Making Homes for the Arts in Sacred Places

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 Commongroundfall 2 0

14 COMMON GROUND FALL 2008 Save America’s TrPRESeERVING TaHE NATIOsN'S HEuRITAGE ONrE GRANeT AT A Ts IME BY MEGHAN HOGAN When Francis Scott Key spent the rainy night of September 13, 1814, watching the British bombardment of Fort McHenry—a pivotal battle in the War of 1812—he had only one question in his mind. Which flag would fly in the morning? The Union Jack or the Stars and Stripes? We all know the answer—he joyfully proceeded to write the Star-Spangled Banner, which became our national anthem. That same flag, hand-stitched by Mary Pickersgill in 1813, will soon be seen once again in a new display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. But in 1998, the flag wasn’t telling a story of patriotism, it was telling a story of age. It had lost eight feet of fabric, and despite careful treatment by Smithsonian curators, dirt and light were slowly destroying the weakened wool and cotton. Its own weight was a stress as it hung in the museum. In short, it was falling apart. So began a national campaign called Save America’s Treasures, with the flag one of the first and most recognized projects. Left: The first known photo of the flag that flew over Fort McHenry during the War of 1812—inspiring Francis Scott Key’s “Star-Spangled Banner”—taken in 1873 at the Boston Navy Yard. Conserved with help from a Save America’s Treasures grant, it will be unveiled this November in a room designed to “evoke Dawn’s early light.” Above left to right: Philadelphia’s historic Eastern State Penitentiary, the restored Majestic Showboat in Cincinnati, and Little Rock Central High School, the focus of the desegregation crisis in 1957, all grant recipients. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Status Report from Dutch AAT, Weda, 2017

Update Dutch AAT ITWG 2017 Content . Translation work . Management software Xtree . Concept proposals . Visual fashion and costume thesaurus . Events 6420 new concepts (2012-2016) Pref terms: 6420 Alternative terms: 1917 Use for terms: 535 Translation labels Translation N/A: 1598 literal translation: 749 Loanword: 143 Translation work Masaai (language) http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300388758 Vitales (genus): http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300389726 Tefon™: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300380055 Translation NA Abandoned dwellings/ verlaten woningen: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300386972 Singel sitter models/ portretten met één model http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300404138 suminagashi paper/ suminagashi-papier http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300387534 Literal translation Katana: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300386050 Buon Fresco http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300403944 abhaya mudra: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300386135 Loanwords Xtree thesaurus management Software What is xTree? • A central, web-based tool to administer vocabularies (e.g. thesauri, classifications, lists, taxonomies, folksonomies) • is semantically interoperable within ISO/DIS 25964-1 (ThesaurusConcept, ThesaurusArray, ConceptGroup), ANSI/NISO Z39.19-2005, ISO 2788 and DIN 1463-1 • is compatible with the data model of BS DD 8723-5 • has a multi-lingual data model • is usable with common web-browser software (e.g. Firefox 3, Internet Explorer 8) • is easy to handle (e.g. drag and drop) • uses the museumvok Webservice • uses SKOS RDF • is built for collaborative work http://xtree-public.digicult- • is developed with Open Source software verbund.de/vocnet/? • XSD- and RDF-based Webservice Xtree, managentsoftware New flag: ‘translation N/A’ Dutch AAT has a set of ‘Untranslatables’ How to flag these concepts? Checked but not translated… ‘half-tester beds’ ID 300038710 New flag: ‘literalN.B. -

JPEG Image Compression2.Pdf

JPEG image compression FAQ, part 2/2 2/18/05 5:03 PM Part1 - Part2 - MultiPage JPEG image compression FAQ, part 2/2 There are reader questions on this topic! Help others by sharing your knowledge Newsgroups: comp.graphics.misc, comp.infosystems.www.authoring.images From: [email protected] (Tom Lane) Subject: JPEG image compression FAQ, part 2/2 Message-ID: <[email protected]> Summary: System-specific hints and program recommendations for JPEG images Keywords: JPEG, image compression, FAQ, JPG, JFIF Reply-To: [email protected] Date: Mon, 29 Mar 1999 02:24:34 GMT Sender: [email protected] Archive-name: jpeg-faq/part2 Posting-Frequency: every 14 days Last-modified: 28 March 1999 This article answers Frequently Asked Questions about JPEG image compression. This is part 2, covering system-specific hints and program recommendations for a variety of computer systems. Part 1 covers general questions and answers about JPEG. As always, suggestions for improvement of this FAQ are welcome. New since version of 14 March 1999: * Added entries for PIE (Windows digicam utility) and Cameraid (Macintosh digicam utility). * New version of VuePrint (7.3). This article includes the following sections: General info: [1] What is covered in this FAQ? [2] How do I retrieve these programs? Programs and hints for specific systems: [3] X Windows [4] Unix (without X) [5] MS-DOS [6] Microsoft Windows [7] OS/2 [8] Macintosh [9] Amiga [10] Atari ST [11] Acorn Archimedes [12] NeXT [13] Tcl/Tk [14] Other systems Source code for JPEG: [15] Freely available source code for JPEG Miscellaneous: [16] Which programs support progressive JPEG? [17] Where are FAQ lists archived? This article and its companion are posted every 2 weeks. -

Installation Manual ESPAÑOL Instrucciones De Instalación FRANÇAIS Instructions D’Installation

SUNNY BOY 3.0-US / 3.8-US / 5.0-US / 6.0-US / 7.0-US / 7.7-US SB3.0-1SP-US-41 / SB3.8-1SP-US-41 / SB5.0-1SP-US-41 / SB6.0-1SP-US-41 / SB7.0-1SP-US-41 / SB7.7-1SP-US-41 SUNNY BO Y eManual ENGLISH Installation Manual ESPAÑOL Instrucciones de instalación FRANÇAIS Instructions d’installation SBxx-1SP-US-41-IA-xx-10 | 117821-00.01 | Version 1.0 Legal Provisions SMA Solar Technology AG ENGLISH Legal Provisions The information contained in these documents is the property of SMA Solar Technology AG. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, be it electronic, mechanical, photographic, magnetic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of SMA Solar Technology AG. Internal reproduction used solely for the purpose of product evaluation or other proper use is allowed and does not require prior approval. SMA Solar Technology AG makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, with respect to this documentation or any of the equipment and/or software it may describe, including (with no limitation) any implied warranties of utility, merchantability, or fitness for any particular purpose. All such representations or warranties are expressly disclaimed. Neither SMA Solar Technology AG nor its distributors or dealers shall be liable for any indirect, incidental, or consequential damages under any circumstances. The exclusion of implied warranties may not apply in all cases under some statutes, and thus the above exclusion may not apply. -

Honoring America's Fallen Heroes: An

HONORING AMERICA’S FALLEN HEROES: AN UPDATE ON OUR NATIONAL CEMETERIES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON DISABILITY ASSISTANCE AND MEMORIAL AFFAIRS OF THE COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION THURSDAY, MARCH 8, 2012 Serial No. 112–50 Printed for the use of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 73–294 WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 08:01 Apr 16, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 Y:\112CONG\DAMA\3-8-12\GPO\73294.TXT LEN VACREP180 with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS JEFF MILLER, Florida, Chairman CLIFF STEARNS, Florida BOB FILNER, California, Ranking DOUG LAMBORN, Colorado CORRINE BROWN, Florida GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida SILVESTRE REYES, Texas DAVID P. ROE, Tennessee MICHAEL H. MICHAUD, Maine MARLIN A. STUTZMAN, Indiana LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California BILL FLORES, Texas BRUCE L. BRALEY, Iowa BILL JOHNSON, Ohio JERRY McNERNEY, California JEFF DENHAM, California JOE DONNELLY, Indiana JON RUNYAN, New Jersey TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota DAN BENISHEK, Michigan JOHN BARROW, Georgia ANN MARIE BUERKLE, New York RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri TIM HUELSKAMP, Kansas MARK E. AMODEI, Nevada ROBERT L. TURNER, New York HELEN W. TOLAR, Staff Director and Chief Counsel SUBCOMMITTEE ON DISABILITY ASSISTANCE AND MEMORIAL AFFAIRS JON RUNYAN, New Jersey, Chairman DOUG LAMBORN, Colorado JERRY McNERNEY, California, Ranking ANN MARIE BUERKLE, New York JOHN BARROW, Georgia MARLIN A. -

2101-Washington-Ave-Nomination.Pdf

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC B UILDING , S TRUCTURE , S ITE , OR OBJECT P HILADELPHIA R EGISTER OF HISTORIC P LACES P HILADELPHIA HISTORICAL C OMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM ON CD (M S WORD FORMAT) 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:_____________2101____ _Washington_________ _Avenue______________________________________ Postal code:__19146-2532_____________ Councilmanic District:________2__________________ 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:______Howell______ &_ _Brothers_______ Wallpaper________ _Hangings_______ _Manufactory____________________________ Common Name:________Frankford_______ _Chocolate________ Company________ _Building________________________________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC R ESOURCE X Building Structure Site Object 4. P ROPERTY INFORMATION Condition: excellent good X fair poor ruins Occupancy: occupied X vacant under construction unknown Current use:__________Telecommunications_________________ and___ _Automobile_________ _Parking___________________________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See Page 1 6. DESCRIPTION See Page 2 7. S IGNIFICANCE See Page 13 Period of Significance (from year to year): from __1865_______ to __2012_______ Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_ _1865____, _1883______, 1912_______________________, 1964, 1967, 1968, 1975__________ 1865, 83: Unknown 1912: William C Haddock 1964: Uknown 1967, 68: Abraham Levy Architect, engineer, and/or designer:__1975:___ Unknown____________________________________________ -

Heritage Studies: an Odyssey in Learning

Heritage Studies: An Odyssey in Learning The Heritage Guide 2005-2006 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... 3 II. HERITAGE TEXTS ................................................................. 6 III. HERITAGE SEMINARS Heritage I .......................................................................... 7 Heritage II ......................................................................... 16 Heritage III: Asia............................................................... 29 Heritage III: Latin America............................................... 39 IV. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Reading ............................................................................. 46 Writing .............................................................................. 47 Cultural Literacy ............................................................... 49 Oral Communication ........................................................ 50 V. CLASS REQUIREMENTS AND EXPECTATIONS Attendance………………………..................................... 51 Registering for a Class; Add/Drop Procedures................. 51 How to Protect Your Work............................................... 51 Academic Honesty and Plagiarism.................................... 52 Penalties for Plagiarism..................................................... 53 How to Avoid Plagiarism.................................................. 53 VI. READING, WRITING, SPEAKING, AND LISTENING IN HERITAGE Reading ............................................................................ -

National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska Final Integrated Activity Plan/Environmental Impact Statement I Contents

National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska FINAL Integrated Activity Plan/ Environmental Impact Statement Volume 6 Appendices, Glossary, Bibliography Prepared by: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Anchorage, Alaska In cooperation with: North Slope Borough U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service November 2012 How the IAP/EIS is Organized VOLUME 1 Chapter 1 – Introduction: Summarizes the purpose of and need for this IAP/EIS and decisions to be made. Chapter 2 – Alternatives: Describes and compares proposed management alternatives. Chapter 3 – Affected Environment: Presents existing natural and socioeconomic resources in the NPR-A and trends, including those associated with climate change. VOLUME 2 Chapter 4 – Environmental Consequences (sections 4.1 – 4.4): Provides the assumptions upon which the impact analysis rests and evaluates impacts of Alternatives A and B-1 on resources and uses in the NPR-A relevant to making a decision among the alternatives. VOLUME 3 Chapter 4 – Environmental Consequences continued (sections 4.5 – 4.7): Evaluates impacts of Alternatives B-2 (preferred alternative), C, and D on resources and uses in the NPR-A relevant to making a decision among the alternatives. VOLUME 4 Chapter 4 – Environmental Consequences continued (sections 4.8 – 4.13): Evaluates the cumulative impacts on resources and uses in the NPR-A and other effects relevant to making a decision among the alternatives. VOLUME 5 Chapter 5 – Consultation and Coordination: Describes public and government (including tribal) consultation undertaken for this plan and the development of alternatives and lists the plan’s preparers. Chapter 6 – Comments and Responses: Presents public comments on the Draft IAP/EIS and responses to the comments. -

Artist Citations

Downtown Fremont Public Art Program (Temporary Installation) – Metamorphosis Downloaded by Alina Kwak Thursday, December 15th 2016, 2:27pm Call ID: 990676 Artist ID: 7754 Status: Received Helle scharlingtodd Contact Partner Contact via Email [email protected] Phone Cell Web Site glassandmosaics.com Mailing Address . Custom Answers 2) Statement Regarding ThemeArtist must provide a written statement (up to 150 words) as part of their submittal explaining how their sculpture addresses and illustrates the theme. Art is like music, it stimulates the mind and the senses. With this in mind I build my pieces with emphasis on space, form, color, line, rhythm, and content. Artists are image makers and like the world's antennas, they feel, think and express reality. Momentarily I focus on "defining our spaces", like building a new society, using color, form and line as the building blocks. In addition to my public art projects I have developed a series of "color molecule" sculptures. The sculptures represent an homage to the smallest building block of life, the molecules. The theme is called "metamorphosis" which means change, and I see my work fitiing to the theme, as we all have metamorphed from molecules to a human being, so honoring the smallest entity in us seems allright. The work has semi circular motions, which gives a light feeling. The piece is 14' x 6;' x 6'. It is powder coated, the main color being turquise with colored glass inserted in the molecules. When the light shines through 3) Art Installation and De-Installation PlanPlease reference the attached site plan and provide an installation and de-installation plan and requirements for the attachment of the Artwork and the type of hardware to be used for the attachment. -

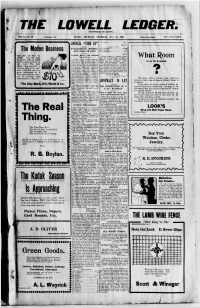

The Lowell Ledger. A

• i I ''f '' THE LOWELL LEDGER. INDEPENDENT- NOT NEUTRAL. VOL. XI, NO. 48 Circnlatloti 1106. liOWKU. MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, MAY 19, 1904 Official Newspaper. TKN PA(iK PAPKR 1. A. Wood 10 COUNCIL "TIED UP" $i:>i m IIKNKRAI. I TM). ON QUESTION OV APPROPUI- .1. n. Nicholson $2 11. w. Makes The Moden Business ATlNtJ $160 FOR .MACK. H. 15. Springett 4 ».') $7 45 President Hakes Cast Deciding man pays his bills by Motion made hy TniHteo Smith Veto In Favor. checks. Why not open that lilll of Hollon Mack for fl50 1h> What Room an account with us which .\( lite Conm-il inwtini? Monday allowed. Yeas: Collar, Nicholson. ninhl Hie inetnlwH (llvlilod on ilio Smith and the President. Nays: Is to be Papered can be subject to check at *im>Hlon of appropriatinu; fl.*»0 to Hicks, I/v and WineKar. Carried. any time? The bank jisHist Kolli'ii Mark In defraying tlie Trustee Ixv notified the President check when cancolled is cxponHCH of live Hiiil bvonjiht ap'ainKl that ho should not issue a warrant him by Knti .lolmson for Hie sliool- for payment of hill of Uollen Mack the best proof of the pay- iiK of iani fall. Trim toon. Nlcbolwon, for ¥15(1, as he as a taxpayer Intend- ment of any bill and is a Smith and Collar \'(i>tpd in favor of ed to secure an injunction restraining tin- rcKolniion andTnlstocK Winonar. payment of the same, as t here was great convenience as it I^cand lllrkH aufainHtlt. PiVHidi'iil no fund for such purpose. -

Aminet130mhaminet130mh 100% DIGITAL, HD, AVC, IPTV Set-Top Box with Security Housing

MODEL AmiNET130MHAmiNET130MH 100% DIGITAL, HD, AVC, IPTV Set-Top Box with Security Housing 100% Digital Supported Middlewares The AmiNET130MH is The First 100% Digital IPTV Set-Top Box Amino STB products are supported by leading IPTV middleware (STB), and builds upon Amino’s established reputation for providers for integration as part of a broadband TV solution. The innovation and leadership. A disruptive High Definition (HD) AmiNET130MH also supports development of applications in MPEG-4 IPTV STB with IP-only in and HDMI-only out, the HTML and Javascript. AmiNET130MH targets service operators whose primary proposition is HD. Advance Information: This document contains the specification for a product under continuous development. Specifications may High Definition (HD) change in any manner without notice The support of HD video at 720p and 1080i offers an exciting and dramatic viewing experience, with greater realism and detail Main Features especially in large display formats. Additionally, the HD graphics • MPEG-4 AVC/H.264 up to HP@L4, resolutions up to720p capabilities provide greater clarity and sharpness to support and 1080i enhanced user interface features such as more EPG data, • MPEG-2 up to MP@HL, resolutions up to 720p and 1080i banner advertising and information services. • HD Graphics (1280x720) • Digital HD output via HDMI with HDCP Return on Investment • Stereo Audio and Dolby 5.1 surround via Optical S/P-DIFand Removing the redundant analog A/V connections reduces the HDMI cost of the AmiNET130MH, thereby minimizing Service Provider • High performance integrated silicon architecture, 300 MIPs, capital expenditure and reducing the time to see a return on with dedicated codec support investment.