SIP RNA Extraction, Density Fractionation, and Qrt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Control Engineering Perspective on Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling

Control Engineering Perspective on Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling by Andrew Louis Damiani A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 12, 2015 Key words: Scheffersomyces stipitis, Flux Balance Analysis, Genome-scale metabolic models, System Identification Framework, Model Validation, Phenotype Phase Plane Analysis Copyright 2015 by Andrew Damiani Approved by Jin Wang, Chair, Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering Q. Peter He, Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering, Tuskegee University Thomas W. Jeffries, Professor of Bacteriology, Emeritus; University of Wisconsin-Madison Allan E. David, Assistant Professor of Chemical Engineering Yoon Y. Lee, Professor of Chemical Engineering Abstract Fossil fuels impart major problems on the global economy and have detrimental effects to the environment, which has caused a world-wide initiative of producing renewable fuels. Lignocellulosic bioethanol for renewable energy has recently gained attention, because it can overcome the limitations that first generation biofuels impose. Nonetheless, in order to have this process commercialized, the biological conversion of pentose sugars, mainly xylose, needs to be improved. Scheffersomyces stipitis has a physiology that makes it a valuable candidate for lignocellulosic bioethanol production, and lately has provided genes for designing recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In this study, a system biology approach was taken to understand the relationship of the genotype to phenotype, whereby genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) are used in conjunction with constraint-based modeling. The major restriction of GSMMs is having an accurate methodology for validation and evaluation. This is due to the size and complexity of the models. -

Human Catechol O-Methyltransferase Genetic Variation

Molecular Psychiatry (2004) 9, 151–160 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1359-4184/04 $25.00 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Human catechol O-methyltransferase genetic variation: gene resequencing and functional characterization of variant allozymes AJ Shield1, BA Thomae1, BW Eckloff2, ED Wieben2 and RM Weinshilboum1 1Department of Molecular Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Mayo Medical School, Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN, USA; 2Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Mayo Medical School, Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN, USA Catechol O-methyltransferase (COMT) plays an important role in the metabolism of catecholamines, catecholestrogens and catechol drugs. A common COMT G472A genetic polymorphism (Val108/158Met) that was identified previously is associated with decreased levels of enzyme activity and has been implicated as a possible risk factor for neuropsychiatric disease. We set out to ‘resequence’ the human COMT gene using DNA samples from 60 African-American and 60 Caucasian-American subjects. A total of 23 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), including a novel nonsynonymous cSNP present only in DNA from African-American subjects, and one insertion/deletion were observed. The wild type (WT) and two variant allozymes, Thr52 and Met108, were transiently expressed in COS-1 and HEK293 cells. There was no significant change in level of COMT activity for the Thr52 variant allozyme, but there was a 40% decrease in the level of activity in cells transfected with the Met108 construct. Apparent Km values of the WT and variant allozymes for the two reaction cosubstrates differed slightly, but significantly, for 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid but not for S-adenosyl-L-methionine. -

Open Matthew R Moreau Ph.D. Dissertation Finalfinal.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Pathobiology Program PATHOGENOMICS AND SOURCE DYNAMICS OF SALMONELLA ENTERICA SEROVAR ENTERITIDIS A Dissertation in Pathobiology by Matthew Raymond Moreau 2015 Matthew R. Moreau Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 The Dissertation of Matthew R. Moreau was reviewed and approved* by the following: Subhashinie Kariyawasam Associate Professor, Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Dissertation Adviser Co-Chair of Committee Bhushan M. Jayarao Professor, Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Dissertation Adviser Co-Chair of Committee Mary J. Kennett Professor, Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Vijay Kumar Assistant Professor, Department of Nutritional Sciences Anthony Schmitt Associate Professor, Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences Head of the Pathobiology Graduate Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis (SE) is one of the most frequent common causes of morbidity and mortality in humans due to consumption of contaminated eggs and egg products. The association between egg contamination and foodborne outbreaks of SE suggests egg derived SE might be more adept to cause human illness than SE from other sources. Therefore, there is a need to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the ability of egg- derived SE to colonize the chicken intestinal and reproductive tracts and cause disease in the human host. To this end, the present study was carried out in three objectives. The first objective was to sequence two egg-derived SE isolates belonging to the PFGE type JEGX01.0004 to identify the genes that might be involved in SE colonization and/or pathogenesis. -

The Microbiota-Produced N-Formyl Peptide Fmlf Promotes Obesity-Induced Glucose

Page 1 of 230 Diabetes Title: The microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide fMLF promotes obesity-induced glucose intolerance Joshua Wollam1, Matthew Riopel1, Yong-Jiang Xu1,2, Andrew M. F. Johnson1, Jachelle M. Ofrecio1, Wei Ying1, Dalila El Ouarrat1, Luisa S. Chan3, Andrew W. Han3, Nadir A. Mahmood3, Caitlin N. Ryan3, Yun Sok Lee1, Jeramie D. Watrous1,2, Mahendra D. Chordia4, Dongfeng Pan4, Mohit Jain1,2, Jerrold M. Olefsky1 * Affiliations: 1 Division of Endocrinology & Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 2 Department of Pharmacology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. 3 Second Genome, Inc., South San Francisco, California, USA. 4 Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. * Correspondence to: 858-534-2230, [email protected] Word Count: 4749 Figures: 6 Supplemental Figures: 11 Supplemental Tables: 5 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online April 22, 2019 Diabetes Page 2 of 230 ABSTRACT The composition of the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota and associated metabolites changes dramatically with diet and the development of obesity. Although many correlations have been described, specific mechanistic links between these changes and glucose homeostasis remain to be defined. Here we show that blood and intestinal levels of the microbiota-produced N-formyl peptide, formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF), are elevated in high fat diet (HFD)- induced obese mice. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of the N-formyl peptide receptor Fpr1 leads to increased insulin levels and improved glucose tolerance, dependent upon glucagon- like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Obese Fpr1-knockout (Fpr1-KO) mice also display an altered microbiome, exemplifying the dynamic relationship between host metabolism and microbiota. -

Product Sheet Info

Master Clone List for NR-19279 ® Vibrio cholerae Gateway Clone Set, Recombinant in Escherichia coli, Plates 1-46 Catalog No. NR-19279 Table 1: Vibrio cholerae Gateway® Clones, Plate 1 (NR-19679) Clone ID Well ORF Locus ID Symbol Product Accession Position Length Number 174071 A02 367 VC2271 ribD riboflavin-specific deaminase NP_231902.1 174346 A03 336 VC1877 lpxK tetraacyldisaccharide 4`-kinase NP_231511.1 174354 A04 342 VC0953 holA DNA polymerase III, delta subunit NP_230600.1 174115 A05 388 VC2085 sucC succinyl-CoA synthase, beta subunit NP_231717.1 174310 A06 506 VC2400 murC UDP-N-acetylmuramate--alanine ligase NP_232030.1 174523 A07 132 VC0644 rbfA ribosome-binding factor A NP_230293.2 174632 A08 322 VC0681 ribF riboflavin kinase-FMN adenylyltransferase NP_230330.1 174930 A09 433 VC0720 phoR histidine protein kinase PhoR NP_230369.1 174953 A10 206 VC1178 conserved hypothetical protein NP_230823.1 174976 A11 213 VC2358 hypothetical protein NP_231988.1 174898 A12 369 VC0154 trmA tRNA (uracil-5-)-methyltransferase NP_229811.1 174059 B01 73 VC2098 hypothetical protein NP_231730.1 174075 B02 82 VC0561 rpsP ribosomal protein S16 NP_230212.1 174087 B03 378 VC1843 cydB-1 cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase, subunit II NP_231477.1 174099 B04 383 VC1798 eha eha protein NP_231433.1 174294 B05 494 VC0763 GTP-binding protein NP_230412.1 174311 B06 314 VC2183 prsA ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase NP_231814.1 174603 B07 108 VC0675 thyA thymidylate synthase NP_230324.1 174474 B08 466 VC1297 asnS asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase NP_230942.2 174933 B09 198 -

EZH2 in Normal Hematopoiesis and Hematological Malignancies

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 7, No. 3 EZH2 in normal hematopoiesis and hematological malignancies Laurie Herviou2, Giacomo Cavalli2, Guillaume Cartron3,4, Bernard Klein1,2,3 and Jérôme Moreaux1,2,3 1 Department of Biological Hematology, CHU Montpellier, Montpellier, France 2 Institute of Human Genetics, CNRS UPR1142, Montpellier, France 3 University of Montpellier 1, UFR de Médecine, Montpellier, France 4 Department of Clinical Hematology, CHU Montpellier, Montpellier, France Correspondence to: Jérôme Moreaux, email: [email protected] Keywords: hematological malignancies, EZH2, Polycomb complex, therapeutic target Received: August 07, 2015 Accepted: October 14, 2015 Published: October 20, 2015 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb repressive complex 2, inhibits gene expression through methylation on lysine 27 of histone H3. EZH2 regulates normal hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. EZH2 also controls normal B cell differentiation. EZH2 deregulation has been described in many cancer types including hematological malignancies. Specific small molecules have been recently developed to exploit the oncogenic addiction of tumor cells to EZH2. Their therapeutic potential is currently under evaluation. This review summarizes the roles of EZH2 in normal and pathologic hematological processes and recent advances in the development of EZH2 inhibitors for the personalized treatment of patients with hematological malignancies. PHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS OF EZH2 state through tri-methylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) [6]. -

The Metabolic Building Blocks of a Minimal Cell Supplementary

The metabolic building blocks of a minimal cell Mariana Reyes-Prieto, Rosario Gil, Mercè Llabrés, Pere Palmer and Andrés Moya Supplementary material. Table S1. List of enzymes and reactions modified from Gabaldon et. al. (2007). n.i.: non identified. E.C. Name Reaction Gil et. al. 2004 Glass et. al. 2006 number 2.7.1.69 phosphotransferase system glc + pep → g6p + pyr PTS MG041, 069, 429 5.3.1.9 glucose-6-phosphate isomerase g6p ↔ f6p PGI MG111 2.7.1.11 6-phosphofructokinase f6p + atp → fbp + adp PFK MG215 4.1.2.13 fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase fbp ↔ gdp + dhp FBA MG023 5.3.1.1 triose-phosphate isomerase gdp ↔ dhp TPI MG431 glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate gdp + nad + p ↔ bpg + 1.2.1.12 GAP MG301 dehydrogenase nadh 2.7.2.3 phosphoglycerate kinase bpg + adp ↔ 3pg + atp PGK MG300 5.4.2.1 phosphoglycerate mutase 3pg ↔ 2pg GPM MG430 4.2.1.11 enolase 2pg ↔ pep ENO MG407 2.7.1.40 pyruvate kinase pep + adp → pyr + atp PYK MG216 1.1.1.27 lactate dehydrogenase pyr + nadh ↔ lac + nad LDH MG460 1.1.1.94 sn-glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase dhp + nadh → g3p + nad GPS n.i. 2.3.1.15 sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase g3p + pal → mag PLSb n.i. 2.3.1.51 1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate mag + pal → dag PLSc MG212 acyltransferase 2.7.7.41 phosphatidate cytidyltransferase dag + ctp → cdp-dag + pp CDS MG437 cdp-dag + ser → pser + 2.7.8.8 phosphatidylserine synthase PSS n.i. cmp 4.1.1.65 phosphatidylserine decarboxylase pser → peta PSD n.i. -

Structure and Mechanism of a Eukaryotic Fmn Adenylyltransferase

STRUCTURE AND MECHANISM OF A EUKARYOTIC FMN ADENYLYLTRANSFERASE Approved by supervisory committee ____________________________________ Hong Zhang, Ph.D. (Mentor) ____________________________________ Diana Tomchick, Ph.D. (Committee Chair) ____________________________________ Kevin Gardner, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Betsy Goldsmith, Ph.D. This thesis is dedicated to my family. STRUCTURE AND MECHANISM OF A EUKARYOTIC FMN ADENYLYLTRANSFERASE by CARLOS HUERTA JR. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Dallas, Texas December, 2009 Copyright by CARLOS HUERTA JR., 2009 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many individuals that contributed to my graduate education and I would like to thank a few of them. First, I would like to honor my mentor, Dr. Hong Zhang. Dr. Zhang’s support and encouragement was essential to the completion of my graduate education. Dr. Zhang’s compassion to X-ray crystallography and biological science was fundamental in transforming me into a structural biologist. I would also like to thank all past and current members of the Zhang laboratory. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Nian Huang and Dr. Darek Martynowski for discussions in structure refinement and modeling, and Marcelo Raines for teaching me protein purification and crystallization. A special acknowledgement goes to Dr. Dominika Borek for teaching me how to solve my first protein structure and her support through-out my graduate education. My graduate thesis would not be possible without the guidance and understanding of my dissertation committee members Dr. -

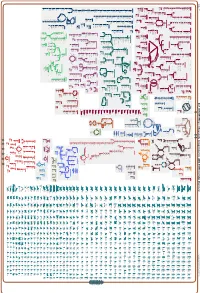

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Ron Caspi Peter Midford Peter D Karp An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Ingrid Keseler Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Gcf_003855395Cyc: Shewanella livingstonensis LMG 19866 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. -

The Importance of Study Design Abundant Features in High

The importance of study design for detecting differentially abundant features in high -throughput experiments Luo Huaien 1* , Li Juntao 1*, C hia Kuan Hui Burton 1, Paul Robson 2, Niranjan Nagarajan 1# a b c d Supplementary Figure 1. Variability in performance across DATs with few repreplicates.licates. The subfigures depict precision-recall tradeoffs for DATs, under a range of experimexperimenentaltal conditions and with few replicates (2 in this case). The following parameters were used in EDDA for the sub figures: (a) PDA=30% and FC=Uniform[2,6] (b) as in subfigure (a) but with AP=HBR (c) PDA= [15% UP, 30% DOWN] and FC=Uniform[3,15] (d) PDA=[50% UP, 25% DOWN], FC=Normal[5,1.33] and SM=Full. Common parameters unless otherwise stated include AP=BP, EC=1000, ND=500 per entity, SM=NB and SV=0.5. a b c d Supplementary Figure 2 . Variability in performance across DATs with few data -points. Note that as in Supplementary Figure 1 , the performance of DATs varies widely merely by changing the number of replicates from 1 to 4 in sub figures (a)-(d) in a situation where the number data -points generated is limited (only 50 on average per entity). Results reported are based on data generated in EDDA with the following parameters (roughly mimicking a microbial RNA-seq application) : EC=1000, PDA=26%, FC=Uniform[3,7 ], AP=BP, SM=Full and SV=0.85. Supplementary Figure 3. Distribution of relative abundance in different empirically derived profiles. Note that both axes are plotted on a log-scale and that while BP does not have entities with relative abundance < 1e-5, the profile from Wu et al is more enriched for entities with relative abundance < 1e-5 than the HBR profile. -

Expanding the Structural Diversity of DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors

pharmaceuticals Article Expanding the Structural Diversity of DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors K. Eurídice Juárez-Mercado 1 , Fernando D. Prieto-Martínez 1 , Norberto Sánchez-Cruz 1 , Andrea Peña-Castillo 1, Diego Prada-Gracia 2 and José L. Medina-Franco 1,* 1 DIFACQUIM Research Group, Department of Pharmacy, School of Chemistry, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Avenida Universidad 3000, Mexico City 04510, Mexico; [email protected] (K.E.J.-M.); [email protected] (F.D.P.-M.); [email protected] (N.S.-C.); [email protected] (A.P.-C.) 2 Research Unit on Computational Biology and Drug Design, Children’s Hospital of Mexico Federico Gomez, Mexico City 06720, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are attractive compounds for epigenetic drug discovery. They are also chemical tools to understand the biochemistry of epigenetic processes. Herein, we report five distinct inhibitors of DNMT1 characterized in enzymatic inhibition assays that did not show activity with DNMT3B. It was concluded that the dietary component theaflavin is an inhibitor of DNMT1. Two additional novel inhibitors of DNMT1 are the approved drugs glyburide and panobinostat. The DNMT1 enzymatic inhibitory activity of panobinostat, a known pan inhibitor of histone deacetylases, agrees with experimental reports of its ability to reduce DNMT1 activity in liver cancer cell lines. Molecular docking of the active compounds with DNMT1, and re-scoring with the recently developed extended connectivity interaction features approach, led to an excellent agreement between the experimental IC50 values and docking scores. Citation: Juárez-Mercado, K.E.; Keywords: dietary component; epigenetics; enzyme inhibition; focused library; epi-informatics; Prieto-Martínez, F.D.; Sánchez-Cruz, multitarget epigenetic agent; natural products; chemoinformatics N.; Peña-Castillo, A.; Prada-Gracia, D.; Medina-Franco, J.L. -

The Action Mechanism of Prokaryotic FAD Synthetases As a Potential Drug Target for the Treatment of Bacterial Infections

2018 112 María Sebastián Valverde The action mechanism of prokaryotic FAD synthetases as a potential drug target for the treatment of bacterial infections Departamento Bioquímica y Biología Molecular y Celular Director/es MEDINA TRULLENQUE, MILAGROS Reconocimiento – NoComercial – © Universidad de Zaragoza SinObraDerivada (by-nc-nd): No se Servicio de Publicaciones permite un uso comercial de la obra original ni la generación de obras derivadas. ISSN 2254-7606 Tesis Doctoral THE ACTION MECHANISM OF PROKARYOTIC FAD SYNTHETASES AS A POTENTIAL DRUG TARGET FOR THE TREATMENT OF BACTERIAL INFECTIONS Autor María Sebastián Valverde Director/es MEDINA TRULLENQUE, MILAGROS UNIVERSIDAD DE ZARAGOZA Bioquímica y Biología Molecular y Celular 2018 Repositorio de la Universidad de Zaragoza – Zaguan http://zaguan.unizar.es Abstract 1 Resumen 7 Chapter I: Introduction 13 1. The need of new antibacterial targets 15 1.1. From the beginnings to the golden era in the development of antibiotics 15 1.2. The resistance era put in check our effectiveness against pathogens 16 1.3. What makes a drug target good? 17 1.4. Proteins involved in flavins synthesis are promising drug targets 18 2. Flavins and flavoproteins: past, present and properties 20 2.1. A brief history of flavins and flavoproteins 20 2.2. Flavins are heterocyclic molecules 21 2.3. Flavins exhibit versatile redox properties 23 2.4. Flavins show useful spectroscopic properties 24 2.4.1. Absorption in the UV depends on the redox state 24 2.4.2. Flavins are fluorescent compounds 26 2.5. Biosynthesis of FMN and FAD in different organisms 26 3. FMN and FAD biosynthesis in different types of organisms 27 3.1.