Ethnographic Explorations of Trust and Indian Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from the Depositories

UK BRISTOL Dynamatic-Oldland Aerospace™, Dynamatic Limited, UK SWINDON Dynamatic® Hydraulics, Dynamatic Limited, UK GERMANY DYNAMATIC ERLA Eisenwerk Erla GmbH T SI NGAPORE ECHNOLOGIES JKM Global PTE Limited INDIA CHENNAI L Dynametal®, Dynamatic Technologies Ltd. IMITE JKM Automotive™, Dynamatic Technologies Ltd. JKM Ferrotech Limited COIMBATORE D ANNUAL REPORT 2012-13 REPORT ANNUAL JKM Wind Farm, Dynamatic Technologies Ltd BANGALORE Dynamatic® Hydraulics, Dynamatic Technologies Ltd. Dynamatic homeland security™, Dynamatic Technologies Ltd. Dynamatic-Oldland Aerospace™, Dynamatic Technologies Ltd. Powermetric® Design, Dynamatic Technologies Ltd. JKM Research Farm Limited NASIK Dynamatic-Oldland Aerospace™, Dynamatic Technologies Ltd. Dynamatic Technologies Limited Dynamatic Limited, UK Eisenwerk Erla GmbH, Germany JKM Ferrotech Limited AS 9100 C: 2009-01 EMS 571485 AS 9100, Rev C EN 9100: 2009 FM 571484 JIS Q9100: 2009 www.dynamatics.com 20000856 ASH09 & 20006127 www.dynamatics.com www.jkm-erla.com DYNAMATIC T ECHNOLOGIES L IMITED Dynamatic Park Peenya Bangalore 560 058 India Tel +91 80 2839 4933 / 34 / 35 Fax +91 80 2839 5823 ©2013 Dynamatic Technologies Limited. All rights reserved. The logo, Dynamatic®, Dynamatic Technologies and the trademarks – Dynamatic® Hydraulics, Dynamatic Homeland SecurityTM, Dynamatic-Oldland Aerospace™, Dynametal®, Powermetric® Design, JKM AutomotiveTM, JKM FerrotechTM , JKM Global, JKM Wind Farm, Eisenwerk Erla, JKM Erla AutomotiveTM - and its logos are the exclusive property of Dynamatic Technologies Limited and may not be used without express prior written permission. Content, graphics and photographs in this Report are the property of Dynamatic Technologies Limited and may not be used without permission. “Adversity is the mother of progress.” - Mahatma Gandhi Dear Fellow Shareholder, 1700 On behalf of the Board of Directors 1650 of Dynamatic Technologies Limited 1600 and its Subsidiaries, I take pleasure in 1550 presenting you with Audited Financial 1500 Statements for the year 2012-13. -

Annual Report 2020-21 Is Being Sent Only Through Electronic Mode to Those Members Whose Email Addresses Are Registered with the Company/Registrars/Depositories

T. STANES AND COMPANY LIMITED CIN : U02421TZ1910PLC000221 Board of Directors Mr. A. Krishnamoorthy, (Chairman) Mr. S. Ramanujachari, (Director) Mr. K.S. Hegde, (Director) (Upto 16th October, 2020) Mrs. Lakshmi Narayanan, (Whole-time Director) Mr. P.M. Venkatasubramanian, (Independent Director) Mr. R. Vijayaraghavan, (Independent Director) Mr. K.K. Unni, (Independent Director) Mr. N.P. Mani, (Independent Director) Company Secretary Mr. G. Ramakrishnan (Upto 31st December, 2020) Auditors M/s. Fraser & Ross Chartered Accountants, Coimbatore. CONTENTS Page No. Bankers Central Bank of India Notice of Annual General Meeting 3 Directors' Report and Annexures 19 Registrar & Share Transfer Agent Auditors' Report 32 M/s.Integrated Registry Management Services Pvt. Ltd., Balance Sheet 40 Second Floor, Kences Towers, No.1-Ramakrishna Street, North Usman Road, T. Nagar, Statement of Profit and Loss 41 Chennai - 600 017. Changes in Equity 42 Cash Flow Statement 43 Registered Office Notes to Financial Statements 45 8/23-24, Race Course Road, Coimbatore - 641 018. Phone - 0422-2221514, 2223515-17 Form AOC 1 84 Email : [email protected] Consolidated Financial Statements 85 Website : www.tstanes.com T. STANES AND COMPANY LIMITED CIN: U02421TZ1910PLC000221 Email id: [email protected] Website: www.tstanes.com Registered Office: 8/23-24, Race Course Road, Coimbatore - 641 018. NOTICE is hereby given that the 111th Annual General Meeting of the Company will be held on Friday, the 06th August, 2021 at 12.15 P.M. through Video Conference (VC) or Other Audio -

White Paper – Automotive Industry

White Paper – Automotive Industry Technology Cluster Manager (TCM) Technology Centre System Program (TCSP) Office of DC MSME, Ministry of MSME October, 2020 TCSP: Technology Cluster Manager White Paper: Automotive Industry Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.2 OBJECTIVE OF WHITE PAPER ................................................................................................................................ 7 2 SECTOR OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 GLOBAL SCENARIO ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Structure of Automotive Industry ............................................................................................................ 9 Global Business Trends .......................................................................................................................... 10 Product and Demand ............................................................................................................................. 12 Production and Supply Chain ................................................................................................................ -

Oracle E-Business Suite Release 12 and 12.1 Reference Booklet, March

Oracle E-Business Suite Release 12 and 12.1 Customer Success Stories INFORMATION FOR SUCCESS March 2013 Table of Contents Index Page Introduction Letter: Cliff Godwin, Senior Vice President, Applications Development iii Customers Listed Alpha Matrix Oracle E-Business Suite Release 12.1 v Customers Listed Alpha Matrix Oracle E-Business Suite Release 12 xi Customers Listed by Industry xix Oracle E-Business Suite Release 12.1 Customer Stories 1 Oracle E-Business Suite Release 12 Customer Stories 241 Introduction Letter This reference booklet contains several hundred success stories summarizing how Oracle E-Business Suite customers, who have implemented or upgraded to the latest release, have achieved real business results. These customer stories represent the broad use and continued growth of Oracle’s E-Business Suite applications, from around the world, in a variety of industries, enabling businesses to think globally to make better decisions, work globally to be more competitive, and manage globally to lower costs and increase performance. With a new user experience and hundreds of cross-industry capabilities spanning enterprise resource planning, customer relationship management, and supply chain planning, our most current release helps customers manage the complexities of global business environments no matter if the organization is small, medium or large in size. As part of Oracle’s Applications Unlimited strategy, Oracle’s E-Business Suite applications will continue to be enhanced, thus protecting and extending the value of your software investment. We hope you find this representative sample of customer success stories a valuable resource. We will be updating this book on a regular basis so stay tuned. -

NET ZERO ISSUE See Feature on Page 19

The quarterly magazine for The Association of Manufacturers and suppliers of Power Systems and ancillary equipment 2021 Summer AMPS Power THE NET ZERO ISSUE See feature on page 19 in this issue... TC Blog – How does AMPS Busting the Ireland Golf Day Jargon Solve its Page 24 Page 6 Data Centre Challenge? Page 23 Welcome WESTMINSTER VIEW By Charles Chetwynd-Talbot, the Rt. Hon. Earl of Shrewsbury & Talbot DL. Here at Westminster, Her Majesty opened the new Session of The second point I raised was that there are many SME’s in outlying Parliament but without the usual pomp and ceremony, due to areas such as Welshpool, Wrexham, Shrewsbury and the like all over COVID-19 restrictions. Her presence in person following the the UK, which in the past have missed out on funding and support for recent funeral of her husband Prince Philip, showed all of us just Skills Training, with the bulk of government assistance being targeted what a truly remarkable and dutiful person she is. into the industrial conurbations. I believe that all cases should be judged The Queen’s Speech, which states the Government’s intended on their merits and be awarded proper funding according to their legislative programme for the forthcoming Session, was packed with individual requirements. This Bill is so important for the future more than 30 Bills. Some, like the Environment Bill, have been carried of manufacturing industry in this Country. forward from the previous Session. That particular Bill is complex, wide We now move to the next stage during the coming weeks. -

Thinking Across Disciplines

THINKING ACROSS DISCIPLINES - INTERDISCIPLINARITY IN RESEARCH AND EDUCATION DEA / FBE THINKING ACROSS DISCIPLINES - INTERDISCIPLINARITY IN RESEARCH AND EDUCATION AUGUST 2008 2 FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................... 2 OBJECTIVES AND RESULTS ............................................................................................................ 3 1. ON THE WAY TOWARD INTERDISCIPLINARITY .........................................................................15 1.1 Knowledge across borders creates value ...........................................................................15 1.2 Interdisciplinarity requires world-class research and education .........................................17 1.3 Increased need for interdisciplinarity .................................................................................18 1.4 Forces promoting interdisciplinarity ..................................................................................20 1.5 Time for action ..................................................................................................................21 2. WHAT IS INTERDISCIPLINARITY? .............................................................................................23 2.1 The need for a common understanding ..............................................................................23 2.2 What is interdisciplinary research and education? .............................................................23 -

State Industrial Profile Tamil Nadu

STATE INDUSTRIAL PROFILE 2014-15 TAMIL NADU by MSME - DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE MINISTRY OF MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (MSME) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 65/1, GST Road, Guindy, Chennai-600032 Tel: 044-22501011–12-13 Fax: 044-22501014 Website: www.msmedi-chennai.gov.in email: [email protected] FOREWORD MSME-Development Institute (MSME-DI), Chennai has brought out a compendium on ‘State Industrial Profile of Tamil Nadu-204-15’ a very useful reference material for the aspiring/existing entrepreneurs, Industrial Associations, research scholars on MSMEs etc. The compendium inter alia gives various data/details on MSMEs in the State of Tamil Nadu including fact sheet of Tamil Nadu, General Profile of the State, Economic Profile, performance of major industries sectors, district - wise investment opportunities, identified clusters, various incentives/schemes of Govt. Of India and Govt. Tamil Nadu for MSMEs , performance of major Banks on credit flow to MSE sector etc. The data/details covered in this compendium has been prepared based on the information available/furnished by the Office of Industries Commissioner and Director of Industries and Commerce Govt. Of Tamil Nadu and Govt. Web sites related to Industry. I wish to place on record my appreciation to the team work of Economic Investigation Division of this Institute for bringing out this useful guide. The performance of MSME-DI, Chennai has been improving every year and I wish to thank all our colleagues including Branch MSME-DIs, Field Offices of MSME, Office of Industries Commissioner and Director of Industries and Commerce, Govt. Of Tamil Nadu, District Industries Centres, Industries Associations, Financial Institutions, NGOs, aspiring/existing entrepreneurs and other stake holders for their continued support extend to this Institute for achieving our mission and vision of this Institute. -

Post Show Report

|1| Foreword IESS VII is the biggest platform for the Indian exporters to widen their client base and develop their businesses across the globe as the largest Trade and Investment Show in South India. The VIIth IESS witnessed 14 sessions, more than 95 speakers, over 500 delegates from 100 nations, more than 300 Exhibitors and 10,000 business visitors. Subcontracting Expo, EEPC Mitra- Humanoid, Arjun Mark II Tank were the new attractions this year. The three day show was inaugurated on March 8, 2018 by the Tamil Nadu Deputy Chief Minister Mr O Panneerselvam, and the Czech Republic‘s Minister for Industry and Trade, Mr. Tomas Huner, in the august presence of Thiru P. Benjamin, Hon’ble SME & Rural Industries Minister, Govt. of Tamil Nadu; Thiru M C Sampath, Hon’ble Minister for Industries, Govt. of Tamil Nadu and Ms Rita Teaotia, Commerce Secretary, Govt of India . A message from Mr Suresh Prabhu, Hon’ble Union Minister of Commerce and Industry was read out at the inauguration. Bhupinder Singh Bhalla, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Mr Rakesh Shah, Former Chairman and Chairman of the Committee on Publicity, Exhibition and Delegation, EEPC India and Mr Bhaskar Sarkar joined the fanfare inaugural process with the beating of percussions! The Support from Ministry of Commerce and Industry, MSME , DHI, Flanders (Belgium) as the Focus Region, Tamil Nadu as the Host State, UP and Haryana as the Partner States. West Bengal as the Focus State. ISB as the Knowledge Partner, DHL as the Logistics Partner made this edition very powerful! The country pavilions had a strong presence of Bangladesh, Korea, Taiwan, UAE and Uzbekistan, besides the Czech Republic and Belgium. -

Ashok Leyland Hikes Stake in Optare to 75.1 Per Cent

CONTENTS 14 24 62 Editorial.............................................................................................................................. 8 AUTO EXPO PREVIEW All set for 11th Auto Expo ................................................................................................ 10 BUS INDUSTRY Ashok Leyland presenting new, innovative products ....................................................... 14 Volvo launching new range of buses ............................................................................... 18 Feature-rich Tata Divo Coach, Tata Starbus Ultra launched ........................................... 24 Ashok Leyland hikes stake in Optare to 75.1 per cent .................................................... 30 VEHICLE INDUSTRY Mahindra Navistar Awards for transport heroes .............................................................. 34 Sturdy Scania tipper designed for rough terrain .............................................................. 54 Isuzu IS12T truck launched in Kerala ............................................................................. 56 Eicher’s all-round good performance .............................................................................. 58 FOCUS ON TRAILERS TRAILER 2011, a runaway success ................................................................................ 60 Truck of the Year Award for Mercedes-Benz New Actros ................................................ 62 Benz study on reduced fuel use, CO2 emissions of trucks ............................................ -

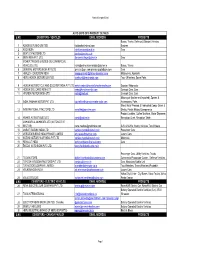

Products List

Auto Expo 2012 ‐ List of Exhibitors S.NO. COMPANY NAME PRODUCT ON DISPLAY CANADA PAVILION Assistance to Canadian companies in doing business with their Indian 1 HIGH COMMISSION OF CANADA counterpar 1) Overrunning Alternator Decoupler. 2) FEAD Tensioner 3) TorqFiltr® - Crankshaft Decoupler 4) SmartSprocket®. crankshaft torque cancellation sprocket. 5) Switchable Water Pump zulley 6) Timing Belt Tensioner 7) Idler Pulley 2 LITENS AUTOMOTIVE (INDIA) PRIVATE LIMITED 1) Lumbar Supports 2) Massage Units 3) Seat Suspensions 4) Wireless 3 LEGGETT & PLATT AUTOMOTIVE GROUP Charging 5) Mechanical Cables 1)Seat Cushioning 2) Seat Frames 3) Assembly Sequence Services 4) Interior 4 SHEELA WOODBRIDGE WRETHANES PVT LTD Trim Parts 5) NVH Components 6) Head Liner Substrates 5 CREAFORM INC 1) Handy Probe 2) Handy Scan 3) Metra Scan 4) Max Shot 5) CBD 6 BALLARD POWER SYSTEMS INC 1) Fuel Cell Stacks 2) Fuel Cell Modules 3) Fuel Cell Based Power Generators 7 CVTECH IBC INC 1) CVT : Continuously Variable Transmission 1) Plastic Muffler 2) Air Intake System 3) Air Boxes 4) Resonators 5) Engine 8 NOVO PLASTICS INC Covers 1) Automotive Chassis Front Lower Control Arm - Aluminum Forging 2) Automotive Chassis Rear suspension arm - Aluminum Stretch formed extrusions 3) Automotive Chassis Suspension links - Aluminum Stretch formed extrusions 4) Ball joints 5) Aluminum forgings 6) Aluminum Extruforms - 9 RAUFOSS AUTOMOTIVE COMPONENTS CANADA Stretch bending of extrusion profile 1) Alternator Tester 2) Starter Tester 3) Battery Pack Tester 4) E- Motor Tester 5) Electric Powertrain Tester 6) Solenoid Tester 7) Inverter Tester 8) Voltage 10 D&V ELECTRONICS LTD Regulator Tester 1) Roll Forming Equipment 2) Roll Forming Tooling 3) Cut-to-Length Equipment 4) Flatteners 5) Presses / Dies 6) Uncoilers / Coil Cars 7) Coil Packaging Equipment 8) Material Handling Equipment 9) Slitting Equipment 11 SAMCO MACHINERY LTD Software Solutions for the purpose of design feasibility, and costing of sheet 12 FORMING TECHNOLOGIE INCORPORTED metal components for the automotive parts manufacturing industry. -

IP Rings Ltd

SANSCO SERVICES - Annual Reports Library Services - www.sansco.net IP Rings Ltd. 17th Annual Report 2007 - 2008 www.reportjunction.com SANSCO SERVICES - Annual Reports Library Services - www.sansco.net f DIRECTORS A SIVASAILAM Esq. Chairman N VENKATARAMANI Esq. Vice Chairman K V SHETTY Esq. Managing Director YORISHIGE MAEDA Esq. Director R MAHADEVAN Esq. Director P M VENKATASUE3RAMANIAN Esq. Director R NATARAJAN Esq. Director N GOWRISHANKAR Esq. Whole Time Director S RANGARAJAN Esq. Associate Vice President (Finance) & Secretary AUDITORS Messrs. R.G.N. PRICE & COMPANY, CHENNAI LEGAL ADVISORS S RAMASUBRAMANIAM & ASSOCIATES, CHENNAI BANKERS STANDARD CHARTERED BANK CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA HDFC BANK LIMITED REGISTERED OFFICE FACTORY 'Arjay Apex Centre' D 11/12, Industrial Estate 24, College Road Maraimalai Nagar Chennai 600 006 Kancheepuram Dist. 603 209 Tel: (044) 4214 3593 / 4214 3594 Tel: (044) 2745 2816 / 4740 0597 / 4740 0598 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.reportjunction.com SANSCO SERVICES - Annual Reports Library Services - www.sansco.net CONTENTS Page Notice to Members 3 Directors' Report 9 Auditors' Certificate on Corporate Governance 14 Report on Corporate Governance 15 Management Discussion and Analysis Report 21 10 Years'Performance 23 Report of the Auditors to the Members 24 Accounts 27 Effective from May 1, 2008, the Company has appointed M/s. BTS Consultancy Services Pvt. Ltd. 'Panna Plaza', II Floor New No. 74, Old No. 134, Arcot Road Kodambakkam, Chennai - 600 024 Phone : 044 - 2372 3355, Fax : 044 - 2375 0282 E-mail: [email protected] as its Registrar & Share Transfer Agents www.reportjunction.com SANSCO3ERVICES - Annual Reports Library Services - www.sansco.het NOTICE TO THE MEMBERS NOTICE is hereby given that the SEVENTEENTH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING of the Members of IP Rings Ltd. -

Update Products List

MasterCompanyDetail AUTO EXPO 2010 PRODUCT DETAILS S.NO. EXHIBITORS - VEHCILES EMAIL ADDRESS PRODUCTS Buses, Trucks, Defence & Special Vehicles, 1 ASHOK LEYLAND LIMITED [email protected] Engines 2 AUDI INDIA [email protected] Cars 3 BENTLEY MOTORS LTD [email protected] 4 BMW INDIA PVT. LTD. [email protected] Cars EICHER TRUCKS & BUSES (VE COMMERCIAL 5 VEHICLES LTD) [email protected];[email protected] Buses, Trucks 6 GENERAL MOTORS INDIA PVT LTD [email protected];[email protected] Cars 7 HARLEY - DAVIDSON INDIA [email protected] Motocycles, Apparels 8 HERO HONDA MOTORS LIMITED [email protected] Two - Wheelers, Spare Parts 9 HONDA MOTORCYCLE AND SCOOTER INDIA PVT LTD [email protected] Scooter, Motorcycle 10 HONDA SIEL CARS INDIA LTD [email protected] Concept Cars, Cars 11 HYUNDAI MOTOR INDIA LTD [email protected] Concept Cars, Cars Motorcycle (Indian and Imported), Spares & 12 INDIA YAMAHA MOTOR PVT LTD [email protected] Accessories, Parts Sheet Metal Pressed & Fabricated Comp, Gears & 13 INTERNATIONAL TRACTORS LTD [email protected] Shafts, Plastic Molded Components Product Leaflets, Coffee Machine, Water Dispenser, 14 KRANTI AUTMOTIBLES LTD [email protected] Reception Chair, Reception Table MAHINDRA & MAHINDRA LTD (AUTOMOTIVE 15 SECTOR) [email protected] SUV & MUV's, Heavy Vehicles, Two Wheeler 16 MARUTI SUZUKI INDIA LTD [email protected] Passenger Cars 17 MERCEDES-BENZ INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED [email protected] Luxury Cars 18 SUZUKI MOTORCYLCE INDIA PVT LTD [email protected] Motorcyle 19 RENAULT INDIA [email protected] Cars 20 ŠKODA AUTO INDIA PVT.