William Blake, Poet, Painter, and Artist-Printmaker an Interview with Michael Phillips

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 2013

ARTICLE Part II: Reproductions of Drawings and Paintings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors Section B: Collections and Selections Part III: Commercial Engravings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors William Blake and His Circle: Part IV: Catalogues and Bibliographies A Checklist of Publications and Section A: Individual Catalogues Section B: Collections and Selections Discoveries in 2013 Part V: Books Owned by William Blake the Poet Part VI: Criticism, Biography, and Scholarly Studies By G. E. Bentley, Jr. Division II: Blake’s Circle Blake Publications and Discoveries in 2013 with the assistance of Hikari Sato for Japanese publications and of Fernando 1 The checklist of Blake publications recorded in 2013 in- Castanedo for Spanish publications cludes works in French, German, Japanese, Russian, Span- ish, and Ukrainian, and there are doctoral dissertations G. E. Bentley, Jr. ([email protected]) is try- from Birmingham, Cambridge, City University of New ing to learn how to recognize the many styles of hand- York, Florida State, Hiroshima, Maryland, Northwestern, writing of a professional calligrapher like Blake, who Oxford, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Voronezh used four distinct hands in The Four Zoas. State, and Wrocław. The Folio Society facsimile of Blake’s designs for Gray’s Poems and the detailed records of “Sale Editors’ notes: Catalogues of Blake’s Works 1791-2013” are likely to prove The invaluable Bentley checklist has grown to the point to be among the most lastingly valuable of the works listed. where we are unable to publish it in its entirety. All the material will be incorporated into the cumulative Gallica “William Blake and His Circle” and “Sale Catalogues of William Blake’s Works” on the Bentley Blake Collection 2 A wonderful resource new to me is Gallica <http://gallica. -

John W. Ehrstine, William Blake's Poetical Sketches

REVIEW John W. Ehrstine, William Blake’s Poetical Sketches Michael J. Tolley Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 2, Issue 3, December 15, 1968, pp. 55-57 -55- ; ' •.' • -.' ; : >• '■ * ■ REVIEW ' --; ■- - '■ :<x .■■•■■ ■ \,' oz Bweoq n#t Wi 11iam Blake's Poetical Sketches, by John W. Ehrstine. Washington State University Press (1967), pp. DO + 108 pp. '■■■><' It is a pity that the first fulllength study of the Poetical Sketched to be published since Margaret Ruth Lowery's pioneering work of 1940 should be so little worthy the serious attention of a Blake student. Ehrstine is one of the familiar new breed of academic bookproducers, whose business is not scholarship but novel thesisweaving* Having assimilated certain ideas and critical tech niques, they apply them ruthlessly to any work that has hithertobeen fortunate enough to escape such attentions. The process is simple and: the result—that of bookproduction—is infallible. If the poor little poems protest while struggling in their Procrustean bed, one covers their noise with bland asser' 1" tions and continues to mutilate them. Eventually they satisfy one's preconcep" tions. Unfortunately, they may also impose on other people. In revewing such books one must blame mainly the publishers and their advisors; secondly the universities for their incredibly lax assessment and training of postgraduate students; thirdly the authors, who are usually dupes of their own'1 processes, for rushing into print without consult!ng the best scholars In their field. Ehrstine shows his lack of scholarship on the first two pages of his book; thereafter he has an uphill tattle!1n convincing the reader that he has some special insights Which compensate foKtfris, once fashionable, disability. -

Alicia Ostriker, Ed., William Blake: the Complete Poems

REVIEW Alicia Ostriker, ed., William Blake: The Complete Poems John Kilgore Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue 4, Spring 1979, pp. 268-270 268 psychological—carried by Turner's sublimely because I find myself in partial disagreement with overwhelming sun/god/king/father. And Paulson argues Arnheim's contention "that any organized entity, in that the vortex structure within which this sun order to be grasped as a whole by the mind, must be characteristically appears grows as much out of translated into the synoptic condition of space." verbal signs and ideas ("turner"'s name, his barber- Arnheim seems to believe, not only that all memory father's whorled pole) as out of Turner's early images of temporal experiences are spatial, but that sketches of vortically copulating bodies. Paulson's they are also synoptic, i.e. instantaneously psychoanalytical speculations are carried to an perceptible as a comprehensive whole. I would like extreme by R. F. Storch who argues, somewhat to suggest instead that all spatial images, however simplistically, that Shelley's and Turner's static and complete as objects, are experienced tendencies to abstraction can be equated with an temporally by the human mind. In other works, we alternation between aggression toward women and a "read" a painting or piece of sculpture or building dream-fantasy of total love. Storch then applauds in much the same way as we read a page. After Constable's and Wordsworth's "sobriety" at the isolating the object to be read, we begin at the expense of Shelley's and Turner's overly upper left, move our eyes across and down the object; dissociated object-relations, a position that many when this scanning process is complete, we return to will find controversial. -

The Bravery of William Blake

ARTICLE The Bravery of William Blake David V. Erdman Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 10, Issue 1, Summer 1976, pp. 27-31 27 DAVID V. ERDMAN The Bravery of William Blake William Blake was born in the middle of London By the time Blake was eighteen he had been eighteen years before the American Revolution. an engraver's apprentice for three years and had Precociously imaginative and an omnivorous reader, been assigned by his master, James Basire, to he was sent to no school but a school of drawing, assist in illustrating an antiquarian book of at ten. At fourteen he was apprenticed as an Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain. Basire engraver. He had already begun writing the sent Blake into churches and churchyards but exquisite lyrics of Poetioal Sketches (privately especially among the tombs in Westminster Abbey printed in 1783), and it is evident that he had to draw careful copies of the brazen effigies of filled his mind and his mind's eye with the poetry kings and queens, warriors and bishops. From the and art of the Renaissance. Collecting prints of drawings line engravings were made under the the famous painters of the Continent, he was happy supervision of and doubtless with finishing later to say that "from Earliest Childhood" he had touches by Basire, who signed them. Blake's dwelt among the great spiritual artists: "I Saw & longing to make his own original inventions Knew immediately the difference between Rafael and (designs) and to have entire charge of their Rubens." etching and engraving was yery strong when it emerged in his adult years. -

William Blake 1 William Blake

William Blake 1 William Blake William Blake William Blake in a portrait by Thomas Phillips (1807) Born 28 November 1757 London, England Died 12 August 1827 (aged 69) London, England Occupation Poet, painter, printmaker Genres Visionary, poetry Literary Romanticism movement Notable work(s) Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Four Zoas, Jerusalem, Milton a Poem, And did those feet in ancient time Spouse(s) Catherine Blake (1782–1827) Signature William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[1] His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[2] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3] Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham[4] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[5] or "Human existence itself".[6] Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings William Blake 2 and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic",[7] for its large appearance in the 18th century. -

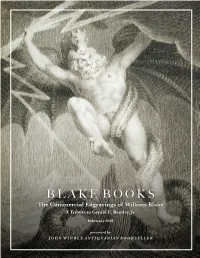

Blake Books, Contributed Immeasurably to the Understanding and Appreciation of the Enormous Range of Blake’S Works

B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 Blake is best known today for his independent vision and experimental methods, yet he made his living as a commercial illustrator. This exhibition shines a light on those commissioned illustrations and the surprising range of books in which they appeared. In them we see his extraordinary versatility as an artist but also flashes of his visionary self—flashes not always appreciated by his publishers. On display are the books themselves, objects that are far less familiar to his admirers today, but that have much to say about Blake the artist. The exhibition is a small tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. (1930 – 2017), whose scholarship, including the monumental bibliography, Blake Books, contributed immeasurably to the understanding and appreciation of the enormous range of Blake’s works. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 www.williamblakegallery.com www.johnwindle.com 415-986-5826 - 2 - B L A K E B O O K S : C O M M E R C I A L I L L U S T R A T I O N Allen, Charles. -

And Edward Young's Book Of

MINUTE PARTICULAR Blake’s “The Tyger” and Edward Young’s Book of Job Robert F. Gleckner Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 21, Issue 3, Winter 1987/1988, pp. 99-101 WINTER 1987-88 BLAKE/AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY PAGE 99 Blake's "The Tyger" and Edward Youngs burden of God's angry reproof ofJob is the reaffirming of the latter's littleness and incapacity, culminating in Book of Job the advice to "abase" the proud "and bring him low. " 3 In any discussion of Blake's speaker, then, Young's foot- Robert F. Gleckner note is at least an intriguing gloss on the biblical pas- sage. If sublime interrogation is a manifestation of "majesty incensed, " then the speaker of' 'The Tyger, " in Of all of Blake's shorter poems "The Tyger" has received, his usurpation of this rhetorical mode, is presumptuous by far, the most attention, an often confusing array of beyond words, asking "the guilty a proper question" so complementary (as well as contradictory) interpreta- that the guilty will, "in effect, pass sentence on him- tions, source studies, and prosodic analyses. Of those, self." On the other hand, Blake may have found in the seeking hither and yon for tigers of various sorts has Youn~'s idea of "bidding a person execute himself" the produced especially little that is illuminating about germ1nal principle of the structure of "The Tyger," in Blake's possible sources for the poem as distinct from which Blake, as creator, quite literally allows his speaker, sources for his choice of animal or for its (still uneasily by questioning, to convict himself before the reader's received) portrait in the illustration. -

David Punter, Ed., William Blake: Selected Poetry and Prose

REVIEW Stanley Kunitz, ed., The Essential Blake; Michael Mason, ed., William Blake; David Punter, ed., William Blake: Selected Poetry and Prose E. B. Murray Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 24, Issue 4, Spring 1991, pp. 145-153 Spring 1991 BLAKE/AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY Not so the Oxford Authors and Rout- As we know, and contrary to Mason's ledge Blakes. They do have some pre- implications, Blake felt his illumina- REVIEWS tensions and they may not be tions an integral part of his composite altogether harmless. Michael Mason is art, going so far as to applaud himself initially concerned with telling us what (in the third person) for having in- he does not do in his edition. He does vented "a method of Printing which Stanley Kunitz, ed. The Es not include An Island in the Moon, The combines the Painter and Poet" and, in sential Blake. New York: Book of Ahania, or The FourZoas. He an earlier self-evaluation, he bluntly The Ecco Press, 1987. 92 does not follow a chronological order asserts, through a persona, that those pp. $5.00 paper; Michael in presenting Blake's texts; he does not (pace Mason) who will not accept and Mason, ed. William Blake. provide deleted or alternative read- pay highly for the illuminated writings ings; he does not provide the illumina- he projected "will be ignorant fools Oxford: Oxford University tions or describe them; he does not and will not deserve to live." Ipse dixit. Press, 1988. xxvi + 601 pp. summarize the content of Blake's works The poet/artist is typically seconded $45.00 cloth/$15.95 paper; nor does he explicate Blake's mythol- by his twentieth-century editors, who, David Punter, ed. -

William Blake and His Poem “London”

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 9, pp. 1610-1614, September 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.9.1610-1614 William Blake and His Poem “London” Changjuan Zhan School of Foreign Languages, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, Shandong, China Abstract—This paper gives a detailed introduction to William Blake, a versatile poet, dramatist, artist, engraver, and publisher; and the most original romantic poet as well as painter and printmaker of the 18th century. Then his works are also introduced according to time order among which two of his collections of poems, i.e. “the songs of innocence” and “the songs of experiences” are given special attention. The features and comments on his works are introduced and demonstrated in his most famous poem “London”, from “the songs of experiences”. The paper analyzes the various technical features in this poem respectively—key image and three encounters around which the whole poem is centered; symbolism and capitalization which are used a lot in it; the choice and repetition of words which enhance the theme of the poem; and the rhyme and rhythm which give the poem a musical pattern. And then a conclusion is made that through these features, William Blake did achieve an overall impact which convey the horror and injustice that was London. Index Terms—William Blake, London, technical features, image, capitalization, repetition, rhyme and rhythm I. AN INTRODUCTION TO WILLIAM BLAKE A. William Blake’s Life William Blake was a versatile poet, dramatist, artist, engraver, and publisher. -

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake

"The Tyger": Genesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake Author(s): PAUL MINER Source: Criticism, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Winter 1962), pp. 59-73 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23091046 Accessed: 20-06-2016 19:39 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Criticism This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Mon, 20 Jun 2016 19:39:44 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAUL MINER* r" The TygerGenesis & Evolution in the Poetry of William Blake There is the Cave, the Rock, the Tree, the Lake of Udan Adan, The Forest and the Marsh and the Pits of bitumen deadly, The Rocks of solid fire, the Ice valleys, the Plains Of burning sand, the rivers, cataract & Lakes of Fire, The Islands of the fiery Lakes, the Trees of Malice, Revenge And black Anxiety, and the Cities of the Salamandrine men, (But whatever is visible to the Generated Man Is a Creation of mercy & love from the Satanic Void). (Jerusalem) One of the great poetic structures of the eighteenth century is William Blake's "The Tyger," a profound experiment in form and idea. -

William Blake

THE WORKS of WILLIAM BLAKE jSptfrolu, tmir dpritical KDITEO WITH LITHOORAPIIS OF THE ILLUSTRATED “ PROPHETIC BOOKS," AND A M8 M0 IH AND INTERPRETATION EDWIN JOHN ELLIS A ttlh n r n f “Miff »ii A rcatliit,** rfr* Asn WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS Author of ** The JVnnilerinfj* nf Ohin,** " The Crwutesi Kathleen," ifr. “ Hnng nin to the te»t Ami I Lh* m&ttor will iv-wnnl, which nmdnp** Would ftumlml from M Jfauttef /.V TUJIKE VOI.S. VOL 1 LONDON BERNARD QUARITCH, 15 PICCADILLY 1893 \ A lt R ig h t* k *M*rv*ifl & 0 WILLIAM LINNELL THIS WORK IS INSCRIBED. PREFACE. The reader must not expect to find in this account of Blake's myth, or this explanation of his symbolic writings, a substitute for Blake's own works. A paraphrase is given of most of the more difficult poems, but no single thread of interpretation can fully guide the explorer through the intricate paths of a symbolism where most of the figures of speech have a two-fold meaning, and some are employed systematically in a three fold, or even a four-fold sense. " Allegory addressed to the intellectual powers while it is altogether hidden from the corporeal understanding is my definition," writes Blake, "of the most sublime poetry." Letter to Butts from Felpham, July 6th, 1803. Such allegory fills the "Prophetic Books," yet it is not so hiddon from the corporeal understanding as its author supposed. An explanation, continuous throughout, if not complete for side issues, may be obtained from the enigma itself by the aid of ordinary industry. -

Dissertations on William Blake

ARTICLE “The Eternal Wheels of Intellect”: Dissertations on William Blake G. E. Bentley, Jr. Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue 4, Spring 1979, pp. 224-243 224 "THE ETERNAL WHEELS OF INTELLECT": DISSERTATIONS ON WILLIAM BLAKE G. E. BENTLEY. JR. illiam Blake has been the subject of doctoral seems likely that there were more dissertations on Wdissertations for over sixty years, and a Blake written in Germany and Japan than are recorded sufficient number have been completed and here. accepted—over two hundred—to make it possible to draw some interesting conclusions about patterns of The national distribution of the universities interest in William Blake and about patterns in higher at which the degrees were awarded is striking: education. In general, the conclusions which these Canada 14 (mostly from Toronto), England 24 (mostly facts make possible, at least to me, confirm what Oxford, Cambridge, and London), Finland 1, France 3 one might have guessed but supply the facts to Germany 4, India 3, Ireland 1, Japan 2, New Zealand' justify one's guesses. 1, Scotland 1, Switzerland 4, the United States 204. I have no record of Blake doctoral dissertations Before one places much weight upon either the in Australia, Italy, or South Africa. About 96% facts or the conclusions based upon them, however, are from the English-speaking world,14 which is not one must recognize the fragmentary nature of our surprising, and about 77% are from the United States evidence and whence it comes. About 60% of those which I suppose is not really surprising either, theses of which I have records are listed in considering that there must be about as many Ph.D.