Skepticism and Expertise: the Supreme Court and the EEOC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Supreme Court of the United States

NO. In the Supreme Court of the United States JOHN HICKENLOOPER, GOVERNOR OF COLORADO, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY, Petitioner, v. ANDY KERR, COLORADO STATE REPRESENTATIVE, ET AL., Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI JOHN W. SUTHERS Attorney General DANIEL D. DOMENICO Solicitor General Counsel of Record MICHAEL F RANCISCO FREDERICK YARGER Assistant Solicitors General MEGAN PARIS RUNDLET Senior Assistant Attorney General Office of the Colorado Attorney General 1300 Broadway Denver, Colorado 80203 [email protected] 720-508-6559 Counsel for Petitioner Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i QUESTIONS PRESENTED In 1992, the People of Colorado enacted the Taxpayers’ Bill of Rights (TABOR), which amended the state constitution to allow voters to approve or reject any tax increases. In 2011, a group of plaintiffs, including a small minority of state legislators, brought a federal suit claiming that TABOR causes Colorado’s government to no longer be republican in form, an alleged violation of the Guarantee Clause, Article IV, Section 4 of the United States Constitution. The court of appeals held that the political question doctrine does not bar federal courts from resolving this kind of dispute and that the Legislator-Plaintiffs have standing to redress the alleged diminution of their legislative power. The questions presented are as follows: 1. Whether, after this Court’s decision in New York v. United States, 505 U.S. 144 (1992), Plaintiffs’ claims that Colorado’s government is not republican in form remain non-justiciable political questions. -

2010-2019 Election Results-Moffat County 2010 Primary Total Reg

2010-2019 Election Results-Moffat County 2010 Primary Total Reg. Voters 2010 General Total Reg. Voters 2011 Coordinated Contest or Question Party Total Cast Votes Contest or Question Party Total Cast Votes Contest or Question US Senator 2730 US Senator 4681 Ken Buck Republican 1339 Ken Buck Republican 3080 Moffat County School District RE #1 Jane Norton Republican 907 Michael F Bennett Democrat 1104 JB Chapman Andrew Romanoff Democrat 131 Bob Kinsley Green 129 Michael F Bennett Democrat 187 Maclyn "Mac" Stringer Libertarian 79 Moffat County School District RE #3 Maclyn "Mac" Stringer Libertarian 1 Charley Miller Unaffiliated 62 Tony St John John Finger Libertarian 1 J Moromisato Unaffiliated 36 Debbie Belleville Representative to 112th US Congress-3 Jason Napolitano Ind Reform 75 Scott R Tipton Republican 1096 Write-in: Bruce E Lohmiller Green 0 Moffat County School District RE #5 Bob McConnell Republican 1043 Write-in: Michele M Newman Unaffiliated 0 Ken Wergin John Salazar Democrat 268 Write-in: Robert Rank Republican 0 Sherry St. Louis Governor Representative to 112th US Congress-3 Dan Maes Republican 1161 John Salazar Democrat 1228 Proposition 103 (statutory) Scott McInnis Republican 1123 Scott R Tipton Republican 3127 YES John Hickenlooper Democrat 265 Gregory Gilman Libertarian 129 NO Dan"Kilo" Sallis Libertarian 2 Jake Segrest Unaffiliated 100 Jaimes Brown Libertarian 0 Write-in: John W Hargis Sr Unaffiliated 0 Secretary of State Write-in: James Fritz Unaffiliated 0 Scott Gessler Republican 1779 Governor/ Lieutenant Governor Bernie Buescher Democrat 242 John Hickenlooper/Joseph Garcia Democrat 351 State Treasurer Dan Maes/Tambor Williams Republican 1393 J.J. -

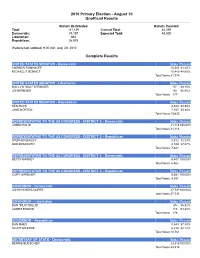

2010 Primary Electionанаaugust 10 Unofficial Results Complete Results

2010 Primary Election August 10 Unofficial Results Ballots Distributed Ballots Counted Total: 111,139 Current Total: 48,359 Democratic: 74,197 Expected Total: 48,000 Libertarian: 864 Republican: 36,078 Website last updated: 9:00 AM, Aug. 20, 2010 Complete Results UNITED STATES SENATOR Democratic Votes Percent ANDREW ROMANOFF 16,331 51.40% MICHAEL F. BENNET 15,443 48.60% Total Votes:31,774 UNITED STATES SENATOR Libertarian Votes Percent MACLYN "MAC" STRINGER 87 49.15% JOHN FINGER 90 50.85% Total Votes: 177 UNITED STATES SENATOR Republican Votes Percent KEN BUCK 8,528 54.54% JANE NORTON 7,107 45.46% Total Votes:15,635 REPRESENTATIVE TO THE US CONGRESS DISTRICT 2 Democratic Votes Percent JARED POLIS 21,116100.00% Total Votes:21,116 REPRESENTATIVE TO THE US CONGRESS DISTRICT 2 Republican Votes Percent STEPHEN BAILEY 5,512 72.33% BOB BRANCATO 2,109 27.67% Total Votes: 7,621 REPRESENTATIVE TO THE US CONGRESS DISTRICT 4 Democratic Votes Percent BETSY MARKEY 5,407 100.00% Total Votes: 5,407 REPRESENTATIVE TO THE US CONGRESS DISTRICT 4 Republican Votes Percent CORY GARDNER 5,551 100.00% Total Votes: 5,551 GOVERNOR Democratic Votes Percent JOHN HICKENLOOPER 27,731100.00% Total Votes:27,731 GOVERNOR Libertarian Votes Percent DAN "KILO" SALLIS 65 36.52% JAIMES BROWN 113 63.48% Total Votes: 178 GOVERNOR Republican Votes Percent DAN MAES 8,543 57.88% SCOTT MCINNIS 6,218 42.12% Total Votes:14,761 SECRETARY OF STATE Democratic Votes Percent BERNIE BUESCHER 23,316100.00% Total Votes:23,316 SECRETARY OF STATE Republican Votes Percent SCOTT GESSLER 12,650100.00% Total Votes:12,650 TREASURER Democratic Votes Percent CARY KENNEDY 23,630100.00% Total Votes:23,630 TREASURER Republican Votes Percent J. -

Detailed Minutes of Commission on Legal Profession Inaugural Meeting

CHIEF’S COMMISSION ON THE LEGAL PROFESSION MINUTES OF MEETING December 6, 2012 101 W. Colfax Ave., 5th Floor 3:00–5:00 PM Chief Justice Michael Bender, John Baker, Kevin Bemis, Justice Brian Boatright, Judge Russell Carparelli, Roger Clark, Sarah Clark, Jim Coyle, Al Dominguez, Katy Donnelly, Kelly Dunnaway, John Eckstein, Jake Eisenstein, Mark Fogg, Andy Frohardt, Charles Garcia, Ed Gassman, Steve Gurr, Christina Habas, Carol Haller, Tess Hand- MEMBERS IN ATTENDANCE Bender, Melissa Hart, Justice Gregory Hobbs, Chief Judge Bob Hyatt, Bruce James, Dean Marty Katz, John Kuenhold, Dave Little, Presiding Judge John Marcucci, Jerry Marroney, Judge Gale Miller, Chief Judge Michael O’Hara, Justice Nancy Rice, Christie Searls, Dave Stark, Judge Liz Starrs, Judge Dan Taubmann, Lorenzo Trujillo, Chuck Turner, John Vaught, Dan Vigil, U.S. Attorney John Walsh, Dean Phil Weiser The meeting agenda, materials, and handouts are attached to these ATTACHMENTS minutes. NEXT MEETING February 21, 2013 at 3:00 PM AGENDA ITEMS WELCOME CHIEF JUSTICE BENDER Chief Justice Bender welcomed the Honorable John Marcucci, Presiding Judge, Denver County Court, and Tess Hand-Bender of Reilly Pozner to the Commission as new Commission Members, as well as Kelly Dunnaway, Deputy County Attorney, Douglas County, as a Liaison Member representing the Colorado County Attorneys Association. REPORT FROM THE LAW SCHOOLS DEAN KATZ AND DEAN WEISER At the request of Chief Justice Bender, Dean Katz and Dean Weiser suggested three broad categories of ways the legal community can help the law schools: time, jobs, and money. They emphasized the importance of mentoring, internships, and adjunct teaching, explaining that teaching can be done individually, in teams, or simply lecturing for a course. -

News from the CBA, Local Bars, and More

TITLEAROUND | THESUB TITLEBAR | BAR NEWS News from the CBA, Local Bars, and More BY SHELBY KNAFEL Bar News is a monthly compilation of news from the CBA, including sections and committees, administration, and local and specialty bar associations. It also includes notices of activities—past, present, and future—from local and national law-related organizations and groups. DBA Docket Relaunch AILA Colorado Heads On April 24, DBA members raised a glass in honor of the newly redesigned Docket magazine, to the Supreme Court which features a sleek design and fresh content. The relaunch party was hosted at the Denver On April 15, a group of lawyers from the Col- Press Club. orado Chapter of the American Immigration Lawyers Association were sworn in to the Bar of the U.S. Supreme Court. The group 1 Clair Smith, graphic designer, with Ray Ruth, owner of Photographic Print later spoke with members of Congress about Services. modernizing immigration laws. 2 Anthony Perreira and Docket editor Brendan Baker. 1 1 2 1 Front row: Jeff Joseph, Kathleen Gilbert- Macmillan, Nicole Murad Rothstein, Allen Orr (Movant), Christina Fiflis, Jennifer Smith, and Aaron Elinoff. Back row: Alex McShiras, Bryon M. Large, Shawn Meade, and James Lamb. 2 The immigration lawyers traveled to DC to speak before Congress. 2 46 | COLORADO LAWYER | JUNE 2019 Barristers Benefit Ball The Denver Bar Association held its annual Barristers Benefit Ball on Friday, April 12. The Roaring Twenties-themed event was held at Mile High Station, where guests entered through a “speakeasy.” The gala is the annual fundraiser for Metro Volunteer Lawyers, which recruits and coordinates volunteer attorneys to represent people who otherwise could not afford legal assistance. -

2020 Abstract of Votes Cast

2020 Abstract of Votes Cast Office of the Secretary of State State of Colorado Jena Griswold, Secretary of State Christopher P. Beall, Deputy Secretary of State Judd Choate, Director of Elections Elections Division Office of the Secretary of State 1700 Broadway, Suite 550 Denver, CO 80290 Phone: (303) 894-2200, ext. 6307 Official Publication of the Abstract of Votes Cast for the Following Elections: 2019 Odd-Year 2020 Presidential Primary 2020 Primary 2020 General Dear Coloradans, It is my privilege to present the biennial election abstract report, which contains the official statewide election results for the 2019 coordinated election, 2020 presidential primary, 2020 statewide primary, and 2020 general election. This report also includes voter turnout statistics and a directory of state and county elected officials. The Colorado Secretary of State’s Election Division staff compiled this information from materials submitted by Colorado’s 64 county clerk and recorders. Additional information is available at Accountability in Colorado Elections (ACE), available online at https://www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/elections/ACE/index.html. Without a doubt, the 2020 election year will be remembered as one of our state’s most unusual and most historic. After starting with the state’s first presidential primary in 20 years, we oversaw two major statewide elections amidst a global pandemic and the worst forest fires in Colorado’s history. Yet, despite those challenges, Colorado voters enthusiastically made their voices heard. We set state participation records in each of those three elections, with 3,291,661 ballots cast in the general election, the most for any election in Colorado history. -

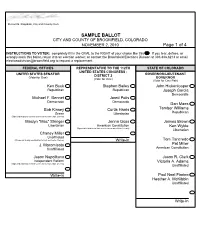

Test Ballot Print Document

Russell G. Ragsdale, City and County Clerk SAMPLE BALLOT CITY AND COUNTY OF BROOMFIELD, COLORADO NOVEMBER 2, 2010 Page 1 of 4 INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTER: completely fill in the OVAL to the RIGHT of your choice like this If you tear, deface, or wrongly mark this ballot, return it to an election worker; or contact the Broomfield Elections Division at 303.438.6213 or email [email protected] to request a replacement. FEDERAL OFFICES REPRESENTATIVE TO THE 112TH STATE OF COLORADO UNITED STATES CONGRESS - GOVERNOR/LIEUTENANT UNITED STATES SENATOR DISTRICT 2 (Vote for One) GOVERNOR (Vote for One) (Vote for One Pair) Ken Buck Stephen Bailey John Hickenlooper Republican Republican Joseph Garcia Democratic Michael F. Bennet Jared Polis Democratic Democratic Dan Maes Bob Kinsey Curtis Harris Tambor Williams Green Libertarian Republican (Signed delcaration to limit service to no more than 2 terms) Maclyn "Mac" Stringer Jenna Goss Jaimes Brown Libertarian American Constitution Ken Wyble (Signed declaration to limit service to no more than 3 terms) Libertarian Charley Miller Unaffiliated (Chose not to sign declaration to limit service to 2 terms) Write-in Tom Tancredo J. Moromisato Pat Miller Unaffilliated American Constitution Jason Napolitano Jason R. Clark Independent Reform Victoria A. Adams (Signed declaration to limit service to no more than 2 terms) Unaffiliated Write-in Paul Noel Fiorino Heather A. McKibbin Unaffiliated Write-in Page 2 of 4 SECRETARY OF STATE STATE REPRESENTATIVE - Shall Judge Katherine R. Delgado of (Vote for One) DISTRICT 33 the 17th Judicial District be retained in (Vote for One) office? Scott Gessler Donald Beezley YES NO Republican Republican Shall Judge Thomas R. -

Chief's Commission on the Legal Profession

CHIEF’S COMMISSION ON THE LEGAL PROFESSION MINUTES OF MEETING December 1, 2011 101 W. Colfax Ave., 5th Floor 3:00–5:00 PM Chief Justice Michael L. Bender, John T. Baker, Chief Judge Roxanne Bailin, Judge Russell E. Carparelli, Associate Dean Fred Cheever, Roger E. Clark, Sarah M. Clark, Professor Roberto Corrada, John A. Eckstein, Mechelle Y. Faulk, Mark A. Fogg, Judge Richard L. Gabriel, Charles Garcia, Ed Gassman, John S. Gleason, Professor Melissa Hart, Diego G. Hunt, Chief Judge John Kuenhold, Assistant Dean Whiting ATTENDEES Dimock Leary, William Leone, Michael G. Massey, David C. Little, John E. Mosby, Chief Judge Michael A. O'Hara III, Margrit Lent Parker, David W. Stark, Chief Judge William B. Sylvester, Lorenzo Trujillo, Mimi E. Tsankov, Charles Turner, Kara Vietch, Daniel A. Vigil, U.S. Attorney John Walsh, and Dean Philip J. Weiser were in attendance. ATTACHMENTS The meeting agenda and materials are attached to these minutes. NEXT MEETING February 23, 2012 at 3:00 PM AGENDA ITEMS WELCOME CHIEF JUSTICE BENDER Chief Justice Bender observed a common theme emerging from the Working Groups: service to others. He explained that serving others is a steadfast value that ties together the members of the legal profession. He remarked that serving others has been the underlying goal of many of the Commission’s proposals and projects: such as Working Group B’s Colorado Lawyers for Colorado Veterans initiative and Working Group D’s focus on access to justice. He concluded that reinvigorating the legal profession’s common regard for serving others certainly supports and furthers the Commission’s objectives. -

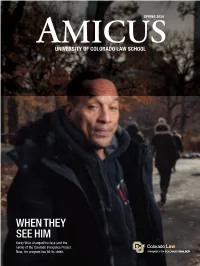

WHEN THEY SEE HIM Korey Wise Changed the Face (And the Name) of the Colorado Innocence Project

WHEN THEY SEE HIM Korey Wise changed the face (and the name) of the Colorado Innocence Project. Colorado Law Now, the program has hit its stride. UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER Spring 2020 3 Message from the Dean A Tradition of Public Service As this issue of Amicus goes to press, we are experiencing many changes due to the impact of COVID-19. We have switched to fully remote classes for the rest of the semester, and are exploring alternative ways of celebrating the Class of 2020 in the wake of a canceled in-person May commencement ceremony. These are trying times, and I am proud of the resiliency and care for one another that our community has shown. Amid everything going on in the world, we still have much to celebrate, as we are reminded in the following pages. I hope this issue of Amicus inspires you. Public service is a key component of a lawyer’s professional obligations and an essential ingredient in a legal career. As a law school, we are committed to instilling an ethic of public service in our students and graduates. Personally, public service has been one of the most satisfying aspects of my career. Last year, our students spent a total of 14,291 hours assisting the underserved through our nine legal clinics. More than 92 percent of 1Ls signed the Public Service Pledge, and the members of the Class of 2019 collectively contributed over 6,700 hours of unpaid law-related service during their time in law school. On top of providing valuable experience through clinics and externships, we have introduced several public service projects led by faculty members. -

Fourth Amended Substitute Complaint, Filed

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO Civil Action No. 11-cv-1350-RM-NYW ANDY KERR, COLORADO STATE SENATOR; NORMA V. ANDERSON; JANE M. BARNES; K.C. BECKER, COLORADO STATE REPRESENTATIVE; ELAINE GANTZ BERMAN; BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OF BOULDER COUNTY; BOULDER VALLEY SCHOOL DISTRICT RE-2 BOARD OF EDUCATION; ALEXANDER E. BRACKEN; WILLIAM K. BREGAR; BOB BRIGGS; BRUCE W. BRODERIUS; TRUDY B. BROWN; STEPHEN A. BURKHOLDER; RICHARD L. BYYNY, M.D.; CHEYENNE WELLS RE-5 SCHOOL DISTRICT BOARD OF EDUCATION; COLORADO SPRINGS DISTRICT 11 BOARD OF EDUCATION; LOIS COURT, COLORADO STATE SENATOR; DENVER COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS BOARD OF EDUCATION; RICHARD E. FERDINANDSEN; STEPHANIE GARCIA; GUNNISON COUNTY METROPOLITAN RECREATION DISTRICT; GUNNISON WATERSHED RE-1J SCHOOL DISTRICT BOARD OF EDUCATION; CHRISTOPHER J. HANSEN, COLORADO STATE REPRESENTATIVE; KRISTI HARGROVE; LESLIE HEROD, COLORADO STATE REPRESENTATIVE; DICKEY LEE HULLINGHORST; NANCY JACKSON; WILLIAM G. KAUFMAN; CLAIRE LEVY; SUSAN LONTINE, COLORADO STATE REPRESENTATIVE; MARGARET (MOLLY) MARKERT; MEGAN J. MASTEN; MICHAEL MERRIFIELD, COLORADO STATE SENATOR; MARCELLA (MARCY) L. MORRISON; JOHN P. MORSE; PAT NOONAN; BEN PEARLMAN; POUDRE SCHOOL DISTRICT BOARD OF EDUCATION; PUEBLO CITY DISTRICT 60 BOARD OF EDUCATION; PUEBLO COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT 70 BOARD OF EDUCATION; WALLACE PULLIAM; PAUL WEISSMANN, BOULDER COUNTY TREASURER; and JOSEPH W. WHITE; Plaintiffs, v. JOHN HICKENLOOPER, GOVERNOR OF COLORADO, in his official capacity, Defendant. FOURTH AMENDED SUBSTITUTE COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE AND DECLARATORY RELIEF I. OPENING STATEMENT 1. This case presents for resolution the contradiction between direct democracy and representative democracy. In 1992, Colorado voters adopted by initiative the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (the “TABOR Amendment”), removing from the Colorado General Assembly and all subordinate levels of government the power to tax and arrogating that power exclusively to themselves. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 14-460 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States JOHN HICKENLOOPER, GOVERNOR OF COLORADO, IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY, Petitioner, v. ANDY KERR, COLORADO STATE REPRESENTATIVE, et al., Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI MICHAEL F. FEELEY DAVID E. SKAGGS CARRIE E. JOHNSON Counsel of Record SARAH MAY MERCER CLARK LINO S. LIPINSKY DE ORLOV BROWNSTEIN HYATT HERBERT LAWRENCE FENSTER FARBER SCHRECK LLP MCKENNA LONG 410 17th Street, Suite 2200 & ALDRIDGE LLP Denver, CO 80202-4437 1400 Wewatta Street (303) 223-1100 Suite 700 Denver, CO 80202 MICHAEL BENDER (303) 634-4000 PERKINS COIE LLP [email protected] 1900 Sixteenth Street, Suite 1400 Denver, CO 80202-5255 (303) 291-2300 JOHN A. HERRICK 2715 Blake Street, Suite 9 Denver, CO 80205 (720) 987-3122 Counsel for Respondents November 21, 2014 i QUESTIONS PRESENTED Whether there are compelling reasons for this Court to review the Tenth Circuit’s unanimous interlocutory opinion affirming the District Court’s rulings: (i) that none of the Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), political question factors requires dismissal of the Respondents’ narrowly tailored Guarantee Clause challenge to Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights; and (ii) that the state legislator Respondents have alleged a concrete, institutional injury-in-fact sufficient to satisfy the requirements of legislative standing set forth in Coleman v. Miller, 307 U.S. 433 (1939), and later refined in Raines v. Byrd, 521 U.S. 811 (1997). ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING AND CORPORATE DISCLOSURE No party to this proceeding is a corporation. -

ANGELA M. VICHICK Associate

ANGELA M. VICHICK Associate [email protected] D: 303.628.9559 Denver Angela Vichick is a litigator who represents individual and institutional clients in Practices various complex civil disputes. Angela’s practice focuses on business and real estate ■ Appellate litigation involving business tort, contract, civil theft, derivative, fiduciary, fraud, ■ Litigation and Disputes fraudulent/preferential transfer, interpleader, probate, receivership, and quiet title ■ Real Estate Litigation claims (e.g., those involving adverse possession, easements, foreclosure, and ■ Banking and Lending Disputes spurious documents). Angela’s extensive advocacy experience includes dispositive ■ Business Torts and Partnership motions practice, evidentiary hearings, settlement proceedings, arbitrations, bench Disputes and jury trials, post-trial proceedings and enforcement of judgments, as well as appeals before the Colorado Court of Appeals, Colorado Supreme Court, and the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. Prior to joining the firm, Angela’s practice was based in Aspen, Colorado, before she was invited to serve as an inaugural law clerk and judicial assistant for Justice Melissa Hart of the Colorado Supreme Court. Personal Approach Clients turn to Angela for her strategic approach to evaluating claims and collateral legal issues, in addition to her ability to optimize case management and decision- making during each phase of litigation. Angela is known for her tenacity in seeking out solutions to legal issues, as well as her writing abilities. Angela is also an active member of both the Denver and Roaring Fork Valley communities. Passionate about education, housing stability, and small business issues, Angela is a frequent CLE presenter and guest lecturer on those topics, regularly provides related pro bono services, and is a lead high school mock trial www.lewisroca.com ANGELA M.