Vivaldi Takes Center Stage, Summer 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater FAIRWINDS GROWS MY MONEY SO I CAN GROW MY BUSINESS. Get the freedom to go further. Insured by NCUA. OPERA-2646-02/092719 Opera Orlando’s Carmen On the MainStage at Dr. Phillips Center | April 2021 Dear friends, Carmen is finally here! Although many plans have changed over the course of the past year, we have always had our sights set on Carmen, not just because of its incredible music and compelling story but more because of the unique setting and concept of this production in particular - 1960s Haiti. So why transport Carmen and her friends from 1820s Seville to 1960s Haiti? Well, it all just seemed to make sense, for Orando, that is. We have a vibrant and growing Haitian-American community in Central Florida, and Creole is actually the third most commonly spoken language in the state of Florida. Given that Creole derives from French, and given the African- Carribean influences already present in Carmen, setting Carmen in Haiti was a natural fit and a great way for us to celebrate Haitian culture and influence in our own community. We were excited to partner with the Greater Haitian American Chamber of Commerce for this production and connect with Haitian-American artists, choreographers, and academics. Since Carmen is a tale of survival against all odds, we wanted to find a particularly tumultuous time in Haiti’s history to make things extra difficult for our heroine, and setting the work in the 1960s under the despotic rule of Francois Duvalier (aka Papa Doc) certainly raised the stakes. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT SWR2 Musikstunde "Musikalisches Recycling - das ist doch noch gut?!" (1) Mit Nele Freudenberger Sendung: 22. Januar 2018 Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2017 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Musikstunde können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de SWR2 Musikstunde mit Nele Freudenberger 22. Januar – 26. Januar 2018 "Musikalisches Recycling - das ist doch noch gut?!" (1) Signet Mit Nele Freudenberger – guten Morgen! Heute starten wir mit unserer Wochenreihe zum Thema „musikalisches Recycling“. Das hat in der Musikgeschichte viel größere Spuren hinterlassen als man annehmen könnte. Fremde Themen werden ausgeliehen, bearbeitet, variiert, eigene Themen wieder verwendet. Sogar eine eigene Gattung ist aus dem musikalischen Recycling hervorgegangen: das Pasticcio – und mit dem werden wir uns heute eingehender beschäftigen (0:26) Titelmelodie Ein musikalisches Pasticcio wird in Deutschland auch „Flickenoper“ genannt. Dieser wenig schmeichelhafte Name sagt eigentlich schon alles. Zum einen bezeichnet er treffend das zugrunde liegende Kompositionsprinzip: handelt es sich doch um eine Art musikalisches Patchwork, das aus alten musikalischen Materialien besteht. Die können von einem oder mehreren Komponisten stammen. Zum anderen gibt es auch gleich eine ästhetische Einordnung, denn „Flickenoper“ klingt wenn nicht schon verächtlich, so doch wenigstens despektierlich. -

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30Pm, Hall

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30pm, Hall The English Concert Harry Bicket conductor/harpsichord Iestyn Davies Rinaldo Jane Archibald Armida Sasha Cooke Goffredo Joélle Harvey Almirena/Siren Luca Pisaroni Argante Jakub Józef Orli ´nski Eustazio Owen Willetts Araldo/Donna/Mago Richard Haughton Richard There will be two intervals of 20 minutes following Act 1 and Act 2 Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 We appreciate that it’s not always possible to prevent coughing during a performance. But, for the sake of other audience members and the artists, if you feel the need to cough or sneeze, please stifle it with a handkerchief. Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel 020 3603 7930) Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight we welcome back Harry Bicket as delighted by the extravagant magical and The English Concert for Rinaldo, the effects as by Handel’s endlessly inventive latest instalment in their Handel opera music. And no wonder – for Rinaldo brings series. Last season we were treated to a together love, vengeance, forgiveness, spine-tingling performance of Ariodante, battle scenes and a splendid sorceress with a stellar cast led by Alice Coote. -

Antonio Lucio VIVALDI

AN IMPORTANT NOTE FROM Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE MAIN ARTICLE STARTING ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE: We are very pleased for you to have a copy of this article, which you may read, print or save on your computer. You are free to make any number of additional photocopies, for johnstone-music seeks no direct financial gain whatsoever from these articles; however, the name of THE AUTHOR must be clearly attributed if any document is re-produced. If you feel like sending any (hopefully favourable) comment about this, or indeed about the Johnstone-Music web in general, simply vis it the ‘Contact’ section of the site and leave a message with the details - we will be delighted to hear from you ! Una reseña breve sobre VIVALDI publicado por Músicos y Partituras Antonio Lucio VIVALDI Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Venecia, 4 de marzo de 1678 - Viena, 28 de julio de 1741). Compositor del alto barroco, apodado il prete rosso ("el cura rojo" por ser sacerdote y pelirrojo). Compuso unas 770 obras, entre las cuales se cuentan 477 concerti y 46 óperas; especialmente conocido a nivel popular por ser el autor de Las cuatro estaciones. johnstone-music Biografia Vivaldi un gran compositor y violinista, su padre fue el violinista Giovanni Batista Vivaldi apodado Rossi (el Pelirrojo), fue miembro fundador del Sovvegno de’musicisti di Santa Cecilia, organización profesional de músicos venecianos, así mismo fue violinista en la orquesta de la basílica de San Marcos y en la del teatro de S. Giovanni Grisostomo., fue el primer maestro de vivaldi, otro de los cuales fue, probablemente, Giovanni Legrenzi. -

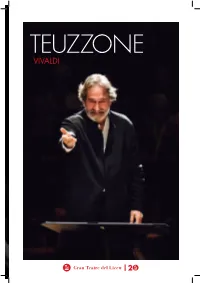

Teuzzone Vivaldi

TEUZZONE VIVALDI Fitxa / Ficha Vivaldi se’n va a la Xina / 11 41 Vivaldi se va a China Xavier Cester Repartiment / Reparto 12 Teuzzone o les meravelles 57 d’Antonio Vivaldi / Teuzzone o las maravillas Amb el teló abaixat / de Antonio Vivaldi 15 A telón bajado Manuel Forcano 21 Argument / Argumento 68 Cronologia / Cronología 33 English Synopsis 84 Biografies / Biografías x x Temporada 2016/17 Amb el suport del Departament de Cultura de la Generalitat de Catalunyai la Diputació de Barcelona TEUZZONE Òpera en tres actes. Llibret d’Apostolo Zeno. Música d’Antonio Vivaldi Ópera en tres actos. Libreto de Apostolo Zeno. Música de Antonio Vivaldi Estrenes / Estrenos Carnestoltes 1719: Estrena absoluta al Teatro Arciducale de Màntua / Estreno absoluto en el Teatro Arciducale de Mantua Estrena a Espanya / Estreno en España Febrer / Febrero 2017 Torn / Turno Tarifa 24 20.00 h G 8 25 18.00 h F 8 Durada total aproximada 3h 15m Uneix-te a la conversa / Únete a la conversación liceubarcelona.cat #TeuzzoneLiceu facebook.com/liceu @liceu_cat @liceu_opera_barcelona 12 pag. Repartiment / Reparto 13 Teuzzone, fill de l’emperador de Xina Paolo Lopez Teuzzone, hijo del emperador de China Zidiana, jove vídua de Troncone Marta Fumagalli Zidiana, joven viuda de Troncone Zelinda, princesa tàrtara Sonia Prina Zelinda, princesa tártara Sivenio, general del regne Furio Zanasi Sivenio, general del reino Cino, primer ministre Roberta Mameli Cino, primer ministro Egaro, capità de la guàrdia Aurelio Schiavoni Egaro, capitán de la guardia Troncone / Argonte, emperador Carlo Allemano de Xina / príncep tàrtar Troncone / Argonte, emperador de China / príncipe tártaro Direcció musical Jordi Savall Dirección musical Le Concert des Nations Concertino Manfredo Kraemer Sobretítols / Sobretítulos Glòria Nogué, Anabel Alenda 14 pag. -

Antonio Vivaldi from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Antonio Vivaldi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo ˈluːtʃo viˈvaldi]; 4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian Baroque composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher and cleric. Born in Venice, he is recognized as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe. He is known mainly for composing many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. Many of his compositions were written for the female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children where Vivaldi (who had been ordained as a Catholic priest) was employed from 1703 to 1715 and from 1723 to 1740. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for preferment. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died less than a year later in poverty. Life Childhood Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born in 1678 in Venice, then the capital of the Republic of Venice. He was baptized immediately after his birth at his home by the midwife, which led to a belief that his life was somehow in danger. Though not known for certain, the child's immediate baptism was most likely due either to his poor health or to an earthquake that shook the city that day. -

Opera Włoska We Wrocławiu (1725–1734) I Jej Związki Z Innymi Ośrodkami Muzycznymi

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15804/IW.2014.05.05 Walentyna Węgrzyn-Klisowska Uniwersytet Muzyczny Fryderyka Chopina w Warszawie Opera włOska we wrOcławiu (1725–1734) i jej związki z innymi OśrOdkami muzycznymi Do omówienia działalności teatru włoskiego we Wrocławiu niezbędne jest przynajmniej szkicowe przypomnienie sytuacji politycznej Śląska i uwarunkowań z tym związanych. W latach 1526–1741 cały Śląsk znaj- dował się pod panowaniem Habsburgów. W ramach monarchii austriac- kiej, na mocy postanowień pokoju zawartego w Augsburgu (1555), przy- jęto zasadę cuius regio, eius religio. Zasadę tę popierał także Kościół katolicki, reprezentowany na Śląsku głównie przez zakon jezuitów. Jego znakomicie wykształceni przedstawiciele pojawili się najpierw w Wied- niu, potem w Pradze i w Innsbrucku, a następnie w miastach śląskich, w tym także we Wrocławiu. Długo dojrzewała atmosfera sprzyjająca dominacji katolików. Przyczynili się do tego w znacznym stopniu wło- scy artyści, szczególnie za panowania cesarza Rudolfa II (1552–1612). Za panowania cesarza Macieja (1612–1619) wystawiano w języku wło- skim opery, a spektakle religijne przedstawiano w języku łacińskim. O ich realizacji decydowały władze cenzorskie, świeckie i kościelne. Opery wystawiano zwykle w karnawale, a przedstawienia religijne lub moralizatorskie (m.in. jasełka, spektakle pasyjne i alegoryczne, sacre rappresentazioni) w okresach Adwentu, Bożego Narodzenia, Wielkiego Postu i na Boże Ciało. Daty spektakli operowych wiązały się zwykle z ważnymi okolicznościami reprezentacyjnymi. Wykonawcami byli członkowie trup teatralnych. 124 Walentyna Węgrzyn-Klisowska Po raz pierwszy poza terenem Włoch, w dniu 10 lutego 1614 r., wystawiono operę włoską L’Orfeo w Salzburgu w teatrze na zamku ar- cybiskupa hr. Marcusa Sitticusa. Było to dzieło nieznanych dziś z na- zwiska twórców. -

Estreno Mundial Del Motezuma De Vivaldi

A partir del descubrimiento sobre Vivaldi más importante en los últimos cincuenta años Estreno mundial del Motezuma de Vivaldi Gabriel Pareyón Rotterdam, 15 de junio [de 2005].- El fin de semana pasado se presentó en De Doelen, considerada la sala de conciertos más importante de esta ciudad holandesa, la ópera en tres actos Motezuma (1733), de Antonio Vivaldi (1678- 1741), en versión de concierto, sin decorados ni escenografía. La interpretación, que se anunció en todo el país como “estreno mundial”, estuvo a cargo del ensamble barroco Modo Antiguo, bajo la dirección de Federico María Sardelli. En realidad la ópera se estrenó el 14 de noviembre de 1733 en el teatro Sant’Angelo de Venecia, pero con tan mala fortuna que nunca se volvió a ejecutar hasta el sábado pasado, tras 271 años de silencio. Este largo período de olvido se debió principalmente a dos causas. Una de orden musical y otra fortuita. La primera ocurrió con el estreno mismo de la obra en que, al parecer, la mezzosoprano solista Anna Girò tuvo algunos problemas para cantar. Como resultado la prima donna de Vivaldi no volvería a interpretar ninguna ópera suya, a excepción de Il Tamerlano (1735). A ello se sumó cierto malestar del público, que tal vez juzgó la pieza “demasiado seria” (pues no hay siquiera un duo de amor ni ninguna danza) y que además esperaba del compositor, en vano, algún gesto de sumisión ante la poderosa novedad del estilo de Nápoles. Éste, conocido como “estilo galante”, significaría la vuelta de página entre las tendencias veneciana y napolitana, que se tradujo en el paso del barroco hacia el clasicismo (transición que en México representó Ignacio de Jerusalem [1707-1769] frente al estilo de Manuel de Sumaya [1676-1755]). -

Vivaldi US 11/15/07 2:14 PM Page 12

660211-13 bk Vivaldi US 11/15/07 2:14 PM Page 12 Also available: VIVALDI 3 CDs Griselda Ainsworth • Huhtanen • McMurtry Nedecky • Newman • Tomkins Opera in Concert / Aradia Ensemble Kevin Mallon 8.557445 8.557852 8.660211-13 12 660211-13 bk Vivaldi US 11/15/07 2:14 PM Page 2 Antonio Aradia Ensemble VIVALDI One of the most exciting new groups to emerge in the early music world, the Toronto-based Aradia Ensemble (1678-1741) specialises in presenting an eclectic blend of orchestral, operatic and chamber music played on original instruments. The group records for Naxos, for whom it has made more than twenty recordings. They have made two music Griselda, RV718 (1735) videos, one film soundtrack, have collaborated with Isadora Duncan and Baroque dancers, have co-produced opera and worked with Balinese Gamelan. While focusing heavily on the repertoire of seventeenth-century France and Dramma per musica in Three Acts England, Aradia also performs works by the Italian and German masters of the baroque, as well as contemporary pieces commissioned by the group. In July 2000 Aradia was the featured ensemble in residence at the New Zealand Libretto by Apostolo Zeno (1668-1750), revised by Carlo Goldoni (1707-1793) Chamber Music Festival and in July 2003 performed at Musica nel Chiostro in Tuscany. According to Robert (Performing edition prepared by Kevin Mallon) Graves, Aradia was the daughter of Apollo’s twin sisters. She was sent by the gods to teach mankind to order the music of the natural world into song. Gualtiero, King of Tessaglia (Thessaly) . -

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Ospedale della Pietà in Venice Opernhaus Prag Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Complete Opera – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Index - Complete Operas by Antonio Vivaldi Page Preface 3 Cantatas 1 RV687 Wedding Cantata 'Gloria e Imeneo' (Wedding cantata) 4 2 RV690 Serenata a 3 'Mio cor, povero cor' (My poor heart) 5 3 RV693 Serenata a 3 'La senna festegiante' 6 Operas 1 RV697 Argippo 7 2 RV699 Armida al campo d'Egitto 8 3 RV700 Arsilda, Regina di Ponto 9 4 RV702 Atenaide 10 5 RV703 Bajazet - Il Tamerlano 11 6 RV705 Catone in Utica 12 7 RV709 Dorilla in Tempe 13 8 RV710 Ercole sul Termodonte 14 9 RV711 Farnace 15 10 RV714 La fida ninfa 16 11 RV717 Il Giustino 17 12 RV718 Griselda 18 13 RV719 L'incoronazione di Dario 19 14 RV723 Motezuma 20 15 RV725 L'Olimpiade 21 16 RV726 L'oracolo in Messenia 22 17 RV727 Orlando finto pazzo 23 18 RV728 Orlando furioso 24 19 RV729 Ottone in Villa 25 20 RV731 Rosmira Fedele 26 21 RV734 La Silvia (incomplete) 27 22 RV736 Il Teuzzone 27 23 RV738 Tito Manlio 29 24 RV739 La verita in cimento 30 25 RV740 Il Tigrane (Fragment) 31 2 – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Preface In 17th century Italy is quite affected by the opera fever. The genus just newly created is celebrated everywhere. Not quite. For in Romee were allowed operas for decades heard exclusively in a closed society. The Papal State, who wanted to seem virtuous achieved at least outwardly like all these stories about love, lust, passions and all the ancient heroes and gods was morally rather questionable. -

EUROPA GALANTE 19.00 H

FESTIVAL DE MÚSICA ANTIGUA DE SEVILLA Sábado, 27 de MARZO EUROPA GALANTE 19.00 h. | Teatro de la Maestranza Argippo de Vivaldi XXXVIII EDICIÓN NOTAS Aunque reconocido muy especialmente por sus aportaciones a la música instrumental, Anto- nio Vivaldi estuvo siempre obsesionado con el mundo operístico. Cuando en 1713 presentó en Vicenza Ottone in Villa, que pasa por ser su pri- mer título lírico, debería de llevar ya algunos años de vinculación con los teatros venecianos, especialmente con el Sant’Angelo, uno de los más modestos de la ciudad. Al final de su vida, Vivaldi declaró haber escrito más de 90 óperas, aunque muchas de ellas no serían sino pasticcios. De esas 90 obras se conocen 45, de las cuales se conservan en diferentes estados de integridad aproximada- mente la mitad, un balance siempre provisional, pues no dejan de producirse descubrimientos en torno a este sector del repertorio del músico. El tipo de producción operística de la época fa- vorecía la presentación de pasticcios, obras que se conformaban con aportes de arias de diversos compositores (habitualmente escritas para otras obras) que luego eran adaptadas, ensambladas y engarzadas con recitativos en la nueva historia. Haendel produjo muchos pasticcios en sus tem- poradas londinenses y Vivaldi los hizo también de forma habitual. Según Michael Talbot, Vivaldi escribió Argippo para el Teatro Kärntner Tor de Viena, donde se- guramente se vio como un intermedio en la pri- mavera de 1730. El compositor amplió después su partitura para presentarla en Praga en oto- ño de aquel mismo año, en el teatro privado del conde Sporck.