Issue of the Newsletter [#15], Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John W. Ehrstine, William Blake's Poetical Sketches

REVIEW John W. Ehrstine, William Blake’s Poetical Sketches Michael J. Tolley Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 2, Issue 3, December 15, 1968, pp. 55-57 -55- ; ' •.' • -.' ; : >• '■ * ■ REVIEW ' --; ■- - '■ :<x .■■•■■ ■ \,' oz Bweoq n#t Wi 11iam Blake's Poetical Sketches, by John W. Ehrstine. Washington State University Press (1967), pp. DO + 108 pp. '■■■><' It is a pity that the first fulllength study of the Poetical Sketched to be published since Margaret Ruth Lowery's pioneering work of 1940 should be so little worthy the serious attention of a Blake student. Ehrstine is one of the familiar new breed of academic bookproducers, whose business is not scholarship but novel thesisweaving* Having assimilated certain ideas and critical tech niques, they apply them ruthlessly to any work that has hithertobeen fortunate enough to escape such attentions. The process is simple and: the result—that of bookproduction—is infallible. If the poor little poems protest while struggling in their Procrustean bed, one covers their noise with bland asser' 1" tions and continues to mutilate them. Eventually they satisfy one's preconcep" tions. Unfortunately, they may also impose on other people. In revewing such books one must blame mainly the publishers and their advisors; secondly the universities for their incredibly lax assessment and training of postgraduate students; thirdly the authors, who are usually dupes of their own'1 processes, for rushing into print without consult!ng the best scholars In their field. Ehrstine shows his lack of scholarship on the first two pages of his book; thereafter he has an uphill tattle!1n convincing the reader that he has some special insights Which compensate foKtfris, once fashionable, disability. -

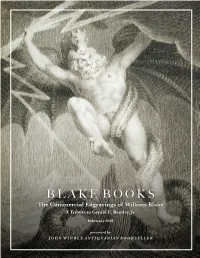

Blake Books, Contributed Immeasurably to the Understanding and Appreciation of the Enormous Range of Blake’S Works

B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 Blake is best known today for his independent vision and experimental methods, yet he made his living as a commercial illustrator. This exhibition shines a light on those commissioned illustrations and the surprising range of books in which they appeared. In them we see his extraordinary versatility as an artist but also flashes of his visionary self—flashes not always appreciated by his publishers. On display are the books themselves, objects that are far less familiar to his admirers today, but that have much to say about Blake the artist. The exhibition is a small tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. (1930 – 2017), whose scholarship, including the monumental bibliography, Blake Books, contributed immeasurably to the understanding and appreciation of the enormous range of Blake’s works. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 www.williamblakegallery.com www.johnwindle.com 415-986-5826 - 2 - B L A K E B O O K S : C O M M E R C I A L I L L U S T R A T I O N Allen, Charles. -

William Blake and His Poem “London”

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 9, pp. 1610-1614, September 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.9.1610-1614 William Blake and His Poem “London” Changjuan Zhan School of Foreign Languages, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, Shandong, China Abstract—This paper gives a detailed introduction to William Blake, a versatile poet, dramatist, artist, engraver, and publisher; and the most original romantic poet as well as painter and printmaker of the 18th century. Then his works are also introduced according to time order among which two of his collections of poems, i.e. “the songs of innocence” and “the songs of experiences” are given special attention. The features and comments on his works are introduced and demonstrated in his most famous poem “London”, from “the songs of experiences”. The paper analyzes the various technical features in this poem respectively—key image and three encounters around which the whole poem is centered; symbolism and capitalization which are used a lot in it; the choice and repetition of words which enhance the theme of the poem; and the rhyme and rhythm which give the poem a musical pattern. And then a conclusion is made that through these features, William Blake did achieve an overall impact which convey the horror and injustice that was London. Index Terms—William Blake, London, technical features, image, capitalization, repetition, rhyme and rhythm I. AN INTRODUCTION TO WILLIAM BLAKE A. William Blake’s Life William Blake was a versatile poet, dramatist, artist, engraver, and publisher. -

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake Author(s): PAUL MINER Source: Criticism, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Winter 1962), pp. 59-73 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23091046 Accessed: 20-06-2016 19:39 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Criticism This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 19:39:44 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAUL MINER* r" The TygerGenesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake There is the Cave, the Rock, the Tree, the Lake of Udan Adan, The Forest and the Marsh and the Pits of bitumen deadly, The Rocks of solid fire, the Ice valleys, the Plains Of burning sand, the rivers, cataract & Lakes of Fire, The Islands of the fiery Lakes, the Trees of Malice, Revenge And black Anxiety, and the Cities of the Salamandrine men, (But whatever is visible to the Generated Man Is a Creation of mercy & love from the Satanic Void). (Jerusalem) One of the great poetic structures of the eighteenth century is William Blake's "The Tyger," a profound experiment in form and idea. -

William Blake

THE WORKS of WILLIAM BLAKE jSptfrolu, tmir dpritical KDITEO WITH LITHOORAPIIS OF THE ILLUSTRATED “ PROPHETIC BOOKS," AND A M8 M0 IH AND INTERPRETATION EDWIN JOHN ELLIS A ttlh n r n f “Miff »ii A rcatliit,** rfr* Asn WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS Author of ** The JVnnilerinfj* nf Ohin,** " The Crwutesi Kathleen," ifr. “ Hnng nin to the te»t Ami I Lh* m&ttor will iv-wnnl, which nmdnp** Would ftumlml from M Jfauttef /.V TUJIKE VOI.S. VOL 1 LONDON BERNARD QUARITCH, 15 PICCADILLY 1893 \ A lt R ig h t* k *M*rv*ifl & 0 WILLIAM LINNELL THIS WORK IS INSCRIBED. PREFACE. The reader must not expect to find in this account of Blake's myth, or this explanation of his symbolic writings, a substitute for Blake's own works. A paraphrase is given of most of the more difficult poems, but no single thread of interpretation can fully guide the explorer through the intricate paths of a symbolism where most of the figures of speech have a two-fold meaning, and some are employed systematically in a three fold, or even a four-fold sense. " Allegory addressed to the intellectual powers while it is altogether hidden from the corporeal understanding is my definition," writes Blake, "of the most sublime poetry." Letter to Butts from Felpham, July 6th, 1803. Such allegory fills the "Prophetic Books," yet it is not so hiddon from the corporeal understanding as its author supposed. An explanation, continuous throughout, if not complete for side issues, may be obtained from the enigma itself by the aid of ordinary industry. -

Dissertations on William Blake

ARTICLE “The Eternal Wheels of Intellect”: Dissertations on William Blake G. E. Bentley, Jr. Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue 4, Spring 1979, pp. 224-243 224 "THE ETERNAL WHEELS OF INTELLECT": DISSERTATIONS ON WILLIAM BLAKE G. E. BENTLEY. JR. illiam Blake has been the subject of doctoral seems likely that there were more dissertations on Wdissertations for over sixty years, and a Blake written in Germany and Japan than are recorded sufficient number have been completed and here. accepted—over two hundred—to make it possible to draw some interesting conclusions about patterns of The national distribution of the universities interest in William Blake and about patterns in higher at which the degrees were awarded is striking: education. In general, the conclusions which these Canada 14 (mostly from Toronto), England 24 (mostly facts make possible, at least to me, confirm what Oxford, Cambridge, and London), Finland 1, France 3 one might have guessed but supply the facts to Germany 4, India 3, Ireland 1, Japan 2, New Zealand' justify one's guesses. 1, Scotland 1, Switzerland 4, the United States 204. I have no record of Blake doctoral dissertations Before one places much weight upon either the in Australia, Italy, or South Africa. About 96% facts or the conclusions based upon them, however, are from the English-speaking world,14 which is not one must recognize the fragmentary nature of our surprising, and about 77% are from the United States evidence and whence it comes. About 60% of those which I suppose is not really surprising either, theses of which I have records are listed in considering that there must be about as many Ph.D. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeob Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I 73-26,873

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on die film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} the Visionary Company

THE VISIONARY COMPANY: READING OF ENGLISH ROMANTIC HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Prof. Harold Bloom | 506 pages | 01 Jun 1971 | Cornell University Press | 9780801491177 | English | Ithaca, United States The Visionary Company: Reading of English Romantic History PDF Book Of the completion of that stupendous Conquest which began at Hastings, and which changed the civilization of a whole nation, this is not the place to speak. Collins saw himself as a poet separated by the school of Waller from a main tradition of the Enghsh Renaissance, the creation of a British mythology: the Faery Land of Spenser, the green world of Shakespeare's romances, the Biblical and prophetic self-identification of Milton. Novelists of the Victorian Age. So in the matter of glory or honor; it was, apparently, not the love of fighting, but rather the love of honor resulting from fighting well, which animated our forefathers in every campaign. In the Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Leutha was only a spirit of potential sexuality. Though much has been written about both these two, this is the first modern biography to consider them together. That Nature is largely responsible for the cruel deceptions of Experience becomes clearer as one reads through the cycle of songs. The curious irony is that Blake, so masterful in playing upon our quasi-imaginative self-indulgings, is so frequently and wrongly accused of loving himself in his own. O Immortal! This is even more true of its songs than of its painting and sculpture; though permanence is a quality we should hardly expect in the present deluge of books and magazines pouring day and night from our presses in the name of literature. -

Poetical Sketches

POETICAL SKETCHES William Blake POETICAL SKETCHES Table of Contents POETICAL SKETCHES.........................................................................................................................................1 William Blake................................................................................................................................................1 To Spring........................................................................................................................................................1 To Summer.....................................................................................................................................................2 To Autumn.....................................................................................................................................................2 To Winter.......................................................................................................................................................3 To the Evening Star........................................................................................................................................3 To Morning....................................................................................................................................................3 Fair Elenor......................................................................................................................................................4 Song...............................................................................................................................................................6 -

Imagination and Emotion in William Blake's Poems

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, January 2016, Vol. 6, No. 1, 17-22 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.01.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Imagination and Emotion in William Blake’s Poems XU Jian-gang, HUANG Rong, WANG Dong-qing China Three Gorges University, Yichang, China Writer’s imagination does not only provide inspiration for literary creation, but also contribute literature works with more dazzling brilliance. As a representative of the British Romantic Poetry—William Blake, whose poems are full of imagination, always concedes his emotion and thoughts in a variety of imageries, exposing the reality of his times within his poetry writing. However, William Blake’s imagination is no castles in the air, but based on the religious mythology, historical background, and the poet’s life experience and dream pursuit. Only with in-depth understanding of the imagination in William Blake’s poems can those hidden emotions and thoughts be grasped and appreciated. Keywords: imagination, emotion, William Blake Introduction Britain at the end of 18th century was mainly under the control of three powers: monarch, religion, and bourgeois, which results in the middle and lower classes dominated under misery and impoverishment. Facing this tragic reality, William Blake, concealing his emotion in the words and imagination, minutely recorded the dark times in his poems. Sunflower Is Weary of Time, but Counts Steps of the Sun William Blake’s early poems are likely to show great respect towards Christ and church. In the collection The Song of Innocence, most of William’s imaginative writings are created on the basis of religious mythology. -

William Blake, Poet, Painter, and Artist-Printmaker an Interview with Michael Phillips

William Blake, Poet, Painter, and Artist-Printmaker An Interview with Michael Phillips Conducted April 2012 By Enéias Farias Tavares Michael, I would like to begin this interview by asking how you first became interested in William Blake, your first contact with Blake’s illuminated books, and what influenced your approach to his work as a poet, painter and as an artist-printmaker? Looking back I can see how certain experiences may have been Formative, or at least encouraged interests that were instinctive. But beFore doing so, it may be helpful iF I clariFy very brieFly what my approach to Blake has been and remains. Increasingly over the years my interests have been in how Blake created his works, that is to say, how his poems evolved in manuscript and the social and historical circumstances that influenced their creation. This led me to try to learn how he then went on to reproduce and publish his works himselF, by means of a very simple but highly innovative method of printmaking. I have not, For example, been interested in bringing a method of interpretation to Blake’s work From outside, For example, an archetypal, psychoanalytical, Feminist, or deconstructive approach. In contrast, my approach has been empirical, in attempting to reconstruct the immediate circumstances of Blake’s liFe and work From historical evidence, and in particular how and why his works were made and reproduced. Recovering how he reproduced his works has very much entailed a hands-on approach, working and experimenting in the studio using the methods and materials that Blake himselF used. -

ABOUT the POET and HIS POETRY William Blake

ABOUT THE POET AND HIS POETRY William Blake William Blake was born in London on November 28, 1757, to James, a hosier, and Catherine Blake. Two of his six siblings died in infancy. From early childhood, Blake spoke of having visions—at four he saw God ―put his head to the window‖; around age nine, while walking dathrough the countryside, he saw a tree filled with angels. Although his parents tried to discourage him from ―lying," they did observe that he was different from his peers and did not force him to attend conventional school. He learned to read and write at home. At age ten, Blake expressed a wish to become a painter, so his parents sent him to drawing school. Two years later, Blake began writing poetry. When he turned fourteen, he apprenticed with an engraver because art school proved too costly. One of Blake‘s assignments as apprentice was to sketch the tombs at Westminster Abbey, exposing him to a variety of Gothic styles from which he would draw inspiration throughout his career. After his seven-year term ended, he studied briefly at the Royal Academy. In 1782, he married an illiterate woman named Catherine Boucher. Blake taught her to read and to write, and also instructed her in draftsmanship. Later, she helped him print the illuminated poetry for which he is remembered today; the couple had no children. In 1784 he set up a printshop with a friend and former fellow apprentice, James Parker, but this venture failed after several years. For the remainder of his life, Blake made a meager living as an engraver and illustrator for books and magazines.