Understanding Child Neglect Through Selected Works by Jacqueline Wilson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacqueline Wilson Dream Journal Ebook Free Download

JACQUELINE WILSON DREAM JOURNAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jacqueline Wilson, Nick Sharratt | 240 pages | 03 Jul 2014 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780857534316 | English | London, United Kingdom Jacqueline Wilson Dream Journal PDF Book The three girls have been best friends forever, but now Ellie is convinced she's fat, Nadine wants to be a model, and Magda worries that her appearance is giving guys the wrong idea. Em adores her funny, glamorous dad - who cares if he's not her real father? The Diary of a Young Girl. Lily Alone. I Am Sasha. Have you ever wondered what happened to Tracy Beaker? All rights reserved. This was also the first of her books to be illustrated by Nick Sharratt. See More. Friend Reviews. For me, books like this have to exist so that novels covering the more unusual family or young lives of the time can actually be compared with something. Lucky for Mum, because now she's got the flu, so I've got to mind her - and help with all the babies! Isabella Torres rated it it was amazing Oct 27, Rent a Bridesmaid. Jacqueline Wilson Biscuit Barrel. Abschnitt 8. It was a fascinating book and portions of it made me laugh loudly. Log In. The Worry Website. You have no items in your shopping cart. My Secret Diary: Dating, Dancing, Dreams and Dilemmas Best-loved author Jacqueline Wilson continues the captivating story of her life with this gripping account of her teenage years — school life, first love, friends, family and everything! Beauty and her meek, sweet mother live in uneasy fear of his fierce rages, sparked whenever they break one of his fussy house rules. -

GARY PARKER Writer

GARY PARKER Writer 2021 OPAL MOONBABY TV adaptation of series of children’s books by Maudie Smith in development 2020-21 FLATMATES (SERIES 2) Lead writer and writer of 3 x episodes Produced by Zodiak for BBC 2020 EJ12 – GIRL HERO Pilot script in development with Ambience Entertainment 2019 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SPECIALS) Wrote 2 x special episodes Produced by Zodiak for CBBC 2017-18 MILLE INBETWEEN (SERIES 4) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 4 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2016 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SERIES 3) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 4 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2015 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SERIES 2) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 5 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2013-14 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SERIES 1) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 7 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2013 DANI’S CASTLE 2 episodes for RDF Television/Foundation TV 2012 JILLY COOPER ADAPTATION 100 minute TV film adaptation of a Jilly Cooper novel Cooperworld (Neil Zeiger / Greg Boardman) 2010-12 DANI’S HOUSE 7 episodes for RDF Television/Foundation TV 2011 CAMPUS Wrote Pilot and Series 1. Moniker Pictures/Channel 4 DELIVERANCE Team writing for 60 minute comedy drama and series for Company/Channel 4 BEN & HOLLY’S LITTLE KINGDOM 10 x 11 minute scripts for Elf Factory/Nick Jnr and Five Milkshake 2010 FREAKY FARLEYS 3 x 22 minute script for RDF Television/Foundation TV TATI’S HOTEL 2 x 11 minute script for Machine Productions 2009 MUDDLE EARTH 2 x 11 minute animated script for CBBC DANI’S HOUSE 3 x 22 minute script for RDF Television/Foundation TV MYTHS REWIRED 6 x 1 hour series in development with Lime Pictures MIRROR MIRROR 1 x 30 minute episode for BBC3 CAMPUS Pilot for Moniker Pictures Ltd/Channel 4 GASPARD ET LISA Two episodes for Chorion UK 2008 SCHOOL OF COMEDY Sketches for Series, Leftbank/Channel 4. -

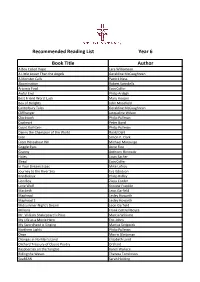

Recommended Reading List Year 6 Book Title Author

Recommended Reading List Year 6 Book Title Author A Boy Called Hope Lara Williamson A Little Lower Than the Angels Geraldine McCaughrean A Monster Calls Patrick Ness Abomination Robert Swindells Artemis Fowl Eoin Colfer Awful End Philip Ardagh Best Friend Worst Luck Mary Hooper Box of Delights John Masefield Canterbury Tales Geraldine McCaughrean Cliffhanger Jacqueline Wilson Clockwork Philip Pullman Cogheart Peter Bunzl Count Karlstein Philip Pullman Danny the Champion of the World Roald Dahl Eren Simon P. Clark From Hereabout Hill Michael Morpurgo Goggle Eyes Anne Fine Granny Anthony Horowitz Holes Louis Sacher Illegal Eoin Colfer In Your Dreams Isaac Mike Lefroy Journey to the River Sea Eva Ibbotson Krindlekrax Philip Ridley Lion Boy Zizou Corder Lone Wolf Kristine Franklin Macbeth Leon Garfield Maphead Lesley Howarth Maphead 2 Lesley Howarth Midsummer Night's Dream Leon Garfield Millions Frank Cottrell Boyce Mr. William Shakepeare's Plays Marcia Williams My Life as a Movie Hero Eric Johns My Swordhand is Singing Marcus Sedgwick Northern Lights Philip Pullman Once Morris Gleitzman Oranges in No Man's Land Elizabeth Laird Orchard Treasury of Classic Poetry Orchard Raspberries on the Yangtze Karen Wallace Riding the Waves Theresa Tomlinson SeaBEAN Sarah Holding Shakespeare Stories Leon Garfield Silverfin Charlie Higson Something Rare and Special Judy Allen Story of Tracy Beaker Jacqueline Wilson Tell Me No Lies Malorie Blackman The Borrowers Mary Norton The Breadwinner Deborah Ellis The Crowstarver Dick King-Smith The Devil and his Boy Anthony Horowitz The Drowners Garry Douglas Kilworth The Falcon's Malteser Anthony Horowitz The Firework-maker's Daughter Philip Pullman The Girl of Ink and Stars Kiran Millwood Hargrave The Hobbit JRR Tolkein The House of Rats Stephen Elboz The Kite Place J. -

Jacqueline Wilson Biography

Jacqueline Wilson Early life Jacqueline Aitken (she became Wilson when she got married) was born in the city of Bath, in England, on 17th December 1945. Jacqueline’s parents met at a dance in a famous old building in bath called the Pump Room. Her mother was doing office work for the navy and her father was a draughtsman. This was a job which involved drawing skilful plans of machinery and buildings. When Jacqueline was about three years old, her father changed jobs and took the family to live in Kingston upon Thames, near London. For a while they shared their house with Jacqueline’s grandparents who lived downstairs. Jacqueline and her mother and father soon moved to a council flat and Jacqueline started school in 1950. She had a difficult time at first because she fell ill with measles and whooping cough and had to have several months off school. School and Education When she was six she moved to a school called Latchmere Primary and soon settled in. Jacqueline loved English, Art, country dancing and listening to stories. When she was eight, Jacqueline’s mother brought her a very realistic toy dog as Jacqueline longed to have a pet. From the age of seven, Jacqueline loved making up her own stories. She copied out drawings into a blank notebook and invented stories to go with her pictures. When Jacqueline was eleven, she went to a brand new girls’ secondary school in New Malden called Coombe School. She passed her eleven plus and took English, Art and History at school. -

TLG to Big Reading

The Little Guide to Big Reading Talking BBC Big Read books with family, friends and colleagues Contents Introduction page 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group page 4 Book groups at work page 7 Some ideas on what to talk about in your group page 9 The Top 21 page 10 The Top 100 page 20 Other ways to share BBC Big Read books page 26 What next? page 27 The Little Guide to Big Reading was created in collaboration with Booktrust 2 Introduction “I’ve voted for my best-loved book – what do I do now?” The BBC Big Read started with an open invitation for everyone to nominate a favourite book resulting in a list of the nation’s Top 100 books.It will finish by focusing on just 21 novels which matter to millions and give you the chance to vote for your favourite and decide the title of the nation’s best-loved book. This guide provides some ideas on ways to approach The Big Read and advice on: • setting up a Big Read book group • what to talk about and how to structure your meetings • finding other ways to share Big Read books Whether you’re reading by yourself or planning to start a reading group, you can plan your reading around The BBC Big Read and join the nation’s biggest ever book club! 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group “Ours is a social group, really. I sometimes think the book’s just an extra excuse for us to get together once a month.” “I’ve learnt such a lot about literature from the people there.And I’ve read books I’d never have chosen for myself – a real consciousness raiser.” “I’m reading all the time now – and I’m not a reader.” Book groups can be very enjoyable and stimulating.There are tens of thousands of them in existence in the UK and each one is different. -

Jacqueline Wilson Biography

Jacqueline Wilson Biography Jacqueline Aitken (she became Wilson when she got married) was born in the city of Bath, in England, on 17th December 1945. Jacqueline’s parents met at a dance in a famous old building in bath called the Pump Room. Her mother was doing office work for the navy and her father was a draughtsman. This was a job which involved drawing skilful plans of machinery and buildings. When Jacqueline was about three years old, her father changed jobs and took the family to live in Kingston upon Thames, near London. For a while they shared their house with Jacqueline’s grandparents who lived downstairs. Jacqueline and her mother and father soon moved to a council flat and Jacqueline started school in 1950. She had a difficult time at first because she fell ill with measles and whooping cough and had to have several months off school. When she was six she moved to a school called Latchmere Primary and soon settled in. Jacqueline loved English, Art, country dancing and listening to stories. When she was eight, Jacqueline’s mother brought her a very realistic toy dog as Jacqueline longed to have a pet. From the age of seven, Jacqueline loved making up her own stories. She copied out drawings into a blank notebook and invented stories to go with her pictures. When Jacqueline was eleven, she went to a brand new girls’ secondary school in New Malden called Coombe School. She passed her eleven plus and took English, Art and History at school. At the age of sixteen, Jacqueline took her O- Levels. -

Good Books for Tough Times 9-12

Foreword by Michael Morpurgo Good Books for Tough Times Books for children aged 9-12 PARTNERSHIP FOR Good mental health for children - for life Good Books for Tough Times 9-12 Books for children aged 9-12 Edited by Caroline Egar Books selected and reviewed by Caroline Egar and Chris Bale Partnership for Children PARTNERSHIP FOR Good mental health for children - for life 26-27 Market Place Kingston upon Thames Surrey KT1 1JH Tel: 020 8974 6004 email: [email protected] www.partnershipforchildren.org.uk Registered in England and Wales No. 4278914 Registered charity number: 1089810 Published by Partnership for Children Designed by Helen Danby, Partnership for Children Printed by Principal Colour, Paddock Wood, Kent TN12 6DQ Cover photo by Helen Danby © Partnership for Children 2011 ISBN 978-0-9559255-28 FOREWORD Good Books for Tough Times 9-12 1 Foreword by Michael Morpurgo Children’s Laureate 2003-2005 Many years ago I was a school teacher The worst thing to do is to treat with a class of 35 children, all very children as if they’re stupid or don’t different, all with their own likes and understand; they do understand, they dislikes. The one thing they all enjoyed know what the deal is, and books can was the time at the end of the day help them to deal with anxiety and give when they sat on the floor and I told them a sense of perspective. them a story. Within ten seconds, every one of them was interested and That is why Good Books for Tough paying attention. -

Welcome to Bradford Literature Festival's

WELCOME TO BRADFORD LITERATURE FESTIVAL’S 10 Books that Changed My Life with JACQUELINE WILSON Age: This is most suitable for UKS2 (aged 9-11) and KS3 (11-14). National Curriculum links: English, Art Supported by CONTENTS The Teaching grid for UKS2 & KS3 can be found on p. 3 Teacher resources can be found on p. 6 2. UKS2 & KS3 ACTIVITY SUGGESTIONS English English Curriculum Organise their ideas effectively for writing. Identify the audience for and purpose of the writing Recommend books that they have read to their peers, giving reasons for their choices. Learn the conventions of different types of writing, such as the use of the third person in biographies. Teaching Objectives Write a Book Review of a Jacqueline Wilson Book. Write a biography of Jacqueline Wilson Other Curriculum areas Art & Design: Produce creative work, exploring their ideas and recording their experiences Evaluate and analyse creative works using the language of art, craft and design Teaching Objectives Draw a character from one of Jacqueline Wilson’s books. A. PRE-EVENT SUGGESTIONS 1. Our Favourite Books by Jacqueline Wilson Gather children together and ask them if they have read any books by Jacqueline Wilson. o Which books did they like the best? o What sort of books were they? . Were they funny books? . Books to do with friendship? . Books to do with family? . Books to do with relationships? . Books set in the past? . Retelling an old story in a new way? o What was the genre of the book/s? Were they: . Fantasy? . Horror? . Romance? . Science Fiction? . Crime and Mystery? . -

Jacqueline Wilson Chatterbooks Activity Pack

Jacqueline Wilson Chatterbooks activity pack Celebrating the publication of her 100th book Opal Plumstead also featuring her other historical novels – the Hetty Feather adventures About this pack This Chatterbooks pack celebrates the publication of Dame Jacqueline Wilson’s 100th book Opal Plumstead – coming out in October 2014. It’s a historical novel set in 1914, with a feisty Jacqueline Wilson heroine who has to leave school and work in a factory. Opal learns to make her way, meets with suffragettes – and falls in love. Jacqueline Wilson has written four other historical novels, featuring another brave and bright girl, Hetty Feather, who was abandoned as a baby and taken to the Foundling Hospital. In this pack you’ll find lots of information about these books, and about Jacqueline. There are links to Jacqueline’s website www.jacquelinewilson.co.uk and to activity ideas produced by Random House to support a recent ‘virtually live’ session with Jacqueline. And there are more great activities for your group to enjoy, plus ideas for discussion topics, details of more books by Jacqueline, and suggestions for more books to read, linked to the themes in this book. The pack is brought to you by The Reading Agency and their publisher partnership Children’s Reading Partners Chatterbooks is the UK’s largest network of children’s reading groups - for children and young paople aged 4 to 14 years. It is coordinated by The Reading Agency and its patron is author Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Chatterbooks groups run in libraries and schools, supporting and inspiring children’s literacy development by encouraging them to have a really good time reading and talking about books. -

Girl in Progress: Navigating the Mortal Coils of Growing up in the Fiction of Jacqueline Wilson

Girl in Progress: Navigating the Mortal Coils of Growing Up in the Fiction of Jacqueline Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English at the University of Canterbury by Cherilyn Nicole Clark University of Canterbury 2016 For my grandmother, Isla Clark, who was always disappointed if I was not reading a book Table of Contents Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 2 Introduction Adult Ideologies, Postmodern Children, and Jacqueline Wilson 3 Chapter 1 The Dual Wound: Psychological Trauma, and Physical Harm in Falling Apart 9 Chapter 2 The Pressures of a Girl Body: Culture, Body Image, and Food in Girls Under Pressure 38 Chapter 3 Domestic Madness: Home, Family, and Mental Illness in The Illustrated Mum 68 Coda Defining the Voice in Jacqueline Wilson’s Work 99 Works Consulted 103 1 Acknowledgements Many thanks to my academic supervisors, Anna Smith and Annie Potts, for their much appreciated support, feedback, and recommendations while writing this thesis. Thanks to the University of Canterbury Library and the Interloans team in particular for getting much needed research materials to me so quickly. Thank you to my parents, Karen and Pete, and my partner, Ben, for their love and support throughout my studies and for putting up with me when I was at my most stressed. And I won’t forget my friends for sharing cake and conversation with me. Thank you for the distraction. 2 Abstract The following presents a discussion of the work of children’s and young adult novelist, Jacqueline Wilson. My focus is on Wilson’s treatment of issues that are quite pertinent to growing up and growing up as a girl in particular. -

The English Classroom

The English Classroom – a Place of Struggle AN ANALYSIS OF THE POTENTIAL OF CONTEMPORARY YOUNG ADULT FICTION AS A TEACHING TOOL FOR THE ENCOURAGEMENT OF INTERCULTURAL COMPETENCE Heidi Beate Kristensen Master’s thesis Trondheim, May 2015 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Program for Teacher Education Academic supervisors: Anja Synnøve Bakken and Gweno Williams Acknowledgements The road leading up to the result that you are now holding in your hands has been the biggest ‘place of struggle’ that I have ever encountered – and I have been to some pretty desolate and overcrowded places. However, as these journeys usually are, it has been a fruitful road to travel, and for that, there are a few people that need to be acknowledged and thanked. My supervisors, Anja Synnøve Bakken and Gweno Williams, deserve sincere thanks for their honest input and constructive feedback. Mamma and pappa have at times been annoyingly supportive – believing in me unconditionally. The motto has been: Don’t give up! And it worked. Their support has been invaluable, and for that they can take some of the credit for the finished product. Then there are the girls up on the fourth floor. By now they know me better than most. We have shared frustrations, anger, tears, joy, laughter, insights and other confession that had nothing to with culture, novels, analysis or writing. They kept me sane and made the experience enjoyable – new friends were made. Trondheim, May 21, 2015 Heidi Beate Kristensen I Abstract The topic of this thesis investigates the potential of contemporary young adult fiction as a teaching tool for the encouragement of intercultural competence. -

Childlike Parents in Guus Kuijer's Polleke Series and Jacqueline

Childlike Parents in Guus Kuijer’s Polleke Series and Jacqueline Wilson’s The Illustrated Mum Vanessa Joosen INTRODUCTION With its roots in education, children’s literature is an ideological discourse that relies on age for its definition and characterization.1 The role of the adult in the production process of children’s books has been widely studied, as has the construction of childhood in this kind of lit- erature.2 In contrast, the age norms governing the construction of adult- hood in children’s books have received relatively little scholarly attention (Joosen, “Second Childhoods”). This lack of attention can be explained by the fact that—some exceptions with adult protagonists notwithstand- ing—the majority of children’s books feature adults only as secondary characters that are described from a child’s selective point of view (Niko- lajeva, Character 115). Some family stories form an exception to this con- vention, taking the relationship between child and adult as the central focus and having the child protagonist reflect extensively not only on the adults in their surroundings, but also on the notion of adulthood itself. In The Family in English Children’s Literature, Ann Alston observes that many children’s books since the 1970s have asked the child reader “to sympathize and relate to adults’ problems” (59). In this article, I will analyze the demarcation of childhood and adulthood in two such narra- tives, Guus Kuijer’s Polleke series (1999-2001) and Jacqueline Wilson’s The Illustrated Mum (1999). In my analysis of the construction of adulthood and age norms in these narratives, I will rely on Margaret Gullette’s tenet that age is a cul- tural construct and refer to trends in the contemporary understanding of the life course as identified by two leading sociologists working in age studies: Harry Blatterer and Jeffrey Arnett.