания, половой отбор. ABSTRACT. Based on the analysis of video record- ного характера. Подвержены серьезной критике ings, obtained during five field seasons, we suggest a трактовки функциональных объяснений поведения pattern of analytical description of damselfly (Zygoptera: стрекоз, господствующие в современной литерату- Calopterygidae) behaviour in a broad spectrum of so- ре по этим насекомым и основанные на откровен- cial contexts. The arrays of motor coordinations and ном антропоморфизме. Этому подходу противопо- their place in social interactions are studied compara- ставлен совершенно иной, призывающий к возвра- tively and in the temporal dynamic. The first description ту к оставленным в последние десятилетия методам of the full set of behaviours of Banded Demoiselles и принципам, разработанным ранее в рамках поле- Calopteryx splendens is given; the respective data for вой и аналитической этологии. -

An Assessment of Marking Techniques for Odonates in the Family Calopterygidae

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title An assessment of marking techniques for odonates in the family Calopterygidae Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1m5071bs Journal Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 141(3) ISSN 00138703 Authors Anderson, Christopher N Cordoba-Aguilar, Alex Drury, Jonathan P et al. Publication Date 2011-12-01 DOI 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2011.01185.x Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California DOI: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2011.01185.x TECHNICAL NOTE An assessment of marking techniques for odonates in the family Calopterygidae Christopher N. Anderson1*, Alex Cordoba-Aguilar1,JonathanP.Drury2 & Gregory F.Grether2 1Departamento de Ecologı´a Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecologı´a, Universidad Nacional Auto´noma de Me´xico, Circuito Exterior s ⁄ n, Apdo. Postal 70-275, Me´xico, D.F. 04510, Mexico, and 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California at Los Angeles, 621 Charles E. Young Drive South, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1606, USA Accepted: 13 September 2011 Key words: Odonata, paint and ink marking, mark-capture, Calopteryx haemorrhoidalis, Hetaerina titia,damselfly tion. These manipulations significantly influenced mating Introduction success (Grether, 1996a,b), foraging success (Grether & Marking effects (e.g., changes to behavior, survival, or Grey, 1996), survival (Grether, 1997), and territorial reproduction after manipulation) are likely to be com- aggression against conspecifics and, in some instances, mon, as researchers have found effects in a variety of taxa, against heterospecifics (Anderson & Grether, 2010, 2011). including mammals (Moorhouse & Macdonald, 2005), Therefore, using wing marking to identify individuals may birds (Burley et al., 1982; Hunt et al., 1997; Gauthier-Clerc be problematic for investigations of reproductive, territo- et al., 2004), and amphibians (McCarthy & Parris, 2004).