Harmony Booklet.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinghy Racing Claremont Series 2019

HOWTH YACHT CLUB DINGHY RACING CLAREMONT SERIES 2019 SAILING INSTRUCTIONS 1. Rules 1.1 Racing will be governed by the Racing Rules of Sailing, the prescriptions of the Irish Sailing Association, the Sailing Instructions (SI) and any amendments thereto. 1.2 Competitors are reminded of Fundamental Rule 2, Fair Sailing. Fair Play and Sportsmanship are important parts of our sport. 2. Notices Notices will be posted on the Notice Board. The Notice Board is beside the pedestrian gate at the Marina Office. 3. Changes to Sailing Instructions Any change to the Sailing Instructions will be posted on the Notice Board not less than 2 hours before the first race it will affect. 4. Signals 4.1 Signals made ashore will be displayed on the flag pole at the top of the marina bridge. 4.2 When flag “AP” is displayed ashore “1 minute” is replaced with “Not less than 30 minutes” in the race signalled AP. 5. Schedule of Races 5.1 Dates and times of racing: Where possible, it is proposed to sail two races per day Dates Warning Signal Sunday 15 September 2019 10.25 Sunday 22 September 2019 10.25 Sunday 29 September 2019 10.25 Sunday 06 October 2019 10.25 Page | 1 HOWTH YACHT CLUB DINGHY RACING CLAREMONT SERIES 2019 SAILING INSTRUCTIONS 6. Class Flags Laser class Flag Sundry Flag F Optimist Flag O 7. Racing Area The race area will be North West of Howth Harbour 8. Courses 8.1 Course type to be indicated with Flag – T for Triangle and W for Windward-Leeward. -

The Racing Rules of Sailing $2

THE RACING RULES OF SAILING 2013 – 2016 with Jan. 2013 changes: many. * for bulk changes, Underline for small additions and strike through for small omissions. including Sailing Instructions for Sunday Dinghy Races Note: This is an abridged version of the RRS Cal Sailing Club 124 University Ave. Berkeley, CA 94710 International Sailing Federation 2013 Edition http://www.sailing.org/rrs CONTENTS SPORTSMANSHIP AND THE RULES________________________4 ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSIBILITY_______________________4 PART 1 – FUNDAMENTAL RULES_________________________5 PART 2 – WHEN BOATS MEET___________________________5 PART 3 – CONDUCT OF A RACE__________________________8 PART 4 – OTHER REQUIREMENTS WHEN RACING__________10 PART 5 – PROTESTS, REDRESS, HEARINGS, MISCONDUCT AND APPEALS___________________12 APPENDIX S SOUND-SIGNAL STARTING SYSTEM___________16 DEFINITIONS________________________________________17 SAILING INSTRUCTIONS_______________________________19 Note: The following sections are not included in this booklet, as they are rarely or never applicable to CSC Sunday dinghy racing, and/or supplanted by Sailing Instructions guidance: 26 Starting Races 30 Starting Penalties 33 Changing the Next Leg of a Course 43 Competitor Clothing & Equipment 45 Hauling Out; Making Fast; Anchoring 48 Fog Signals and Lights 49.2 (lifelines) 50 Setting and Sheeting Sails 51 Movable Ballast 52 Manual Power 53 Skin Friction 54 Forestays and Headsail Tacks 61.3 and 62.2 Protest time limits (superseded by Sailing Instructions) 64.3 Decisions on Measurement Protests 65.3 Protests pertaining to measurement rule. 69 Allegations of Gross Misconduct (superseded by CSC rules) 70 Appeals to national authority, and 71 National authority decisions 75 – 91 All sections superseded by Sailing Instructions or CSC rules All appendices are omitted except for certain portions of S (see Contents, above). Basic Principles SPORTSMANSHIP AND THE RULES Competitors in the sport of sailing are governed by a body of rules that they are expected to follow and enforce. -

Cadet Dinghy

Cadet Dinghy “Viking” Appendix 2 THE CADET SQUADRON In the early 1930's, Cadet Members of the R.G.Y.C. competed in a conglomeration of small craft. Ern Armstrong recalls that when he joined the club in 1933, the cadet section was comprised of the 12 foot cadets, "Firey Cross", owned and sailed by John Boocock, on which Ern sailed for the last three races of the season and "Viking", owned by Tal and Jim Searle, "Tasma", a flat-bottomed ,low wooded hull approximately 14feet long, owned by the Club, "Teddy bear", a half-decked rather heavy boat owned by Geoff Wood, and "Westra", a semi-decked 12 foot cadet, owned by the McAllisters. At that time the boat storage shed was approximately 40 feet by 30 feet fronting the roadway outside the club opposite Transvaal Square, about in line with the eastern end of the present Junior Squadron clubhouse. In about 1935, two 14 foot boats were added to the fleet. These were "Mulluka", owned by Chick Fleet Snr., and sailed by Jim Ritchie and "NV", a 14footer with narrow beam and a high aspect mainsail built and skippered by Norm Wray. And two more 12 foot cadet dinghies were also added to the fleet, "Caress", built and skippered by Bob Curnow and "Dolphin ", owned and skippered by Wally Wiggs. About this time the Cadet section acquired half of the Sea Scout's shed owned by Mr. Ev Hurst, now the tender dinghy storage shed. This move avoided the long lift from the original shed on the roadway. -

Up River Yacht Club Dinghy Duties and Sailing

UP RIVER YACHT CLUB DINGHY DUTIES AND SAILING INSTRUCTIONS January 2017 1 FLAG OFFICERS See handbook SAILING COMMITTEE See handbook 2 DINGHY RACE EQUIPEMENT All Equipment for race duties is stored in the Race Box. RACE BOX KEY A key to the Race Box is kept in the wall box outside the Female Changing Room and a spare key is kept on the Key Board in the Office. SAFETY BOAT KEYS Engine security chain keys are kept in the wall box outside the Female Changing Room. Ignition Keys for Safety Boats are to be left in the Safety boats. Both Key Box and Boat shed are now combination entry. See a member of the committee for the number. See Appendix 1 for description of Race Officer and safety Boat Duties. DINGHY PARK Please note: It is incumbent upon each member to keep the area of the dinghy park under and around their boat(s) tidy and grass trimmed. Members must also tie down their dinghies in at least two, preferably three, fixing points in the ground (i.e. stakes). This is a minimum requirement of most insurance companies. It is compulsory for every Dinghy owner to attend the Dinghy Park Work Party. This will be in addition to the attendance of at least one House Work Party. 3 RACE DUTIES To enable both Slow Handicap Course and Course races to be held with adequate safety boat cover, five Club Members are required for duty for every Club race day described as Winter or Warm up Series as two safety boats are required. -

Introduction to the Championship

Introduction to the Championship Optimist Fleet at CGSC The Optimist is the world’s most popular youth sailing trainer in existence with over 150,000 vessels registered with the class association. The Optimist is sailed in over 120 countries and it is one of only two dinghies approved by World Sailing exclusively for sailors under 16 years of age. At the London Olympics in 2012, 80% of all boat skippers were former Optimist sailors, most of them having reached international level in the Class. So congratulations! You are part of a rich and great international tradition here at CGSC, and you have a lot to look forward to stepping into the competitive world of Optimist Racing. But first, what is the Championship Fleet at CGSC? Red, White, and Blue Explained Within the Optimist Circuit, the competitors are divided in Fleet Racing (more on that later) by age into three divisions. Sailors fall into the different fleets based on age, not skill level White 10 years old or under Blue 11 to 12 years old Red 13 to 15 years old In the United States the Optimist Class is overseen by the USODA (United States Optimist Dinghy Association) and they host sanctioned regattas all over the United States (USODA Qualifiers). Our ultimate goal in the CGSC Championship Optimist Fleet is to qualify for the World Championship one day. It is the highest honor an Optimist sailor can receive, and only 5 sailors are allowed into the Worlds per country. CGSC has the distinction of being the only club to send almost all the sailors representing the US two years in a row! (1984 and 1985 optimist worlds) so the potential for success in Optimist Racing is there. -

FEATURED: MULTIHULL FLEET Summer Is Behind Us for the Year As We Approach Fall

AUSTIN YACHT CLUB TELLTALE September 2020 Sailing during Covid-19 Sail safe, stay healthy! Message from the Commodore Hopefully the heat of the FEATURED: MULTIHULL FLEET summer is behind us for the year as we approach fall. The City and County have recently moved from Covid Stage 4 Restrictions to Stage 3, and hopefully to Stage 2 soon. Unfortunately, given the orders from the City and County that limit gatherings, we have had to cancel the Annual Banquet for this year. Given the lack of sailing and other activity this year, we have also decided not to present most of the Annual Awards. In place of the Sailing Awards, we are asking for nominations for Special Service to the Club Awards for those who have gone above and beyond during this crazy year. Nominations can be submitted via the website. More details in this issue. The Board will review the nominations and make selections. However, take heart, the Blue Duck Award will be presented at the Annual Membership Meeting along with the Special Service Awards. The Blue Duck nomination form is also on the website. The Board is planning a couple of Covid-compliant regattas for the weekends of October 10th and 17th. See Vice Commodore Diane Covert’s column for more details. As of now, the Skippers meetings will be via Zoom before the regatta, and trophies acknowledged by Zoom afterwards. More details online and in this issue of the Telltale. Although we have had some much needed rain, not much of it has ended up in the lake, so look for dock moves starting very soon. -

Blast Reaching at the NSW States Photos Neil Waterman ©

Blast Reaching at the NSW States Photos Neil Waterman © Volume 153 June 2006 NS14 Bulletin President’s Message First of all I would like to introduce myself to those who don’t know me as by virtue of being elected NSW President I am also the National President under the current constitution. This will change under the proposed revisions to the constitution whereby the President will be elected. I have been in NSs for 20 years mainly based at Northbridge although I have moved in and out of the Association as Hugh and Penny’s boat interests have changed (eg FAs, Lasers, MGs, 29ers, 16’ skiffs, and yachts). This has allowed me to have some exposure as to how other classes are run. For the last couple of seasons we have had three NSs in the family and I am keen to see the class get back to the strength it had a number of years ago. In this context I would like to outline a number of actions I think we need to take to help rejuvenate the class and bring the numbers participating at a class level back to where we used to be. There is no doubt there is a lot more competition for people’s time nowadays, but I feel that we have an opportunity to position this class as a great way for people to use the time they have. The key challenges are to get people sailing in regattas and to get people building new boats again. First, I think we need to market the NS14 using the strengths of the class to demonstrate that this class will suit a broad spectrum of sailors. -

April/May, 2020

APRIL/MAY, 2020 The cover photo is inspired from Dawn—Michelle Oliver’s book review in the March Issue of this Newsletter. Obviously this is not Lake Townsend. Considering the lack of racing photographs from our own club,’s abbreviated racing schedule, the photo below is from a past Veendee Globe race which happens every four years . It is actually scheduled to begin again this year, on Sunday, November 8. Considering there is already social distancing in this race, it will probably happen on Schedule. See page 6 for more information. PAGE 2 TELL TALES A Note From the Commodore Ahoy Sailors! I am sure that all are keeping safe by observing distancing, droplet protection, hand washing and isolation recommendations. How- ever, these recommendations made it a real challenge and stressor to not physically connect with our family, friends, and neighbors during the Easter and Passover holiday times. I am very grateful to be living in a time when technology can mitigate some of the isola- tion I feel. Last night, I experienced a 10 location Zoom group din- ner event that that helped me feel connected to my family in this difficult situation. People in large cities are breathing clean air and seeing mountain views that have not been seen for years. That is a good sign show- ing how quickly the earth recovers when less pollution is created. Let’s look for whatever good we can find in this crisis and help make society better for it. We will move past this pandemic and return to sailing! AnnMarie Commodore LTYC PAGE 3 TELL TALES Editor’s note: Our club is full of members with vast knowledge and in this monthly article, Eric & Joleen will share theirs. -

Och Kapacitetsanalys

Krav- och kapacitetsanalys - Segling Per Frykholm GYMNASTIK- OCH IDROTTSHÖGSKOLAN Kurs: Träningslära 1 Ht-2007 Handledare: Mårten Fredriksson, Lee Nolan Innehålls förteckning 1. Inledning...........................................................................................1 2. Bakgrund ..........................................................................................1 3. Syfte .................................................................................................1 4. Metod................................................................................................2 5. Resultat.............................................................................................2 5.1 Seglargymnasiet .............................................................................2 5.2 Elitklubbarna ..................................................................................4 5.3 Landslaget ......................................................................................5 5.4 Sveriges olympiska kommitté – topp- och talangprogram .............7 6. Diskussion ........................................................................................8 6.1 Seglargymnasierna .........................................................................8 6.2 Elitklubbarna ..................................................................................8 6.3 Landslaget ......................................................................................9 6.4 Sok................................................................................................10 -

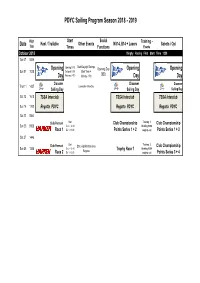

PROG PDYC 2018-19.Xlsx

PDYC Sailing Program Season 2018 - 2019 High Start Social Training - Date Keel / Trailable Other Events NS14, B14 + Lasers Sabots / Opi Tide Times Functions Events October 2018 Dinghy Racing First Start Time 1330 Sat 07 0829 Start Daylight Savings Opening Opening 1300 Opening Day Opening Opening Sun 07 1028 Sail past 1350 Start Term 4 BBQ Day First race 1410 Monday 15th Day Day Discover Discover Discover Thur 11 1437 Launceston Show Day Sailing Day Sailing Day Sailing Day Sat 13 1618 TSSA Interclub TSSA Interclub TSSA Interclub Sun 14 1702 Regatta PDYC Regatta PDYC Regatta PDYC Sat 22 0854 Club Pennant Start Club Championship Training 1 Club Championship Sun 23 0938 Div 2 - 12:40 Briefing 10:00 Race 1 Div 1 -13:00 Points Series 1 + 2 ready to sail Points Series 1 + 2 Sat 27 1446 Training 2 Club Pennant Start DSC High Performance Club Championship Sun 28 1536 Div 2 - 12:40 Briefing 10:00 Regatta Trophy Race 1 Race 2 Div 1 -13:00 ready to sail Points Series 3 + 4 PDYC Sailing Program Season 2018 - 2019 High Start Social Training - Date Keel / Trailable Other Events NS14, B14 + Lasers Sabots / Opi Tide Times Functions Events November 2018 Dinghy Racing First Start Time 1330 Sat 03 0820 Long BMW Showdown Regatta TSSA Southern Sun 04 0912 RYCT Regatta RYCT Mon 05 1008 Weekend Long Weekend Long Weekend Function at Sat 10 1459 see NOR Doyle Inshore PDYC Champs Sun 11 1545 No Dinghy Racing No Dinghy Racing Elliott 5.9 States Fri 16 1900 Function at Sat 17 0736 see NOR PJ Super Series THE CLASSIC PDYC Club Pennant Start Club Championship Training -

Dinghy Sailing Instructions

EXE SAILING CLUB Tornado, Shelly Road, Exmouth, EX8 1EG Tel: 01395 264607 email: [email protected] website: exe-sailing-club.org Sailing Instructions - Dinghy Racing Document History Reviewed and approved by the Exe Sailing Club (ESC) Sailing Committee. Updated: 27/03/2018 (Version 1.11 – Anne Way) These Sailing Instructions apply to all dinghy races run by Exe Sailing Club unless event specific Sailing Instructions are produced. Document governance The Dinghy Committee reviews and where necessary updates the club Dinghy Sailing Instructions annually to reflect the implementation of the current Racing Rules of Sailing, the RYA Arbitration process and any local variation of these in our club racing. The Dinghy Committee shall then submit the updated Sailing Instructions to the Sailing Committee to be approved before the start of the racing season. For avoidance of any doubt the Race Committee and the Sailing Committee are deemed to be the same body. Please notify the Sailing Committee of any errors or omissions you find in either copy of the Sailing Instructions. This is best done via email to the Chair of the Sailing Committee. Page 1 of 17 RYA Racing Charter Objectives • To provide the framework for everyone to enjoy the sport of sailboat racing in whatever capacity and to whatever level the individual desires. • To ensure that the sport of sailboat racing welcomes all people and treats them equally. • To ensure that those who experience sailboat racing are encouraged to continue. Principles and Practices • The sport welcomes all participants; it relies largely on self-compliance and self-policing. -

470 Etimes Issue: Dec Ember 2009

470 Worlds Stats Men‘s 470 Top 10 10 nations/4 continents Women‘s 470 Top 10 9 nations/4 continents :: Page 8 Joe Glanfield: —I love the 470. It‘s a boat that incorporates every aspect of dinghy racing.“ :: Page 4 Photo: Sander van der Borgh 470 ETIMES ISSUE: DEC EMBER 2009 Photo: Getty Images WWW.470.ORG 470 ETIMES The eTimes is the official newsletter of the International 470 Class Association All rights reserved: 470 Internationale© DISTR IBUTION Beijing 2008 Women‘s 470 bronze medallist Isabel Swan and World‘s best - National Class Associations - Sailing Federations soccer player Pele support Rio de Janeiro‘s bid for the 2016 Olympics. - 470 sailors & spectators WHAT THE BEIJING M EDALLISTS DID NEXT? - (Sailing) Sport Media ANDY RICE CAUGHT UP WITH THE 470 OLYMPIC M EDALLISTS FROM BEIJING - ISAF :: P AGE 3-4 The 470 eTimes is distributed 470 ET IMES INDEX through the International 470 WORDS FROM THE PRESIDENT Class emailing list, and through 470 CLASS SAILORS‘ SUPPORT PRORAMMES the official 470 Class web site: ñ WHAT HAPPENNED AFTER BEIJING ? MORE PROGRAMMES, www.470.org ñ SAILOR’S SU PPORT PROGRAMME S ñ CHAMPIONSHIP REVIEW S INCREASING GLOBAL EXPA NSION. P HOTOGRAPHY With many thanks to: ñ MASTERS AND LEGENDS The International 470 Class offers more Support programmes, more knowledge transfer and more support to sailors‘ Olympic campaigns. - Getty Images ñ ISAF WORLD CU P - Sander van der Borgh - Thom Touw ñ ATHLETES’ COMMISSION ñ CALENDAR :: P AGE 5 -6 EDITORIAL: ñ OLYMPIC Q U ALIFICATION Contributions of Luissa Smith ñ 470 ATHLETES Andy Rice Rick van Wijngaarden WOMEN‘S SA ILING - WORLDS‘ FLEET T OP 20 Edward Ramsden Five 420 Ladies‘ World Championship medallists, two 470 ATHLETES Hubert Kirrmann out of three girls who have ever won the overall Top players in the International 470 Nicholas Guichet Class.