Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

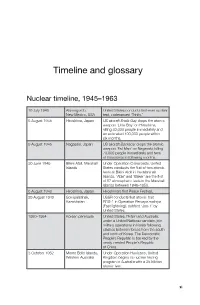

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

NUCLEAR POWER: MIRACLE OR MELTDOWN Jim Green

URANIUM MINING This PowerPoint is posted at www. tiny.cc /c1xwb URANIUM weighing benefits and problems BENEFITS Jobs Export revenue Climate change? PROBLEMS Environmental impacts ‘Radioactive racism’CLIMATE CHANGE? Nuclear weapons proliferation Nuclear power risks e.g. reactor accidents, attacks on nuclear plants JOBS 1750 = <0.02% of all jobs in Australia EXPORT REVENUE $751 million in 2009 -10 Uranium accounts for about one-third of one percent of Australian export revenue … 0.38% in 2007 0.36% in 2008/09 Approx. 0.25% in 2009/10 CLIMATE CHANGE BENEFITS OF URANIUM AND NUCLEAR POWER? Greenhouse emissions intensity (Grams CO2-e / kWh) Coal 1200 Nuclear 66 Wind 22 Does Australian uranium reduce global greenhouse emissions? The answer depends on whether Australian uranium displaces i) alternative uranium sources ii) more greenhouse-intensive energy sources (e.g. coal) iii) less greenhouse-intensive energy sources (e.g. wind power) CLIMATE CHANGE BENEFITS OF URANIUM AND NUCLEAR POWER? OLYMPIC DAM MINE Greenhouse emissions projected to increase to 5.9 million tonnes annually. This will make it impossible for South Australia to reach its legislated emissions target of 13 million tonnes annually by 2050. URANIUM weighing benefits and problems BENEFITS Jobs <0.02% Export revenue $ ~0.33% Climate change? benefits compared to fossil fuels but not renewables PROBLEMS Environmental impacts Nuclear weapons proliferation risks ‘Radioactive racism’ Nuclear power risks e.g. reactor accidents, attacks on nuclear plants Olympic Dam mine fire, 2001 Radioactive tailings, Olympic Dam Radioactive tailings, Olympic Dam Leaking tailings dam, Olympic Dam, 2008 BHP Billiton threatened “disciplinary action” against any workers caught taking photos of the mine site. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

The Threat of Nuclear Proliferation: Perception and Reality Jacques E

ROUNDTABLE: NONPROLIFERATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY The Threat of Nuclear Proliferation: Perception and Reality Jacques E. C. Hymans* uclear weapons proliferation is at the top of the news these days. Most recent reports have focused on the nuclear efforts of Iran and North N Korea, but they also typically warn that those two acute diplomatic headaches may merely be the harbingers of a much darker future. Indeed, foreign policy sages often claim that what worries them most is not the small arsenals that Tehran and Pyongyang could build for themselves, but rather the potential that their reckless behavior could catalyze a process of runaway nuclear proliferation, international disorder, and, ultimately, nuclear war. The United States is right to be vigilant against the threat of nuclear prolifer- ation. But such vigilance can all too easily lend itself to exaggeration and overreac- tion, as the invasion of Iraq painfully demonstrates. In this essay, I critique two intellectual assumptions that have contributed mightily to Washington’s puffed-up perceptions of the proliferation threat. I then spell out the policy impli- cations of a more appropriate analysis of that threat. The first standard assumption undergirding the anticipation of rampant pro- liferation is that states that abstain from nuclear weapons are resisting the dictates of their narrow self-interest—and that while this may be a laudable policy, it is also an unsustainable one. According to this line of thinking, sooner or later some external shock, such as an Iranian dash for the bomb, can be expected to jolt many states out of their nuclear self-restraint. -

Teacher's Guide

Winston Churchill Jeopardy Teacher Guide The following is a hard copy of the Jeopardy game you can download off our website. After most of the questions, you will find additional information. Please use this information as a starting point for discussion amongst your students. This is a great post- visit activity in order to see what your students learned while at the Museum. Most importantly, have fun with it! Museum Exhibits (Church, Wall, and Exhibit) $100 Q: From 1965 to 1967, this church was deconstructed into 7000 stones, shipped to Fulton, and rebuilt as a memorial to Winston Churchill’s visit. A: What is the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Aldermanbury - Please see additional information on the Church of St. Mary by going to our website and clicking on School Programs. $200 Q: In ‘The Gathering Storm’ exhibit, Churchill referred to this political leader as “…a maniac of ferocious genius of the most virulent hatred that has ever corroded the human breast…” A: Who is Adolf Hitler? $300 Q: In ‘The Sinews of Peace’ exhibit, what world leader influenced Churchill’s visit to Westminster College? A: Who is Harry S. Truman? $400 Q: These two items made regular appearances on Churchill’s desk. A: What are the cigar and whiskey? $500 Q: Churchill’s granddaughter, Edwina Sandys, created this sculpture as a representation and symbol of the end of the Cold War. It stands next to the Churchill Museum. A: What is “Breakthrough”? - This sculpture is made of eight sections of the Berlin Wall. Please see additional information on the Berlin Wall by going to our website and clicking on School Programs. -

The Fallacy of Nuclear Deterrence

THE FALLACY OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE LCol J.P.P. Ouellet JCSP 41 PCEMI 41 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs do not represent Department of National Defence or et ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used Ministère de la Défense nationale ou des Forces without written permission. canadiennes. Ce papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2015. le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2015. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 41 – PCEMI 41 2014 – 2015 EXERCISE SOLO FLIGHT – EXERCICE SOLO FLIGHT THE FALLACY OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE LCol J.P.P. Ouellet “This paper was written by a student “La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is a exigences du cours. L'étude est un scholastic document, and thus contains document qui se rapporte au cours et facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. It does not convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas necessarily reflect the policy or the nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion opinion of any agency, including the d'un organisme quelconque, y compris le Government of Canada and the gouvernement du Canada et le ministère Canadian Department of National de la Défense nationale du Canada. -

MARINEMARINE Life the ‘Taking Over the World’ Edition

MARINEMARINE Life The ‘taking over the world’ edition October/November 2012 ISSUE 21 Our Goal To educate, inform, have fun and share our enjoyment of the marine world with like- minded people. FeaturesFeatures andand CreaturesCreatures The Editorial Staff (and the zen bits, grasshopper) Emma Flukes, Co-Editor: Shallow understanding News from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. BREAKING: Super Trawler stopped – a summary of events & YOUR FEEDBACK 1 [I’m definitely not zen enough to understand any National & International Roundup 6 of this, but let’s run with it anyway...] State-by-state: QLD 8 Michael Jacques, Co-Editor: In the practice of WA 10 tolerance, one's enemy is the best teacher. NT 12 NT Honcho – Grant Treloar TAS 13 Tas Honchos - Phil White and Geoff Rollins SA Honcho – Peter Day WA Honcho – Mike Lee Bits & Pieces Federal marine parks cop a roasting 16 Climate change sceptics on the decline – are we finally getting through? 17 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication The imminent future of Wave Energy 18 are not necessarily the views of the editorial staff or Seaweed: the McDonald’s of the Ocean? 20 associates of this publication. We make no promise that any of this will make sense. Ugly animals need loving too! – an experiment in anthropomorphism 21 Feature Stories Cover Photo; Maori Octopus – John Smith Saving the sand of SA beaches (and more about those cuttlefish…) 24 We are now part of the wonderful The Montebello Islands (WA) - A nuclear wilderness 27 world of Facebook! Check us out, stalk our updates, and ‘like’ our Heritage and Coastal Features page to fuel our insatiable egos. -

Science, Technology and Medicine In

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1017/9781139044301.012 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Edgerton, D., & Pickstone, J. V. (2020). The United Kingdom. In H. R. Slotten, R. L. Numbers, & D. N. Livingstone (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Science: Modern Science in National, Transnational, and Global Context (Vol. 8, pp. 151-191). (Cambridge History of Science; Vol. 8). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139044301.012 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

PRG 1686 Series List Page 1 of 4 Sister Michele Madiga

_________________________________________________________________________ Sister Michele Madigan PRG 1686 Series List _________________________________________________________________________ Subject files relating to the campaign against the proposed radioactive 1 dump in South Australia. 1998-2004. 21.5 cm. Comprises subject files compiled by Michele Madigan: File 1: Environmentalists’ information and handouts File 2: Environmentalists’ information and handouts File 3: Greenpeace submission re radioactive wastes disposal File 4: Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta (Coober Pedy Senior Aboriginal Women’s Council) campaign against radioactive dump papers File 5: Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta – press clippings File 6: Coober Pedy town group campaign against a radioactive dump File 7: Postcards and printed material File 8: Michele Madigan’s personal correspondence against a radioactive dump File 9: SA Parliamentary proceedings against a radioactive dump File 10: Federal Government for a radioactive dump. File 11: Press cuttings. File 12: Brochures, blank petition forms and information, produced by various groups (Australian Conservation Foundation, Friends of the Earth, etc. Subject files relating to uranium mining (mainly in S.A.) 2 1996-2011. 10 cm. Comprises seven files which includes brochures, press clippings, emails, reports and newsletters. File 1 : Roxby Downs – Western Mining (WMC) / Olympic Dam File 2: Ardbunna elder, Kevin Buzzacott. File 3: Beverley and Honeymoon mines in South Australia. File 4: Background to uranium mining in Australia. File 5: Proposed expansion of Olympic Dam. File 6: Transportation of radioactive waste including across South Australia. File 7: Northern Territory traditional owners against Mukaty Dump proposal. PRG 1686 Series list Page 1 of 4 _________________________________________________________________________ Subject files relating to the British nuclear explosions at Maralinga 3 in the 1950s and 1960s. -

We Envy No Man on Earth Because We Fly. the Australian Fleet Air

We Envy No Man On Earth Because We Fly. The Australian Fleet Air Arm: A Comparative Operational Study. This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University 2016 Sharron Lee Spargo BA (Hons) Murdoch University I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………………………………………………….. Abstract This thesis examines a small component of the Australian Navy, the Fleet Air Arm. Naval aviators have been contributing to Australian military history since 1914 but they remain relatively unheard of in the wider community and in some instances, in Australian military circles. Aviation within the maritime environment was, and remains, a versatile weapon in any modern navy but the struggle to initiate an aviation branch within the Royal Australian Navy was a protracted one. Finally coming into existence in 1947, the Australian Fleet Air Arm operated from the largest of all naval vessels in the post battle ship era; aircraft carriers. HMAS Albatross, Sydney, Vengeance and Melbourne carried, operated and fully maintained various fixed-wing aircraft and the naval personnel needed for operational deployments until 1982. These deployments included contributions to national and multinational combat, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. With the Australian government’s decision not to replace the last of the aging aircraft carriers, HMAS Melbourne, in 1982, the survival of the Australian Fleet Air Arm, and its highly trained personnel, was in grave doubt. This was a major turning point for Australian Naval Aviation; these versatile flyers and the maintenance and technical crews who supported them retrained on rotary aircraft, or helicopters, and adapted to flight operations utilising small compact ships. -

Australian Radiation Laboratory R

AR.L-t*--*«. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. HOUSING & COMMUNITY SERVICES Public Health Impact of Fallout from British Nuclear Weapons Tests in Australia, 1952-1957 by Keith N. Wise and John R. Moroney Australian Radiation Laboratory r. t J: i AUSTRALIAN RADIATION LABORATORY i - PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF FALLOUT FROM BRITISH NUCLEAR WEAPONS TESTS IN AUSTRALIA, 1952-1957 by Keith N Wise and John R Moroney ARL/TR105 • LOWER PLENTY ROAD •1400 YALLAMBIE VIC 3085 MAY 1992 TELEPHONE: 433 2211 FAX (03) 432 1835 % FOREWORD This work was presented to the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia in 1985, but it was not otherwise reported. The impetus for now making it available to a wider audience came from the recent experience of one of us (KNW)* in surveying current research into modelling the transport of radionuclides in the environment; from this it became evident that the methods we used in 1985 remain the best available for such a problem. The present report is identical to the submission we made to the Royal Commission in 1985. Developments in the meantime do not call for change to the derivation of the radiation doses to the population from the nuclear tests, which is the substance of the report. However the recent upward revision of the risk coefficient for cancer mortality to 0.05 Sv"1 does require a change to the assessment we made of the doses in terms of detriment tc health. In 1985 we used a risk coefficient of 0.01, so that the estimates of cancer mortality given at pages iv & 60, and in Table 7.1, need to be multiplied by five.