1 CONTENTS What Is a Grass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Types of American Grasses

z LIBRARY OF Si AS-HITCHCOCK AND AGNES'CHASE 4: SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM oL TiiC. CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE United States National Herbarium Volume XII, Part 3 TXE&3 OF AMERICAN GRASSES . / A STUDY OF THE AMERICAN SPECIES OF GRASSES DESCRIBED BY LINNAEUS, GRONOVIUS, SLOANE, SWARTZ, AND MICHAUX By A. S. HITCHCOCK z rit erV ^-C?^ 1 " WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1908 BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Issued June 18, 1908 ii PREFACE The accompanying paper, by Prof. A. S. Hitchcock, Systematic Agrostologist of the United States Department of Agriculture, u entitled Types of American grasses: a study of the American species of grasses described by Linnaeus, Gronovius, Sloane, Swartz, and Michaux," is an important contribution to our knowledge of American grasses. It is regarded as of fundamental importance in the critical sys- tematic investigation of any group of plants that the identity of the species described by earlier authors be determined with certainty. Often this identification can be made only by examining the type specimen, the original description being inconclusive. Under the American code of botanical nomenclature, which has been followed by the author of this paper, "the nomenclatorial t}rpe of a species or subspecies is the specimen to which the describer originally applied the name in publication." The procedure indicated by the American code, namely, to appeal to the type specimen when the original description is insufficient to identify the species, has been much misunderstood by European botanists. It has been taken to mean, in the case of the Linnsean herbarium, for example, that a specimen in that herbarium bearing the same name as a species described by Linnaeus in his Species Plantarum must be taken as the type of that species regardless of all other considerations. -

Grass Genera in Townsville

Grass Genera in Townsville Nanette B. Hooker Photographs by Chris Gardiner SCHOOL OF MARINE and TROPICAL BIOLOGY JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY TOWNSVILLE QUEENSLAND James Cook University 2012 GRASSES OF THE TOWNSVILLE AREA Welcome to the grasses of the Townsville area. The genera covered in this treatment are those found in the lowland areas around Townsville as far north as Bluewater, south to Alligator Creek and west to the base of Hervey’s Range. Most of these genera will also be found in neighbouring areas although some genera not included may occur in specific habitats. The aim of this book is to provide a description of the grass genera as well as a list of species. The grasses belong to a very widespread and large family called the Poaceae. The original family name Gramineae is used in some publications, in Australia the preferred family name is Poaceae. It is one of the largest flowering plant families of the world, comprising more than 700 genera, and more than 10,000 species. In Australia there are over 1300 species including non-native grasses. In the Townsville area there are more than 220 grass species. The grasses have highly modified flowers arranged in a variety of ways. Because they are highly modified and specialized, there are also many new terms used to describe the various features. Hence there is a lot of terminology that chiefly applies to grasses, but some terms are used also in the sedge family. The basic unit of the grass inflorescence (The flowering part) is the spikelet. The spikelet consists of 1-2 basal glumes (bracts at the base) that subtend 1-many florets or flowers. -

Wild Plants of Big Break Regional Shoreline Common Name Version

Wild Plants of Big Break Regional Shoreline Common Name Version A Photographic Guide Sorted by Form, Color and Family with Habitat Descriptions and Identification Notes Photographs and text by Wilde Legard District Botanist, East Bay Regional Park District New Revised and Expanded Edition - Includes the latest scientific names, habitat descriptions and identification notes Decimal Inches .1 .2 .3 .4 .5 .6 .7 .8 .9 1 .5 2 .5 3 .5 4 .5 5 .5 6 .5 7 .5 8 .5 9 1/8 1/4 1/2 3/4 1 1/2 2 1/2 3 1/2 4 1/2 5 1/2 6 1/2 7 1/2 8 1/2 9 English Inches Notes: A Photographic Guide to the Wild Plants of Big Break Regional Shoreline More than 2,000 species of native and naturalized plants grow wild in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most are very difficult to identify without the help of good illustrations. This is designed to be a simple, color photo guide to help you identify some of these plants. This guide is published electronically in Adobe Acrobat® format so that it can easily be updated as additional photographs become available. You have permission to freely download, distribute and print this guide for individual use. Photographs are © 2014 Wilde Legard, all rights reserved. In this guide, the included plants are sorted first by form (Ferns & Fern-like, Grasses & Grass-like, Herbaceous, Woody), then by most common flower color, and finally by similar looking flowers (grouped by genus within each family). Each photograph has the following information, separated by '-': COMMON NAME According to The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition (JM2) and other references (not standardized). -

Ajo Peak to Tinajas Altas: a Flora of Southwestern Arizona

Felger, R.S., S. Rutman, and J. Malusa. 2014. Ajo Peak to Tinajas Altas: A flora of southwestern Arizona. Part 6. Poaceae – grass family. Phytoneuron 2014-35: 1–139. Published 17 March 2014. ISSN 2153 733X AJO PEAK TO TINAJAS ALTAS: A FLORA OF SOUTHWESTERN ARIZONA Part 6. POACEAE – GRASS FAMILY RICHARD STEPHEN FELGER Herbarium, University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 & Sky Island Alliance P.O. Box 41165, Tucson, Arizona 85717 *Author for correspondence: [email protected] SUSAN RUTMAN 90 West 10th Street Ajo, Arizona 85321 JIM MALUSA School of Natural Resources and the Environment University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 [email protected] ABSTRACT A floristic account is provided for the grass family as part of the vascular plant flora of the contiguous protected areas of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and the Tinajas Altas Region in southwestern Arizona. This is the second largest family in the flora area after Asteraceae. A total of 97 taxa in 46 genera of grasses are included in this publication, which includes ones established and reproducing in the modern flora (86 taxa in 43 genera), some occurring at the margins of the flora area or no long known from the area, and ice age fossils. At least 28 taxa are known by fossils recovered from packrat middens, five of which have not been found in the modern flora: little barley ( Hordeum pusillum ), cliff muhly ( Muhlenbergia polycaulis ), Paspalum sp., mutton bluegrass ( Poa fendleriana ), and bulb panic grass ( Zuloagaea bulbosa ). Non-native grasses are represented by 27 species, or 28% of the modern grass flora. -

Plant Associations and Descriptions for American Memorial Park, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Saipan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Vegetation Inventory Project American Memorial Park Natural Resource Report NPS/PACN/NRR—2013/744 ON THE COVER Coastal shoreline at American Memorial Park Photograph by: David Benitez Vegetation Inventory Project American Memorial Park Natural Resource Report NPS/PACN/NRR—2013/744 Dan Cogan1, Gwen Kittel2, Meagan Selvig3, Alison Ainsworth4, David Benitez5 1Cogan Technology, Inc. 21 Valley Road Galena, IL 61036 2NatureServe 2108 55th Street, Suite 220 Boulder, CO 80301 3Hawaii-Pacific Islands Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (HPI-CESU) University of Hawaii at Hilo 200 W. Kawili St. Hilo, HI 96720 4National Park Service Pacific Island Network – Inventory and Monitoring PO Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 5National Park Service Hawaii Volcanoes National Park – Resources Management PO Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 December 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

A New Species of Bothriochloa (Poaceae, Andropogoneae) Endemic to Montane Grasslands of Santa Catarina, Brazil

Phytotaxa 183 (1): 044–050 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.183.1.5 A new species of Bothriochloa (Poaceae, Andropogoneae) endemic to montane grasslands of Santa Catarina, Brazil 1 1 EMILAINE BIAVA DALMOLIM & ANA ZANIN 1 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia de Fungos, Algas e Plantas, Departamento de Botânica, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Campus Trindade, 88040-900, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Email: [email protected] Abstract Bothriochloa catharinensis, a new species of Andropogoneae (Poaceae: Panicoideae, Andropogoneae) endemic to mon- tane grasslands associated with araucaria forest in the state of Santa Catarina, Southern Brazil, is described and illustrated. Morphological similarities between the new taxon and other species of Bothriochloa are discussed. Comments on habitat, morphology, distribution and conservation status are provided. Key words: araucaria forest, grasses, Panicoideae, SEM, taxonomy Resumo Bothriochloa catharinensis, uma nova espécie de Poaceae considerada endêmica de campos de altitude associados à Floresta Ombró- fila Mista (floresta com araucária) do Estado de Santa Catarina, Sul do Brasil, é aqui descrita e ilustrada. Similaridades morfológicas entre a nova espécie e outros táxons de Bothriochloa são discutidas. São fornecidos dados sobre hábitat, morfologia, distribuição e estado de conservação. Palavras chave: Floresta Ombrófila Mista, gramíneas, MEV, Panicoideae, taxonomia Introduction Bothriochloa Kuntze (1891: 762) comprises about 40 species distributed largely in warm-temperate areas of the world (Scrivanti et al. 2009). In the Americas, the genus is represented by about 27 species widely distributed in tropical, temperate and subtropical regions; four of these have been cultivated and naturalized (Vega 2000, Vega & Scrivanti 2012). -

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(S): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P

Phylogeny and Subfamilial Classification of the Grasses (Poaceae) Author(s): Grass Phylogeny Working Group, Nigel P. Barker, Lynn G. Clark, Jerrold I. Davis, Melvin R. Duvall, Gerald F. Guala, Catherine Hsiao, Elizabeth A. Kellogg, H. Peter Linder Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, Vol. 88, No. 3 (Summer, 2001), pp. 373-457 Published by: Missouri Botanical Garden Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3298585 Accessed: 06/10/2008 11:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mobot. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q a Records

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q A Records plants monocots Poaceae Paspalidium rarum C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida latifolia feathertop wiregrass C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida lazaridis C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Astrebla pectinata barley mitchell grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus setigerus Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Echinochloa colona awnless barnyard grass Y 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida polyclados C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cymbopogon ambiguus lemon grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria ctenantha C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enteropogon ramosus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon avenaceus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eragrostis tenellula delicate lovegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Urochloa praetervisa C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Heteropogon contortus black speargrass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Iseilema membranaceum small flinders grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Bothriochloa ewartiana desert bluegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Brachyachne convergens common native couch C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon lindleyanus C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon polyphyllus leafy nineawn C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus actinocladus katoora grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus pennisetiformis Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus australasicus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne pulchella subsp. dominii C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Dichanthium sericeum subsp. humilius C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria divaricatissima var. divaricatissima C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne mucronata forma (Alpha C.E.Hubbard 7882) C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sehima nervosum C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eulalia aurea silky browntop C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Chloris virgata feathertop rhodes grass Y 1/1 CODES I - Y indicates that the taxon is introduced to Queensland and has naturalised. -

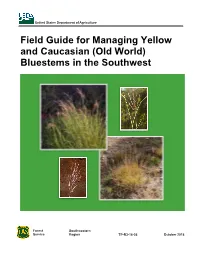

Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest

USDA United States Department of Agriculture - Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest Forest Southwestern Service Region TP-R3-16-36 October 2018 Cover Photos Top left — Yellow bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Top right — Yellow bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Billy Warrick; Soil, Crop and More Information Lower left — Caucasian bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Lower right — Caucasian bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Authors Karen R. Hickman — Professor, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater OK Keith Harmoney — Range Scientist, KSU Ag Research Center, Hays KS Allen White — Region 3 Pesticides/Invasive Species Coord., Forest Service, Albuquerque NM Citation: USDA Forest Service. 2018. Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest. Southwestern Region TP-R3-16-36, Albuquerque, NM. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. -

Viruses and Virus Diseases of Poaceae (Gramineae)

Introduction Hervé Lapierre The Poaceae family comprises a very high number of genera and species. The links between these species and other families are still the subject of many adjustments (see chapter 1). The rapid and continual evolution of our knowledge of biochemical proper- ties and of genomic sequences of the different taxa in this plant family keeps widening perspectives to breeders, agronomists and, of course, to pathologists. The detailed studies of the genetic potential of these species allows us to diversify our strategies in the framework of a sustainable agriculture, particularly concerning the control of viruses that still remains difficult. The globalisation of exchanges of cultivated plants started many thousands years ago and was accelerated with the opening of the oceanic spaces in the XVIth century. The four following centuries have seen the diffusion, all over the world, of the main indus- trial and dietary Poaceae. The beginning of our century seems to have initiated the dif- fusion of ornamental Poaceae and parks. The diffusion of Poaceae species in new ecosystems, and, sometimes in very wide areas as well as the rapid modifications of cultivation methods, inevitably brought about modifications of plant/bio-aggressor balances. The methods for fighting viruses as counterparts to other bio-aggressors still often exploit chemical action against the vectors when the natural resistances are low or non-existent. The use of chemical fight- ing methods against these vectors has become a considerable societal issue as are all the new methods using transgenesis. Many analyses focusing on the challenges linked to transgenesis as a method for fighting the viruses of Poaceae are presented in this book. -

Who's Related to Whom?

149 Who’s related to whom? Recent results from molecular systematic studies Elizabeth A Kellogg Similarities among model systems can lead to generalizations systematist’s question-why are there so many different about plants, but understanding the differences requires kinds of organisms? Studies of the evolution of develop- systematic data. Molecular phylogenetic analyses produce ment demand that the investigator go beyond the model results similar to traditional classifications in the grasses system and learn the pattern of variation in its relatives (Poaceae), and relationships among the cereal crops [3*]. This requires a reasonable assessment of the relatives’ are quite clear. Chloroplast-based phylogenies for the identity. Solanaceae show that tomato is best considered as a species of Solarium, closely related to potatoes. Traditional Knowledge of plant relationships has increased rapidly classifications in the Brassicaceae are misleading with in the past decade, reflecting partly the development regard to true phylogenetic relationships and data are only of molecular systematics. It has been known for some now beginning to clarify the situation. Molecular data are time that plant classifications do not reflect phylogeny also being used to revise our view of relationships among accurately, even though both phylogeny and classification flowering plant families. Phylogenetic data are critical for are hierarchical. The hierarchy of classification was interpreting hypotheses of the evolution of development. imposed in the late 18th century, well before ideas of descent with modification (evolution) were prevalent [4]. These pre-evolutionary groups were then re-interpreted in Address an evolutionary context, and were assumed to be products Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue Cambridge, MA of evolution, rather than man-made artefacts.