Henry Steele Commager As Historian and Public Intellectual[1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings 207

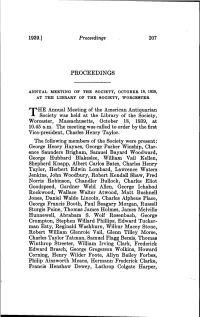

1939.] Proceedings 207 PROCEEDINGS ANNUAL MEETING OP THE SOCIETY, OCTOBER 18, 1939, AT THE LIBEARY OF THE SOCIETY, WORCESTER Annual Meeting of the Anierican Antiquarian -1 Society was held at the Library of the Society, Worcester, Massachusetts, October 18, 1939, at 10.45 a.m. The meeting was called to order by the first Vice-president, Charles Henry Taylor. The following members of the Society were present : George Henry Haynes, George Parker Winship, Clar- ence Saunders Brigham, Samuel Bayard Woodward, George Hubbard Blakeslee, William Vail Kellen, Shepherd Knapp, Albert Carlos Bates, Charles Henry Taylor, Herbert Edwin Lombard, Lawrence Waters Jenkins, John Woodbury, Robert Kendall Shaw, Fred Norris Robinson, Chandler BuUockj Charles Eliot Goodspeed, Gardner Weld Allen, George Ichabod Rockwood, Wallace Walter Atwood, Matt Bushneil Jones, Daniel Waldo Lincoln, Charles Alpheus Place, George Francis Booth, Paul Beagary Morgan, Russell Sturgis Paine, Thomas James Holmes, James Melville Hunnewell, Abraham S. Wolf Rosenbach, George Crompton, Stephen Willard Phillips, Edward Tucker- man Esty, Reginald Washburn, Wilbur Macey Stone, Robert William Glenroie Vail, Glenn Tilley Morse, Charles Taylor Tatman, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Thomas Winthrop Streeter, William Irving Clark, Frederick Edward Brasch, George Gregerson Wolkins, Howard Corning, Henry Wilder Foote, Allyn Bailey Forbes, Philip Ainsworth Means, Hermann Frederick Clarke, Francis Henshaw Dewey, Lathrop Colgate Harper, 208 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., Augustus Peabody Loring, Jr., James Duncan Phillips, Clifford Kenyon Shipton, Alexander Hamilton Bullock, Theron Johnson Damon, Albert White Rice, Fred- erick Lewis Weis, Donald McKay Frost, Harry- Andrew Wright. It was voted to dispense with the reading of the records of the last meeting. The report of the Council of the Society was presented by the Director, Mr. -

Bernstein on Jumonville, 'Henry Steele Commager: Midcentury Liberalism and the History of the Present'

H-Law Bernstein on Jumonville, 'Henry Steele Commager: Midcentury Liberalism and the History of the Present' Review published on Friday, October 1, 1999 Neil Jumonville. Henry Steele Commager: Midcentury Liberalism and the History of the Present. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999. xviii + 328 pp. $49.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8078-2448-1. Reviewed by R. B. Bernstein (New York Law School) Published on H-Law (October, 1999) Scholarship and Engagement: Henry Steele Commager as Historian and Public Intellectual[1] In December of 1998, midway through the House Judiciary Committee's hearings on the impeachment of President Clinton, the Committee called as witnesses a panel of historians and legal scholars who sought to cast light on the history and purposes of the impeachment process. Members of the H-LAW community would have recognized such names as Bruce Ackerman of Yale Law School, Jack N. Rakove of Stanford, and Sean Wilentz of Princeton. The odd thing about this panel, and about the other efforts of historians and other scholars to take part in the public controversy about impeachment, was that they either seemed or were treated as being out of place. Indeed, in his new book on the impeachment controversy, Judge Richard A. Posner argues that one lesson of the Clinton impeachment is just how unsuited historians are to offer guidance on matters of public policy.[2] Twenty-five years before this puzzling episode, the nation was roiled by another crisis posing the risk of Presidential impeachment--the Watergate controversy that finally drove President Richard Nixon to resign his office. -

University Microfilms Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All

8404787 Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-1900 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Middle Tennessee State University D.A. 1983 University Microfilms Internet ion elæ o N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. Problems encountered with this document have been identified here with a check mark V 1. Glossy photographs or pages. 2. Colored illustrations, paper or print_____ 3. Photographs with dark background_____ 4. Illustrations are poor copy______ 5. Pages with black marks, not original copy_ 6. Print shows through as there is text on both sides of page. 7. Indistinct, broken or small print on several pages______ 8. Print exceeds margin requirements______ 9. Tightly bound copy with print lost in spine______ 10. Computer printout pages with indistinct print. 11. Page(s)____________ lacking when material received, and not available from school or author. 12. Page(s) 18 seem to be missing in numbering only as text follows. 13. Two pages numbered _______iq . Text follows. 14. Curling and wrinkled pages______ 15. Other ________ University Microfilms International Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-190 0 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Reavis Lee Mitchell, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Arts December, 1983 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

I^Igtorical ^Siisociation

American i^igtorical ^siisociation SEVENTY-SECOND ANNUAL MEETING NEW YORK HEADQUARTERS: HOTEL STATLER DECEMBER 28, 29, 30 Bring this program with you Extra copies 25 cents Please be certain to visit the hook exhibits The Culture of Contemporary Canada Edited by JULIAN PARK, Professor of European History and International Relations at the University of Buffalo THESE 12 objective essays comprise a lively evaluation of the young culture of Canada. Closely and realistically examined are literature, art, music, the press, theater, education, science, philosophy, the social sci ences, literary scholarship, and French-Canadian culture. The authors, specialists in their fields, point out the efforts being made to improve and consolidate Canada's culture. 419 Pages. Illus. $5.75 The American Way By DEXTER PERKINS, John L. Senior Professor in American Civilization, Cornell University PAST and contemporary aspects of American political thinking are illuminated by these informal but informative essays. Professor Perkins examines the nature and contributions of four political groups—con servatives, liberals, radicals, and socialists, pointing out that the continu ance of healthy, active moderation in American politics depends on the presence of their ideas. 148 Pages. $2.75 A Short History of New Yorh State By DAVID M.ELLIS, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, Harry J. Carman HERE in one readable volume is concise but complete coverage of New York's complicated history from 1609 to the present. In tracing the state's transformation from a predominantly agricultural land into a rich industrial empire, four distinguished historians have drawn a full pic ture of political, economic, social, and cultural developments, giving generous attention to the important period after 1865. -

Department of History University of New Hampshire

DRAFT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE History 939 Professor Eliga Gould Fall 2015 Office: Horton 423B T 8:40-9:30 Phone: 862-3012 Horton 422 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: T 9:30-11:30 and by appointment Readings in Early American History Assigned Readings. (Unless otherwise noted, all titles are available at the University Bookstore and the Durham Book Exchange.) Bailyn, Bernard. Atlantic History: Concept and Contours (2005) Berlin, Ira. Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (2000). Bushman, Richard. The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (1992). Cronon, William. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England (1983) Gould, Eliga H. Among the Powers of the Earth: The American Revolution and the Making of a New World Empire (2012) Greene, Jack P., and Philip D. Morgan. Atlantic History: A Critical Appraisal (2008). Hall, David D. Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgment: Popular Religious Belief in Early New England (1989). Johnson, Walter. River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (2013). Lepler, Jessica. The Many Panics of 1837: People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis (2013). McPherson, James. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988). Morgan, Edmund S. and Helen M. The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (1953). Richter, Daniel. Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America (2001). Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812 (1990). Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1993). -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Ralph H. Records Collection Records, Ralph Hayden. Papers, 1871–1968. 2 feet. Professor. Magazine and journal articles (1946–1968) regarding historiography, along with a typewritten manuscript (1871–1899) by L. S. Records, entitled “The Recollections of a Cowboy of the Seventies and Eighties,” regarding the lives of cowboys and ranchers in frontier-era Kansas and in the Cherokee Strip of Oklahoma Territory, including a detailed account of Records’s participation in the land run of 1893. ___________________ Box 1 Folder 1: Beyond The American Revolutionary War, articles and excerpts from the following: Wilbur C. Abbott, Charles Francis Adams, Randolph Greenfields Adams, Charles M. Andrews, T. Jefferson Coolidge, Jr., Thomas Anburey, Clarence Walroth Alvord, C.E. Ayres, Robert E. Brown, Fred C. Bruhns, Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard, Benjamin Franklin, Carl Lotus Belcher, Henry Belcher, Adolph B. Benson, S.L. Blake, Charles Knowles Bolton, Catherine Drinker Bowen, Julian P. Boyd, Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Sanborn C. Brown, William Hand Browne, Jane Bryce, Edmund C. Burnett, Alice M. Baldwin, Viola F. Barnes, Jacques Barzun, Carl Lotus Becker, Ruth Benedict, Charles Borgeaud, Crane Brinton, Roger Butterfield, Edwin L. Bynner, Carl Bridenbaugh Folder 2: Douglas Campbell, A.F. Pollard, G.G. Coulton, Clarence Edwin Carter, Harry J. Armen and Rexford G. Tugwell, Edward S. Corwin, R. Coupland, Earl of Cromer, Harr Alonzo Cushing, Marquis De Shastelluz, Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Mellen Chamberlain, Dora Mae Clark, Felix S. Cohen, Verner W. Crane, Thomas Carlyle, Thomas Cromwell, Arthur yon Cross, Nellis M. Crouso, Russell Davenport Wallace Evan Daview, Katherine B. -

American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: an Appraisal of Alexis De Tocqueville’S Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and the Post-World War II Welfare State John P. Varacalli The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1828 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] AMERICAN CIVIL ASSOCIATIONS AND THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN GOVERNMENT: AN APPRAISAL OF ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE’S DEMOCRACY IN AMERICA (1835- 1840) APPLIED TO FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S NEW DEAL AND THE POST-WORLD WAR II WELFARE STATE by JOHN P. VARACALLI A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 JOHN P. VARACALLI All Rights Reserved ii American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Post World War II Welfare State by John P. Varacalli The manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ______________________ __________________________________________ Date David Gordon Thesis Advisor ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Acting Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT American Civil Associations and the Growth of American Government: An Appraisal of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835-1840) Applied to Franklin D. -

20 American Antiquarian Society Lications of American Writers. One

20 American Antiquarian Society lications of American writers. One of his earliest catalogues was devoted to these early efforts and this has been followed at intervals by others in the same vein. This was, however, only one facet of his interests and the scholarly catalogues he published covering fiction, poetry, drama, and bibliographical works provide a valuable commentary on the history and the changing fashions of American book buying over four de- cades. The shop established on the premises at S West Forty- sixth Street in New York by Kohn and Papantonio shortly after the end of the war has become a mecca for bibliophiles from all over the United States and from foreign countries. It is not overstating the case to say that Kohn became the leading authority on first and important editions of American literature. He was an interested and active member of the American Antiquarian Society. The Society's incomparable holdings in American literature have been enriched by his counsel and his gifts. He will be sorely missed as a member, a friend, and a benefactor. C. Waller Barrett SAMUEL ELIOT MORISON Samuel Eliot Morison was born in Boston on July 9, 1887, and died there nearly eighty-nine years later on May 15, 1976. He lived most of his life at 44 Brimmer Street in Bos- ton. He graduated from Harvard in 1908, sharing a family tradition with, among others, several Samuel Eliots, Presi- dent Charles W. Eliot, Charles Eliot Norton, and Eking E. Morison. During his junior year he decided on teaching and writing history as an objective after graduation and in his twenty-fifth Harvard class report, he wrote: 'History is a hu- mane discipline that sharpens the intellect and broadens the mind, offers contacts with people, nations, and civilizations. -

Suicide Facts Oladeinde Is a Staff Writerall for Hands Suicide Is on the Rise Nationwide

A L p AN Stephen Murphy (left),of Boston, AMSAN Kevin Sitterson (center), of Roper, N.C., and AN Rick Martell,of Bronx, N.Y., await the launch of an F-14 Tomcat on the flight deckof USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71). e 4 24 e 6 e e Hidden secrets Operation Deliberate Force e e The holidays are a time for giving. USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) e e proves what it is made of during one of e e Make time for your shipmates- it e e could be the gift of life. the biggest military operations in Europe e e since World War 11. e e e e 6 e e 28 e e Grab those Gifts e e Merchants say thanks to those in This duty’s notso tough e e uniform. Your ID card is worth more Nine-section duty is off to a great start e e e e than you may think. and gets rave reviews aboardUSS e e Anchorage (LSD 36). e e PAGE 17 e e 10 e e The right combination 30 e e e e Norfolk hospital corpsman does studio Sailors care,do their fair share e e time at night. Seabees from CBU420 build a Habitat e e e e for Humanity house in Jacksonville, Fla. e e 12 e e e e Rhyme tyme 36 e e Nautical rhymes bring the past to Smart ideas start here e e e e everyday life. See how many you Sailors learn the ropes and get off to a e e remember. -

Jefferson's Failed Anti-Slavery Priviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism

MERKEL_FINAL 4/3/2008 9:41:47 AM Jefferson’s Failed Anti-Slavery Proviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism William G. Merkel∗ ABSTRACT Despite his severe racism and inextricable personal commit- ments to slavery, Thomas Jefferson made profoundly significant con- tributions to the rise of anti-slavery constitutionalism. This Article examines the narrowly defeated anti-slavery plank in the Territorial Governance Act drafted by Jefferson and ratified by Congress in 1784. The provision would have prohibited slavery in all new states carved out of the western territories ceded to the national government estab- lished under the Articles of Confederation. The Act set out the prin- ciple that new states would be admitted to the Union on equal terms with existing members, and provided the blueprint for the Republi- can Guarantee Clause and prohibitions against titles of nobility in the United States Constitution of 1788. The defeated anti-slavery plank inspired the anti-slavery proviso successfully passed into law with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Unlike that Ordinance’s famous anti- slavery clause, Jefferson’s defeated provision would have applied south as well as north of the Ohio River. ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Washburn University; D. Phil., University of Ox- ford, (History); J.D., Columbia University. Thanks to Sarah Barringer Gordon, Thomas Grey, and Larry Kramer for insightful comment and critique at the Yale/Stanford Junior Faculty Forum in June 2006. The paper benefited greatly from probing questions by members of the University of Kansas and Washburn Law facul- ties at faculty lunches. Colin Bonwick, Richard Carwardine, Michael Dorf, Daniel W. -

Themes in Modern American History Tutorial Schedule

HI2016 Themes in Modern American History Michaelmas Term, 2010 Tutorial Schedule Tutorial Assignments: Each student will be asked to make one presentation during the term. The student should choose a secondary source related to the week’s topic from a list of possibilities designated “recommended reading” (see below). He or she will offer a brief (3-5 minute) presentation on the text that illuminates the text’s main arguments and contributions to historical scholarship. No presentations will be held on week one of tutorials, but students will be expected to sign up during class for their future presentation. Readings: Please note that most required readings are available online; please use the links provided to ensure that you have the correct version of the document. All other required readings will be available in a box placed outside the history department. These photocopies are only to be borrowed and promptly returned (by the end of the day or the next morning if borrowed in the late afternoon). They are not to be kept. If students encounter trouble obtaining readings, they should email Dr. Geary at [email protected]. Week One: Puritans and Foundational American Myths (w/c 11 Oct.) Required Reading: John Winthrop, “A Model of Christian Charity” (available online at http://religiousfreedom.lib.virginia.edu/sacred/charity.html) Perry Miller, “Errand into the Wilderness,” William and Mary Quarterly, 10 (Jan., 1953), 3-32 (available online at www.jstor.org) Recommended Reading: James Axtell, Natives and Newcomers John Demos, Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the culture of early New England David D. Hall, Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgment: popular religious belief in early New England. -

The Evolution of U.S. Military Policy from the Constitution to the Present

C O R P O R A T I O N The Evolution of U.S. Military Policy from the Constitution to the Present Gian Gentile, Michael E. Linick, Michael Shurkin For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1759 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9786-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Since the earliest days of the Republic, American political and military leaders have debated and refined the national approach to providing an Army to win the nation’s independence and provide for its defense against all enemies, foreign and domestic.