Michael Rubin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Cluster Bulletin

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN April 2020 Fig.: Disinfection of an IDP camp as a preventive measure to ongoing COVID-19 Turkey Cross Border Pandemic Crisis (Source: UOSSM newsletter April 2020) Emergency type: complex emergency Reporting period: 01.04.2020 to30.04.2020 12 MILLION* 2.8 MILLION 3.7 MILLION 13**ATTACKS PEOPLE IN NEED OF HEALTH PIN IN SYRIAN REFUGGES AGAINST HEALTH CARE HEALTH ASSISTANCE NWS HNO 2020 IN TURKEY (**JAN - APR 2020) (A* figures are for the Whole of Syria HNO 2020 (All figures are for the Whole of Syria) HIGHLIGHTS • During April, 135,000 people who were displaced 129 HEALTH CLUSTER MEMBERS since December went back to areas in Idleb and 38 IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS REPORTING 1 western Aleppo governorates from which they MEDICINES DELIVERED TREATMENT COURSES FOR COMMON were displaced. This includes some 114,000 people 281,310 DISEASES who returned to their areas of origin and some FUNCTIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES HERAMS 21,000 IDPs who returned to their areas of origin, FUNCTIONING FIXED PRIMARY HEALTH forcing partners to re-establish health services in 141 CARE FACILITIES some cases with limited human resources. 59 FUNCTIONING HOSPITALS • World Health Day (7 April 2020) was the day to 72 MOBILE CLINICS celebrate the work of nurses and midwives and HEALTH SERVICES2 remind world leaders of the critical role they play 750,416 CONSULTATIONS in keeping the world healthy. Nurses and other DELIVERIES ASSISTED BY A SKILLED health workers are at the forefront of COVID-19 10,127 ATTENDANT response - providing high quality, respectful 8,530 REFERRALS treatment and care. Quite simply, without nurses, 822,930 MEDICAL PROCEDURES there would be no response. -

Health Cluster Bulletin, May 2018 Pdf, 1.17Mb

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN Gaziantep, May 2018 A man inspects a damaged hospital after air strikes in Eastern Ghouta. Source: SRD Turkey Cross Border Emergency type: complex emergency Reporting period: 01.05.2018 to 31.05.2018 11.3 MILLION 6.6 MILLION 3.58 MILLION 111 ATTACKS IN NEED OF INTERNALLY SYRIAN REFUGEES AGAINST HEALTH CARE HEALTH ASSISTANCE DISPLACED IN TURKEY (JAN-MAY 2018) (All figures are for the Whole of Syria) HIGHLIGHTS HEALTH CLUSTER Mentor Initiative treated 33,000 cases of 96 HEALTH PARTNERS & OBSERVERS Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and 52 cases of 1 Visceral Leishmaniasis in 2017 through 135 MEDICINES DELIVERED health facilities throughout Syria. TREATMENT COURSES FOR COMMON 369,170 DISEASES The Health Cluster’s main finds from multi- FUNCTIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES sectoral Rapid Needs Assessment which FUNCTIONING FIXED PRIMARY covered 180 communities (out of 220) from 166 HEALTH CARE FACILITIES seven sub-districts in Afrin from 3 to 8 May indicates limited availability of health facilities 82 FUNCTIONING HOSPITALS and medical staff, lack of transportation and 70 MOBILE CLINICS the lack of medicines and specialized services. HEALTH SERVICES The medical referral mechanism implemented 1 M CONSULTATIONS in Idleb governorate includes 48 facilities and 10,210 DELIVERIES ASSISTED BY A SKILLED 14 NGO partners that will be fully operational ATTENDANT as a network by end of August. The network, 8,342 REFERRALS which also includes 9 secondary health care VACCINATION facilities, in total serves a catchment 2 population of 920,000 people. In May 2018, 29,646 CHILDREN AGED ˂5 VACCINATED these facilities produced 1,469 referrals. DISEASE SURVEILLANCE In northern Syria as of end of May, there are 495 SENTINEL SITES REPORTING OUT OF 77 health facilities that are providing MHPSS A TOTAL OF 500 services, including the active mhGAP doctors FUNDING $US3 who are providing mental health 63 RECEIVED 14.3% 85.7% GAP consultations. -

The Turkish War on Afrin Jeopardizes Progress Made Since the Liberation of Raqqa April 2018

Viewpoints No. 125 The Turkish War on Afrin Jeopardizes Progress Made Since the Liberation of Raqqa April 2018 Amy Austin Holmes Middle East Fellow Wilson Center Turkey’s assault on Afrin represents a three-fold threat to the civilian population, the model of local self-governance, and the campaign to defeat the Islamic State. None of this is in the interest of the United States. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ The Turkish operation in Afrin is not just another battle in a small corner of Syria, but represents a new stage in the Syrian civil war and anti-ISIS campaign. President Erdoğan’s two-month battle to capture Afrin signals that Turkey will no longer act through proxies, but is willing to intervene directly on Syrian territory to crush the Kurdish YPG forces and the experiment in self-rule they are defending.i Emboldened after claiming victory in Afrin, and enabled by Russia, Erdoğan is threatening further incursions into Syria and Iraq. Erdoğan has demanded that American troops withdraw from Manbij, so that he can attack the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) who are stationed in the area, and who have been our most reliable partners in the anti-ISIS coalition. If Erdoğan is not deterred, much of the progress made since the liberation of Raqqa could be in jeopardy. The Afrin intervention has already displaced at least 150,000 people. Many of them are Kurds, Yezidis, or Christians who established local government councils in the absence of the regime over the past five years. Even if imperfect, the self-administration is an embryonic form of democracy that includes women and minorities while promoting religious tolerance and linguistic diversity. -

Syrie : Situation De La Population Yézidie Dans La Région D'afrin

Syrie : situation de la population yézidie dans la région d’Afrin Recherche rapide de l’analyse-pays Berne, le 9 mai 2018 Impressum Editeur Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés OSAR Case postale, 3001 Berne Tél. 031 370 75 75 Fax 031 370 75 00 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.osar.ch CCP dons: 10-10000-5 Versions Allemand et français COPYRIGHT © 2018 Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés OSAR, Berne Copies et impressions autorisées sous réserve de la mention de la source. 1 Introduction Le présent document a été rédigé par l’analyse-pays de l’Organisation suisse d’aide aux ré- fugiés (OSAR) à la suite d’une demande qui lui a été adressée. Il se penche sur la question suivante : 1. Quelle est la situation actuelle des Yézidi-e-s dans la région d’Afrin ? Pour répondre à cette question, l’analyse-pays de l’OSAR s’est fondée sur des sources ac- cessibles publiquement et disponibles dans les délais impartis (recherche rapide) ainsi que sur des renseignements d’expert-e-s. 2 Situation de la population yézidie dans la région d’Afrin De 20’000 à 30’000 Yézidi-e-s dans la région d'Afrin. Selon un rapport encore à paraître de la Société pour les peuples menacés (SPM, 2018), quelque 20 000 à 30 000 Yézidis vivent dans la région d'Afrin. Depuis mars 2018, Afrin placée sous le contrôle de la Turquie et des groupes armés alliés à la Turquie. Le 20 janvier 2018, la Turquie a lancé une offensive militaire pour prendre le contrôle du district d'Afrin dans la province d'Alep. -

Operation Euphrates Shield: Implementation and Lessons Learned Lessons and Implementation Shield: Euphrates Operation

REPORT REPORT OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD: IMPLEMENTATION OPERATION AND LESSONS LEARNED EUPHRATES MURAT YEŞILTAŞ, MERVE SEREN, NECDET ÖZÇELIK The report presents a one-year assessment of the Operation Eu- SHIELD phrates Shield (OES) launched on August 24, 2016 and concluded on March 31, 2017 and examines Turkey’s future road map against the backdrop of the developments in Syria. IMPLEMENTATION AND In the first section, the report analyzes the security environment that paved the way for OES. In the second section, it scrutinizes the mili- tary and tactical dimensions and the course of the operation, while LESSONS LEARNED in the third section, it concentrates on Turkey’s efforts to establish stability in the territories cleansed of DAESH during and after OES. In the fourth section, the report investigates military and political MURAT YEŞILTAŞ, MERVE SEREN, NECDET ÖZÇELIK lessons that can be learned from OES, while in the fifth section, it draws attention to challenges to Turkey’s strategic preferences and alternatives - particularly in the north of Syria - by concentrating on the course of events after OES. OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD: IMPLEMENTATION AND LESSONS LEARNED LESSONS AND IMPLEMENTATION SHIELD: EUPHRATES OPERATION ANKARA • ISTANBUL • WASHINGTON D.C. • KAHIRE OPERATION EUPHRATES SHIELD IMPLEMENTATION AND LESSONS LEARNED COPYRIGHT © 2017 by SETA All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, without permission in writing from the publishers. SETA Publications 97 ISBN: 978-975-2459-39-7 Layout: Erkan Söğüt Print: Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık A.Ş., İstanbul SETA | FOUNDATION FOR POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RESEARCH Nenehatun Caddesi No: 66 GOP Çankaya 06700 Ankara TURKEY Tel: +90 312.551 21 00 | Fax :+90 312.551 21 90 www.setav.org | [email protected] | @setavakfi SETA | İstanbul Defterdar Mh. -

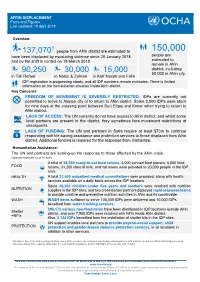

People from Afrin District Are Estimated to Have Been Displaced by Escalating Violence Since 20 January 2018 and by the Shift In

AFRIN DISPLACEMENT Facts and Figures Last updated: 18 April 2018 Overview: 1 137,070 people from Afrin district are estimated to 150,000 have been displaced by escalating violence since 20 January 2018 people are and by the shift in control on 18 March 2018 estimated to remain in Afrin 90,250 30,000 15,000 district, including 50,000 in Afrin city. in Tall Refaat in Nabul & Zahraa in Kafr Naseh and Fafin IDP registration is progressing slowly, and all IDP numbers remain estimates. There is limited information on the humanitarian situation inside Afrin district. Key Concerns: FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT IS SEVERELY RESTRICTED. IDPs are currently not permitted to move to Aleppo city or to return to Afrin district. Some 2,000 IDPs were stuck for nine days at the crossing point between Burj Elqas and Kimar when trying to return to Afrin district. LACK OF ACCESS: The UN currently do not have access to Afrin district, and whilst some local partners are present in the district, they sometimes face movement restrictions at checkpoints. LACK OF FUNDING: The UN and partners in Syria require at least $73m to continue responding with life-saving assistance and protection services to those displaced from Afrin district. Additional funding is required for the response from Gaziantep. Humanitarian Assistance: The UN and partners are scaling-up the response to those affected by the Afrin crisis. [selected highlights as of 16 April] A total of 28,350 ready-to-eat food rations, 3,000 canned food parcels, 5,000 food FOOD rations, 31,200 litres of milk, and hot meals were provided to 20,000 people in the IDP sites. -

Whole-Of-Syria DONOR UPDATE: January-June 2019 5 1

Whole-of-Syria DONOR UPDATE January - June 2019 A WHO staff member greets a mother and her child outside the Paediatric Hospital in Damascus. Credit: WHO CONTENT 04 FOREWORD 06 1. OVERVIEW 10 2. GEOGRAPHICAL AREAS OF FOCUS 10 North-west Syria 13 North-east Syria 18 Al-Hol camp 20 South-west Syria 21 Rukban settlement 22 3. SHIFTING TO A HEALTH RESPONSE BASED ON THE SEVERITY SCALE 25 4. ATTACKS ON HEALTH CARE 25 Background 25 Attacks on health care from a global perspective 26 Attacks in Syria in 2019 28 The consequences of attacks on health care 29 Impact of attacks on health care delivery in Syria 32 5. ACTIVITIES JANUARY-JUNE 2019 32 Trauma care 33 Secondary health care and referral 35 Primary health care 38 Immunization and polio eradication 38 Mental health and psychosocial support WHO Country Office (Damascus – Syrian Arab Republic) 40 Health information Dr Ni’ma Abid, WHO Representative a.i 41 Health sector coordination [email protected] 42 Nutrition 43 Water, sanitation and hygiene 43 Working with partners WHO Country Office (Damascus – Syrian Arab Republic) Noha Alarabi, Donor Relations 6. MAIN DISEASES OF CONCERN [email protected] 45 45 Measles WHO Headquarters (Geneva, Switzerland) 46 Polio Laila Milad, Manager, Resource Mobilization 47 Cutaneous leishmaniasis [email protected] 47 Tuberculosis 49 7. WHOLE-OF-SYRIA INTERNAL COORDINATION © World Health Organization 2019 8. FUNDS RECEIVED AS OF END JUNE 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution- 49 NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons. -

2019 Gsm Draft Report

MEDITERRANEAN AND MIDDLE EAST SPECIAL GROUP (GSM) THE SITUATION IN SYRIA: AN UPDATE Draft Report by Ahmet Berat ÇONKAR (Turkey) Rapporteur 040 GSM 19 E rev. 1 | Original: English | 4 April 2019 Until this document has been adopted by the Mediterranean and Middle East Special Group, it only represents the views of the Rapporteur. 040 GSM 19 E TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: A SIGNIFICANTLY ALTERED BATTLEFIELD .......................... 1 II. THE CURRENT DIPLOMATIC CRISIS OVER SYRIA ............................................ 4 III. RUSSIA’S APPROACH TO SYRIA ......................................................................... 6 IV. IRAN’S ROLE AND AMBITIONS IN SYRIA ............................................................ 8 V. THE VIEW FROM ANKARA .................................................................................... 9 VI. THE VIEW FROM ISRAEL .................................................................................... 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY .................................................................................................... 14 040 GSM 19 E I. INTRODUCTION: A SIGNIFICANTLY ALTERED BATTLEFIELD 1. The tragic and bloody civil war in Syria has, since its inception, exposed many of the fundamental fault lines dividing that region and threatening its stability. Those fault lines, moreover, have global implications as well, and, in some respects, mirror rivalries that are shaping contemporary international politics. Precisely for that reason, it would not be accurate to characterise this conflict simply as a civil war. Rather, it has become something of a “great game” in which both regional and external powers as well as non-state actors hold high stakes and conflicting interests. 2. But it is a great game that has also had terrible humanitarian consequences which have spilt into the neighbouring countries, broader region and beyond to Europe. A horrific refugee crisis that has compelled millions to flee their homes is the most obvious expression of the transnational humanitarian consequences of this war. -

Afrin Sitrep #1

Syrian Arab Republic : Afrin Crisis Situation Report No. 1 as of 5 April 2018 This report is produced by OCHA in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 29 March to 5 April 2018. Highlights 137 ,070 20 ,000 32,200+ $73m people remain outpatient medical Nutrition supplies in additional funding displaced from Afrin district consultations conducted on delivered for children under required by the UN and to other locations in Aleppo partners in Syria to assist a daily basis five and mothers governorate those affected • Following military confrontations in the Afrin district of Aleppo governorate since 20 January an estimated 137,070 people remain displaced in the Tall Refaat area, Nabul and Zahraa, Fafin, and surrounding villages. • There is a lack of freedom of movement for IDPs, and many continue to be prevented by different parties to the conflict from seeking safety and services in Aleppo city or from returning to their homes in Afrin district. • The UN and its partners have scaled up the response to the displaced in the Tall Refaat area, Nabul and Zahraa, Fafin, and surrounding villages, with the provision of food, NFIs, WASH, shelter, nutrition and health and protection services among others forms of assistance. Between 02 and 04 April, several UN shipments consisting of food supplies, as well as NFIs, health and WASH items were sent to assist the affected population that remains in Afrin district. Distribution of these supplies by Syrian NGOs on the ground is ongoing. • The UN and partners in Damascus reiterate that they are facing a $73m funding gap to respond with life-saving assistance and protection services to all those displaced from Afrin district to Tall Refaat and surrounding communities and are urgently appealing for additional funding. -

Syria: Recent Developments in North- Western Syria (Idleb Governorate and Afrin District) (As of 23 January 2018) Highlights

Turkey | Syria: Recent Developments in North- western Syria (Idleb Governorate and Afrin District) (as of 23 January 2018) Highlights • Hostilities in southern and south-eastern rural Idleb and southern rural Aleppo continued throughout the period between 16 and 22 January. • Civilian displacement in Idleb Governorate continues as hostilities intensify. The Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster tracked a total of 247,765 displacements to central and northern rural Idleb, as well as northern rural Hama (some may be secondary displacements), between 15 December and 22 January. • On 20 January, Turkish officials announced the start of Operation Olive Branch in Afrin District. Following the announcement, hostilities intensified significantly in Afrin District, resulting in displacement and casualties. • The ongoing hostilities in Idleb Governorate and the recent escalation in violence in Afrin District raise concerns regarding the protection of civilians, especially considering the concentration of civilians in both of these locations. • Concerns are raised about the restrictions on the freedom of movement of civilians in Afrin District which were imposed by the Afrin local authorities. Reports indicate that local authorities closed exit points from Afrin District, making it impossible for civilians to seek refuge in the nearby communities. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Coordination Saves Lives | www.unocha.org | https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/stima Turkey | Syria: Recent Developments in North-western Syria | 2 Situation Overview Between 16 and 22 January, hostilities between Government of Syria (GoS) forces and non-state armed groups (NSAGs) continued in southern and south-eastern rural Idleb, as well as southern rural Aleppo. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-IZ-100-17-CA021 March 2018 Monthly Report Appendices — March 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, William Raynolds, Allison Cuneo, Darren Ashby, Gwendolyn Kristy, Nour Halabi, Kyra Kaercher Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 12 Incident Reports: Iraq 88 Incident Reports: Libya 115 Satellite Imagery and Geospatial Analysis 137 Heritage Timeline 141 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points Syria ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Batuta, one of the "Dead Cities" of Northern Syria, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Aleppo Governorate was completely dismantled. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 16-0160 UPDATE ○ Artifacts in the Ain Dara Museum in Ain Dara, Aleppo Governorate have been left unguarded and exposed to the elements. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0067 ○ Alleged Turkish shelling damaged the Shrine of Yagmur Dada in Mabatli, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0068 ○ Suspected Syrian Liberation Front shelling reportedly damaged al-Adnan Mosque in Urm al-Kubra, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0069 ○ Suspected Free Syrian Army fighters reportedly vandalized a Yezidi shrine, Shrine of Kara Jorna in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0071 ○ Reported FSA and Turkish fighters defaced the Statue of Rafiq al-Watani in Afrin, Aleppo Governorate. -

A/HRC/40/70 Advance Edited Version

A/HRC/40/70 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 31 January 2019 Original: English Human Rights Council Fortieth session 25 February–22 March 2019 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic*, ** Summary Extensive military gains made by pro-government forces throughout the first half of 2018, coupled with an agreement between Turkey and the Russian Federation to establish a demilitarized zone in the north-west, led to a significant decrease in armed conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic in the period from mid July 2018 to mid January 2019. Hostilities elsewhere, however, remain ongoing. Attacks by pro-government forces in Idlib and western Aleppo Governorates, and those carried out by the Syrian Democratic Forces and the international coalition in Dayr al-Zawr Governorate, continue to cause scores of civilian casualties. In the aftermath of bombardments, civilians countrywide suffered the effects of a general absence of the rule of law. Numerous civilians were detained arbitrarily or abducted by members of armed groups and criminal gangs and held hostage for ransom in their strongholds in Idlib and northern Aleppo. Similarly, with the conclusion of Operation Olive Branch by Turkey in March 2018, arbitrary arrests and detentions became pervasive throughout Afrin District (Aleppo). In areas recently retaken by pro-government forces, including eastern Ghouta (Rif Dimashq) and Dar’a Governorate, cases of arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance were perpetrated with impunity. After years of living under siege, many civilians in areas recaptured by pro-government forces also faced numerous administrative and legal obstacles to access key services.