Proper Names in Translations for Children: Alice in Wonderland As a Case in Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice in Wonderland: Chapter Seven: a Mad Tea Party

ALICE IN WONDERLAND: CHAPTER SEVEN: A MAD TEA PARTY CHAPTER VII A Mad Tea-Party There was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion, resting their elbows on it, and talking over its head. `Very uncomfortable for the Dormouse,' thought Alice; `only, as it's asleep, I suppose it doesn't mind.' The table was a large one, but the three were all crowded together at one corner of it: `No room! No room!' they cried out when they saw Alice coming. `There's plenty of room!' said Alice indignantly, and she sat down in a large arm-chair at one end of the table. Mad Tea Party `Have some wine,' the March Hare said in an encouraging tone. Alice looked all round the table, but there was nothing on it but tea. `I don't see any wine,' she remarked. `There isn't any,' said the March Hare. `Then it wasn't very civil of you to offer it,' said Alice angrily. `It wasn't very civil of you to sit down without being invited,' said the March Hare. `I didn't know it was your table,' said Alice; `it's laid for a great many more than three.' 1 ALICE IN WONDERLAND: CHAPTER SEVEN: A MAD TEA PARTY `Your hair wants cutting,' said the Hatter. He had been looking at Alice for some time with great curiosity, and this was his first speech. -

Lewis Carroll: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND by Lewis Carroll with fourty-two illustrations by John Tenniel This book is in public domain. No rigths reserved. Free for copy and distribution. This PDF book is designed and published by PDFREEBOOKS.ORG Contents Poem. All in the golden afternoon ...................................... 3 I Down the Rabbit-Hole .......................................... 4 II The Pool of Tears ............................................... 9 III A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale .................................. 14 IV The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill ................................. 19 V Advice from a Caterpillar ........................................ 25 VI Pig and Pepper ................................................. 32 VII A Mad Tea-Party ............................................... 39 VIII The Queen’s Croquet-Ground .................................... 46 IX The Mock Turtle’s Story ......................................... 53 X The Lobster Quadrille ........................................... 59 XI Who Stole the Tarts? ............................................ 65 XII Alice’s Evidence ................................................ 70 1 Poem All in the golden afternoon Of wonders wild and new, Full leisurely we glide; In friendly chat with bird or beast – For both our oars, with little skill, And half believe it true. By little arms are plied, And ever, as the story drained While little hands make vain pretence The wells of fancy dry, Our wanderings to guide. And faintly strove that weary one Ah, cruel Three! In such an hour, To put the subject by, Beneath such dreamy weather, “The rest next time –” “It is next time!” To beg a tale of breath too weak The happy voices cry. To stir the tiniest feather! Thus grew the tale of Wonderland: Yet what can one poor voice avail Thus slowly, one by one, Against three tongues together? Its quaint events were hammered out – Imperious Prima flashes forth And now the tale is done, Her edict ‘to begin it’ – And home we steer, a merry crew, In gentler tone Secunda hopes Beneath the setting sun. -

SEMANTIC DEMARCATION of the CONCEPTS of ENDONYM and EXONYM PRISPEVEK K POMENSKI RAZMEJITVI TERMINOV ENDONIM in EKSONIM Drago Kladnik

Acta geographica Slovenica, 49-2, 2009, 393–428 SEMANTIC DEMARCATION OF THE CONCEPTS OF ENDONYM AND EXONYM PRISPEVEK K POMENSKI RAZMEJITVI TERMINOV ENDONIM IN EKSONIM Drago Kladnik BLA@ KOMAC Bovec – Flitsch – Plezzo je mesto na zahodu Slovenije. Bovec – Flitsch – Plezzo is a town in western Slovenia. Drago Kladnik, Semantic Demarcation of the Concepts of Endonym and Exonym Semantic Demarcation of the Concepts of Endonym and Exonym DOI: 10.3986/AGS49206 UDC: 81'373.21 COBISS: 1.01 ABSTRACT: This article discusses the delicate relationships when demarcating the concepts of endonym and exonym. In addition to problems connected with the study of transnational names (i.e., names of geographical features extending across the territory of several countries), there are also problems in eth- nically mixed areas. These are examined in greater detail in the case of place names in Slovenia and neighboring countries. On the one hand, this raises the question of the nature of endonyms on the territory of Slovenia in the languages of officially recognized minorities and their respective linguistic communities, and their relationship to exonyms in the languages of neighboring countries. On the other hand, it also raises the issue of Slovenian exonyms for place names in neighboring countries and their relationship to the nature of Slovenian endonyms on their territories. At a certain point, these dimensions intertwine, and it is there that the demarcation between the concepts of endonym and exonym is most difficult and problematic. KEY WORDS: geography, geographical names, endonym, exonym, exonimization, geography, linguistics, terminology, ethnically mixed areas, Slovenia The article was submitted for publication on May 4, 2009. -

“Borders/ Debordering”

“BORDERS/ DEBORDERING” number 83/84 • volume 21, 2016 EDITED BY HELENA MOTOH MAJA BJELICA POLIGRAFI Editor-in-Chief: Helena Motoh (Univ. of Primorska) Editorial Board: Lenart Škof (Univ. of Primorska), Igor Škamperle (Univ. of Ljubljana), Mojca Terčelj (Univ. of Primorska), Miha Pintarič (Univ. of Ljubljana), Rok Svetlič (Univ. of Primorska), Anja Zalta (Univ. of Ljubljana) Editorial Office: University of Primorska, Science and Research Centre, Institute for Philosophical Studies, Garibaldijeva 1, SI-6000 Koper, Slovenia Phone: +386 5 6637 700, Fax: + 386 5 6637 710, E-mail: [email protected] http://www.poligrafi.si number 83/84, volume 21 (2016) “BORDERS/DEBORDERING” TOWARDS A NEW WORLD CULTURE OF HOSPITALITY Edited by Helena Motoh and Maja Bjelica International Editorial Board: Th. Luckmann (Universität Konstanz), D. Kleinberg-Levin (Northwestern University), R. A. Mall (Universität München), M. Ježić (Filozofski fakultet, Zagreb), D. Louw (University of the Free State, Bloemfontain), M. Volf (Yale University), K. Wiredu (University of South Florida), D. Thomas (University of Birmingham), M. Kerševan (Filozofska fakulteta, Ljubljana), F. Leoncini (Università degli Studi di Venezia), P. Zovatto (Università di Trieste), T. Garfitt (Oxford University), M. Zink (Collège de France), L. Olivé (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), A. Louth (Durham University), P. Imbert (University of Ottawa), Ö. Turan (Middle-East Technical University, Ankara), E. Krotz (Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán / Universidad Autónoma de Metropolitana-Iztapalapa), -

Das Rumnische Ortsnamengesetz Und Seine

Review of Historical Geography and Toponomastics, vol. I, no. 2, 2006, pp. 125-132 UNITED NATIONS GROUP OF EXPERTS ON GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 6th MEETING OF THE WORKING GROUP ON EXONYMS PRAGUE (PRAHA), th th CZECH REPUBLIC, 17 – 18 MAY 2007 ∗ Peter JORDAN ∗ Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Postgasse 7/4/2, 1010 Wien. Summary report. United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names 6th Meeting of the Working Group on Exonyms Prague [Praha], Czech Republic, 17th – 18th May 2007. This two-day meeting was jointly arranged with the EuroGeoNames Project and part of a meeting on geographical names in conjunction with a meeting of the UNGEGN East, Central and Southeast-East Europe Division. It was hosted by the Czech Land Survey Office and took place in the premises of this Office, Praha, Pod sídlištěm 9/1800. Participants and the papers presented are listed in the Annex to this Report. The meeting was opened and the delegates welcomed by Ms Helen Kerfoot, the UNGEGN Chair, Mr. Peter Jordan, the Working Group’s Co-convenor and Mr. Jörn Sievers as the representative of the EuroGeoNames Project. In her opening address Ms. Kerfoot emphasized that UNGEGN views on exonyms had somewhat changed in recent years. All the three opening addresses referred to Mr. Pavel Boháč, the meeting’s principal organiser, thanking him for his great efforts. Mr. Jordan then outlined the programme of this meeting and its main task of clarifying the use of exonyms in an empirical (in which situations are exonyms actually used?) and in a normative (in which situations should exonyms be used or not be used?) way. -

Free Ebooks ==> Www

Free ebooks ==> www.Ebook777.com US/CAN $19.95 BusINESS & EcONOMIcs A Do-It-Yourself Guide to Financial, Commercial, Political, Social and Cultural Collapse …one of the best writers on the scene today, working at the top of his game. There is more to enjoy in this book with every page you turn, and in very uncertain times, Orlov’s advice is, at its core, kind-spirited and extraordinarily helpful. Albert Bates, author, The Biochar Solution When thinking about political paralysis, looming resource shortages and a rapidly changing climate, many of us can do no better than imagine a future that is just less of the same. But it is during such periods of profound disruption that sweeping cultural change becomes inevitable. In The Five Stages of Collapse, Dmitry Orlov posits a taxonomy of collapse, suggesting that if the first three stages (financial, commercial and political) are met with the appropriate personal and social transformations, then the worst consequences of social and cultural collapse can be avoided. Drawing on a detailed examination of both pre- and post-collapse societies, The Five Stages of Collapse provides a unique perspective on the typical characteristics of highly resilient communities. Both successful and unsuccessful adaptations are explored in the areas of finance, commerce, self-governance, social organization and culture. Case studies provide a wealth of specifics for each stage of collapse, focusing on the Icelanders, the Russian Mafia, the Pashtuns of Central Asia, the Roma of nowhere in particular and the Ik of East Africa. The Five Stages of Collapse provides a wealth of practical information and a long list of to-do items for those who wish to survive each stage with their health, sanity, friendships, family relationships and sense of humor intact. -

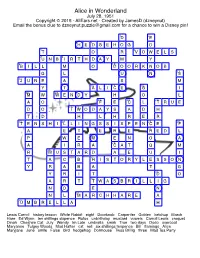

Alice in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland July 28, 1951 Copyright © 2015 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 D E 3 4 H E D G E H O G D 5 6 T O R V O W E L S 7 8 U N B I R T H D A Y M Y 9 10 B I L L M O D O O R K N O B 11 G L U N S 12 J U N E A S M 13 14 15 Y T A L I C E G I 16 17 M W W E N D Y H O L 18 19 20 A O F E C L T R U E 21 22 D O T W O D A Y S A D H T D H L H R E R 23 24 25 26 T E N S H I L L I N G S S I X P E N C E F 27 A E T E R E R E D L 28 P W E M E N O A 29 A I R A C A T Q M 30 R M U S T A R D A E U I 31 T A C B H I S T O R Y L E S S O N Y R A B A T G 32 Y R I T D O 33 A R T T W A S B R I L L I G N O E N 34 N L M A R C H H A R E A 35 U M B R E L L A H Lewis Carroll history lesson White Rabbit eight Doorknob Carpenter Golden ketchup March Hare Ed Wynn ten shillings sixpence Rufus unbirthday mustard vowels Carroll Lewis croquet Dinah Cheshire Cat July Wendy Im Late umbrella smirk True two days Dodo overcoat Maryanne Tulgey Woods Mad Hatter cat red six shillings tenpence Bill flamingo Alice Maryjane June smile False bird hedgehog Dormouse Twas Brillig three Mad Tea Party ★ Thurl Ravenscroft, a member of the singing group, the Mellomen, who sing #27 Across, appears to have lost his head while singing a familiar song in what popular theme park attraction? (2 words) [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 3. -

41/2017 I. Literature and Cultural Studies Grazziella Predoiu (Timiṣoara): the Lonely-Women Into Lo

Germanistische Beiträge: 41/2017 I. Literature and Cultural Studies Grazziella Predoiu (Timiṣoara): The lonely-women into lost path: Facts about the intercultural novel „The eartheaterin“ Abstract: The intercultural novel of Julya Rabinowich The Earth-eater is fed with complex motifs and intertextual allusions, shows the physical and psychological ruin of a migrant, forced by social conditions to sell her body to survive. Closely interwoven are memories of her childhood and her previous, bitter life.Rabinowich gives an insight into the hardened and thoroughly abysmal emotional world of her protagonist, who belongs to those who "get up and go on", but also into the capitalist value system, which judges man according to his productive power. In the end, the novel leaves the reality plane and echoes into the surreal to signal the complete descent of the figure into madness and death. In order to better illustrate the psychosis caused by uprooting and abandonment, Julya Rabinowich makes bonds in the Jewish literary traditions. Title and key-words: The lonely-women into lost path: Facts about the intercultural novel „The eartheaterin“; migration, foreignness, madness, death. Maria Sass (Sibiu): Erwin Wittstock’s novel Januar ’45 oder Die höhere Pflicht [January '45 or the higher duty]: The problematic of deportation from an intercultural perspective Abstract: Erwin Wittstock (1899-1962), the writer of German expression from Romania, has created a monumental body of works (short stories and novels), which stem from the German history and culture from Transylvania and the characters he created are projections of his own life. His novel Januar ’45 oder Die höhere Pflicht, viewed in the present article from an intercultural point of view, is dedicated to the problem of deportation, a topic that was taboo in the communist regime. -

White Rabbit (1967) Jefferson Airplane

MUSC-21600: The Art of Rock Music Prof. Freeze White Rabbit (1967) Jefferson Airplane LISTEN FOR • Surrealistic lyrics • Spanish inflections • Musical ambition contained in pop AABA form • Overarching dramatic arc (cf. Ravel’s Bolero?) CREATION Songwriters Grace Slick Album Surrealistic Pillow Label RCA Victor 47-9248 (single); LSP-3766 (stereo album) Musicians Electric guitars, bass, drums, vocals Producer Rick Jarrard Recording November 1966; stereo Charts Pop 8; Album 3 MUSIC Genre Psychedelic rock Form AABA Key F-sharp Phrygian mode Meter 4/4 LISTENING GUIDE Time Form Lyric Cue Listen For 0:00 Intro (12) • Bass guitar and snare drum suggest the Spanish bolero rhythm. • Phrygian mode common in flamenco music. • Winding guitar lines evoke Spanish music. • Heavy reverb in all instruments save drums. MUSC-21600 Listening Guide Freeze “White Rabbit” (Jefferson Airplane, 1967) Time Form Lyric Cue Listen For 0.28 A (12) “One pill makes you” • Vocals enter quietly and with echo, with only bass, guitar, and snare drum accompaniment. 0:55 A (12) “And if you go” • Just a little louder and more forceful. 1:23 B (12) “When men on” • Music gains intensity: louder dynamic, second guitar, drums with more traditional rock beat. 1:42 A (21) “Go ask Alice” • Vocal now much more forceful. • Accompaniment more insistent, especially rhythm guitar. • Drives to climax at end. LYRICS One pill makes you larger When the men on the chessboard And one pill makes you small Get up and tell you where to go And the ones that mother gives you And you’ve just had some -

Database of German Exonyms

GEGN.2/2021/46/CRP.46 15 March 2021 English United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names 2021 session New York, 3 – 7 May 2021 Item 13 of the provisional agenda * Exonyms Database of German Exonyms Submitted by Germany** Summary The permanent committee on geographical names (Ständiger Ausschuss für geographische Namen) has published the third issue of its list of German exonyms as a database. The list follows the relevant resolutions adopted by the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names and includes slightly more than 1,500 common German exonyms. It is therefore entirely possible to implement the recommendations of the toponymic experts as laid down in resolutions VIII/4, V/13, III/18, III/9, IV/20, II/28 (available at www.ngii.go.kr/portal/ungn/mainEn.do) which addresses the use of exonyms. The database software is open source. The database can be accessed on the permanent committee’s website as open data under a Creative Commons licence. The data sets can be queried by means of a user interface equipped with an extensive search function, or retrieved in the GeoPackage data format for geographic information system, which is non-proprietary, platform-independent and standards-based. * GEGN.2/2021/1 ** Prepared by Roman Stani-Fertl (Austria), submitted on behalf of the Permanent Committee on Geographical Names (Ständiger Ausschuss für geographische Namen – StAGN) GEGN.2/2021/46/CRP.46 Background In 2002, the Permanent Committee on Geographical Names representing the German speaking countries, has published the second edition of the list of “Selected German Language Exonyms”. -

KNIGHT LETTER D De E the Lewis Carroll Society of North America

d de e KNIGHT LETTER d de e The Lewis Carroll Society of North America Fall 2017 Volume II Issue 29 Number 99 d de e CONTENTS d de e The Rectory Umbrella Of Books and Things g g Delaware and Dodgson, Contemporary Review of or, Wonderlands: Egad! Ado! 1 Nabokov’s Anya Discovered 36 chris morgan victor fet Drawing the Looking-Glass Country 11 The Albanian Gheg Wonderland 36 dmitry yermolovich byron sewell Is snark Part of a Cyrillic Doublet? 16 Alice and the Graceful White Rabbit 37 victor fet & michael everson robert stek USC Libraries’ 13th Wonderland Award 18 Alice’s Adventures in Punch 38 linda cassady andrew ogus A “New” Lewis Carroll Puzzle 19 Alice’s Adventures under clare imholtz the Land of Enchantment 39 Two Laments: One for Logic cindy watter & One for the King 20 Alice D. 40 august a. imholtz, jr cindy watter Mad Hatters and March Hares 41 mischmasch rose owens g AW, ill. Charles Santore 41 andrew ogus Leaves from the Deanery Garden— Serendipity—Sic, Sic, Sic 21 Rare, Uncollected, & Unpublished Verse of Lewis Carroll 42 Ravings from the Writing Desk 25 edward wakeling stephanie lovett The Alice Books and the Contested All Must Have Prizes 26 Ground of the Natural World 42 matt crandall hayley rushing Arcane Illustrators: Goranka Vrus Murtić 29 Evergreen 43 mark burstein Nose Is a Nose Is a Nose 30 From Our Far-flung goetz kluge Correspondents g In Memoriam: Morton Cohen 32 Art & Illustration—Articles & Academia— edward guiliano Books—Events, Exhibits, & Places—Internet & Technology—Movies & Television—Music— Carrollian Notes Performing Arts—Things 44 g More on Morton 34 Alice in Puzzleland: The Jabberwocky Puzzle Project 34 chris morgan d e Drawing the Looking-Glass Country dmitry yermolovich d e llustrators do not often explain why they have Messerschmidt, famous for his “character heads,” drawn their pictures the way they did. -

Alice in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland Grade Level: Third Grade Presented by: Mary Beth Henze, Platte River Academy, Highlands Ranch, CO Paula Lowthian, Littleton Academy, Littleton, CO Length of Unit: 13 lessons I. ABSTRACT This literature unit was designed to assist students at various reading levels to both understand and enjoy Alice in Wonderland. It was our feeling that this novel is very challenging for the average 3rd grade reader. The story line can be difficult to follow and the author, Lewis Carroll, uses English terms and various “sayings and phrases” in his writing. First, we developed an Interest Center around the Alice theme, complete with pictures from the story and activities for the students to enjoy as a way to activate their prior knowledge and a way to incorporate fun thematic opportunities for the students. Second, we wrote a novel study complete with comprehension questions for each chapter. The questions ask the students for both explicit and implicit information, require the students to answer in complete sentences, touch on vocabulary and grammar, and invite them to make connections between themselves, other texts, or the outside world as they read Alice in Wonderland. The novel was read together as a whole class, and then students were sent off to individually work on their novel study questions. Together we reviewed the questions and answers as we enjoyed our progression through the novel. Finally, we took our lead from the students as they often ask us if they “can act out” a part of a story that they are reading by writing a script for the trial scene from Alice.