Love's Labor's Lost Dramatis Personae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT and ACCOUNTS the Courtyard Theatre Southern Lane Stratford-Upon-Avon Warwickshire CV37 6BH

www.rsc.org.uk +44 1789 294810 Fax: +44 1789 296655 Tel: 6BH CV37 Warwickshire Stratford-upon-Avon Southern Lane Theatre The Courtyard Company Shakespeare Royal ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2006 2007 2006 2007 131st REPORT CHAIRMAN’S REPORT 03 OF THE BOARD To be submitted to the Annual ARTISTIC DIRECTOR’S REPORT 04 General Meeting of the Governors convened for Friday 14 December EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S REPORT 07 2007. To the Governors of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon-Avon, notice is ACHIEVEMENTS 08 – 09 hereby given that the Annual General Meeting of the Governors will be held in The Courtyard VOICES 10 – 33 Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon on Friday 14 December 2007 FINANCIAL REVIEW OF THE YEAR 34 – 37 commencing at 2.00pm, to consider the report of the Board and the Statement of Financial SUMMARY ACCOUNTS 38 – 41 Activities and the Balance Sheet of the Corporation at 31 March 2007, to elect the Board for the SUPPORTING OUR WORK 42 – 43 ensuing year, and to transact such business as may be trans- AUDIENCE REACH 44 – 45 acted at the Annual General Meetings of the Royal Shakespeare Company. YEAR IN PERFORMANCE 46 – 51 By order of the Board ACTING COMPANIES 52 – 55 Vikki Heywood Secretary to the Governors THE COMPANY 56 – 57 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 58 ASSOCIATES/ADVISORS 59 CONSTITUTION 60 Right: Kneehigh Theatre perform Cymbeline photo: xxxxxxxxxxxxx Harriet Walter plays Cleopatra This has been a glorious year, which brought together the epic and the personal in ways we never anticipated when we set out to stage every one of Shakespeare’s plays, sonnets and long poems between April 2006 and April 2007. -

Nues Herald-Spectator

Your Local source since 1951. AWA1PORTS company ACHICAGO SUNf IMEScorn publication niles.suntimes.com Thursday, December 5,2013 I $1 I Nues Herald-Spectator KIDS SAY DON'T FEAR FIREFIGHTERS « GO GUIDE TO HOLIDAY EVENTS IN YOUR AREA MOMMY)) CHEESY HOMEMADE HOLIDAY It's home, for theholidays TREATS Morton Grove American Legion hosts sailors for Thanksgiving I PAGE 6 © 2013 Sun-Times Media All rights reserved Niles Herald-Spectator I your #1 source forhigh schoòl sports SCORES GAME STORIES I PLAYER PROFILES VIDEOHIGHLIGHTS 4 High School Cube News, Sun-Times Media's new high school sports website, launched this week. ft's the latest evoIuton in Chicago area prep sports coverage. High School Cube News will integrate all the -II S31IN highlights and live games from HighSchoolCube.com with the 060OOOo S N0.jo 095g comprehensive coverage formerly provided by Season Pass, .LSI -Lcg3Q J.>1WN.j 00OOO 5t0-3016to 069e Go to highschoolcubenews.com or click high school ctc$: PORTS' on your local newspaper site. CUBE! news ThURSDAY DECEMBER 5 2013 A PIONEER PRESS PUBLICATION NIL COLD WGUV BAN IÇ,c!R D RESIDENTIAL BROKERAGE AL THINKING: I4*muh equity do I have? COLD'WELL THINIV1G: How much happiness do you a CoId1JBankn1jìie.com Morton Grove $399,995 Morton Grove $340,000 Morton Grove $335,000 Morton Grove $319,200 Eileen Hoban 847-724-5800 O64oNaíraganselt.into Eileen Hoban 847-724-5800 ilsiia Forniva 847-696-0700 Patricia Furman 847-724-5800 Nues $294,000 Morton Grove $289,900 Morton Grove $239,900 Nues $239,000 Mies $750000 Jennhler Barcal 847-384-7503 Gigi Poteracid 847-277-2725 Paula McGrath 847-724-5800 Mary Lou Allen 847-866-8200 Sue Oleksy 773-230-4143 Morton Grove $239,000 Morton Grove $219,900 Morton Grove $209,500 Morton Grove $199,500 Anya Wilkomer 847-724-5800 Patricia Furrnan 847-724-5800 t40lLincoln-507.info Rita Masini 847-724-5800 S4OlLincnin-305.info Rda Masuni 047-724-5800 Nues $199,000 Nues $108,000 Morton Grove $449,500 Lily Hosseini 847-724-5800 Seta Ajram 773-467-5300 Robert Phillips 847-696-0700 Ask us about a home warranty. -

Gays Going Green

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 April 22, 2009 • vol 24 no 30 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Gays Going Green BY ANDREW DAVIS Mary With April being Earth Month and, more specifi- Morten cally, April 22 being Earth Day, Windy City Times is profiling two members of the LGBT community History Profile who are doing their part to keep Chicagoland page 6 green: Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD) of Greater Chicago Commissioner Debra Shore and Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum bi- ologist Doug Taron. Lesson The Shore thing Shore has been interested in the environment for decades. “From a young age I enjoyed being in nature,” Shore said. “My best friend’s family was very ac- tive in the outdoors. We went on camping trips Scott Hall: and, spurred by my friends, I participated in an Outward Bound [wilderness expedition] program New gay when I was in college—hiking and camping.” pol in IL That fascination with the environment has page 5 propelled her to volunteer to assist in restoring the forest preserves along the North Branch of the Chicago River in Cook County for the past 15 years. Shore also is a founding editor of Chicago Wilderness Magazine, and she served on then- President John Stroger’s Community Advisory Council on Land Management from 1997 to 2007 and is a founding board member of Friends of the Forest Preserves. page 5 Hannah Shore decided to run for a MWRD commission- er’s post—and won in 2006, becoming the first Former President Bill Clinton (above) delivered the keynote address at the grand opening Free lesbian to hold a county position. -

The Fellows Gazette Volume 46 Spring 2008

The Fellows Gazette Volume 46 Spring 2008 Join Us in Washington! The Roger Stevens Speaker Gerald Freedman Gerald Freedman is an Obie Award-winner and the first American director invited to direct at the Globe Theatre, London, England. He is regarded nationally for productions of classic drama, musicals, operas, new plays and television. Springtime in Washington DC! Gala Reception and Dinner Saturday Evening, April 19th Capital Hilton Hotel, 16th & K Streets, NW 7:00 pm—RECEPTION TO MEET NEW FELLOWS Open Bar & Delicious Hors d’oeuvres Hosted by Washington’s National Theatre and its President and Executive Director, Gerald Freedman Fellow Donn B. Murphy Gerald served as leading director of Joseph Papp's 8:00 pm—THE FELLOWS ANNUAL DINNER New York Shakespeare Festival (1960-71), the last four years as artistic director. He was co-artistic Saluting the New Fellows of 2008 director of John Houseman's The Acting Company An Elegant Seated Dinner, Cash Bar Available (1974-77) artistic director of the American Shakespeare Theatre (1978-79), and artistic director of Great Lakes Theater Festival (1985-1997). He has staged 26 of Shakespeare's plays, along with dozens of other world classics. He has directed celebrated actors such as Olympia Dukakis, James Earl Jones, Stacy Keach, Julie Harris, Charles Durning, Sam Waterston, Patti Lupone, Mandy Patinkin, Jean Stapleton, William Hurt, Carroll O'Connor and Kevin Kline. He made theatre history with his off-Broadway premiere of the landmark rock musical Hair, which opened the Public Theatre in 1967. -

Henryviii Program FINAL Lores.Pdf

b1737_HENR_Program.indd 1 4/23/13 5:22 PM —The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act I, Scene iii b1737_HENR_Program.indd 2 4/23/13 5:22 PM HENRY VIII Contents Chicago Shakespeare Theater 800 E. Grand on Navy Pier On the Boards 8 Chicago, Illinois 60611 A selection of notable CST 312.595.5600 events, plays and players www.chicagoshakes.com ©2013 Chicago Shakespeare Theater Point of View 12 All rights reserved. Artistic Director Barbara Gaines discusses her first staging of ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Barbara Gaines EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Criss Henderson Shakespeare’s late play PICTURED, COVER AND ABOVE: Gregory Wooddell and Christina Pumariega, Cast 19 photos by Bill Burlingham Playgoer’s Guide 20 Profiles 22 Scholar’s Notes 32 Scholar Stuart Sherman explores the elasticity of truth in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII www.chicagoshakes.com 3 b1737_HENR_Program.indd 3 4/23/13 5:22 PM unforgettable . Hyatt is proud to sponsor Chicago Shakespeare Theater. We’ve supported the theater since its inception and believe one unforgettable performance deserves another. Experience distinctive design, extraordinary service and award-winning cuisine at every Hyatt worldwide. For reservations, call or visit hyatt.com. HYATT name, design and related marks are trademarks of Hyatt Corporation. ©2012 Hyatt Corporation. All rights reserved. HCM29411.01.a_Shakespeare_Ad.indd 1 1/26/12 10:24 AM b1737_HENR_Program.indd 4 4/23/13 5:22 PM A MESSAGE FROM Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson Raymond F. McCaskey Artistic Director Executive Director Chair, Board of Directors DEAR FRIENDS Henry VIII was certainly a notorious king, but ironically Shakespeare’s work bearing his name is not often produced. -

Announcing the HARVEST

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE LCT3/LINCOLN CENTER THEATER WILL PRESENT THE WORLD PREMIERE OF “THE HARVEST” by SAMUEL D. HUNTER directed by DAVIS MCCALLUM CAST WILL FEATURE GIDEON GLICK, SCOTT JAECK, LEAH KARPEL, MADELEINE MARTIN, PETER MARK KENDALL, CHRISTOPHER SEARS, ZOË WINTERS Saturday, October 8 through Sunday, November 20 Opening Night is Monday, October 24 AT THE CLAIRE TOW THEATER LCT3/Lincoln Center Theater will open its 2016-2017 season with the world premiere of THE HARVEST, by Samuel D. Hunter, directed by Davis McCallum. THE HARVEST, whose cast will feature Gideon Glick, Scott Jaeck, Leah Karpel, Madeleine Martin, Peter Mark Kendall, Christopher Sears, and Zoë Winters, will begin performances Saturday, October 8th, and run for six weeks only through Sunday, November 20th at the Claire Tow Theater. Opening Night is Monday, October 24th. In the basement of a small evangelical church in Southeastern Idaho, a group of young missionaries is preparing to go to the Middle East. One of them—a young man (to be played by Peter Mark Kendall) who has recently lost his father—has bought a one-way ticket. But his plans are complicated when his estranged sister (to be played by Leah Karpel) returns home and makes it her mission to keep him there. THE HARVEST was commissioned by LCT3. SAMUEL D. HUNTER’s plays include The Whale (Lucille Lortel, Drama Desk, GLAAD Media awards; Drama League, Outer Critics Circle nominations), A Bright New Boise (Obie Award; Drama Desk nomination), The Few, A Great Wilderness, Rest, Pocatello, Lewiston, Clarkston, and most recently, The Healing. He is the recipient of a 2014 MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship, a 2012 Whiting Writers Award, the 2008 PoNY/Lark Fellowship, and an honorary doctorate from the University of Idaho. -

Program from the Production

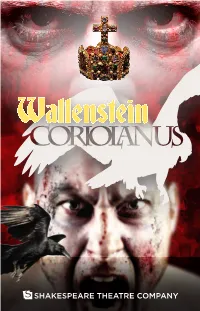

SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY Dear Friend, Table of Contents Welcome to STC’s Hero/ STC Board of Trustees Traitor Repertory, the first Coriolanus Title Page 5 installment in the Clarice Board of Trustees W. Mike House Emeritus Trustees Smith Repertory Series. Michael R. Klein, Chair Jerry J. Jasinowski R. Robert Linowes*, About the Playwright: Shakespeare 6 Robert E. Falb, Vice Chair Norman D. Jemal Founding Chairman William Shakespeare’s John Hill, Treasurer Jeffrey M. Kaplan James B. Adler Synopsis: Coriolanus 7 Coriolanus and Friedrich Pauline Schneider, Secretary Scott Kaufmann Heidi L. Berry* Michael Kahn, Artistic Director Abbe D. Lowell David A. Brody* Coriolanus Cast 9 Schiller’s Wallenstein Eleanor Merrill Melvin S. Cohen* share a stage because the title characters The Body Politic Trustees Melissa A. Moss Ralph P. Davidson share a dilemma: their power as charismatic Nicholas W. Allard Robert S. Osborne James F. Fitzpatrick by Drew Lichtenberg 10 Ashley M. Allen Stephen M. Ryan Dr. Sidney Harman* military leaders brings them into conflict with Stephen E. Allis George P. Stamas Lady Manning Wallenstein Title Page 11 the political world. In this North American Anita M. Antenucci Bill Walton Kathleen Matthews Jeffrey D. Bauman Lady Westmacott William F. McSweeny About the Playwright: Schiller 14 premiere of Schiller’s work, translated and Afsaneh Beschloss Rob Wilder V. Sue Molina freely adapted by former Poet Laureate Robert Landon Butler Suzanne S. Youngkin Walter Pincus Synopsis: Wallenstein 15 Pinsky, Wallenstein muses, “Once men have Dr. Paul Carter Eden Rafshoon Chelsea Clinton Ex-Officio Emily Malino Scheuer* Wallenstein Cast 17 climbed the heights of greatness…the world Dr. -

My Life in Art: a 21 Century Riff on Stanislavsky

st My Life in Art: A 21 Century Riff on Stanislavsky Gerald Freedman [Gerald Freedman’s address was presented at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington DC on April 20, 2008.] I’m honored and flattered to be asked to speak to this assembly of my distinguished peers. What can I say to you that you don’t know or haven’t experienced? Not much, I expect, except the story of my own journey. Yet I don’t like talking about myself. I find other people so much more interesting. I don’t want to preach about the state of the theatre or about its future. I don’t want to play either Il Dottore or Pantelone. All I really know is my journey. Then I think of what a remarkable journey I’ve had; the great mentors I’ve encountered, and the choices I’ve made, mostly by accident or coincidence, that have shaped my life. By the way, I like “mentor” rather than teacher, for myself as well as those I’ve worked with and worked under. In the dictionary, “teacher” has a dozen definitions. “Mentor” has two. One who shares and one who guides. But I like that. One who shares and one who guides. I want to think of mentoring as a collaboration, a master and journeyman relationship rather than a superior and a subordinate. Which one of us doesn’t feel that with each production we are again at zero—starting another learning project—and that’s the condition we share with our younger journeyman or apprentices. -

Splitting HAIR: Reviving the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical in the 1970S

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Faculty Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2018 Splitting HAIR: Reviving the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical in the 1970s Bryan M. Vandevender Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/fac_journ Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Other Music Commons, Theatre History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Vandevender, Bryan M.. "Splitting HAIR: Reviving the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical in the 1970s." New England Theatre Journal (2018) : 31-53. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Splitting Hair: Reviving the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical in the 1970s Bryan M. Vandevender When Hair premiered on Broadway in 1968, the musical garnered atten- tion for its reflection the current cultural moment. Critics acknowledged this congruence of form, content, and zeitgeist as the production’s great- est asset. This alignment with the Vietnam era proved a liability nine years later when Hair received its first Broadway revival, particularly when the musical’s authors replaced many of the libretto’s cultural refer- ences with allusions to the 1970s, further illuminating the musical’s inherently time-bound qualities. Critics and scholars frequently cite the 1968 Broadway premiere of Hair, the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical penned by James Rado, Gerome Ragni, and Galt MacDermot, as a turning point in the American musical’s maturation and development as it helped bring the form’s much mytholo- gized Golden Age to an end and opened the door to a new era of rock and concept musicals. -

Production List

PRODUCTION HISTORY Production Director 1935 California Pacific International Exposition Julius Caesar Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare The Taming of the Shrew Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare Hamlet Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare Much Ado About Nothing Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare The Comedy of Errors Theodore Viehman by William Shakespeare The Winter's Tale Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare As You Like It B. Iden Payne by William Shakespeare Macbeth Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare A Midsummer Night's Dream Theodore Viehman by William Shakespeare All's Well That Ends Well Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare Twelfth Night Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare Dr. Faustus Thomas Wood Stevens by Christopher Marlowe The Merry Wives of Windsor Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare 1936 Fortune Players The Tempest Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare King Henry VIII Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare The Two Gentlemen of Verona Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare PRODUCTION HISTORY Production Director Romeo and Juliet Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare Life and Death of Falstaff (adaptation) Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare The Comedy of Errors Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare The Tempest Thomas Wood Stevens by William Shakespeare 1937–1938 (Winter) The Distaff Side Luther M Kennett, Jr. by John Van Druten Small Miracle Luther M Kennett, Jr. by Norman Krasna Her Master's Voice Luther M Kennett, Jr. by Claire Cummer Dear Brutus Luther M. Kennett, Jr. by Sir James Barrie Once in a Lifetime Luther M Kennett, Jr. by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart Holiday Luther M Kennett, Jr. -

THE PUBLIC THEATER CONTINUES 57 YEARS of FREE SHAKESPEARE in the PARK at the DELACORTE THEATER MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING Directed by Kenny Leon May 21-June 23

THE PUBLIC THEATER CONTINUES 57 YEARS OF FREE SHAKESPEARE IN THE PARK AT THE DELACORTE THEATER MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING Directed by Kenny Leon May 21-June 23 CORIOLANUS Directed by Daniel Sullivan July 16-August 11 Public Works’ Musical Adaptation of HERCULES Music by Alan Menken Lyrics by David Zippel Book by Kristoffer Diaz Choreography by Chase Brock Directed by Lear deBessonet August 31-September 8 THE JEROME L. GREENE FOUNDATION & BANK OF AMERICA RETURN AS SEASON SPONSORS OF FREE SHAKESPEARE IN THE PARK February 6, 2019 − The Public Theater (Artistic Director, Oskar Eustis; Executive Director, Patrick Willingham) announced the line-up today for the 2019 Free Shakespeare in the Park season, continuing a 57-year tradition of free theater in Central Park. Since 1962, over five million people have enjoyed more than 150 free productions of Shakespeare and other classical works and musicals at the Delacorte Theater. Conceived by founder Joseph Papp as a way to make great theater accessible to all, The Public’s Free Shakespeare in the Park continues to be the bedrock of the Company’s mission to increase access and engage the community. This summer, Free Shakespeare in the Park will feature the romantic comedy MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING (May 21-June 23), directed by Tony Award winner Kenny Leon; and for the first time in 40 years, the war-torn tragedy CORIOLANUS, directed by Tony Award winner Daniel Sullivan (July 16- August 11). The Delacorte summer season will conclude with the seventh year of the acclaimed Public Works initiative with free performances of the Public Works’ musical adaptation of HERCULES (August 31-September 8), with music by Alan Menken, lyrics by David Zippel, book by Kristoffer Diaz, and directed by Lear deBessonet. -

THE EARLY HISTORY of the NEW YORK SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL Adam Sheaffer, Doctor

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: BUILDING PUBLIC(S): THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE NEW YORK SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL Adam Sheaffer, Doctor of Philosophy, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Franklin J. Hildy, School of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies This dissertation explores the New York Shakespeare Festival/Public Theater’s earliest history, with a special focus in the company’s evolving use of the rhetoric and concept of “public.” As founder Joseph Papp noted early in the theater’s history, they struggled to function as a “private organization engaged in public work.” To mitigate the challenges of this struggle, the company pursued potential audiences and publics for their theatrical and cultural offerings in a variety of spaces on the cityscape, from Central Park to neighborhood parks and common spaces to a 19th century historic landmark. In documenting and exploring the festival’s development and perambulations, this dissertation suggests that the festival’s position as both a private and public-minded organization presented as many opportunities as it did challenges. In this way, company rhetoric surrounding “public-ness” emerged as a powerful strategy for the company’s survival and growth, embodied most apparently by their current moniker as The Public Theater. BUILDING PUBLIC(S): THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE NEW YORK SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL by Adam Sheaffer Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Advisory Committee: Professor Franklin J. Hildy, Chair Professor Laurie Frederik Professor Faedra Chatard Carpenter Professor Kent Cartwright Professor Christina Hanhardt Professor Denise Albanese © Copyright by Adam Sheaffer 2018 Dedication For all those, living and not, that climb the hill to see the play ii Acknowledgements I must first and foremost thank my advisor Dr.