Sharing American Values and the Way Ahead for Public Diplomacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Layalina Chronicle / Summer 2008

LAYALINA PRODUCTIONS Quarterly Newsletter / Summer 2008 US Premiere: On the Road in America Spotlight: Honorary Chairman President George H.W. Bush and Layalina President Ambassador Marc Ginsberg On June 9, Layalina’s President Ambassador Marc Ginsberg met with Layalina’s Honorary Chairman, President George H.W. Bush, at the White House. Top left to right: Ambassador Marc Ginsberg, Layalina’s President; Ali Amr, castmember; Ambassador Ginsberg briefed President Bush Lara Abou Saifan, castmember; Pat Mitchell, President and CEO, The Paley Center for Media; Jerome Gary, Executive Producer and Director of On the Road in America; Ambassador Richard Fairbanks, on Layalina’s programming achievements and Founder and Chairman of Layalina. Bottom left to right: Leon Shahabian, Layalina’s Vice President and its future production schedule, including the Executive Producer of On the Road; Laura Michalchyshyn, Sundance Channel’s Executive Vice President; successful airing of On the Road in America in and Larry Aidem, Sundance Channel President and CEO. the Middle East and its debut on the Sundance Channel in the US. On the Road in America, Layalina’s 12-episode reality Viewer feedback travelogue series, had its US premiere broadcast in primetime on both coasts on the Sundance “I am a Jew and a They also discussed current Mideast Channel from June 4 through August 20. supporter of Israel. The developments focusing on Layalina’s public interactions between Lara diplomacy mission in the MENA region and Produced by Layalina in association with [castmember], a Palestinian, the role that private sector initiatives are Visionaire Media of Los Angeles, On the Road and Guy [director of playing in support of such missions. -

Social Media Accountability for Terrorist Propaganda

SOCIAL MEDIA ACCOUNTABILITY FOR TERRORIST PROPAGANDA Alexander Tsesis* Terrorist organizations have found social media websites to be invaluable for disseminating ideology, recruiting terrorists, and planning operations. National and international leaders have repeatedly pointed out the dangers terrorists pose to ordinary people and state institutions. In the United States, the federal Communications Decency Act’s § 230 provides social networking websites with immunity against civil law suits. Litigants have therefore been unsuccessful in obtaining redress against internet companies who host or disseminate third-party terrorist content. This Article demonstrates that § 230 does not bar private parties from recovery if they can prove that a social media company had received complaints about specific webpages, videos, posts, articles, IP addresses, or accounts of foreign terrorist organizations; the company’s failure to remove the material; a terrorist’s subsequent viewing of or interacting with the material on the website; and that terrorist’s acting upon the propaganda to harm the plaintiff. This Article argues that irrespective of civil immunity, the First Amendment does not limit Congress’s authority to impose criminal liability on those content intermediaries who have been notified that their websites are hosting third-party foreign terrorist incitement, recruitment, or instruction. Neither the First Amendment nor the Communications Decency Act prevents this form of federal criminal prosecution. A social media company can be prosecuted for material support of terrorism if it is knowingly providing a platform to organizations or individuals who advocate the commission of terrorist acts. Mechanisms will also need to be created that can enable administrators to take emergency measures, while simultaneously preserving the due process rights of internet intermediaries to challenge orders to immediately block, temporarily remove, or permanently destroy data. -

RAND CP1-2014.Pdf

C O R P O R A T I O N ANNUAL REPORT 2014 48 44 OUTREACH 2014 BY THE NUMBERS 4 RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS 46 50 PEOPLE EVENTS 66 54 ADVISORY BOARDS 70 PARDEE RAND GRADUATE SCHOOL 58 CLIENTS AND GRANTORS INVESTING IN PEOPLE AND IDEAS Nonprofit Nonpartisan Committed to the public interest RAND develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make people throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. @RANDCorporation Message from the Chair and the President In this age of information overload, the challenge for decisionmakers lies in finding information that is useful, timely, and trustworthy. Time and again, they turn to us for guidance, knowing that every undertaking at RAND is founded on a commitment to providing unbiased, uncensored, fact-based research and analysis. Amid 2014’s violence, crises, and political upheaval, experts at RAND looked for solutions to some of the world’s most pressing challenges, including the rise of a powerful terrorist organization in the Middle East, destructive cyberattacks, the growing military caregiver crisis in the United States, and the relentless advance of dementia. They also looked ahead to emerging issues, studying the potential promise and peril of autonomous vehicles, new ways to structure and employ military power, means of curbing runaway health care spending, and how technology use in early childhood education might help level the playing field for disadvantaged children. Of course, these are just a few of the more than 1,700 ongoing research projects at RAND designed to help make people around the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. -

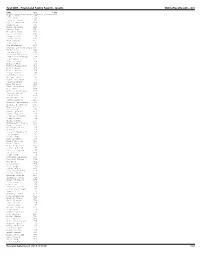

N Ame G En D Er Age C Ity Flat G Et It 5 K B Rain Fitn Ess 5 K Daw So

Name Gender Age City Get Flat It 5K Brain Fitness 5K 5K Dash Dawson 10K Vineyard the to Dash ClassicOld Capitol 5K Points Total DistanceTotal 0-10 Male Jackson Krueger M 8 Dacula 10 518 139.5 Pi Dorminy M 7 Mcdonough 9 160 52.9 Timmy Reed M 6 Crawfordville 105 27.9 Andy Jacoby M 9 Social Circle 58 24.8 Charles Jackson M 10 Tucker 10 56 18.6 Jackson Moss M 8 Covington 52 12.4 Reid Bangle M 10 Athens 50 6.2 Montana Archer M 8 Covington 38 6.2 Jaxon Dean M 9 Covington 38 6.2 Dylan Torrico M 7 Canton 36 6.2 Jackson Yeomans M 8 Covington 36 6.2 Westbrook Adams M 8 Athens 33 6.2 David Duncan Jr M 7 Bogart 32 6.2 Braden Fass M 10 Athens 31 6.2 James Reed M 5 Crawfordville 31 12.4 Chase Stephens M 8 Maysville 29 9.3 Conagher Wheeler M 8 Covington 29 6.2 Tyler Daniels M 9 Woodstock 28 3.1 Blaise Hequembourg M 10 Monticello 27 3.1 Rand Miller M 9 Woodstock 27 3.1 Wallace Morgan M 10 Mansfield 27 6.2 Dean Ryland M 8 Covington 27 3.1 Hank Stephens M 7 Athens 27 6.2 Gabriel Stutz M 10 Athens 27 3.1 Caden English M 10 Canton 26 3.1 Ryan Foster M 10 Athens 26 3.1 Bo Stephens M 8 Athens 26 6.2 Garrett Kennedy M 9 Watkinsville 25 3.1 Robby McGoldrick M 10 Oxford 25 3.1 Will Sumner M 10 Canton 25 3.1 Keegan Baker M 10 Canton 24 3.1 George Barkley Jr M 8 Athens 24 6.2 Brady Williams M 8 Oxford 24 3.1 Steven Blair M 9 Conyers 23 12.4 Knox Gaines M 10 High Shoals 23 12.4 Walter Hequembourg M 8 Monticello 23 3.1 Jojo Palmese M 10 Canton 23 3.1 Lukas Stutz M 8 Athens 23 3.1 Hayden Clark M 10 Canton 22 3.1 Benton Kleiber M 8 Athens 22 6.2 Mason Owens M 9 Mansfield -

Lars Larson to Our Daily Lineup Passionate, Credible and Always a Year Ago

Conservative Talk Radio Journalist Crossing Generations Celebrating over 12 years in National Syndication Ratings dominance on flagship station KXL-FM Portland, OR Consistently ranked by Talkers among the most influential Talk hosts in America Winner of over 75 Journalism Awards 2nd First Immigration Amendment Amendment Fridays Interviews Obamacare Economy Ann Coulter Weekly Apprearance William Shatner - Actor famously known the bestselling book "Case for HuffingtonPost.com as Star Trek's Captain Kirk Democracy" Byron York, National Review Bill Cosby - Actor Kimberly Dozier - CBS News Reporter Bill Kristol, Editor, Weekly Standard Gov. Sarah Palin - Governor of Alaska Newt Gingrich - former Speaker of the Robert Novak - nationally syndicated Rev. Jesse Jackson - Civil Rights Leader House columnist and author of “Prince of Rep. Dennis Kucinich - D-OH James Taranto - columnist, Wall Street Darkness: Fifty Years Reporting in John Stossel - ABC's 20/20 Co-anchor Journal Washington” James Rosen - Fox News Channel's Pat Buchanan - nationally syndicated Andrew McCarthy, National Review Washington Correspondent columnist columnist and senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies Rep. John Boehner - House Republican Mark Steyn - nationally syndicated Leader columnist Greg Gutfeld, host of Fox News Channel's Red Eye Show Richard Perle - one of the architects of Lis Wiehl - legal analyst, Fox News the Iraq War Channel Andrew Breitbart, DrudgeReport.com Amb. Marc Ginsberg - Former Sen. James Inhofe (R-OK), Ranking Kinky Friedman - country music star and Ambassador of Morocco and Fox News Member of the Environment & Public former candidate for Texas governor Channel Foreign Affairs Analyst Works Committee Col. Steven Boylan - Spokesman for Ted Nugent - Country music star General Petraeus Rep. -

Israel Hasbara Committee 01/12/2009 20:53

Israel Hasbara Committee 01/12/2009 20:53 Updated 27 November 2008 Not logged in Please click here to login or register Alphabetical List of Authors (IHC News, 23 Oct. 2007) Aaron Hanscom Aaron Klein Aaron Velasquez Abraham Bell Abraham H. Miller Adam Hanft Addison Gardner ADL Aish.com Staff Akbar Atri Akiva Eldar Alan Dershowitz Alan Edelstein Alan M. Dershowitz Alasdair Palmer Aleksandra Fliegler Alexander Maistrovoy Alex Fishman Alex Grobman Alex Rose Alex Safian, PhD Alireza Jafarzadeh Alistair Lyon Aluf Benn Ambassador Dan Gillerman Ambassador Dan Gillerman, Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations AMCHA American Airlines Pilot - Captain John Maniscalco Amihai Zippor Amihai Zippor. Ami Isseroff Amiram Barkat Amir Taheri Amnon Rubinstein Amos Asa-el Amos Harel Anav Silverman Andrea Sragg Simantov Andre Oboler Andrew Higgins Andrew Roberts Andrew White Anis Shorrosh Anne Bayefsky Anshel Pfeffer Anthony David Marks Anthony David Marks and Hannah Amit AP and Herb Keinon Ari Shavit and Yuval Yoaz Arlene Peck Arnold Reisman Arutz Sheva Asaf Romirowsky Asaf Romirowsky and Jonathan Spyer http://www.infoisrael.net/authors.html Page 1 of 34 Israel Hasbara Committee 01/12/2009 20:53 Assaf Sagiv Associated Press Aviad Rubin Avi Goldreich Avi Jorisch Avraham Diskin Avraham Shmuel Lewin A weekly Torah column from the OU's Torah Tidbits Ayaan Hirsi Ali Azar Majedi B'nai Brith Canada Barak Ravid Barry Rubin Barry Shaw BBC BBC News Ben-Dror Yemini Benjamin Weinthal Benny Avni Benny Morris Berel Wein Bernard Lewis Bet Stephens BICOM Bill Mehlman Bill Oakfield Bob Dylan Bob Unruh Borderfire Report Boris Celser Bradley Burston Bret Stephens BRET STEPHENS Bret Stevens Brian Krebs Britain Israel Communications Research Center (BICOM) British Israel Communications & Research Centre (BICOM) Brooke Goldstein Brooke M. -

The Trinity Reporter, Winter 1984

R E p 0 R T E R WINTER 1984 Mr. Peter J. Knapp 20 Buena Vista Rd. West Hartford, CT 06107 ------ --~--- National Alumni Association EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS President Victor F. Keen '63, New York Senior Vice President James P. Whitters III '62, Boston Vice Presidents Alumni Fund Peter Hoffman '61, New York Campus Activities Jeffrey]. Fox '67, Newington, Ct. Admissions Susan Martin Haberlandt '71, West Hartford Area Associations Merrill A. Yavinsky '65, Washington, D.C. Public Relations Wenda Harris Millard '76, New York Career Counseling Eugene Shen '76, New York Secretary-Treasurer Alfred Steel, Jr. '64, West Hartford MEMBERS B. Graeme Frazier III '53, Philadelphia Megan). O'Neill '73, Bristol, Ct. Charles E. Gooley '75, Hartford James A. Finkelstein '74, La Jolla, Ca. Richard P. Morris '68, Philadelphia Robert N. Hunter '52, Glastonbury, Ct., Ex-Officio Athletic Advisory Committee Term Expires EdwardS. Ludorf'51, Hartford 1984 Donald). Viering '42, Simsbury, Ct. 1984 Susan Martin Haberlandt '71, West Hartford 1985 Alumni Trustees Term Expires Edward A. Montgomery, Jr. '56, Pittsburgh 1984 Emily G. Holcombe '74, Hartford 1985 Marshall E. Blume '63, Villanova, Pa. 1986 New England Champs! Stanley]. Marcuss '63, Washington, D.C. 1987 Donald L. McLagan '64, Lexington, Ma. 1988 As this issue went to press, the T rin David R. Smith '52, Scarborough, ity basketball team had just completed its sweep through the E.C.A.C. New Ontario, Canada 1989 England Division III tournament. The Bantams completely dominated three Nominating Committee Term Expires tournament foes as they thrashed Bab John C. Gunning '49, Hartford 1984 son, 96-72, and Southeastern Mass., Wenda Harris Millard '76, New York 1984 97-69, before a convincing 99-78 vic Norman C. -

Disconnected Narratives Between the United States and Global Muslim Communities

The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World 2011 U.S.-Islamic World Forum Papers Disconnected Narratives between the United States and Global Muslim Communities C o n v e n e d by : Leon Shahabian A u t h o r e d by : Anne Hagood Ambassador Marc Ginsberg the brookings institution 1775 MAssachusetts Ave., nW WAshington, d.C. 20036-2103 at Brookings www.usislamicworldforum.org AUGUST 2011 Disconnected Narratives between the United States and Global Muslim Communities C o n v e n e d by : Leon Shahabian A u t h o r e d by : Anne Hagood Ambassador Marc Ginsberg at Brookings AUGUST 2011 or the first time in its eight-year history, the 2011 U.S.-Islamic World Forum was held in Washington, DC. The Forum, co-convened annually by the Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World and the State of Qatar, once again served as the premier convening body for key Fleaders from government, civil society, academia, business, religious communities, and the media. For three days, Forum participants gathered to discuss some of the most pressing issues facing the relationship between the United States and global Muslim communities. This year, the Forum featured a variety of different platforms for thoughtful discussion and constructive engagement, including televised plenary sessions with STEERING COMMITTEE prominent international figures on broad thematic issues of global importance; smaller roundtable discussions led by experts and policymakers on a particular Stephen R. GRand theme or set of countries; and working groups which brought together practitioners director in a given field several times during the course of the Forum to develop practical project on U.S. -

Interview with the Honorable Robert E. Hunter , 2011

Library of Congress Interview with The Honorable Robert E. Hunter , 2011 The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR ROBERT E. HUNTER Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: August 10, 2004 Copyright 2010 ADST Q: Today is the 10th of August, 2004. This is an interview with Robert Hunter, middle initial? HUNTER: E. Q: What does that stand for? HUNTER: Edwards Q: And I'm Charles Stuart Kennedy and this is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. To begin, when and where were you born? HUNTER: The first of May, 1940 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Q: Can you tell me something about the Hunter family; let's start with the father's side. HUNTER: My father was in business, the family was from Quincy, Massachusetts. He was the first person in the family on that side to go to college, he went to Boston University. Graduated the year the Great Depression began. Of course, that was a generation that was very much affected by the Depression and what happened afterwards. Interview with The Honorable Robert E. Hunter , 2011 http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib001708 Library of Congress Q: Where did the Hunters come from? HUNTER: Mostly Scotland, through Nova Scotia. Some Irish, some English, some French, way back. The first ones that show up, on Ancestry.com, I learned only recently, were in Charleston, Mass. in 1636, but we have no family lore on them - as Horatio said, I “do in part believe it!” I know we had some come from Ireland to Massachusetts in the 1740s, and then the next generation left between 1774 and '81 to go to Nova Scotia, which indicates to me they were probably on the wrong side of the Revolution! About the middle of the nineteenth century, they came back to the Quincy area. -

Friend and Family Search - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

Test 2005 - Friend and Family Search - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Sophie Walker F70 Jill Kohla F46 Diana Bruckner F70 Justin Laughlin M38 Ruifang Li F43 Micah Sterling M26 Gianna Terra F9 Meredith Linde F25 Carter Wilson M9 Karen Vicsik F35 Darin Parks M42 mike webster M37 Jiyu Kim F8 Jed MacArthur M38 Stryder Lafone-Demaroi M8 Ed McDevitt M40 Don McJunkin M68 Kristina Wilcoxson F23 Debbie Eichelberger F35 Jay Tippets M35 Jennifer Hart F39 Angela Upton F31 Autumn Warrington F37 Ashley Henkle F36 Nicole Martin F29 Tracy Hansen F61 Samantha Lucero F44 Whitney Shaw F28 Joanne Sorensen F73 Julia Brabant F32 Lisa Thorson F32 Julia Ostrander F15 Nate Muniz M26 Andreas Muschinski M51 Kathryn Ferrel F19 Jon Collis M39 Marina Griffin F9 Justin Bartsch M13 Kaitlyn Blackburn F14 Charlie Heathwood M9 Wyatt Schroth M12 Helen Wright F73 Ylann goresko M13 Lynne Ferguson F43 Lindsay Fetherman F26 Cindy Worster F49 Sheri Nemeth F57 Maximillian Mosier M13 Jasmine Szabo F15 Christine Nelson F35 Min Kim F18 Misty Hildenbrand F27 Deb Hargens F62 Kristi Wade F45 Alys Brockway F48 Audrey Russell F37 Lula DeMars F11 Roger Lapthorne M58 Denise Ashford F53 Carol Finlayson F56 Keith Elliott M29 Linda Ward F59 Catherine Williams F20 Rachelle Fuller F42 Amy Hood F12 Sarah Mooney F16 Beth Brady F58 Rodney Glenn M52 Jacy Kruckenberg F39 Jeffrey Machell M53 William Kohnert M17 Stephanie Ayers F26 Judith W Warner F66 Katie Gann F19 Ginny Page F70 Jennifer Chavez F28 Catherine Trippett F54 Magali Lutz F42 Chandler -

The Foreign Service Journal, January 2004

FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy_FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy 11/10/11 12:00 PM Page C1 BAGHDAD BULLETIN I CENTURY OF THE AMERICAS? I AID PROJECTS $3.50 / JANUARY 2004 OREIGN ERVICE FJ O U R N A L STHE MAGAZINE FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS PROFESSIONALS ALPHABET SOUP U.S. Overseas Broadcasting Seeks Recipe for Success FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy_FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy 11/10/11 12:00 PM Page C2 FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy_FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy 11/10/11 12:00 PM Page 1 FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy_FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy 11/10/11 12:00 PM Page 2 FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy_FSJ C1-15 JAN 2004 copy 11/10/11 12:00 PM Page 3 CONTENTS January 2004 I Volume 81, No. 1 F OCUSON U . S . B ROADCASTING F EATURES 16 / THE ABCS OF U.S. OVERSEAS BROADCASTING LETTER FROM BAGHDAD / 49 By Steven Alan Honley An FSO recounts a memorable recent week in Baghdad. By Beth A. Payne 20 / NEW DIRECTIONS IN U.S. INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING LATIN AMERICA: BACK ON THE RADAR SCREEN? / 53 By Brian Conniff The 9/11 attacks derailed the Bush administration’s plans for a “Century of the Americas.” But now that 25 / THE VOICE OF AMERICA ENTERS A NEW ERA vision may be getting back on track. By David Jackson By George Gedda 30 / A VOICE FOR THE VOICELESS MAKING INSTITUTIONS OUT OF PROJECTS / 58 By Alex Belida Ad hoc aid projects often work very well. -

2012 RAND Annual Report

Who are you listening to? RAND CORPOraTIO ANNUN AL REPORT 2012 Our Mission The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. SANTA MONIca, WasHINGTON, PITTSBURGH, NEW ORLEANS, JACKSON, BOSTON, DOHA, CAMBRIDGE, BrUssELS, CALIFORNIA D.C. PENNSYLVANIA LOUISIANA MIssIssIPPI massacHUSETTS QATar UNITED KINGDOM BELGIUM Contents Statistics Economics Management Studies Education Operations Research Policy Analysis Physics TechnologyHealth Communications National Security Studies Medicine 4 32 34 Research and 2012 by the Staff News Analysis Numbers 36 38 42 answer be the Outreach Events Pardee RAND Graduate School 46 54 58 Investing in Advisory Boards Clients and People and Ideas Grantors Message from the Chairman and the President At the heart of RAND’s work is a belief that fact-based analysis can make individuals and communities safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. In 2012, demand for our expertise made clear that decisionmakers, thoughtleaders, and policy-minded individuals throughout the world crave our research and analysis as they look to take on the challenges before them and get ahead of those still to come. How do we know? We worked for more clients and on more projects. We received more gifts from more donors who share our commitment to public service. Media coverage of RAND analysis and people was up more than 25 percent, and published commentary bringing our research and expertise to unfolding policy debates more than doubled. The new RAND Blog, weekly Policy Currents e-newsletter, and our first iPhone app have expanded our online audience. By year’s end, our research products were downloaded more than 5.5 million times and more than 18,000 people were following RAND on Twitter.