Taxonomy, Life History, and Ecology of a Mountain-Mahogany Defoliator, Stamnodes Animata (Pearsail), in Nevada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Appendix C Botanical Resources Table of Contents Purpose Of This Appendix ............................................................................................................. Below Tables C-1. Federal and State Status, Current and Proposed Forest Service Status, and Global Distribution of the TEPCS Plant Species on the Sawtooth National Forest ........................... C-1 C-2. Habit, Lifeform, Population Trend, and Habitat Grouping of the TEPCS Plant Species for the Sawtooth National Forest ............................................................................... C-3 C-3. Rare Communities, Federal and State Status, Rarity Class, Threats, Trends, and Research Natural Area Distribution for the Sawtooth National Forest ................................... C-5 C-4. Plant Species of Cultural Importance for the Sawtooth National Forest ................................... C-6 PURPOSE OF THIS APPENDIX This appendix is designed to provide detailed information about habitat, lifeform, status, distribution, and habitat grouping for the Threatened, Proposed, Candidate, and Sensitive (current and proposed) plant species found on the Sawtooth National Forest. The detailed information is provided to enable managers to more efficiently direct the implementation of Botanical Resources goals, objectives, standards, and guidelines. Additionally, this appendix provides detailed information about the rare plant communities located on the Sawtooth National Forest and should provide additional support of Forest-wide objectives. Species of cultural -

P L a N T L I S T Water-Wise Trees and Shrubs for the High Plains

P L A N T L I S T Water-Wise Trees and Shrubs for the High Plains By Steve Scott, Cheyenne Botanic Gardens Horticulturist 03302004 © Cheyenne Botanic Gardens 2003 710 S. Lions Park Dr., Cheyenne WY, 82001 www.botanic.org The following is a list of suitable water-wise trees and shrubs that are suitable for water- wise landscaping also known as xeriscapes. Many of these plants may suffer if they are placed in areas receiving more than ¾ of an inch of water per week in summer. Even drought tolerant trees and shrubs are doomed to failure if grasses or weeds are growing directly under and around the plant, especially during the first few years. It is best to practice tillage, hoeing, hand pulling or an approved herbicide to kill all competing vegetation for the first five to eight years of establishment. Avoid sweetening the planting hole with manure or compost. If the soil is needs improvement, improve the whole area, not just the planting hole. Trees and shrubs generally do best well with no amendments. Many of the plants listed here are not available in department type stores. Your best bets for finding these plants will be in local nurseries- shop your hometown first! Take this list with you. Encourage nurseries and landscapers to carry these plants! For more information on any of these plants please contact the Cheyenne Botanic Gardens (307-637-6458), the Cheyenne Forestry Department (307-637-6428) or your favorite local nursery. CODE KEY- The code key below will assist you in selecting for appropriate characteristics. -

Lonicera Spp

Species: Lonicera spp. http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/lonspp/all.html SPECIES: Lonicera spp. Choose from the following categories of information. Introductory Distribution and occurrence Botanical and ecological characteristics Fire ecology Fire effects Fire case studies Management considerations References INTRODUCTORY SPECIES: Lonicera spp. AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION SYNONYMS NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY LIFE FORM FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS OTHER STATUS AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Munger, Gregory T. 2005. Lonicera spp. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2007, September 24]. FEIS ABBREVIATIONS: LONSPP LONFRA LONMAA LONMOR LONTAT LONXYL LONBEL SYNONYMS: None NRCS PLANT CODES [172]: LOFR LOMA6 LOMO2 LOTA LOXY 1 of 67 9/24/2007 4:44 PM Species: Lonicera spp. http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/lonspp/all.html LOBE COMMON NAMES: winter honeysuckle Amur honeysuckle Morrow's honeysuckle Tatarian honeysuckle European fly honeysuckle Bell's honeysuckle TAXONOMY: The currently accepted genus name for honeysuckle is Lonicera L. (Caprifoliaceae) [18,36,54,59,82,83,93,133,161,189,190,191,197]. This report summarizes information on 5 species and 1 hybrid of Lonicera: Lonicera fragrantissima Lindl. & Paxt. [36,82,83,133,191] winter honeysuckle Lonicera maackii Maxim. [18,27,36,54,59,82,83,131,137,186] Amur honeysuckle Lonicera morrowii A. Gray [18,39,54,60,83,161,186,189,190,197] Morrow's honeysuckle Lonicera tatarica L. [18,38,39,54,59,60,82,83,92,93,157,161,186,190,191] Tatarian honeysuckle Lonicera xylosteum L. -

Universidad Nacional Mayor De San Marcos Universidad Del Perú

Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Universidad del Perú. Decana de América Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas Escuela Profesional de Ciencias Biológicas Aplicación del código de barras de ADN en la identificación de insectos fitófagos asociados al cultivo de quinua (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) en Perú TESIS Para optar el Título Profesional de Biólogo con mención en Zoología AUTOR Nilver Jhon ZENTENO GUILLERMO ASESOR Dra. Diana Fernanda SILVA DÁVILA Lima, Perú 2019 DEDICATORIA A mis padres, Juan Clemente Zenteno Rodriguez y Leyda Eddy Guillermo Chávez por su apoyo incondicional y cariño a lo largo de esta aventura en mi vida. Jamás terminaré de agradecerles por todo. AGRADECIMIENTOS La vida me ha dado muchas cosas durante mi breve permanencia en este planeta, cosas para las cuales, unas cuantas palabras no bastarán para poder expresar cuan agradecido estoy. En primera instancia quiero dar gracias a mis padres Juan y Leyda y a mis hermanos Dennis y Jhovani por todo su cariño y apoyo. A mi asesora de tesis, la Dra. Diana Silva Dávila por su gran paciencia durante toda la etapa desde el proyecto hasta la tesis concluida. Al proyecto PNIA N° 038-2015-INIA-PNIA/UPMSI/IE “Optimización de la identificación de plagas entomológicas en cultivos de importancia económica mediante código de barras de ADN y construcción de base de datos” por el financiamiento que hizo posible el presente estudio. A la Dra. Ida Bartolini, al Blgo. Arturo Olortegui, y a la Blga. Rosalyn Acuña por su ayuda y guía en los procesamientos moleculares de las muestras de especímenes en el laboratorio de Biología Molecular de la Unidad del Centro de Diagnóstico de Sanidad Vegetal del Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agraria. -

CDFG Natural Communities List

Department of Fish and Game Biogeographic Data Branch The Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program List of California Terrestrial Natural Communities Recognized by The California Natural Diversity Database September 2003 Edition Introduction: This document supersedes all other lists of terrestrial natural communities developed by the Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB). It is based on the classification put forth in “A Manual of California Vegetation” (Sawyer and Keeler-Wolf 1995 and upcoming new edition). However, it is structured to be compatible with previous CNDDB lists (e.g., Holland 1986). For those familiar with the Holland numerical coding system you will see a general similarity in the upper levels of the hierarchy. You will also see a greater detail at the lower levels of the hierarchy. The numbering system has been modified to incorporate this richer detail. Decimal points have been added to separate major groupings and two additional digits have been added to encompass the finest hierarchal detail. One of the objectives of the Manual of California Vegetation (MCV) was to apply a uniform hierarchical structure to the State’s vegetation types. Quantifiable classification rules were established to define the major floristic groups, called alliances and associations in the National Vegetation Classification (Grossman et al. 1998). In this document, the alliance level is denoted in the center triplet of the coding system and the associations in the right hand pair of numbers to the left of the final decimal. The numbers of the alliance in the center triplet attempt to denote relationships in floristic similarity. For example, the Chamise-Eastwood Manzanita alliance (37.106.00) is more closely related to the Chamise- Cupleaf Ceanothus alliance (37.105.00) than it is to the Chaparral Whitethorn alliance (37.205.00). -

F.3 References for Appendix F

F-1 APPENDIX F: ECOREGIONS OF THE 11 WESTERN STATES AND DISTRIBUTION BY ECOREGION OF WIND ENERGY RESOURCES ON BLM-ADMINISTERED LANDS WITHIN EACH STATE F-2 F-3 APPENDIX F: ECOREGIONS OF THE 11 WESTERN STATES AND DISTRIBUTION BY ECOREGION OF WIND ENERGY RESOURCES ON BLM-ADMINISTERED LANDS WITHIN EACH STATE F.1 DESCRIPTIONS OF THE ECOREGIONS Ecoregions delineate areas that have a general similarity in their ecosystems and in the types, qualities, and quantities of their environmental resources. They are based on unique combinations of geology, physiography, vegetation, climate, soils, land use, wildlife, and hydrology (EPA 2004). Ecoregions are defined as areas having relative homogeneity in their ecological systems and their components. Factors associated with spatial differences in the quality and quantity of ecosystem components (including soils, vegetation, climate, geology, and physiography) are relatively homogeneous within an ecoregion. A number of individuals and organizations have characterized North America on the basis of ecoregions (e.g., Omernik 1987; CEC 1997; Bailey 1997). The intent of such ecoregion classifications has been to provide a spatial framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and ecosystem components. The ecoregion discussions presented in this programmatic environmental impact statement (PEIS) follow the Level III ecoregion classification based on Omernik (1987) and refined through collaborations among U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regional offices, state resource management agencies, and other federal agencies (EPA 2004). The following sections provide brief descriptions of each of the Level III ecoregions that have been identified for the 11 western states in which potential wind energy development may occur on BLM-administered lands. -

Cercocarpus Montanus Cercocarpus Montanus ‘USU-CEMO-001’ ‘USU-CEMO- Was Collected As a Suspected Dwarf Plant in TM Moffat County, CO, on 20 June 2014

HORTSCIENCE 55(11):1871–1875. 2020. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI15343-20 Origin Cercocarpus montanus Cercocarpus montanus ‘USU-CEMO-001’ ‘USU-CEMO- was collected as a suspected dwarf plant in TM Moffat County, CO, on 20 June 2014. This 001’: A New Sego Supreme Plant unique, procumbent specimen was discovered laying over a rock on a windy ridge at an Asmita Paudel, Youping Sun, and Larry A. Rupp elevation of 2708 m (Fig. 2A). The appearance Center for Water Efficient Landscaping, Department of Plants, Soils, and looked different from the typical C. montanus Climate, Utah State University, 4820 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT 84322 nearby (Fig. 2B). The leaves are smaller and narrower with less serrations compared with Richard Anderson the typical plants (Fig. 2C). Healthy cuttings USU Botanical Center, 725 Sego Lily Drive, Kaysville, UT 84037 were collected, wrapped in moist newspapers and placed on ice until transferred to a cooler at Additional index words. alder-leaf mountain mahogany, cutting propagation, landscape plant, 4 °C. On 21 June, the terminal cuttings were native plant, true mountain mahogany rinsed in 1% ZeroTol (27.1% hydrogen diox- ide, 2.0% peroxyacetic acid, 70.9% inert in- gredient; BioSafe Systems, Hartford, CT), Sego SupremeTM is a plant introduction mose style with elongated achenes wounded by scraping 1 cm of bark from the program developed by the Utah State Uni- (Fig. 1B) (Shaw et al., 2004). It possesses base of the cutting on one side, treated with versity (USU) Botanical Center (Anderson an extensive root system and adapts to 2000 mg·L–1 indole-3-butyric acid (IBA)/1000 et al., 2014) to introduce native and adaptable medium to coarse textured soil. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

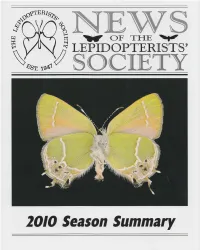

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory ........................................................................................... 3 Alaska ... ........................................ ............................................................... 3 LEPIDOPTERISTS Zone 2: British Columbia .................................................... ........................ ............ 6 Idaho .. ... ....................................... ................................................................ 6 Oregon ........ ... .... ........................ .. .. ............................................................ 10 SOCIETY Volume 53 Supplement Sl Washington ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3: Arizona ............................................................ .................................... ...... 19 The Lepidopterists' Society is a non-profo California ............... ................................................. .............. .. ................... 2 2 educational and scientific organization. The Nevada ..................................................................... ................................ 28 object of the Society, which was formed in Zone 4: Colorado ................................ ... ............... ... ...... ......................................... 2 9 May 1947 and formally constituted in De Montana .................................................................................................... 51 cember -

Peoyincial Museum

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA REPORT OF THE PEOYINCIAL MUSEUM NATURAL HISTORY FOR THE TEAR 1918 PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C.: Printed by WILLIAM H. CULLICN, Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty, 1919. To His Honour Sir FRANK STILLMAN BARNARD, K.C.M.G., Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: The undersigned respectfully submits the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History for the year 1918. j. D. MACLEAN, Provincial Secretary. Provincial Secretary's Office, Victoria, March 7th, 1919. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, VICTORIA, B.C., March 7th, 1919. The Honourable J. D. MacLean, M.D., Provincial Secretary, Victoria, B.C. SIR,—I have the honour, as Director of the Provincial Museum of Natural History, to lay before you the Keport for the year ending December 31st, 1918, covering the activities of the Museum. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, PKANCIS KERMODE, Director. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1918. Since the last Annual Report, although no actual field-work was undertaken, a great deal of time was devoted to the study collection in going through the specimens which have been collected from time to time and are stored in the annex. All the specimens have been rearranged, labelled, and listed, so as to make them more accessible to those who wish to consult them in the several branches of natural sciences. In this building, which is not in any way fire-proof, is stored a very large and valuable collection of anthropological material, which, if it were to be destroyed by fire, would be impossible to duplicate; this also applies to a large number of totem-poles in the basement under this building. -

Historical Vegetation of Central Southwest Oregon, Based on GLO

HISTORICAL VEGETATION OF CENTRAL SOUTHWEST OREGON, BASED ON GLO SURVEY NOTES Final Report to USDI BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Medford District October 31, 2011 By O. Eugene Hickman and John A. Christy Consulting Rangeland Ecologist Oregon Biodiversity Information Center Retired, USDA - NRCS Portland State University 61851 Dobbin Road PSU – INR, P.O. Box 751 Bend, Oregon 97702 Portland, Oregon 97207-0751 (541, 312-2512) (503, 725-9953) [email protected] [email protected] Suggested citation: Hickman, O. Eugene and John A. Christy. 2011. Historical Vegetation of Central Southwest Oregon Based on GLO Survey Notes. Final Report to USDI Bureau of Land Management. Medford District, Oregon. 124 pp. ______________________________________________________________________________ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 SW OREGON PRE-GLO SURVEY HISTORY ....................................................................................................................... 7 THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE, ITS FUNCTION AND HISTORY........................................................................................... -

Reference Plant List

APPENDIX J NATIVE & INVASIVE PLANT LIST The following tables capture the referenced plants, native and invasive species, found throughout this document. The Wildlife Action Plan Team elected to only use common names for plants to improve the readability, particular for the general reader. However, common names can create confusion for a variety of reasons. Common names can change from region-to-region; one common name can refer to more than one species; and common names have a way of changing over time. For example, there are two widespread species of greasewood in Nevada, and numerous species of sagebrush. In everyday conversation generic common names usually work well. But if you are considering management activities, landscape restoration or the habitat needs of a particular wildlife species, the need to differentiate between plant species and even subspecies suddenly takes on critical importance. This appendix provides the reader with a cross reference between the common plant names used in this document’s text, and the scientific names that link common names to the precise species to which writers referenced. With regards to invasive plants, all species listed under the Nevada Revised Statute 555 (NRS 555) as a “Noxious Weed” will be notated, within the larger table, as such. A noxious weed is a plant that has been designated by the state as a “species of plant which is, or is likely to be, detrimental or destructive and difficult to control or eradicate” (NRS 555.05). To assist the reader, we also included a separate table detailing the noxious weeds, category level (A, B, or C), and the typical habitats that these species invade.