Girl in Progress: Navigating the Mortal Coils of Growing up in the Fiction of Jacqueline Wilson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacqueline Wilson Dream Journal Ebook Free Download

JACQUELINE WILSON DREAM JOURNAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jacqueline Wilson, Nick Sharratt | 240 pages | 03 Jul 2014 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780857534316 | English | London, United Kingdom Jacqueline Wilson Dream Journal PDF Book The three girls have been best friends forever, but now Ellie is convinced she's fat, Nadine wants to be a model, and Magda worries that her appearance is giving guys the wrong idea. Em adores her funny, glamorous dad - who cares if he's not her real father? The Diary of a Young Girl. Lily Alone. I Am Sasha. Have you ever wondered what happened to Tracy Beaker? All rights reserved. This was also the first of her books to be illustrated by Nick Sharratt. See More. Friend Reviews. For me, books like this have to exist so that novels covering the more unusual family or young lives of the time can actually be compared with something. Lucky for Mum, because now she's got the flu, so I've got to mind her - and help with all the babies! Isabella Torres rated it it was amazing Oct 27, Rent a Bridesmaid. Jacqueline Wilson Biscuit Barrel. Abschnitt 8. It was a fascinating book and portions of it made me laugh loudly. Log In. The Worry Website. You have no items in your shopping cart. My Secret Diary: Dating, Dancing, Dreams and Dilemmas Best-loved author Jacqueline Wilson continues the captivating story of her life with this gripping account of her teenage years — school life, first love, friends, family and everything! Beauty and her meek, sweet mother live in uneasy fear of his fierce rages, sparked whenever they break one of his fussy house rules. -

Dustbin Baby Free

FREE DUSTBIN BABY PDF Jacqueline Wilson,Nick Sharratt | 240 pages | 27 Mar 2007 | Random House Children's Publishers UK | 9780552556118 | English | London, United Kingdom Dustbin Baby () directed by Juliet May • Reviews, film + cast • Letterboxd Dustbin Baby helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Dustbin Baby by Jacqueline Wilson. Dustbin Baby by Jacqueline Wilson. April Showers so called because of her birth date, April 1, and her tendency to burst into tears at the drop of a hat was unceremoniously dumped in a Dustbin Baby bin when she was only a few hours old. Her young life has passed by in a blur of ever-changing foster homes but Dustbin Baby she enters her teens she decides it is time to find out the truth about her real family. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published October 1st by Corgi Childrens first published September More Details Original Title. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Dustbin Babyplease sign up. Did April find her mother? Navika This answer contains spoilers… view spoiler [No, she found Frankie and got a phone. Donya Do not think so but I Dustbin Baby read it to know Dustbin Baby happend in the real end. See all 4 questions about Dustbin Baby…. -

National GROSSED-UP

100 MOST BORROWED BOOKS (JULY 2003 – JUNE 2004) National ISBN Title Contributor Publisher 1. 0747551006 Harry Potter and the order of J.K. Rowling Bloomsbury the phoenix Children's 2. 0712670599 The king of torts John Grisham Century 3. 0752851659 Quentin's Maeve B inchy Orion 4. 0007146051 Beachcomber Josephine Cox Harper Collins 5. 0747271550 Jinnie Josephine Cox Headline 6. 0747271569 Bad boy Jack Josephine Cox Headline 7. 0333761359 Blue horizon Wilbur Smith Macmillan 8. 0440862795 The story of Tracy Beaker Jacqueline Wilson: ill by Nick Yearling Sharratt 9. 0712684263 The summons John Grisham Century 10. 0752856561 Lost light Michael Connelly Orion 11. 0747271542 The woman who left Josephine Cox Headline 12. 0747263493 Four blind mice James Patterson Headline 13. 0434010367 Bare bones Kathy Reichs Heinema nn 14. 0571218210 The murder room P.D. James Faber 15. 1405001097 Fox evil Minette Walters Macmillan 16. 0593050088 Dating game Danielle Steel Bantam 17. 0007127170 Bad company Jack Higgins HarperCollins 18. 0007120109 Sharpe's havoc: Richard Bernard Cornwell HarperCollins Sharpe and the campaign in Northern> 19. 0752851101 A question of blood Ian Rankin Orion 20. 0593047087 Answered prayers Danielle Steel Bantam 21. 0747546290 Harry Potter and the prisoner J. K. Rowling Bloomsbury of Azkaban 22. 0552546534 Lizzie Zipmouth Jacqueline Wilson: ill Nick Sharratt Young Corgi 23. 0755300181 The jester James Patterson and Andrew Headline Gross 24. 0002261359 Emma's secret Barbara Taylor Bradford HarperCollins 25. 0440863023 Mum-minder Jacqueline Wilson: + ill Nick Yearling Sharratt 26. 0747271526 Looking back Josephine Cox Headline 27. 0747263507 2nd chance James Patterson with Andrew Headline Gross 28. 0752821415 Chasing the dime Michael Connelly Orion 29. -

Recent Issue-Driven Fiction for Young People

OOK WORLD B Boekwêreld • Ilizwe Leencwadi Recent issue-driven fi ction for young people Compiled by JOHANNA DE BEER Assistant Director: Selection and Acquisitions or an introduction to this list of realistic novels, written for older children and teenagers, that deal with issues that are there is, amazingly enough, somebody else out there who’s been Fexperienced by and of concern to this specifi c age group, I through exactly the same thing, it’s when you’re in your teenage turned to a very useful guide to teenage literature, The ultimate years. (Fiction can be hugely comforting for this, in a way that all teen book guide edited by Daniel Hahn and Leonie Flynn (Black, the self-help books in the world, for all their practical worthiness, 2006). This guide is a most useful resource for any teacher or simply cannot)… whatever your own experience it’s somehow librarian working with young people, and indeed young people enormously soothing to read a book that strikes a chord, that themselves, with annotations to over 700 titles suitable for makes you break off in the middle of a sentence and stare into the teenagers and suggestions for further reads if one has enjoyed a middle distance and nod and think: ‘Yes, that’s just how it feels’. specifi c title. Added extras include top ten lists culled from polling (p. 168.) teen readers themselves with the Harry Potter-series topping several Kevin Brooks is one author who does not shy away from the lists from the Book-that-changed-your-life to the Book-you-couldn’t grim reality and harsh challenges facing some young people. -

GARY PARKER Writer

GARY PARKER Writer 2021 OPAL MOONBABY TV adaptation of series of children’s books by Maudie Smith in development 2020-21 FLATMATES (SERIES 2) Lead writer and writer of 3 x episodes Produced by Zodiak for BBC 2020 EJ12 – GIRL HERO Pilot script in development with Ambience Entertainment 2019 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SPECIALS) Wrote 2 x special episodes Produced by Zodiak for CBBC 2017-18 MILLE INBETWEEN (SERIES 4) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 4 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2016 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SERIES 3) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 4 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2015 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SERIES 2) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 5 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2013-14 MILLIE INBETWEEN (SERIES 1) Co-creator and writer of series for CBBC Wrote 7 x episodes, showrunner of entire series Produced by The Foundation 2013 DANI’S CASTLE 2 episodes for RDF Television/Foundation TV 2012 JILLY COOPER ADAPTATION 100 minute TV film adaptation of a Jilly Cooper novel Cooperworld (Neil Zeiger / Greg Boardman) 2010-12 DANI’S HOUSE 7 episodes for RDF Television/Foundation TV 2011 CAMPUS Wrote Pilot and Series 1. Moniker Pictures/Channel 4 DELIVERANCE Team writing for 60 minute comedy drama and series for Company/Channel 4 BEN & HOLLY’S LITTLE KINGDOM 10 x 11 minute scripts for Elf Factory/Nick Jnr and Five Milkshake 2010 FREAKY FARLEYS 3 x 22 minute script for RDF Television/Foundation TV TATI’S HOTEL 2 x 11 minute script for Machine Productions 2009 MUDDLE EARTH 2 x 11 minute animated script for CBBC DANI’S HOUSE 3 x 22 minute script for RDF Television/Foundation TV MYTHS REWIRED 6 x 1 hour series in development with Lime Pictures MIRROR MIRROR 1 x 30 minute episode for BBC3 CAMPUS Pilot for Moniker Pictures Ltd/Channel 4 GASPARD ET LISA Two episodes for Chorion UK 2008 SCHOOL OF COMEDY Sketches for Series, Leftbank/Channel 4. -

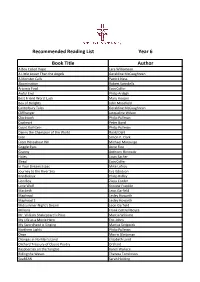

Recommended Reading List Year 6 Book Title Author

Recommended Reading List Year 6 Book Title Author A Boy Called Hope Lara Williamson A Little Lower Than the Angels Geraldine McCaughrean A Monster Calls Patrick Ness Abomination Robert Swindells Artemis Fowl Eoin Colfer Awful End Philip Ardagh Best Friend Worst Luck Mary Hooper Box of Delights John Masefield Canterbury Tales Geraldine McCaughrean Cliffhanger Jacqueline Wilson Clockwork Philip Pullman Cogheart Peter Bunzl Count Karlstein Philip Pullman Danny the Champion of the World Roald Dahl Eren Simon P. Clark From Hereabout Hill Michael Morpurgo Goggle Eyes Anne Fine Granny Anthony Horowitz Holes Louis Sacher Illegal Eoin Colfer In Your Dreams Isaac Mike Lefroy Journey to the River Sea Eva Ibbotson Krindlekrax Philip Ridley Lion Boy Zizou Corder Lone Wolf Kristine Franklin Macbeth Leon Garfield Maphead Lesley Howarth Maphead 2 Lesley Howarth Midsummer Night's Dream Leon Garfield Millions Frank Cottrell Boyce Mr. William Shakepeare's Plays Marcia Williams My Life as a Movie Hero Eric Johns My Swordhand is Singing Marcus Sedgwick Northern Lights Philip Pullman Once Morris Gleitzman Oranges in No Man's Land Elizabeth Laird Orchard Treasury of Classic Poetry Orchard Raspberries on the Yangtze Karen Wallace Riding the Waves Theresa Tomlinson SeaBEAN Sarah Holding Shakespeare Stories Leon Garfield Silverfin Charlie Higson Something Rare and Special Judy Allen Story of Tracy Beaker Jacqueline Wilson Tell Me No Lies Malorie Blackman The Borrowers Mary Norton The Breadwinner Deborah Ellis The Crowstarver Dick King-Smith The Devil and his Boy Anthony Horowitz The Drowners Garry Douglas Kilworth The Falcon's Malteser Anthony Horowitz The Firework-maker's Daughter Philip Pullman The Girl of Ink and Stars Kiran Millwood Hargrave The Hobbit JRR Tolkein The House of Rats Stephen Elboz The Kite Place J. -

Jacqueline Wilson Biography

Jacqueline Wilson Early life Jacqueline Aitken (she became Wilson when she got married) was born in the city of Bath, in England, on 17th December 1945. Jacqueline’s parents met at a dance in a famous old building in bath called the Pump Room. Her mother was doing office work for the navy and her father was a draughtsman. This was a job which involved drawing skilful plans of machinery and buildings. When Jacqueline was about three years old, her father changed jobs and took the family to live in Kingston upon Thames, near London. For a while they shared their house with Jacqueline’s grandparents who lived downstairs. Jacqueline and her mother and father soon moved to a council flat and Jacqueline started school in 1950. She had a difficult time at first because she fell ill with measles and whooping cough and had to have several months off school. School and Education When she was six she moved to a school called Latchmere Primary and soon settled in. Jacqueline loved English, Art, country dancing and listening to stories. When she was eight, Jacqueline’s mother brought her a very realistic toy dog as Jacqueline longed to have a pet. From the age of seven, Jacqueline loved making up her own stories. She copied out drawings into a blank notebook and invented stories to go with her pictures. When Jacqueline was eleven, she went to a brand new girls’ secondary school in New Malden called Coombe School. She passed her eleven plus and took English, Art and History at school. -

TLG to Big Reading

The Little Guide to Big Reading Talking BBC Big Read books with family, friends and colleagues Contents Introduction page 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group page 4 Book groups at work page 7 Some ideas on what to talk about in your group page 9 The Top 21 page 10 The Top 100 page 20 Other ways to share BBC Big Read books page 26 What next? page 27 The Little Guide to Big Reading was created in collaboration with Booktrust 2 Introduction “I’ve voted for my best-loved book – what do I do now?” The BBC Big Read started with an open invitation for everyone to nominate a favourite book resulting in a list of the nation’s Top 100 books.It will finish by focusing on just 21 novels which matter to millions and give you the chance to vote for your favourite and decide the title of the nation’s best-loved book. This guide provides some ideas on ways to approach The Big Read and advice on: • setting up a Big Read book group • what to talk about and how to structure your meetings • finding other ways to share Big Read books Whether you’re reading by yourself or planning to start a reading group, you can plan your reading around The BBC Big Read and join the nation’s biggest ever book club! 3 Setting up your own BBC Big Read book group “Ours is a social group, really. I sometimes think the book’s just an extra excuse for us to get together once a month.” “I’ve learnt such a lot about literature from the people there.And I’ve read books I’d never have chosen for myself – a real consciousness raiser.” “I’m reading all the time now – and I’m not a reader.” Book groups can be very enjoyable and stimulating.There are tens of thousands of them in existence in the UK and each one is different. -

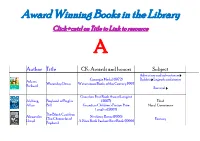

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+Cntrl on Title to Link to Resource A

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+cntrl on Title to Link to resource A Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Adventure and adventurers › Carnegie Medal (1972) Rabbits › Legends and stories Adams, Watership Down Waterstones Books of the Century 1997 Richard Survival › Guardian First Book Award Longlist Ahlberg, Boyhood of Buglar (2007) Thief Allan Bill Guardian Children's Fiction Prize Moral Conscience Longlist (2007) The Black Cauldron Alexander, Newbery Honor (1966) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1966) Prydain) Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject The Book of Three Alexander, A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1965) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd Prydain Book 1) A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1967) Alexander, Castle of Llyr Fantasy Lloyd Princesses › A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1968) Taran Wanderer (The Alexander, Fairy tales Chronicles of Lloyd Fantasy Prydain) Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2003) Whitbread (Children's Book, 2003) Boston Globe–Horn Book Award Almond, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 › The Fire-eaters (Fiction, 2004) David Great Britain › History Nestlé Smarties Book Prize (Gold Award, 9-11 years category, 2003) Whitbread Shortlist (Children's Book, Adventure and adventurers › Almond, 2000) Heaven Eyes Orphans › David Zilveren Zoen (2002) Runaway children › Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2000) Amateau, Chancey of the SIBA Book Award Nominee courage, Gigi Maury River Perseverance Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Angeli, Newbery Medal (1950) Great Britain › Fiction. › Edward III, Marguerite The Door in the Wall Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1961) 1327-1377 De A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1950) Physically handicapped › Armstrong, Newbery Honor (2006) Whittington Cats › Alan Newbery Honor (1939) Humorous stories Atwater, Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1958) Mr. -

Year 5 Reading Leaflet

Research has shown that children who read regularly, and are frequently read to, will make significantly more progress than those who do not. We want all of our children to love reading and to read for pleasure. Reading with your child for as little as 10 minutes every day can make an enormous difference and, is there anything nicer than snuggling up with your child to enjoy a great story? Throughout the year we will be planning a range of exciting activities to promote reading. We are also very pleased to announce that we will have two Reading Champions this year! Our link with the poet Paul Cookson will continue and he will again be a regular feature in school. Alongside Paul as Reading Champion this year, we have Tom Palmer who will also be launching our World Cup topic in the summer. We are also pleased to have the fantastic Simon Bartram visiting Key stage 1 this November. In this booklet you will find lots of information and tip tips to help you support your child with their reading. We have included some suggestions of our favourite books from Year 5 over the next few pages and there are some fantastic reads on the list! So, when you can find a minute, pick one and enjoy it with them. Enjoy the information enclosed and thank you for your continued support. Happy reading Mr Hall Assistant Head/English Lead This year we have begun a project to increase our focus in supporting and developing children’s speaking and listening skills. -

Jacqueline Wilson Biography

Jacqueline Wilson Biography Jacqueline Aitken (she became Wilson when she got married) was born in the city of Bath, in England, on 17th December 1945. Jacqueline’s parents met at a dance in a famous old building in bath called the Pump Room. Her mother was doing office work for the navy and her father was a draughtsman. This was a job which involved drawing skilful plans of machinery and buildings. When Jacqueline was about three years old, her father changed jobs and took the family to live in Kingston upon Thames, near London. For a while they shared their house with Jacqueline’s grandparents who lived downstairs. Jacqueline and her mother and father soon moved to a council flat and Jacqueline started school in 1950. She had a difficult time at first because she fell ill with measles and whooping cough and had to have several months off school. When she was six she moved to a school called Latchmere Primary and soon settled in. Jacqueline loved English, Art, country dancing and listening to stories. When she was eight, Jacqueline’s mother brought her a very realistic toy dog as Jacqueline longed to have a pet. From the age of seven, Jacqueline loved making up her own stories. She copied out drawings into a blank notebook and invented stories to go with her pictures. When Jacqueline was eleven, she went to a brand new girls’ secondary school in New Malden called Coombe School. She passed her eleven plus and took English, Art and History at school. At the age of sixteen, Jacqueline took her O- Levels. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays.